-

Články

- Časopisy

- Kurzy

- Témy

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Parent-of-Origin Effects of the Gene on Adiposity in Young Adults

To date, genetic variants identified in large-scale genetic studies using recent technical and methodological advances explain only a small proportion of the genetic basis of obesity, diabetes and other cardiovascular risk factors. These studies were typically conducted in samples of unrelated individuals. Here we utilize a family-based approach to identify genetic variants associated with obesity-related traits. Specifically, we examined the separate contribution of maternally - vs. paternally-inherited common genetic variants to these traits. By examining 1250 young adults and their mothers from Jerusalem, we show that a specific genetic variant, rs1367117, located in the APOB gene on chromosome 2 is related to body mass index and waist circumference when inherited from mother and not from father. This maternal effect is not restricted to Jerusalemites, but is also seen in a large sample of individuals of European descent from independent family studies worldwide. Our findings provide support of the role of complex genetic mechanisms in obesity, and highlight the benefit of utilizing family studies for uncovering genetic pathways underlying common risk factors and diseases.

Published in the journal: Parent-of-Origin Effects of the Gene on Adiposity in Young Adults. PLoS Genet 11(10): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1005573

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1005573Summary

To date, genetic variants identified in large-scale genetic studies using recent technical and methodological advances explain only a small proportion of the genetic basis of obesity, diabetes and other cardiovascular risk factors. These studies were typically conducted in samples of unrelated individuals. Here we utilize a family-based approach to identify genetic variants associated with obesity-related traits. Specifically, we examined the separate contribution of maternally - vs. paternally-inherited common genetic variants to these traits. By examining 1250 young adults and their mothers from Jerusalem, we show that a specific genetic variant, rs1367117, located in the APOB gene on chromosome 2 is related to body mass index and waist circumference when inherited from mother and not from father. This maternal effect is not restricted to Jerusalemites, but is also seen in a large sample of individuals of European descent from independent family studies worldwide. Our findings provide support of the role of complex genetic mechanisms in obesity, and highlight the benefit of utilizing family studies for uncovering genetic pathways underlying common risk factors and diseases.

Introduction

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified multiple loci associated with cardio-metabolic risk (CMR) phenotypes and traits, such as adiposity and glycemic traits (e.g [1–4]). GWAS are conducted, very largely, in unrelated individuals. In general, the magnitudes of these genetic associations are small to modest, and the loci account for only a small proportion of the heritability of these traits [5–8]. To explain the “missing” heritability, various research strategies for follow-up studies have been proposed, including focusing on gene-environment interactions, on rare variants with moderate effects and on parent-of-origin effects (POEs) [7, 9].

POEs are non-Mendelian transmittable genetic effects on phenotypes, where the phenotype in offspring depends on whether transmission originated from the mother or father. In mammals, POEs can be caused by genomic imprinting, maternal genetic effects on the intrauterine environment, or maternally inherited mitochondrial genes [10]. The most obvious mechanism underlying POEs is genomic imprinting; imprinted genes show parental-specific monoallelic or partial expression, dictated by the parental origin of the chromosome [11, 12].

In the past decade, linkage studies have demonstrated POEs on both binary and continuous CMR outcomes [13–17]. Yet, despite evidence for POEs from linkage studies, most association studies have overlooked their potential influence on CMR traits, and the extent and magnitude of POEs on CMR traits remain largely unknown. One important exception, from Iceland, demonstrated that inclusion of the parental source of alleles significantly strengthened previously-reported associations with type 2 diabetes [18]. Two subsequent studies in Icelanders detected POEs on age at menarche and thyroid-stimulating hormone levels, traits that are associated with CMR [19, 20].

To examine POEs on adiposity and glycemic traits in young adults, we leveraged existing genotype data and CMR trait measurements on mother-offspring pairs from a longitudinal study nested within a historical birth cohort, together with GWAS and bioinformatics databases. We replicated our findings using extended pedigrees from three family studies. Our hypothesis was that, in genes where variants are known to be associated with CMR traits, knowledge of the parental source of genetic variants would reveal POEs on body mass index (BMI), waist circumference (WC), and fasting glucose and insulin levels.

Results

Distribution of JPS offspring adiposity and glycemic traits at mean age 32 and characteristics of the 18 genes and 182 tag SNPs selected for this analysis in JPS are presented in the S1–S4 Tables. All SNPs were common (minor allele frequency (MAF)>0.06) and not far from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (p>10−5). Associations between offspring genotypes, with and without considering parental source of alleles, for the 182 SNPs and the four traits BMI, WC, fasting glucose and fasting insulin are presented in S5 Table. Nominally significant POEs for adiposity and glycemic traits were observed in JPS. Consequently, 30 of the 182 SNPs initially tested for POE in the JPS were moved forward for replication in the 3 other family studies (S6 Table). In the joint analysis of results from JPS, FHS, FamHS and ERF, significant POEs were observed for a variant in the APOB gene (Table 1).

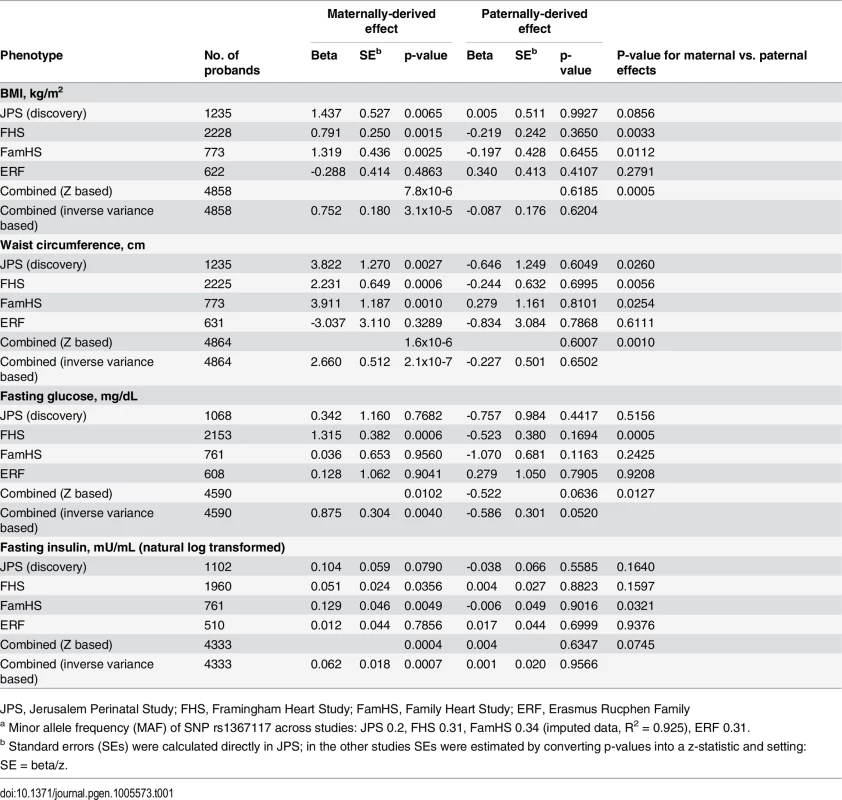

Tab. 1. Parent-of-origin effects of APOB SNP rs1367117a on adiposity and glycemic traits.

JPS, Jerusalem Perinatal Study; FHS, Framingham Heart Study; FamHS, Family Heart Study; ERF, Erasmus Rucphen Family Adiposity and glycemic traits

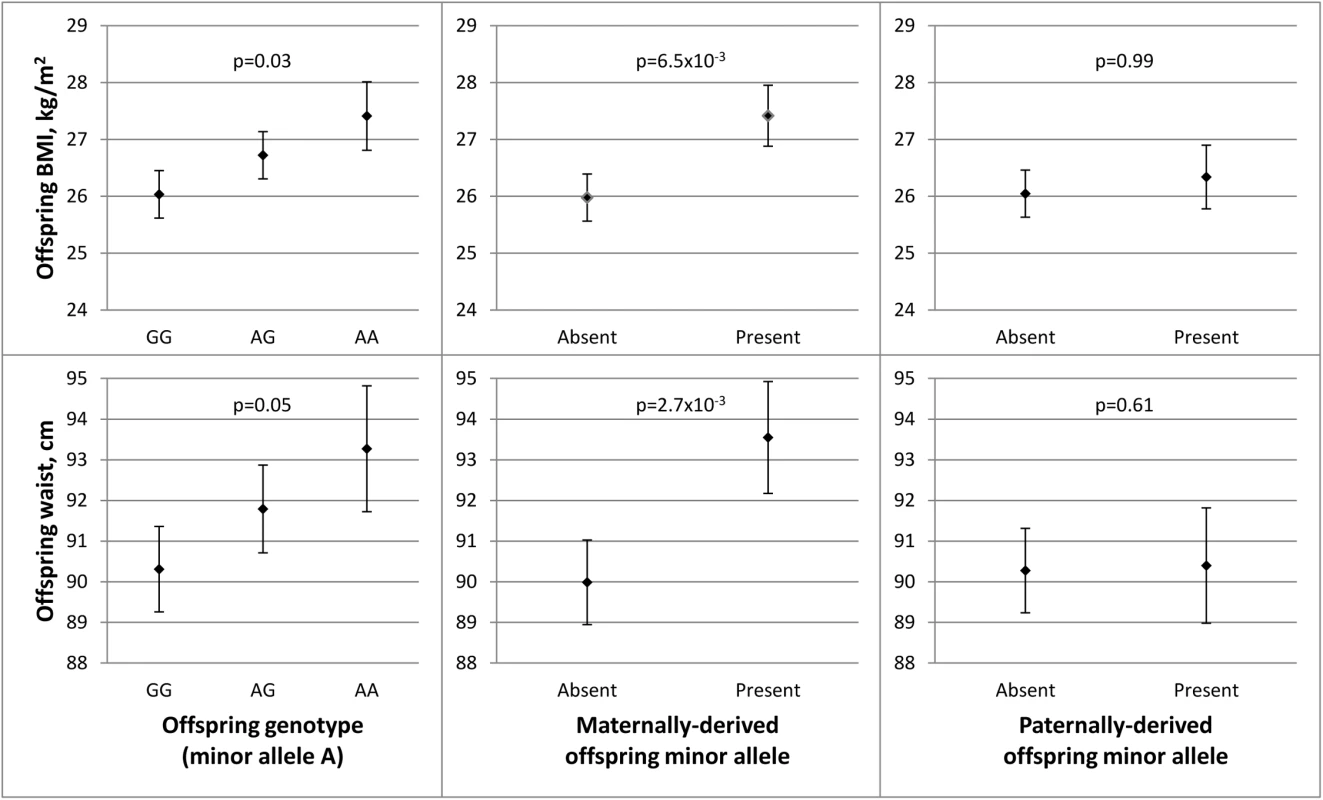

In the discovery stage conducted in JPS, SNP rs1367117, a coding SNP located within the APOB gene, demonstrated significant POEs on adiposity traits (Table 1 and S5 Table). Specifically, significant associations were demonstrated when the minor allele was inherited from the mother for offspring BMI (beta = 1.44, p-value = 6.5x10-3) and WC (beta = 3.82, p-value = 2.7x10-3). The corresponding paternally-derived effects were non-significant (p>0.6). As expected in the setting of POEs, in JPS associations seen with the maternally-derived minor allele were approximately twice as strong as those that did not consider the parental source of the allele (effects sizes were 0.7 (p-value = .03) and 1.5 (p-value = .05) for BMI and WC respectively) (Fig 1 and S5 Table). In fact, the differences in simple heritability estimates in JPS derived from mother-offspring correlations [21, 22] based on models with either adjustment for POE or additive genetic effects of the APOB variant suggested that POE of the APOB SNP explains roughly 0.30% and 0.58% of BMI and WC heritability, respectively. No changes in heritability estimates for BMI or WC were observed for the additive genetic effect of this variant.

Fig. 1. Parent-of-origin effects of APOB SNP rs1367117 on adiposity traits in JPS.

This figure illustrates the associations between APOB SNP rs1367117 and offspring BMI (top panel) and waist circumference (WC) (bottom panel). Adjusted means and standard errors (represented by error bars) for BMI and WC by genotype were determined using estimates from linear regression models adjusted for ethnicity and gender. Comparing offspring genotype effect (left panel), maternally-derived effect (middle panel) and paternally-derived effect (right panel) reveals a strengthened and more significant maternal-specific association with both traits. We also conducted sensitivity analyses in which we excluded heterozygous mother-offspring pairs (191 of 1235 pairs) instead of using probability-based estimated dosage in these pairs. These analyses resulted in similar or larger estimates for APOB rs1367117 POE on BMI (maternal beta = 1.46; p = .048), WC (maternal beta = 5.26; p = .003) and fasting insulin (natural log transformed, maternal beta = .212; p = .004) compared to those using estimated dosage (Table 1) suggesting that our probability-based estimated dosage approach is likely conservative. Additionally, we used simulations to assess the likelihood of false positive findings. Permutation-based p-values for the maternal effect on BMI (p-value = .0079) and on WC (p-value = .0048) were very close to the observed maternal p-values (p-value = .0065 and .0027 for BMI and WC, respectively). Detailed information on simulations in JPS (and in FHS) can be found in S1 Text (permutation testing).

Testing for POEs for APOB SNP rs1367117 in the replication and meta-analysis stage, also showed a significant maternally-derived effect in FHS and FamHS separately, but not in ERF, and in all four studies combined on both BMI (combined beta = 0.75, p-value = 3.1x10-5) and WC (combined beta = 2.66, p-value = 2.1x10-7) (Table 1). The effect sizes for the maternal-specific associations in JPS and FamHS were essentially identical, whereas the corresponding effects in FHS were somewhat smaller. The associations of the paternally-derived allele with those traits were not significant (F-test p-values for difference between maternally - and paternally-derived effects were 5.0x10-4 and 1.0x10-3 for BMI and WC respectively).

Maternally-derived associations of this APOB SNP with borderline significance were also seen with fasting glucose and insulin levels in the combined results (combined p-value = 4.0x10-3 and 7.4x10-4 for glucose and insulin respectively), whereas no associations were observed with the paternally-derived allele (Table 1).

Lipids, lipoproteins and blood pressure traits

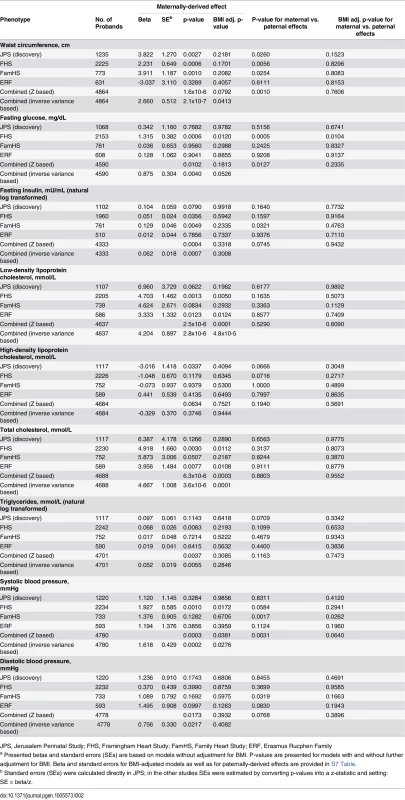

Because APOB is a major component of lipoprotein particles and an important contributor to the atherosclerotic process [23, 24], we examined whether there is also evidence for POEs of APOB rs1367117 on other CMR traits, including LDL-C, HDL-C, total cholesterol (TC), triglycerides (TG) and systolic and diastolic BP (S7 Table). A maternally-derived association, and not paternally-derived, was observed for SBP in the combined analysis (combined beta = 1.62, p-value = 1.6x10-4; F-test p-value for difference = 3.1x10-3). Significant maternal and paternal associations, of similar magnitudes, were shown with both LDL-C (maternal beta = 4.20, p-value = 2.8x10-6; paternal beta = 3.54, p-value = 5.0x10-5) and TC (maternal beta = 4.67, p-value = 3.6x10-6; paternal beta = 3.67, p-value = 1.7x10-4) (F-test p-values for difference between maternal and paternal effects were non-significant), reflecting offspring genotype effect, irrespective of the parental source (additive genetic effect is discussed below).

Mediating role of BMI

To further explore the observed parental-specific associations of APOB with CMR traits, we examined the influence of offspring BMI on these associations. Further adjustment for BMI resulted in attenuation of the observed maternally-derived effects of APOB rs1367117 on waist, SBP, glucose and insulin to the null (Table 2). In contrast, adjustment for BMI had minimal effect on the maternal and paternal associations with both LDL-C and TC (S7 Table).

Tab. 2. Maternally-derived effects of APOB SNP rs1367117 on cardio-metabolic traits with and without adjustment for BMIa.

JPS, Jerusalem Perinatal Study; FHS, Framingham Heart Study; FamHS, Family Heart Study; ERF, Erasmus Rucphen Family Additive genetic effect on cardio-metabolic traits

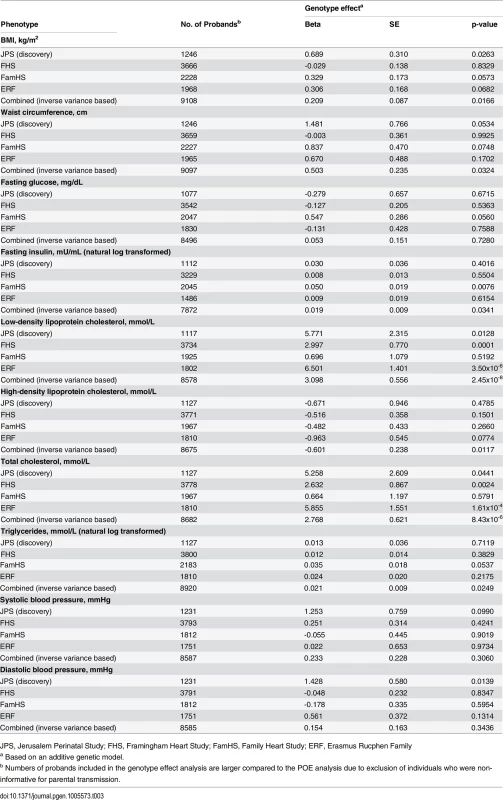

We have additionally examined the associations of offspring APOB rs1367117 with cardio-metabolic traits, overlooking the parental source of the minor allele, in the four studies separately and combined (Table 3). The combined data pointed to a substantial additive genotype effect on lipid traits, mainly on LDL-C and TC, which is in agreement with the aforementioned POE results showing both maternal and paternal effects on LDL-C and TC (S7 Table). On the other hand, genotype effects on adiposity traits (BMI and WC) were relatively minor both in size and significance, emphasizing the maternal-specific nature of the APOB rs1367117-adiposity association.

Tab. 3. Genotype effect of APOB SNP rs1367117 on cardio-metabolic traits.

JPS, Jerusalem Perinatal Study; FHS, Framingham Heart Study; FamHS, Family Heart Study; ERF, Erasmus Rucphen Family Fine-mapping the APOB parent-of-origin effect on BMI

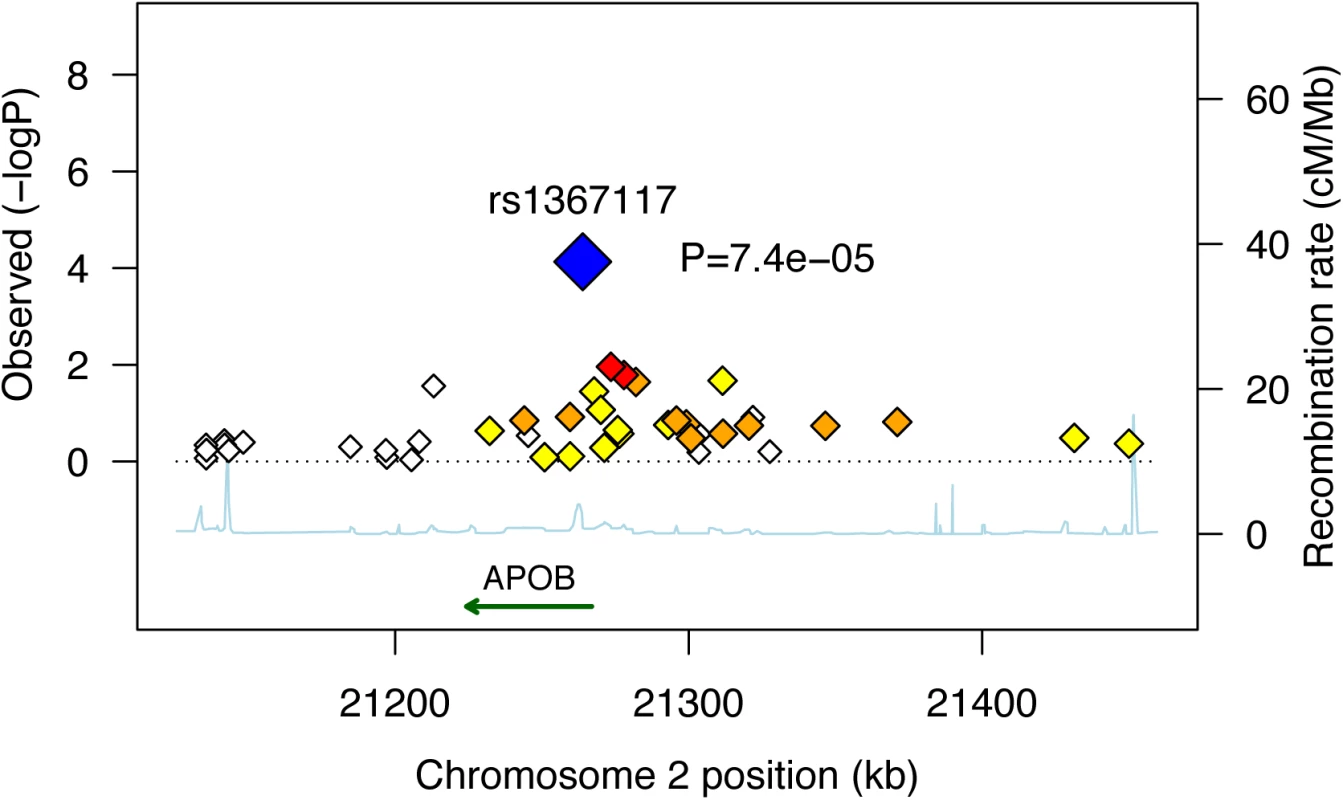

In an attempt to fine-map the POE observed for APOB rs1367117 on adiposity, we used HapMap tagger [25] and SNAP Proxy Search function [26] to select SNPs that either tag the APOB gene region (i.e. tag SNPs using r2 thershold≥0.8 within the interval spanning the gene itself and 100kb on each side) or that are in moderate linkage disequilibrium (LD) with the SNP of interest (i.e. r2 values between 0.4–0.7). Forty two SNPs were identified and we then examined POEs of these selected SNPs on BMI in the 3 studies where genome-wide data was available (i.e. FHS, FamHS and ERF) and meta-analyzed the results (S8 and S9 Tables). To illustrate the results, we used a regional plot developed by Saxena et al. [27] (Fig 2). The plot presents the combined p-values of the maternally-derived effects on BMI, showing rather higher significance for the SNPs that are in higher LD with APOB rs1367117. As expected, the degree of significance of the maternal-specific associations dropped with the decrease in LD and increase in distance from the SNP of interest.

Fig. 2. Combined* maternally-derived effects of SNPs spanning the APOB locus on BMI.

Forty two SNPs spanning the APOB genomic locus with their corresponding meta-analysis (z-based) p-values for the maternally-derived associations (as -log10 values) are plotted as a function of chromosomal position. Estimated recombination rates are plotted to reflect the local LD structure around the associated SNP (blue) and its correlated proxies (red:R2≥0.8; orange:0.5≥R2>0.8; yellow:0.2≥R2>0.5; white:R2<0.2). Combined (Z-based) p-value for APOB SNP rs1367117 excluding JPS is 7.4x10-5 (presented in figure). Corresponding p-value including JPS is 7.8x10-6 (presented in Table 1). *Results used to generate the plot are based on genome-wide data available in FHS, FamHS and ERF (and not including JPS where data are not available). Bioinformatics

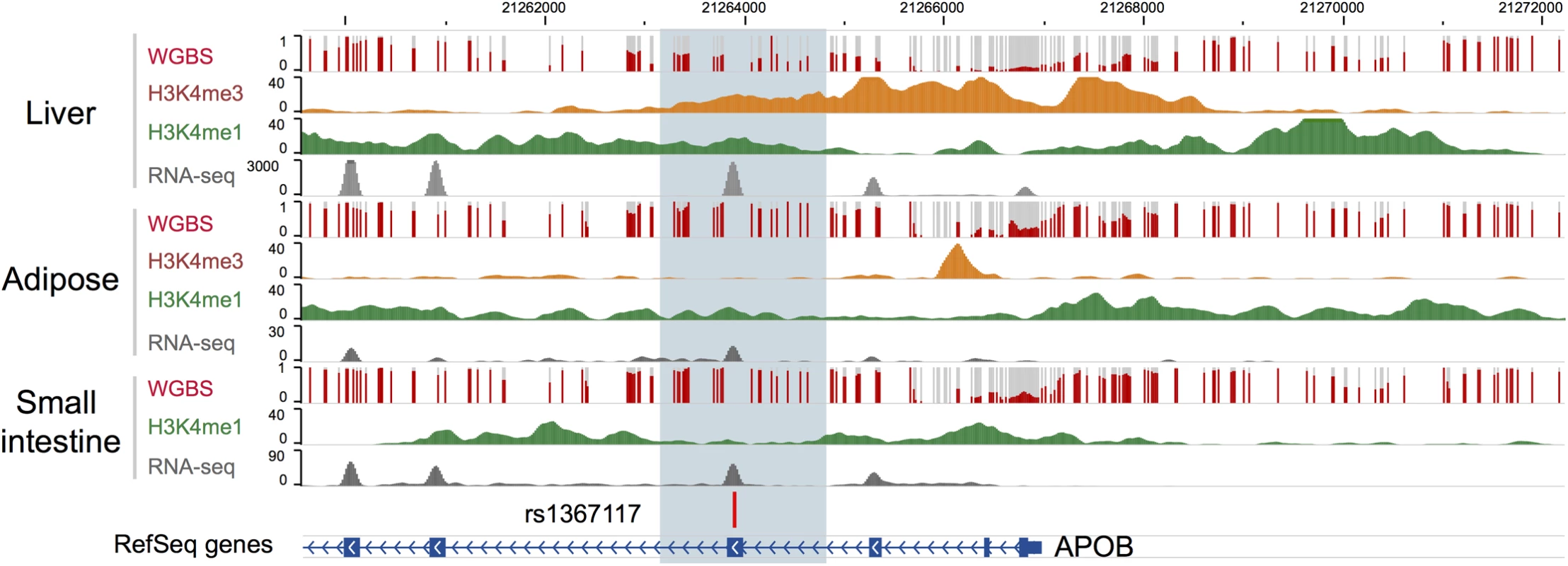

Bioinformatic annotation was undertaken for rs1367117, located within the 4th exon of apoB, using the Epigenome Browser (http://epigenomegateway.wustl.edu/; [28, 29]). The region is depicted in Fig 3. The gene is expressed most abundantly in liver, and far less in small intestine and least in adipose. In liver, there is a broad region with regulatory activity beginning upstream of the promoter and extending past the 4th exon with enhancer activity around exon 4 in both liver and adipose. Therefore, this region displays a variety of regulatory functions. Notably, the DNA methylation in this region spanning exon 4 shows a 50% methylation pattern in liver, consistent with a parent-of-origin effect or allelic-specific methylation; however, the same is not true in adipose and small intestine which show nearly 100% methylation, which might indicate tissue-specific imprinting [30].

Fig. 3. Bioinformatic annotation for the APOB locus.

Bioinformatic annotation was undertaken for rs1367117, located within the 4th exon of the APOB gene, using the Epigenome Browser (http://epigenomegateway.wustl.edu/). APOB gene is shown in the blue track and the focal SNP with a vertical bar. Level of DNA methylation (whole genome bisulfite sequencing, or WGBS), histone marks indicative of promoters (H3K4me3) and enhancers (H3K4me1), and expression levels (RNA-seq) were plotted in three relevant tissues: liver, adipose, and small intestine. Discussion

This study tested the hypothesis that including the parental origin of the allele will reveal parent-of-origin genetic effects on adiposity and glycemic traits among young adults. We have shown that a common coding variant in APOB gene has a significant maternally-derived POE on CMR traits, and adiposity in particular. Our findings for APOB gene provide support for the potential importance of POEs on CMR traits.

Several findings from linkage studies provide evidence for loci demonstrating POEs on CMR traits and phenotypes [13–17]. Yet despite this evidence, few genetic association studies to date have examined POEs on CMR outcomes. In a study conducted in Iceland, GWAS data were used together with genealogy and long-range phasing to examine POEs on incident Type 2 Diabetes (T2D) [18]. Importantly, the Icelandic study demonstrated that the inclusion of the parental source of offspring alleles strengthened the evidence for previously reported associations of T2D with SNPs within imprinted intervals and genes, such as KCNQ1, and revealed novel associations with T2D. Subsequently, POEs were also detected in this population of Icelanders on age at menarche and thyroid-stimulating hormone levels [19, 20], which are related to CMR traits. Other studies have shown that genetic variations in several known imprinted genes, such as IGF2, INS and GNAS, have been associated with CMR traits, including adult obesity (BMI) and T2D [31–36]. GWAS also have identified POEs on body composition in animal models [37, 38] and on high blood pressure [39] in humans. A novel approach for detecting POEs using genome-wide genotype data of unrelated individuals was recently introduced [40]. Using this method 6 SNPs were identified as having POE on BMI, 2 of which, near genes SLC2A10 and KCNK9, were replicated in five family studies. POE was not identified for APOB by that study and we were not able to examine SLC2A10 and KCNK9 in our study as genetic data for these genes were not available in JPS.

Multiple candidate gene studies (e.g. reviewed in [41–45]) and more recently GWAS [8, 27, 46–59] identified genetic variants in APOB gene related to lipid and lipoprotein levels, and to coronary artery disease and myocardial infarction. Specifically, APOB rs1367117, identified here, was shown to be associated with levels of LDL-C, TC, APOB and non-HDL in GWAS [52, 54] and candidate gene studies [60–62] and recently, an epistatic interaction on BP levels was observed between APOB rs1367117 and VCAM1 rs1041163 [63].

SNP rs1367117 is a nonsynonymous missense variant, located in exon 4 of APOB gene, causing a Thr→Ile amino acid change. A study using samples from both Finnish and Mexican subjects has shown that rs1367117 is associated with serum apoB levels, and that another variant identified in GWAS (rs7575840), which is in high LD with rs1367117 (r2 = 0.93 in CEU HapMap sample), is associated with expression levels of APOB gene in adipose tissue [61]. Obesity is strongly associated with dyslipidemia, which may account for the associated increased risk of atherosclerosis and coronary disease. Although the precise mechanism whereby obesity results in dyslipidemia has not been established, there is some evidence to support that visceral obesity is related to dysregulation of both apoB isoforms [64, 65].

Only several studies have shown that genetic variants in APOB gene are associated with body size and obesity in children [66] and adults [67–70] and with body growth and obesity in chicken [71]. Our results showing a highly significant additive genetic effect of APOB rs1367117 on lipid traits and a highly significant maternal-specific effect on adiposity traits, in fact demonstrate why genetic associations studies overlooking POE conducted to date have typically identified associations of APOB gene variants with lipid traits but not with adiposity.

To our knowledge, APOB gene has not been previously reported as demonstrating POEs on CMR or on other traits nor has it been identified as imprinted (and neither has its neighboring genes located within 500kb upstream and downstream of APOB, e.g. C2orf43, GDF7, HS1BP3, HS1BP3-IT1, RHOB, LOC645949). Several explanations may account for the lack of previous support for POEs related to APOB. First, both imprinting and maternal genotype effects on the intrauterine environment are recognized as parent-of-origin mechanisms [10, 72], thus further work is needed to determine which of the mechanisms may explain the parent-of-origin associations identified in this work. Specifically, human placenta produces and secretes apoB-containing lipoproteins, and placental lipoprotein formation constitutes a pathway of lipid transfer from the mother to the developing fetus [73]. Whether this pathway may affect adiposity and cardio-metabolic health of adult offspring remains to be explored. Second, it is assumed that not all human imprinted genes have been identified [74–76] and gradually more genes are recognized as being imprinted [77]. Lastly, and perhaps more likely, parent-of-origin associations may be apparent in specific tissues, specific stages of development or in specific genes which are not themselves imprinted but rather regulated by imprinted genes. A recent work by Mott et al. supports the latter by showing that non-imprinted genes can generate parent-of-origin effects by interaction with imprinted loci and that the importance of the number of imprinted genes is likely secondary to their interactions [78]. It has also been suggested that imprinted genetic effects on complex traits are context dependent, and that imprinting patterns may not be consistent among traits and environments or between sexes [79]. For example, a highly significant QTL on chromosome 1, DMetS1b, was shown to be associated with variation in both serum lipid levels and obesity in mice. Interestingly, for cholesterol there was an additive effect in the full population, whereas for free-fatty acid levels high-fat fed females showed maternal expression imprinting and low-fat fed females showed paternal expression imprinting [80]. Of note, tissue and gender specificity of imprinting has been demonstrated very recently in a study in humans using allele-specific expression data [77]. Similarly, our findings in humans have demonstrated that the same APOB variant has an additive genotype effect on lipids, and yet a maternal POE on adiposity. In addition, context-specificity may underlie the lack of POEs of APOB in the ERF study, possibly due to a specific environmental factor in the Dutch population that could not be accounted for in the models. These hypotheses need to be further explored.

The major strengths of this study are the use of common genetic variation in mother-offspring pairs from a population-based cohort with quantitative CMR traits measured at age 32 and the opportunity to replicate our findings in extended pedigrees from three large family studies. Notably, the family design also minimizes confounding due to population stratification [81, 82]. Additionally, the use of candidate genes identified in GWAS takes advantage of available scientific knowledge as well as reduces the problem of multiple comparisons.

There are also several limitations to our study. First, genetic data on fathers were unavailable in JPS resulting in the use of probability-based imputation of the parental source of minor alleles in heterozygous mother-offspring pairs. However, as we have shown in sensitivity analyses, this approach is likely conservative and therefore preferable compared to excluding heterozygous mother-offspring pairs. Furthermore, replication in other studies where genetic data in extended families were used minimizes this source of bias. Second, the APOB variant indentified here has not been previously reported in large GWAS consortia as related with adiposity. Although this is likely the result of GWAS typically ignoring the parental source of alleles due to lack of family data, there is a possibility that our POE results reflect false-positive findings. To address this, we have conducted simulations applying two different approaches, one for a mother-offspring design (using JPS) and the other for an extended pedigrees design (using FHS). Based on these simulations, maternal permutation p-values were similar to our observed p-values providing further support for the significance of the reported maternal APOB effect. Lastly, environmental exposures around the time of birth may contribute to the context-specificity of POEs. These data were unavailable for most of the participating studies and therefore their effects could not be assessed in this work.

In summary, we have demonstrated that taking into account the parental origin of offspring alleles compared to examining the offspring genotype as a whole may enhance our understanding of genetic associations with CMR traits. Our results highlight the potential contribution of POEs to uncovering complex relations between genetic variants and common traits, and motivate further research in this area, including assessment of the impact of POEs on common traits and investigation of the mechanisms underlying these associations.

Methods

The Jerusalem Perinatal Study (JPS) population-based cohort includes a sub-cohort of all 17,003 births to residents of Jerusalem, between years 1974 and 1976 [83–85]. Data consist of demographic and socioeconomic information, medical conditions of the mother during current and previous pregnancies, and offspring birth weight, abstracted either from birth certificates or maternity ward logbooks. Additional information on lifestyle and maternal medical conditions, including gestational age, mother's smoking status, height and pre-pregnancy weight, end of pregnancy weight and gynecological history, was collected by interviews of mothers on the first or second day postpartum. Data collection methods have been described in detail previously [83–85].

The Jerusalem Perinatal Family Follow-Up Study includes a sample of 1,250 mother-offspring pairs (average offspring age 32, range: 30–35) from the original 1974–1976 birth cohort, who were interviewed and examined between 2007 and 2009. Information on sampling and data collection in the JPS Family Follow-Up study was previously described [86]. Briefly, the sampling frame included singleton term births without congenital malformations, and a stratified sample defined by maternal pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI) and birth weight was obtained, where both low and high birth weight as well as over-weight and obese mothers were over-sampled. Standard procedures and training protocols were used to measure standing height, body weight, waist circumference and blood pressure. Blood specimens collected after fasting for at least 8 hours were taken using standard procedures, and biochemical measurements of insulin, glucose, cholesterol, HDL-C and triglycerides were assayed in plasma. Inter assay coefficients of variation (CV%) were less than 2% for glucose and less than 2.5% for cholesterol, HDL-C and triglycerides.

Individuals who reported taking medication to treat diabetes (n = 13), lipid-lowering medication (n = 13) or BP-lowering medication (n = 11), were excluded from the corresponding analyses.

DNA extraction and genotyping

Blood was collected in tubes containing EDTA. DNA was extracted from white blood cells using standard salting-out extraction procedures. Common tag SNPs from candidate genes in molecular pathways potentially related to both birth weight and CMR phenotypes were previously genotyped in mother-offspring pairs using Illumina 1536 SNPs panel (BeadArray technology with a GoldenGate custom panel, Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA [87, 88]). Of the 1536 SNPs genotyped, 1384 (90.1%) provided genotype clusters with call rates>95%. Additional quality control measures for genotypic data included: 1) testing Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium; SNPs with chi-square p-value < 0.05/1384 were excluded; and 2) observing Mendelian inheritance inconsistency between mother’s and offspring genotypes; SNPs with more than 0.5% inconsistency were excluded. As a result, an additional 10 SNPs were removed and a total of 1374 SNPs, representing 180 genes, were available.

SNP selection

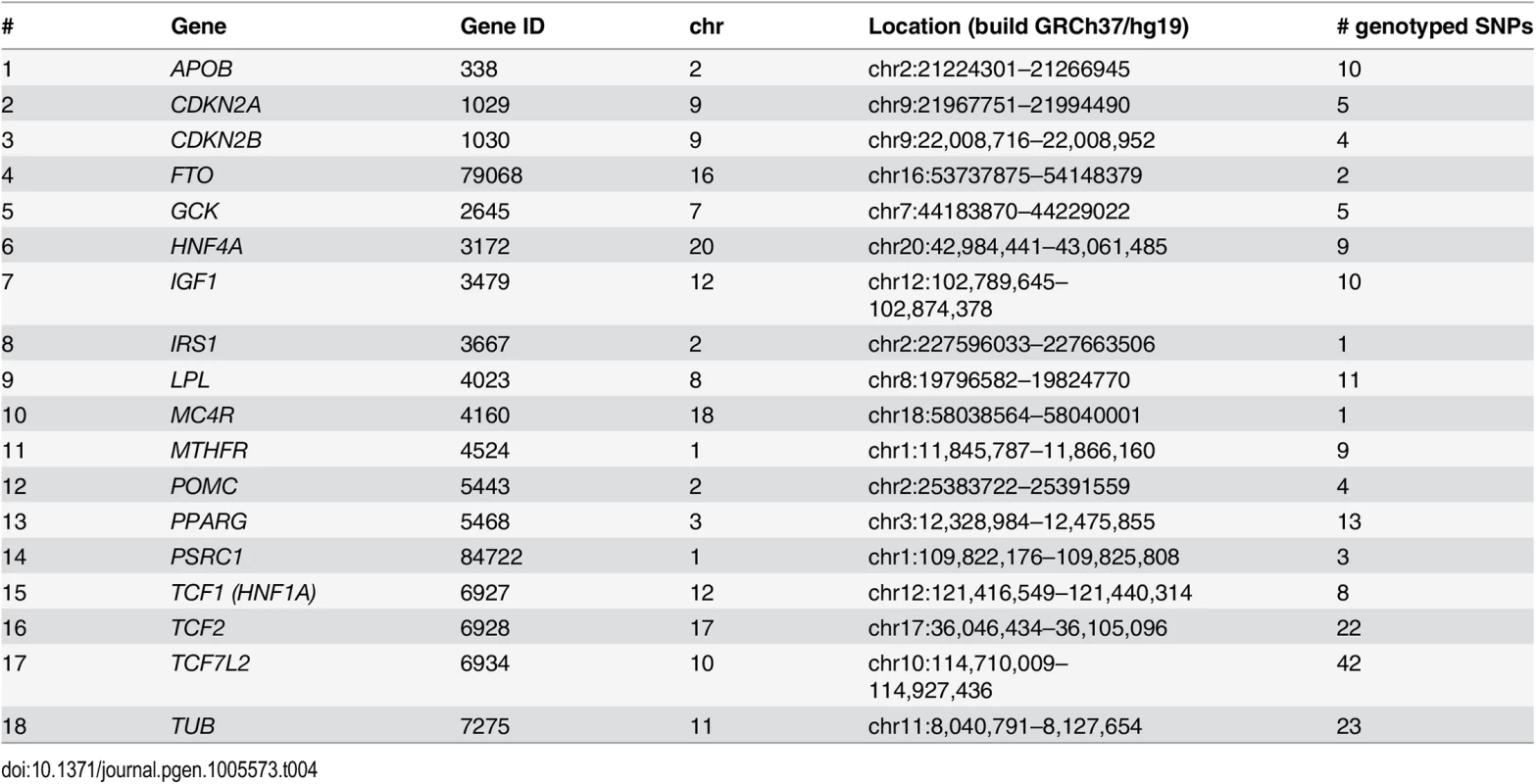

To identify POEs on adiposity and glycemic traits we selected SNPs within genes where previous GWAS in Caucasian populations had revealed variants associated with BMI, glucose and insulin levels, lipids and lipoproteins levels, obesity and type 2 diabetes. This is similar to the approach applied in the Icelandic study in the sense that published GWAS findings were used for targeting variants of interest for POE analysis [18]. Specifically, using the US National Institutes of Health Office of Population Studies catalogue of published genome-wide association studies (www.genome.gov/gwastudies—accessed July 1, 2012) [89], out of the 180 genes genotyped previously using the Illumina custom panel in JPS mother-offspring pairs, we identified 18 genes for which significant associations (p-value<5X10-8) with CMR traits were reported in GWAS (Table 4 and S1 and S2 Tables). In these 18 genes 182 tag SNPs were available in JPS (Table 4 and S3 Table).

Tab. 4. Genes selected for examination of parent-of-origin effects in JPS.

Cardio-metabolic outcomes

The following adiposity and glycemic traits were measured in offspring at age 32: body mass index (BMI, calculated by dividing weight (kg) by squared height (m2)); waist circumference (WC, mean of two consecutive measurements at the midpoint between the lower ribs and iliac crest in the midaxillary line (cm)); fasting glucose (mg/dL) and fasting insulin (mean of two repeated measures (mU/mL), natural log-transformed).

In a follow-up analysis limited to replicated findings, we additionally examined lipid and blood pressure traits: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C (mmol/L)); high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C (mmol/L)), triglycerides (TG (mmol/L), natural log-transformed), systolic and diastolic blood pressure (SBP and DBP, mean of three consecutive measures (mmHg)).

All cardio-metabolic outcomes were treated as continuous variables (distributions presented in S4 Table).

Statistical analyses

Analyses of JPS data were carried out using Stata 12.0 (StataCorp, College Station TX).

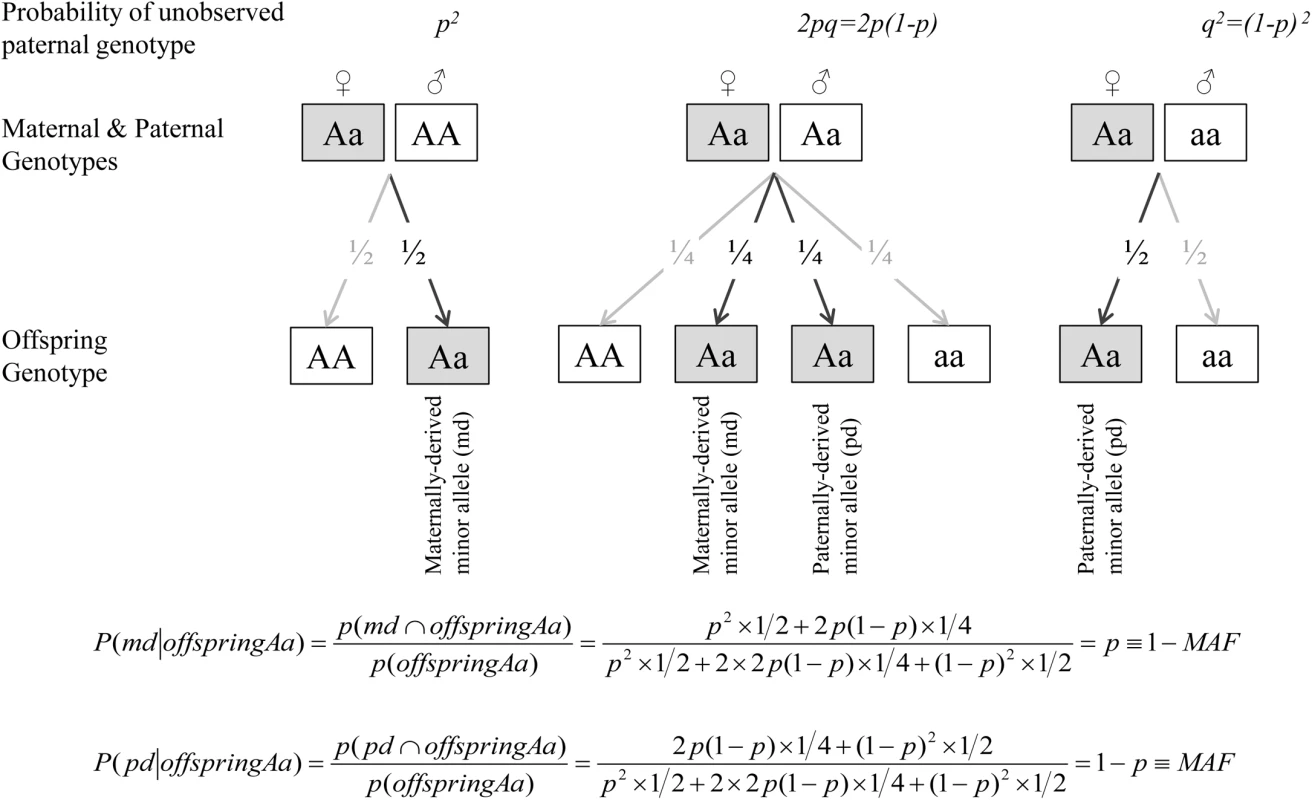

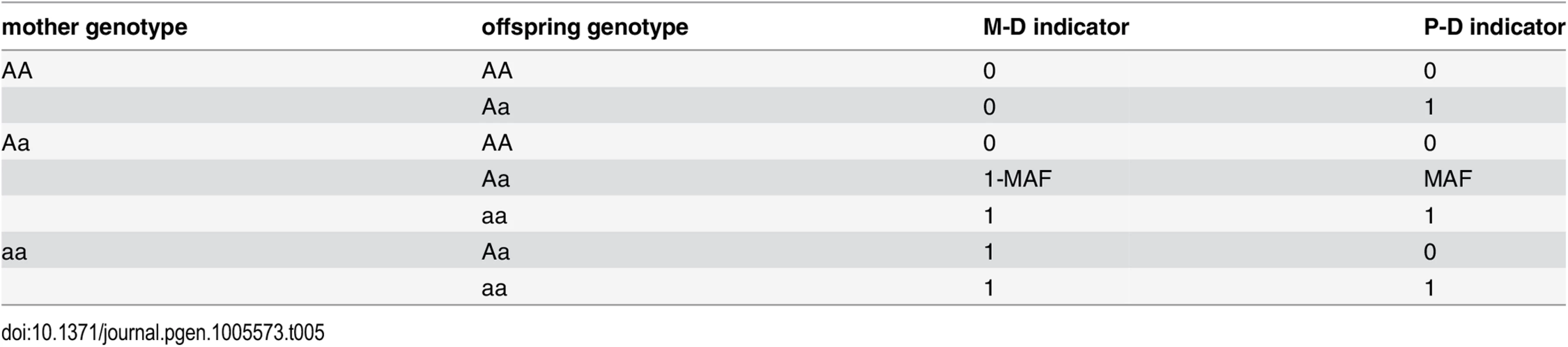

To assess the separate contribution of the maternally - and paternally-inherited variants to offspring CMR phenotypes, we first determined the parental origin of minor alleles, based on mother-offspring pairs, since genetic data on fathers were not available in JPS. For every given SNP we constructed two variables; maternally-derived minor allele (M-D) and paternally-derived minor allele (P-D) indicators. These indicators count the number of minor alleles inherited from mother and/or father; each count is a zero or one (Table 4). When offspring and mother were both heterozygous at a given SNP, the source of the minor allele was ambiguous. But under random mating and transmission equilibrium, the probability that the minor allele was derived from the mother is 1-MAF and from the father is MAF, where MAF = minor allele frequency. Therefore, similarly to use of estimated dosage for uncertain genotypes, for heterozygous mothers-offspring pairs, we used the estimated dosage of M-D and P-D indicators, i.e. 1-MAF and MAF, respectively (Table 5 and Fig 4). The percentage of heterozygous mother-offspring for each of the 182 selected SNPs ranged between 5% and 27% (S3 Table).

Fig. 4. Estimated dosage of maternally- and paternally-derived minor allele indicators for heterozygous (Aa) mothers-offspring pairs.

Tab. 5. Indicators of parental origin of the minor allele in JPS.

When offspring and mother are both heterozygous at a given SNP, the source of the minor allele is ambiguous. For any given SNP with allele frequencies of p and q for the common (A) and minor (a) alleles respectively, the expected paternal genotype frequencies assuming Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium are f(AA) = p2, f(Aa) = 2pq and f(aa) = q2. Under random mating and transmission equilibrium, the probability that the minor allele was derived from the mother is 1-MAF and from the father is MAF, where MAF = minor allele frequency. Therefore, for heterozygous mothers-offspring pairs, we used the estimated dosage of M-D and P-D indicators, i.e. 1-MAF and MAF.

We used linear regression to examine each SNP-trait association. We first assessed the associations of offspring genotype with trait, using an additive genetic model. Then the association of the parental origin of the minor allele on the trait was assessed by including the M-D and P-D indicators together in a single model.

The following mean models were used:

Where Y denotes trait, GO = offspring genotype, GMD = indicator of maternally-derived minor allele, GPD = indicator of paternally-derived allele, and Z = other covariates.

Existence of POE in model 2 was assessed via a test of the following null hypotheses:

(1) βMD = 0; (2) βPD = 0; (3) βMD = βPD. The significance threshold for rejection of the null hypotheses was set at a within-gene corrected Bonferroni p-value<0.05 for the separate effects of the maternally - or paternally derived indicators (i.e. hypotheses 1 or 2) and nominal p-values (i.e. p-values<0.05) for the F-test examining the differences between these effects (i.e. hypothesis 3). Findings that met these criteria for any one of the examined outcomes were moved forward for replication and meta-analysis.

All models were adjusted for offspring sex and ethnicity. Following an approach suggested by Thomas and Witte to correct for population stratification in mixed-ethnicity families [90], ethnicity of offspring was classified based on country of origin of all four grandparents, using nine major ethnicity strata (Israel, Morocco, Other North Africa, Iran, Iraq, Kurdistan, Yemen, Other Asia and the Balkans and Ashkenazi). Rather than allocating offspring to a single ethnicity, we constructed a covariate for each stratum giving the proportion of grandparents derived from each of the nine ethnic groups (ranging from 0 to 1, reflecting none or all four grandparents originating from the specific ethnic group, respectively) and then included these covariates as adjustment variables in a multiple regression, excluding one stratum (Ashkenazi) to eliminate complete multicollinearity.

To account for the stratified sampling, we used Stata’s ‘pweight’ option to weight estimates by individuals’ inverse probability of being sampled [91].

Replication and meta-analysis

Findings exceeding the aforementioned threshold of significance in JPS were followed up in three additional family studies with extended pedigrees: 1) Framingham Heart Study (FHS) (max N = 2225 probands); 2) Family Heart Study (FamHS) (max N = 773 probands); and 3) Erasmus Rucphen Family (ERF) study (max N = 631 probands). Probands were restricted to individuals of European decent, aged≤50, with available genetic and CMR data and genetic data in at least one parent. Probands on medication to treat diabetes, lipid-lowering medication or BP-lowering medication were excluded from the corresponding analyses. Detailed description of each of the studies, including study sample, genotyping techniques and CMR trait measurements and distributions, is provided in S1 Text and S4 Table. Distributions of CMR traits were comparable between the studies, with the exception of fasting insulin in FHS. Yet substantial differences in fasting insulin distributions across studies are commonly observed [92, 93]. We used the quantitative transmission disequilibrium test (QTDT) software [94] to test for the association of maternally and paternally inherited minor alleles using information from the extended families within each study, adjusting for sex and age, using a model similar to the one used in JPS. Specifically, qtdt -at -ot was used to test for POE (maternal effect = paternal effect), and qtdt -at -om and qtdt -at -op were used to test maternal and paternal effects, respectively (modified to adjust for other parent contribution). QTDT software uses a linear mixed effect model to account for familial correlations. We did not use the QTDT statistic that is robust to population stratification because, based on available genome-wide data, population stratification did not affect the traits evaluated in most studies. In limited instances where there was some suggestive evidence for the presence of population stratification, we corrected for it using principal components analysis within the relevant study [95].

Additionally, z-based meta-analysis combining results from all 4 studies (i.e. JPS, FHS, FamHS and ERF) was conducted, as a joint analysis approach was shown to be more efficient than a two-stage approach for genetic association studies [96]. A Bonferroni correction was applied and SNPs were declared statistically significant if their p-values were below 0.05 divided by the total number of SNPs initially tested (N = 182), i.e. p-value<2.75x10-4. We also applied an inverse variance weighted meta-analysis approach to obtain a pooled estimate of effect sizes (betas) across studies. Since the QTDT approach does not provide estimates of standard errors (SEs), SEs were estimated by converting p-values into a z-statistic and setting: SE = beta/z.

Ethics statement

The JPS study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Hadassah-Hebrew University Medical Center (approval #10–01.04.05) and the University of Washington Human Subject Review Committee (approval #31032). FHS was approved by Boston University Medical Center Institutional Review Board (approvals #H–32132, #H–26671 and #H–28859), FamHS was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis (approval #201403014) and ERF study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Erasmus MC, Rotterdam (approval #MEC 213.575/2002/114). All participants provided written informed consent for genetic studies.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. Willer C.J., et al., Six new loci associated with body mass index highlight a neuronal influence on body weight regulation. Nat Genet, 2009. 41(1): p. 25–34. doi: 10.1038/ng.287 19079261

2. Thorleifsson G., et al., Genome-wide association yields new sequence variants at seven loci that associate with measures of obesity. Nat Genet, 2009. 41(1): p. 18–24. doi: 10.1038/ng.274 19079260

3. Dupuis J., et al., New genetic loci implicated in fasting glucose homeostasis and their impact on type 2 diabetes risk. Nat Genet, 2010. 42(2): p. 105–16. doi: 10.1038/ng.520 20081858

4. Meigs J.B., et al., Genome-wide association with diabetes-related traits in the Framingham Heart Study. BMC Med Genet, 2007. 8 Suppl 1: p. S16. 17903298

5. Goldstein D.B., Common genetic variation and human traits. N Engl J Med, 2009. 360(17): p. 1696–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0806284 19369660

6. Manolio T.A., Cohort studies and the genetics of complex disease. Nat Genet, 2009. 41(1): p. 5–6. doi: 10.1038/ng0109-5 19112455

7. Manolio T.A., et al., Finding the missing heritability of complex diseases. Nature, 2009. 461(7265): p. 747–53. doi: 10.1038/nature08494 19812666

8. Sabatti C., et al., Genome-wide association analysis of metabolic traits in a birth cohort from a founder population. Nat Genet, 2009. 41(1): p. 35–46. doi: 10.1038/ng.271 19060910

9. Eichler E.E., et al., Missing heritability and strategies for finding the underlying causes of complex disease. Nat Rev Genet, 2010. 11(6): p. 446–50. doi: 10.1038/nrg2809 20479774

10. Rampersaud E., et al., Investigating parent of origin effects in studies of type 2 diabetes and obesity. Curr Diabetes Rev, 2008. 4(4): p. 329–39. 18991601

11. Reik W. and Walter J., Genomic imprinting: parental influence on the genome. Nat Rev Genet, 2001. 2(1): p. 21–32. 11253064

12. Koerner M.V. and Barlow D.P., Genomic imprinting-an epigenetic gene-regulatory model. Curr Opin Genet Dev, 2010. 20(2): p. 164–70. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2010.01.009 20153958

13. Dong C., et al., Possible genomic imprinting of three human obesity-related genetic loci. Am J Hum Genet, 2005. 76(3): p. 427–37. 15647995

14. Gorlova O.Y., et al., Genetic linkage and imprinting effects on body mass index in children and young adults. Eur J Hum Genet, 2003. 11(6): p. 425–32. 12774034

15. Guo Y.F., et al., Assessment of genetic linkage and parent-of-origin effects on obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2006. 91(10): p. 4001–5. 16835282

16. Lindsay R.S., et al., Genome-wide linkage analysis assessing parent-of-origin effects in the inheritance of type 2 diabetes and BMI in Pima Indians. Diabetes, 2001. 50(12): p. 2850–7. 11723070

17. Reynisdottir I., et al., Localization of a susceptibility gene for type 2 diabetes to chromosome 5q34-q35.2. Am J Hum Genet, 2003. 73(2): p. 323–35. 12851856

18. Kong A., et al., Parental origin of sequence variants associated with complex diseases. Nature, 2009. 462(7275): p. 868–74. doi: 10.1038/nature08625 20016592

19. Gudbjartsson D.F., et al., Large-scale whole-genome sequencing of the Icelandic population. Nat Genet, 2015. 47(5): p. 435–44. doi: 10.1038/ng.3247 25807286

20. Perry J.R., et al., Parent-of-origin-specific allelic associations among 106 genomic loci for age at menarche. Nature, 2014. 514(7520): p. 92–7. doi: 10.1038/nature13545 25231870

21. Falconer D.S. and MacKay T.F.C., Introduction to Quantitative Genetics. 1996, Harlow, Essex, UK: Longmans Green.

22. Murabito J.M., et al., Heritability of age at natural menopause in the Framingham Heart Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2005. 90(6): p. 3427–30. 15769979

23. Brown M.S. and Goldstein J.L., A receptor-mediated pathway for cholesterol homeostasis. Science, 1986. 232(4746): p. 34–47. 3513311

24. Contois J.H., et al., Apolipoprotein B and cardiovascular disease risk: position statement from the AACC Lipoproteins and Vascular Diseases Division Working Group on Best Practices. Clin Chem, 2009. 55(3): p. 407–19. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.118356 19168552

25. de Bakker P.I., et al., Efficiency and power in genetic association studies. Nat Genet, 2005. 37(11): p. 1217–23. 16244653

26. Johnson A.D., et al., SNAP: a web-based tool for identification and annotation of proxy SNPs using HapMap. Bioinformatics, 2008. 24(24): p. 2938–9. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn564 18974171

27. Saxena R., et al., Genome-wide association analysis identifies loci for type 2 diabetes and triglyceride levels. Science, 2007. 316(5829): p. 1331–6. 17463246

28. Zhou X., et al., Exploring long-range genome interactions using the WashU Epigenome Browser. Nat Methods, 2013. 10(5): p. 375–6. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2440 23629413

29. Zhou X., et al., The Human Epigenome Browser at Washington University. Nat Methods, 2011. 8(12): p. 989–90. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1772 22127213

30. Prickett A.R. and Oakey R.J., A survey of tissue-specific genomic imprinting in mammals. Mol Genet Genomics, 2012. 287(8): p. 621–30. doi: 10.1007/s00438-012-0708-6 22821278

31. Gaunt T.R., et al., Positive associations between single nucleotide polymorphisms in the IGF2 gene region and body mass index in adult males. Hum Mol Genet, 2001. 10(14): p. 1491–501. 11448941

32. Weinstein L.S., et al., The role of GNAS and other imprinted genes in the development of obesity. Int J Obes (Lond), 2010. 34(1): p. 6–17.

33. Roth S.M., et al., IGF2 genotype and obesity in men and women across the adult age span. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord, 2002. 26(4): p. 585–7. 12075589

34. Pembrey M., Imprinting and transgenerational modulation of gene expression; human growth as a model. Acta Genet Med Gemellol (Roma), 1996. 45(1–2): p. 111–25.

35. Huxtable S.J., et al., Analysis of parent-offspring trios provides evidence for linkage and association between the insulin gene and type 2 diabetes mediated exclusively through paternally transmitted class III variable number tandem repeat alleles. Diabetes, 2000. 49(1): p. 126–30. 10615960

36. Meigs J.B., et al., The insulin gene variable number tandem repeat and risk of type 2 diabetes in a population-based sample of families and unrelated men and women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2005. 90(2): p. 1137–43. 15562019

37. de Koning D.J., et al., Genome-wide scan for body composition in pigs reveals important role of imprinting. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2000. 97(14): p. 7947–50. 10859367

38. Mantey C., et al., Mapping and exclusion mapping of genomic imprinting effects in mouse F2 families. J Hered, 2005. 96(4): p. 329–38. 15761081

39. Yang J. and Lin S., Detection of imprinting and heterogeneous maternal effects on high blood pressure using Framingham Heart Study data. BMC Proc, 2009. 3 Suppl 7: p. S125. 20017991

40. Hoggart C.J., et al., Novel approach identifies SNPs in SLC2A10 and KCNK9 with evidence for parent-of-origin effect on body mass index. PLoS Genet, 2014. 10(7): p. e1004508. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004508 25078964

41. Benn M., Apolipoprotein B levels, APOB alleles, and risk of ischemic cardiovascular disease in the general population, a review. Atherosclerosis, 2009. 206(1): p. 17–30. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.01.004 19200547

42. de Almeida E.R., et al., The Roles of Genetic Polymorphisms and Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection in Lipid Metabolism. Biomed Res Int, 2013. 2013: p. 836790. doi: 10.1155/2013/836790 24319689

43. Young S.G., Recent progress in understanding apolipoprotein B. Circulation, 1990. 82(5): p. 1574–94. 1977530

44. Chiodini B.D., et al., APO B gene polymorphisms and coronary artery disease: a meta-analysis. Atherosclerosis, 2003. 167(2): p. 355–66. 12818419

45. Boekholdt S.M., et al., Molecular variation at the apolipoprotein B gene locus in relation to lipids and cardiovascular disease: a systematic meta-analysis. Hum Genet, 2003. 113(5): p. 417–25. 12942366

46. Makela K.M., et al., Genome-wide association study pinpoints a new functional apolipoprotein B variant influencing oxidized low-density lipoprotein levels but not cardiovascular events: AtheroRemo Consortium. Circ Cardiovasc Genet, 2013. 6(1): p. 73–81. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.112.964965 23247145

47. Chu A.Y., et al., Genome-wide association study evaluating lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 mass and activity at baseline and after rosuvastatin therapy. Circ Cardiovasc Genet, 2012. 5(6): p. 676–85. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.112.963314 23118302

48. Inouye M., et al., Novel Loci for metabolic networks and multi-tissue expression studies reveal genes for atherosclerosis. PLoS Genet, 2012. 8(8): p. e1002907. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002907 22916037

49. Kristiansson K., et al., Genome-wide screen for metabolic syndrome susceptibility Loci reveals strong lipid gene contribution but no evidence for common genetic basis for clustering of metabolic syndrome traits. Circ Cardiovasc Genet, 2012. 5(2): p. 242–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.111.961482 22399527

50. Middelberg R.P., et al., Genetic variants in LPL, OASL and TOMM40/APOE-C1-C2-C4 genes are associated with multiple cardiovascular-related traits. BMC Med Genet, 2011. 12: p. 123. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-12-123 21943158

51. Waterworth D.M., et al., Genetic variants influencing circulating lipid levels and risk of coronary artery disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, 2010. 30(11): p. 2264–76. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.201020 20864672

52. Teslovich T.M., et al., Biological, clinical and population relevance of 95 loci for blood lipids. Nature, 2010. 466(7307): p. 707–13. doi: 10.1038/nature09270 20686565

53. Johansen C.T., et al., Excess of rare variants in genes identified by genome-wide association study of hypertriglyceridemia. Nat Genet, 2010. 42(8): p. 684–7. doi: 10.1038/ng.628 20657596

54. Chasman D.I., et al., Forty-three loci associated with plasma lipoprotein size, concentration, and cholesterol content in genome-wide analysis. PLoS Genet, 2009. 5(11): p. e1000730. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000730 19936222

55. Aulchenko Y.S., et al., Loci influencing lipid levels and coronary heart disease risk in 16 European population cohorts. Nat Genet, 2009. 41(1): p. 47–55. doi: 10.1038/ng.269 19060911

56. Kathiresan S., et al., Common variants at 30 loci contribute to polygenic dyslipidemia. Nat Genet, 2009. 41(1): p. 56–65. doi: 10.1038/ng.291 19060906

57. Sandhu M.S., et al., LDL-cholesterol concentrations: a genome-wide association study. Lancet, 2008. 371(9611): p. 483–91. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60208-1 18262040

58. Kathiresan S., et al., Six new loci associated with blood low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol or triglycerides in humans. Nat Genet, 2008. 40(2): p. 189–97. doi: 10.1038/ng.75 18193044

59. Willer C.J., et al., Newly identified loci that influence lipid concentrations and risk of coronary artery disease. Nat Genet, 2008. 40(2): p. 161–9. doi: 10.1038/ng.76 18193043

60. Benn M., et al., Common and rare alleles in apolipoprotein B contribute to plasma levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in the general population. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2008. 93(3): p. 1038–45. 18160469

61. Haas B.E., et al., Evidence of how rs7575840 influences apolipoprotein B-containing lipid particles. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, 2011. 31(5): p. 1201–7. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.224139 21393584

62. Costanza M.C., et al., Consistency between cross-sectional and longitudinal SNP: blood lipid associations. Eur J Epidemiol, 2012. 27(2): p. 131–8. doi: 10.1007/s10654-012-9670-1 22407430

63. Ndiaye N.C., et al., Epistatic study reveals two genetic interactions in blood pressure regulation. BMC Med Genet, 2013. 14: p. 2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-14-2 23298194

64. Wong A.T., et al., Plasma Apolipoprotein B–48 Transport in Obese Men: a New Tracer Kinetic Study in the Postprandial State. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2013.

65. Chan D.C., et al., Apolipoprotein B–100 kinetics in visceral obesity: associations with plasma apolipoprotein C-III concentration. Metabolism, 2002. 51(8): p. 1041–6. 12145779

66. Hu P., et al., Effect of apolipoprotein B polymorphism on body mass index, serum protein and lipid profiles in children of Guangxi, China. Ann Hum Biol, 2009. 36(4): p. 411–20. doi: 10.1080/03014460902882475 19449275

67. Rajput-Williams J., et al., Variation of apolipoprotein-B gene is associated with obesity, high blood cholesterol levels, and increased risk of coronary heart disease. Lancet, 1988. 2(8626–8627): p. 1442–6. 2904569

68. Saha N., et al., DNA polymorphisms of the apolipoprotein B gene are associated with obesity and serum lipids in healthy Indians in Singapore. Clin Genet, 1993. 44(3): p. 113–20. 8275568

69. Pouliot M.C., et al., ApoB–100 gene EcoRI polymorphism. Relations to plasma lipoprotein changes associated with abdominal visceral obesity. Arterioscler Thromb, 1994. 14(4): p. 527–33. 7908536

70. Phillips C.M., et al., Gene-nutrient interactions and gender may modulate the association between ApoA1 and ApoB gene polymorphisms and metabolic syndrome risk. Atherosclerosis, 2011. 214(2): p. 408–14. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.10.029 21122859

71. Zhang S., Li H., and Shi H., Single marker and haplotype analysis of the chicken apolipoprotein B gene T123G and D9500D9 - polymorphism reveals association with body growth and obesity. Poult Sci, 2006. 85(2): p. 178–84. 16523611

72. Buyske S., Maternal genotype effects can alias case genotype effects in case-control studies. Eur J Hum Genet, 2008. 16(7): p. 783–5. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2008.74 18398431

73. Madsen E.M., et al., Human placenta secretes apolipoprotein B-100-containing lipoproteins. J Biol Chem, 2004. 279(53): p. 55271–6. 15504742

74. Schulz R., et al., Chromosome-wide identification of novel imprinted genes using microarrays and uniparental disomies. Nucleic Acids Res, 2006. 34(12): p. e88. 16855283

75. Glaser R.L., Ramsay J.P., and Morison I.M., The imprinted gene and parent-of-origin effect database now includes parental origin of de novo mutations. Nucleic Acids Res, 2006. 34(Database issue): p. D29–31. 16381868

76. Morison I.M., Ramsay J.P., and Spencer H.G., A census of mammalian imprinting. Trends Genet, 2005. 21(8): p. 457–65. 15990197

77. Baran Y., et al., The landscape of genomic imprinting across diverse adult human tissues. Genome Res, 2015. 25(7): p. 927–36. doi: 10.1101/gr.192278.115 25953952

78. Mott R., et al., The architecture of parent-of-origin effects in mice. Cell, 2014. 156(1–2): p. 332–42. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.11.043 24439386

79. Lawson H.A., Cheverud J.M., and Wolf J.B., Genomic imprinting and parent-of-origin effects on complex traits. Nat Rev Genet, 2013. 14(9): p. 609–17. doi: 10.1038/nrg3543 23917626

80. Lawson H.A., et al., Genetic effects at pleiotropic loci are context-dependent with consequences for the maintenance of genetic variation in populations. PLoS Genet, 2011. 7(9): p. e1002256. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002256 21931559

81. Gauderman W.J., Candidate gene association analysis for a quantitative trait, using parent-offspring trios. Genet Epidemiol, 2003. 25(4): p. 327–38. 14639702

82. Wheeler E. and Cordell H.J., Quantitative trait association in parent offspring trios: Extension of case/pseudocontrol method and comparison of prospective and retrospective approaches. Genet Epidemiol, 2007. 31(8): p. 813–33. 17549757

83. Davies A.M., et al., The Jerusalem perinatal study. 1. Design and organization of a continuing, community-based, record-linked survey. Isr J Med Sci, 1969. 5(6): p. 1095–106. 5365594

84. Harlap S., et al., The Jerusalem Perinatal Study cohort, 1964–2005: methods and a review of the main results. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol, 2007. 21(3): p. 256–73. 17439536

85. Harlap S., et al., The Jerusalem perinatal study: the first decade 1964–73. Isr J Med Sci, 1977. 13(11): p. 1073–91. 591301

86. Hochner H., et al., Associations of maternal prepregnancy body mass index and gestational weight gain with adult offspring cardiometabolic risk factors: the Jerusalem Perinatal Family Follow-up Study. Circulation, 2012. 125(11): p. 1381–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.070060 22344037

87. Kote-Jarai Z., et al., Seven prostate cancer susceptibility loci identified by a multi-stage genome-wide association study. Nat Genet, 2011. 43(8): p. 785–91. doi: 10.1038/ng.882 21743467

88. http://www.illumina.com/science/publications/publications-list.html.

89. Hindorff, L.A., et al., A Catalog of Published Genome-Wide Association Studies. p. www.genome.gov/gwastudies.

90. Thomas D.C. and Witte J.S., Point: population stratification: a problem for case-control studies of candidate-gene associations? Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 2002. 11(6): p. 505–12. 12050090

91. Horvitz D.G. and Thompson D.J., A generalization of sampling without replacement from a finite universe. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 1952. 47(260): p. 663–85.

92. Robbins D.C., et al., Report of the American Diabetes Association's Task Force on standardization of the insulin assay. Diabetes, 1996. 45(2): p. 242–56. 8549870

93. Dupuis J., et al., New genetic loci implicated in fasting glucose homeostasis and their impact on type 2 diabetes risk. Nat Genet, 2010. 42(2): p. 105–16. doi: 10.1038/ng.520 20081858

94. Abecasis G.R., Cookson W.O., and Cardon L.R., Pedigree tests of transmission disequilibrium. Eur J Hum Genet, 2000. 8(7): p. 545–51. 10909856

95. Price A.L., et al., Principal components analysis corrects for stratification in genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet, 2006. 38(8): p. 904–9. 16862161

96. Skol A.D., et al., Joint analysis is more efficient than replication-based analysis for two-stage genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet, 2006. 38(2): p. 209–13. 16415888

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukčná medicína

Článek Evidence of Selection against Complex Mitotic-Origin Aneuploidy during Preimplantation DevelopmentČlánek A Novel Route Controlling Begomovirus Resistance by the Messenger RNA Surveillance Factor PelotaČlánek A Follicle Rupture Assay Reveals an Essential Role for Follicular Adrenergic Signaling in OvulationČlánek Canonical Poly(A) Polymerase Activity Promotes the Decay of a Wide Variety of Mammalian Nuclear RNAsČlánek FANCI Regulates Recruitment of the FA Core Complex at Sites of DNA Damage Independently of FANCD2Článek Hsp90-Associated Immunophilin Homolog Cpr7 Is Required for the Mitotic Stability of [URE3] Prion inČlánek The Dedicated Chaperone Acl4 Escorts Ribosomal Protein Rpl4 to Its Nuclear Pre-60S Assembly SiteČlánek Chromatin-Remodelling Complex NURF Is Essential for Differentiation of Adult Melanocyte Stem CellsČlánek A Systems Approach Identifies Essential FOXO3 Functions at Key Steps of Terminal ErythropoiesisČlánek Integration of Posttranscriptional Gene Networks into Metabolic Adaptation and Biofilm Maturation inČlánek Lateral and End-On Kinetochore Attachments Are Coordinated to Achieve Bi-orientation in OocytesČlánek MET18 Connects the Cytosolic Iron-Sulfur Cluster Assembly Pathway to Active DNA Demethylation in

Článok vyšiel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Najčítanejšie tento týždeň

2015 Číslo 10- Gynekologové a odborníci na reprodukční medicínu se sejdou na prvním virtuálním summitu

- Je „freeze-all“ pro všechny? Odborníci na fertilitu diskutovali na virtuálním summitu

-

Všetky články tohto čísla

- Gene-Regulatory Logic to Induce and Maintain a Developmental Compartment

- A Decad(e) of Reasons to Contribute to a PLOS Community-Run Journal

- DNA Methylation Landscapes of Human Fetal Development

- Single Strand Annealing Plays a Major Role in RecA-Independent Recombination between Repeated Sequences in the Radioresistant Bacterium

- Evidence of Selection against Complex Mitotic-Origin Aneuploidy during Preimplantation Development

- Transcriptional Derepression Uncovers Cryptic Higher-Order Genetic Interactions

- Silencing of X-Linked MicroRNAs by Meiotic Sex Chromosome Inactivation

- Virus Satellites Drive Viral Evolution and Ecology

- A Novel Route Controlling Begomovirus Resistance by the Messenger RNA Surveillance Factor Pelota

- Sequence to Medical Phenotypes: A Framework for Interpretation of Human Whole Genome DNA Sequence Data

- Your Data to Explore: An Interview with Anne Wojcicki

- Modulation of Ambient Temperature-Dependent Flowering in by Natural Variation of

- The Ciliopathy Protein CC2D2A Associates with NINL and Functions in RAB8-MICAL3-Regulated Vesicle Trafficking

- PPP2R5C Couples Hepatic Glucose and Lipid Homeostasis

- DCA1 Acts as a Transcriptional Co-activator of DST and Contributes to Drought and Salt Tolerance in Rice

- Intermediate Levels of CodY Activity Are Required for Derepression of the Branched-Chain Amino Acid Permease, BraB

- "Missing" G x E Variation Controls Flowering Time in

- The Rise and Fall of an Evolutionary Innovation: Contrasting Strategies of Venom Evolution in Ancient and Young Animals

- Type IV Collagen Controls the Axogenesis of Cerebellar Granule Cells by Regulating Basement Membrane Integrity in Zebrafish

- Loss of a Conserved tRNA Anticodon Modification Perturbs Plant Immunity

- Genome-Wide Association Analysis of Adaptation Using Environmentally Predicted Traits

- Oriented Cell Division in the . Embryo Is Coordinated by G-Protein Signaling Dependent on the Adhesion GPCR LAT-1

- Disproportionate Contributions of Select Genomic Compartments and Cell Types to Genetic Risk for Coronary Artery Disease

- A Follicle Rupture Assay Reveals an Essential Role for Follicular Adrenergic Signaling in Ovulation

- The RNAPII-CTD Maintains Genome Integrity through Inhibition of Retrotransposon Gene Expression and Transposition

- Canonical Poly(A) Polymerase Activity Promotes the Decay of a Wide Variety of Mammalian Nuclear RNAs

- Allelic Variation of Cytochrome P450s Drives Resistance to Bednet Insecticides in a Major Malaria Vector

- SCARN a Novel Class of SCAR Protein That Is Required for Root-Hair Infection during Legume Nodulation

- IBR5 Modulates Temperature-Dependent, R Protein CHS3-Mediated Defense Responses in

- NINL and DZANK1 Co-function in Vesicle Transport and Are Essential for Photoreceptor Development in Zebrafish

- Decay-Initiating Endoribonucleolytic Cleavage by RNase Y Is Kept under Tight Control via Sequence Preference and Sub-cellular Localisation

- Large-Scale Analysis of Kinase Signaling in Yeast Pseudohyphal Development Identifies Regulation of Ribonucleoprotein Granules

- FANCI Regulates Recruitment of the FA Core Complex at Sites of DNA Damage Independently of FANCD2

- LINE-1 Mediated Insertion into (Protein of Centriole 1 A) Causes Growth Insufficiency and Male Infertility in Mice

- Hsp90-Associated Immunophilin Homolog Cpr7 Is Required for the Mitotic Stability of [URE3] Prion in

- Genome-Scale Mapping of σ Reveals Widespread, Conserved Intragenic Binding

- Uncovering Hidden Layers of Cell Cycle Regulation through Integrative Multi-omic Analysis

- Functional Diversification of Motor Neuron-specific Enhancers during Evolution

- The GTP- and Phospholipid-Binding Protein TTD14 Regulates Trafficking of the TRPL Ion Channel in Photoreceptor Cells

- The Gyc76C Receptor Guanylyl Cyclase and the Foraging cGMP-Dependent Kinase Regulate Extracellular Matrix Organization and BMP Signaling in the Developing Wing of

- The Ty1 Retrotransposon Restriction Factor p22 Targets Gag

- Functional Impact and Evolution of a Novel Human Polymorphic Inversion That Disrupts a Gene and Creates a Fusion Transcript

- The Dedicated Chaperone Acl4 Escorts Ribosomal Protein Rpl4 to Its Nuclear Pre-60S Assembly Site

- The Influence of Age and Sex on Genetic Associations with Adult Body Size and Shape: A Large-Scale Genome-Wide Interaction Study

- Parent-of-Origin Effects of the Gene on Adiposity in Young Adults

- Chromatin-Remodelling Complex NURF Is Essential for Differentiation of Adult Melanocyte Stem Cells

- Retinoic Acid Receptors Control Spermatogonia Cell-Fate and Induce Expression of the SALL4A Transcription Factor

- A Systems Approach Identifies Essential FOXO3 Functions at Key Steps of Terminal Erythropoiesis

- Protein O-Glucosyltransferase 1 (POGLUT1) Promotes Mouse Gastrulation through Modification of the Apical Polarity Protein CRUMBS2

- KIF7 Controls the Proliferation of Cells of the Respiratory Airway through Distinct Microtubule Dependent Mechanisms

- Integration of Posttranscriptional Gene Networks into Metabolic Adaptation and Biofilm Maturation in

- Lateral and End-On Kinetochore Attachments Are Coordinated to Achieve Bi-orientation in Oocytes

- Protein Homeostasis Imposes a Barrier on Functional Integration of Horizontally Transferred Genes in Bacteria

- A New Method for Detecting Associations with Rare Copy-Number Variants

- Histone H2AFX Links Meiotic Chromosome Asynapsis to Prophase I Oocyte Loss in Mammals

- The Genomic Aftermath of Hybridization in the Opportunistic Pathogen

- A Role for the Chaperone Complex BAG3-HSPB8 in Actin Dynamics, Spindle Orientation and Proper Chromosome Segregation during Mitosis

- Establishment of a Developmental Compartment Requires Interactions between Three Synergistic -regulatory Modules

- Regulation of Spore Formation by the SpoIIQ and SpoIIIA Proteins

- Association of the Long Non-coding RNA Steroid Receptor RNA Activator (SRA) with TrxG and PRC2 Complexes

- Alkaline Ceramidase 3 Deficiency Results in Purkinje Cell Degeneration and Cerebellar Ataxia Due to Dyshomeostasis of Sphingolipids in the Brain

- ACLY and ACC1 Regulate Hypoxia-Induced Apoptosis by Modulating ETV4 via α-ketoglutarate

- Quantitative Differences in Nuclear β-catenin and TCF Pattern Embryonic Cells in .

- HENMT1 and piRNA Stability Are Required for Adult Male Germ Cell Transposon Repression and to Define the Spermatogenic Program in the Mouse

- Axon Regeneration Is Regulated by Ets–C/EBP Transcription Complexes Generated by Activation of the cAMP/Ca Signaling Pathways

- A Phenomic Scan of the Norfolk Island Genetic Isolate Identifies a Major Pleiotropic Effect Locus Associated with Metabolic and Renal Disorder Markers

- The Roles of CDF2 in Transcriptional and Posttranscriptional Regulation of Primary MicroRNAs

- A Genetic Cascade of Modulates Nucleolar Size and rRNA Pool in

- Inter-population Differences in Retrogene Loss and Expression in Humans

- Cationic Peptides Facilitate Iron-induced Mutagenesis in Bacteria

- EP4 Receptor–Associated Protein in Macrophages Ameliorates Colitis and Colitis-Associated Tumorigenesis

- Fungal Infection Induces Sex-Specific Transcriptional Changes and Alters Sexual Dimorphism in the Dioecious Plant

- FLCN and AMPK Confer Resistance to Hyperosmotic Stress via Remodeling of Glycogen Stores

- MET18 Connects the Cytosolic Iron-Sulfur Cluster Assembly Pathway to Active DNA Demethylation in

- Sex Bias and Maternal Contribution to Gene Expression Divergence in Blastoderm Embryos

- Transcriptional and Linkage Analyses Identify Loci that Mediate the Differential Macrophage Response to Inflammatory Stimuli and Infection

- Mre11 and Blm-Dependent Formation of ALT-Like Telomeres in Ku-Deficient

- Genome Wide Identification of SARS-CoV Susceptibility Loci Using the Collaborative Cross

- Identification of a Single Strand Origin of Replication in the Integrative and Conjugative Element ICE of

- The Type VI Secretion TssEFGK-VgrG Phage-Like Baseplate Is Recruited to the TssJLM Membrane Complex via Multiple Contacts and Serves As Assembly Platform for Tail Tube/Sheath Polymerization

- The Dynamic Genome and Transcriptome of the Human Fungal Pathogen and Close Relative

- Secondary Structure across the Bacterial Transcriptome Reveals Versatile Roles in mRNA Regulation and Function

- ROS-Induced JNK and p38 Signaling Is Required for Unpaired Cytokine Activation during Regeneration

- Pelle Modulates dFoxO-Mediated Cell Death in

- PLOS Genetics

- Archív čísel

- Aktuálne číslo

- Informácie o časopise

Najčítanejšie v tomto čísle- Single Strand Annealing Plays a Major Role in RecA-Independent Recombination between Repeated Sequences in the Radioresistant Bacterium

- The Rise and Fall of an Evolutionary Innovation: Contrasting Strategies of Venom Evolution in Ancient and Young Animals

- Genome Wide Identification of SARS-CoV Susceptibility Loci Using the Collaborative Cross

- DCA1 Acts as a Transcriptional Co-activator of DST and Contributes to Drought and Salt Tolerance in Rice

Prihlásenie#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zabudnuté hesloZadajte e-mailovú adresu, s ktorou ste vytvárali účet. Budú Vám na ňu zasielané informácie k nastaveniu nového hesla.

- Časopisy