-

Články

- Časopisy

- Kurzy

- Témy

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

A Effector with Enhanced Inhibitory

Activity on the NF-κB Pathway Activates the NLRP3/ASC/Caspase-1 Inflammasome

in Macrophages

A type III secretion system (T3SS) in pathogenic Yersinia

species functions to translocate Yop effectors, which modulate cytokine

production and regulate cell death in macrophages. Distinct pathways of

T3SS-dependent cell death and caspase-1 activation occur in

Yersinia-infected macrophages. One pathway of cell death

and caspase-1 activation in macrophages requires the effector YopJ. YopJ is an

acetyltransferase that inactivates MAPK kinases and IKKβ to cause

TLR4-dependent apoptosis in naïve macrophages. A YopJ isoform in Y.

pestis KIM (YopJKIM) has two amino acid substitutions,

F177L and K206E, not present in YopJ proteins of Y.

pseudotuberculosis and Y. pestis CO92. As compared

to other YopJ isoforms, YopJKIM causes increased apoptosis, caspase-1

activation, and secretion of IL-1β in Yersinia-infected

macrophages. The molecular basis for increased apoptosis and activation of

caspase-1 by YopJKIM in Yersinia-infected

macrophages was studied. Site directed mutagenesis showed that the F177L and

K206E substitutions in YopJKIM were important for enhanced apoptosis,

caspase-1 activation, and IL-1β secretion. As compared to

YopJCO92, YopJKIM displayed an enhanced capacity to

inhibit phosphorylation of IκB-α in macrophages and to bind IKKβ in

vitro. YopJKIM also showed a moderately increased ability to inhibit

phosphorylation of MAPKs. Increased caspase-1 cleavage and IL-1β secretion

occurred in IKKβ-deficient macrophages infected with Y.

pestis expressing YopJCO92, confirming that the

NF-κB pathway can negatively regulate inflammasome activation.

K+ efflux, NLRP3 and ASC were important for secretion of

IL-1β in response to Y. pestis KIM infection as shown using

macrophages lacking inflammasome components or by the addition of exogenous KCl.

These data show that caspase-1 is activated in naïve macrophages in

response to infection with a pathogen that inhibits IKKβ and MAPK kinases

and induces TLR4-dependent apoptosis. This pro-inflammatory form of apoptosis

may represent an early innate immune response to highly virulent pathogens such

as Y. pestis KIM that have evolved an enhanced ability to

inhibit host signaling pathways.

Published in the journal: A Effector with Enhanced Inhibitory Activity on the NF-κB Pathway Activates the NLRP3/ASC/Caspase-1 Inflammasome in Macrophages. PLoS Pathog 7(4): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1002026

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1002026Summary

A type III secretion system (T3SS) in pathogenic Yersinia

species functions to translocate Yop effectors, which modulate cytokine

production and regulate cell death in macrophages. Distinct pathways of

T3SS-dependent cell death and caspase-1 activation occur in

Yersinia-infected macrophages. One pathway of cell death

and caspase-1 activation in macrophages requires the effector YopJ. YopJ is an

acetyltransferase that inactivates MAPK kinases and IKKβ to cause

TLR4-dependent apoptosis in naïve macrophages. A YopJ isoform in Y.

pestis KIM (YopJKIM) has two amino acid substitutions,

F177L and K206E, not present in YopJ proteins of Y.

pseudotuberculosis and Y. pestis CO92. As compared

to other YopJ isoforms, YopJKIM causes increased apoptosis, caspase-1

activation, and secretion of IL-1β in Yersinia-infected

macrophages. The molecular basis for increased apoptosis and activation of

caspase-1 by YopJKIM in Yersinia-infected

macrophages was studied. Site directed mutagenesis showed that the F177L and

K206E substitutions in YopJKIM were important for enhanced apoptosis,

caspase-1 activation, and IL-1β secretion. As compared to

YopJCO92, YopJKIM displayed an enhanced capacity to

inhibit phosphorylation of IκB-α in macrophages and to bind IKKβ in

vitro. YopJKIM also showed a moderately increased ability to inhibit

phosphorylation of MAPKs. Increased caspase-1 cleavage and IL-1β secretion

occurred in IKKβ-deficient macrophages infected with Y.

pestis expressing YopJCO92, confirming that the

NF-κB pathway can negatively regulate inflammasome activation.

K+ efflux, NLRP3 and ASC were important for secretion of

IL-1β in response to Y. pestis KIM infection as shown using

macrophages lacking inflammasome components or by the addition of exogenous KCl.

These data show that caspase-1 is activated in naïve macrophages in

response to infection with a pathogen that inhibits IKKβ and MAPK kinases

and induces TLR4-dependent apoptosis. This pro-inflammatory form of apoptosis

may represent an early innate immune response to highly virulent pathogens such

as Y. pestis KIM that have evolved an enhanced ability to

inhibit host signaling pathways.Introduction

Microbial pathogens encode numerous types of virulence factors that are used to circumvent or usurp immune responses within cells of their hosts. A protein export pathway known as the type III secretion system (T3SS) allows Gram-negative bacterial pathogens to deliver effector proteins into or across the plasma membrane of host cells, with the goal of co-opting or disrupting eukaryotic signaling pathways [1], [2]. Infection of macrophages with T3SS-expressing bacterial pathogens commonly causes cytotoxicity in the host cell, but the mechanisms of cellular demise and the morphological and immunological characteristics of cell death can be unique for each microbe [3]. Two types of macrophage death that can be induced by T3SS-expressing pathogens and distinguished morphologically and immunologically are apoptosis and pyroptosis [4]. Apoptosis is traditionally associated with a lack of inflammation while pyroptosis is considered pro-inflammatory [4], [5]. Apoptosis and pyroptosis can also be distinguished mechanistically by the fact that only the latter mechanism of cell death is dependent upon the activity of caspase-1, a pro-inflammatory caspase [4], [5]. Recently, however it has been determined that caspase-1 can be activated in macrophages dying of apoptosis [6], [7], [8], indicating that pathogen-inflicted apoptosis may not be immunologically silent.

Caspase-1 is synthesized as a 45 kDa inactive zymogen that is cleaved to generate the active heterotetramer composed of two p10 and two p20 subunits [9]. Activation of caspase-1 occurs through its recruitment to an inflammasome complex [10], [11], [12]. Activated caspase-1 cleaves pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18, and promotes secretion of the mature forms of these cytokines by a non-conventional pathway. Macrophages dying of pyroptosis therefore release active forms of IL-1β, and IL-18, which are important cytokines for protective host responses against several pathogens [5]. In addition, pyroptosis can release intracellular bacteria from macrophages, allowing for clearance of the pathogens by neutrophils [13].

Inflammasome complexes assemble on a scaffold of NOD-like receptors (NLRs) [11], [12], [14]. NLRs comprise a family of pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) that detect cytosolic pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) or infection-associated processes [10], [11], [12]. Well-studied NLR family members include NLRP3 (formerly NALP3 or Cryopyrin), NLRC4 (formerly IPAF) and NAIP5. NLRP3 in complex with the adaptor protein ASC induces the activation of caspase-1 in response to a variety of microbial products as well as endogenous danger signals such as potassium (K+) efflux or extracellular ATP [10], [11], [12]. NLRC4 recognizes bacterial flagellin from S. enterica serovar Typhimurium, which is delivered into macrophages via a T3SS in this pathogen [10], [13], [15], [16], [17]. Another family of PRRs, the toll-like receptors (TLRs) often function in concert with NLRs to positively regulate inflammasome activation and function [18]. For example, production of pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18 is upregulated by TLR signaling. In addition, production of NLRP3 is positively regulated by TLR signaling through the NF-κB pathway [19].

In pathogenic Yersinia species, a plasmid-encoded T3SS delivers Yop effectors into host cells [2], allowing the bacteria to modulate innate immune responses [20]. The T3SS is an essential virulence determinant in these pathogens, which cause diseases ranging from plague (Y. pestis) to enterocolitis (Y. enterocolitica) and mesenteric lymphadenitis (Y. pseudotuberculosis). Naïve Yersinia-infected macrophages undergo apoptosis via a cell death program that requires TLR4-dependent activation of initiator and executioner caspases and T3SS-mediated delivery of YopJ, which inhibits expression of anti-apoptotic factors under regulatory control of MAPK and NF-κB signaling pathways [21], [22], [23], [24]. Inactivation of the NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways via YopJ-mediated inhibition of the inhibitor of kappa B kinase beta (IKKβ) and MAPK kinases (MKKs) is critical for apoptosis of Yersinia-infected macrophages [23], [25].

YopJ is the prototypical member of a family of T3SS effectors that inhibit the NF-κB pathway [26], [27], [28]. These proteins exhibit homology to CE cysteine proteases [26]. Evidence has been obtained that YopJ can function as a deubiquitinase [29], [30], [31]. However, more recent studies indicate that YopJ has acetyltransferase activity, acetylating Ser and Thr residues critical for the activation of the MKKs and IKKβ [32], [33], [34]. YopJ is an important virulence factor in Y. pseudotuberculosis [21], [35] and Y. enterocolitica, where it is known as YopP [36].

Recently, it has been determined that caspase-1 can be activated in a T3SS-dependent manner by two distinct pathways in macrophages infected with Yersinia [6]. In one pathway, insertion of channels or pores in the plasma membrane by the T3SS translocon activates caspase-1 and causes pyroptosis in Yersinia-infected macrophages [6], [37], [38], [39]. Activation of caspase-1 in response to the Yersinia T3SS translocon can be counteracted by Yop effectors including YopE [39] and YopK [6], and therefore this pathway is inhibited in macrophages infected with wild-type bacteria.

A second pathway of caspase-1 activation that occurs in macrophages infected with wild-type Yersinia is not inhibited by YopE or YopK and requires YopJ activity [6], [8]. Although caspase-1 is activated in response to YopJ activity, caspase-1 is not required for YopJ-dependent macrophage apoptosis [6], [8]. A potential explanation for the ability of YopJ to cause caspase-1 activation came from the work of Greten et al. [7], who showed that genetic or pharmacological ablation of IKKβ resulted in apoptosis, activation of caspase-1 and secretion of IL-1β from macrophages following stimulation of TLR4 with LPS. Evidence was obtained that an anti-apoptosis gene product expressed under control of NF-κB, plasminogen activator inhibitor 2 (PAI-2), negatively regulates apoptosis and caspase-1 activation in LPS-stimulated macrophages [7]. The authors suggested that inhibition of caspase-1 by the NF-κB pathway represents a negative feedback loop that allows the innate immune system to activate, via TLR4, a compensatory host defense response against Gram-negative pathogens that inhibit activation of NF-κB [7].

Different Yersinia strains display a range of YopJ-dependent apoptotic activities on macrophages [8], [35], [40], [41]. This difference in apoptotic activity is due to the expression of distinct YopJ isoforms by different Yersinia strains [8], [35], [40], [41]. For example, a Y. enterocolitica strain encoding a YopP protein with an Arg at position 143 was shown to have higher apoptotic activity and inhibit IKKβ more efficiently in macrophages then strains having a Ser at this position [40]. Y. pestis KIM, a 2.MED (Mediaevalis) biovar strain, encodes a YopJ isoform that causes higher levels of apoptosis and caspase-1 activation in infected macrophages as compared to other YopJ isoforms [8]. The YopJKIM protein has an Arg at position 143 but in addition has two amino acid substitutions, at positions 177 and 206, as compared to other isoforms of this effector found in Y. pestis or Y. pseudotuberculosis strains.

Here, the molecular basis for the enhanced ability of YopJKIM to cause apoptosis and activate caspase-1 in Yersinia-infected macrophages was studied, with the goal of better understanding the underlying mechanism of this host response. Analysis of YopJKIM in parallel with other YopJ isoforms indicated that the unique capacity of this effector to cause high-level apoptosis and caspase-1 activation requires both codon substitutions at positions 177 and 206. The presence of these codon substitutions also correlated with the enhanced ability of YopJKIM to inhibit MKK and IKKβ signaling pathways. Infection of IKKβ-deficient macrophages with Y. pestis confirmed that this kinase has an important role in negatively regulating caspase-1 activation [7]. Finally, evidence was obtained that K+ efflux leading to activation of the NLRP3/ASC/capsase-1 inflammasome is important for secretion of IL-1β and IL-18 from macrophages infected with Y. pestis KIM. These findings indicate that, by inhibiting production of survival factors under control of the NF-κB and MAPK pathways, YopJ causes TLR4-dependent apoptosis and caspase-1 activation in macrophages infected with Yersinia. In addition, Y. pestis KIM causes high levels of apoptosis and caspase-1 activation in macrophages because it has evolved a YopJ isoform with enhanced inhibitory activity on NF-κB and MAPK pathways.

Results

Identification of amino acid substitutions in YopJ that increase MyD88 - and Trif-dependent caspase-1 activation in Yersinia-infected macrophages

Sequence comparisons were made between YopJKIM and YopJ proteins from two other Yersinia strains that display lower apoptosis activity in macrophages, Y. pseudotuberculosis IP2666 and Y. pestis CO92. There is one amino acid difference between YopJKIM and YopJ in Y. pseudotuberculosis (YopJYPTB), corresponding to L177F in the predicted catalytic core [29] of the enzyme (residues 109-194; Figure S1 in Text S1). Comparison of YopJKIM with YopJ from Y. pestis CO92 (YopJCO92) revealed two differences, L177F and E206K, the latter of which is located just beyond the carboxy-terminal end of the predicted catalytic core (Figure S1 in Text S1).

To determine if the amino acid substitutions at positions 177 and 206 of YopJKIM affect secretion or delivery of the effector into macrophages, expression plasmids encoding YopJKIM, YopJYPTB, or YopJCO92 appended with C-terminal GSK tags were constructed. An expression plasmid encoding a YopJ isoform with a Leu at position 177 and a Lys at position 206 (YopJKIME206K) was also constructed in the same manner. The expression plasmids were introduced into a ΔyopJ mutant of Y. pseudotuberculosis (IP26; Table S1 in Text S1). Y. pseudotuberculosis was used in the experiment because it lacks the Pla protease of Y. pestis which is known to degrade Yops secreted in vitro [42]. The resulting strains were induced to secrete Yops under low calcium growth conditions and immunoblotting of the secreted proteins showed that YopJKIM, YopJYPTB, YopJKIME206K and YopJCO92 were exported at equal levels (Figure S2 in Text S1).

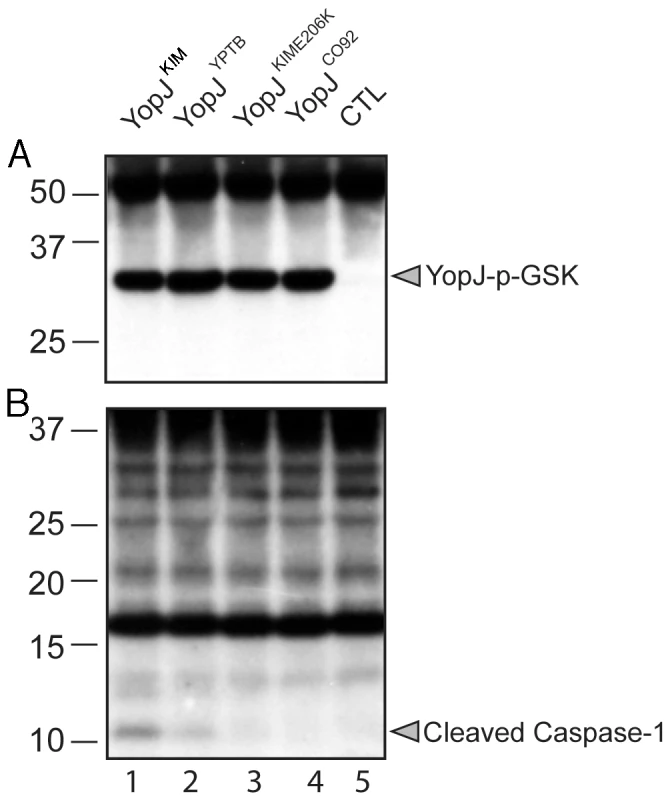

A translocation assay was performed using the phospho-GSK reporter system [43]. IP26 strains expressing the different YopJ isoforms fused to GSK were used to infect bone marrow derived macrophages (BMDMs) for 2 hr. Delivery of the effector into host cells was measured by anti-phospho-GSK immunoblotting [43]. The results showed that YopJKIM, YopJYPTB, YopJKIME206K and YopJCO92 isoforms were translocated at similar levels (Figure 1A). Samples of the same lysates analyzed in Figure 1A were subjected to immunoblotting with anti-caspase-1 antibody to measure the level of caspase-1 cleavage. Consistent with previous results [6], cleavage of caspase-1 was detected in BMDMs infected with Y. pseudotuberculosis expressing YopJYPTB (Figure 1B, lane 2). However, caspase-1 cleavage was comparatively higher with expression of YopJKIM (lane 1) and lower with expression of YopJKIME206K or YopJCO92 isoforms (lanes 3 and 4, respectively). These results suggest that the ability of YopJKIM to trigger maximal caspase-1 activation requires both the F177L and K206E substitutions, and these codon changes impart an activity to the protein that is manifested following its delivery into the host cell.

YopJ-mediated apoptosis in response to Yersinia infection requires stimulation of TLR4 in naïve macrophages to activate a death response pathway [25], [44]. It is not known if TLR signaling is required for YopJ-dependent activation of caspase-1 in Yersinia-infected macrophages. When BMDMs lacking the two major TLR adaptors, MyD88 and Trif, were infected with wild-type Y. pseudotuberculosis IP2666 for 2 hr, activation of caspase-1 was substantially reduced (Figure S3 in Text S1). Cleavage of caspase-1 was not diminished in IP2666-infected BMDMs missing only MyD88 or Trif (data not shown), indicating that TLR signaling through either of these adaptors is important for the downstream events that lead to activation of caspase-1 in conjunction with YopJ activity. YopJ-dependent caspase-1 activation and IL-1β secretion were inhibited when BMDMs were treated with LPS prior to infection with Y. pseudotuberculosis (Figure S3 in Text S1) [6] or Y. pestis [8]. Thus, macrophages pre-stimulated with LPS are desensitized to undergo YopJ-dependent apoptosis [38] and caspase-1 activation upon Yersinia infection. Desensitization occurs because the TLR4 signaling pathway contains a negative feed back mechanism operating via NF-κB that upregulates expression of proteins that inhibit apoptosis and activation of caspase-1 [7].

The F177L and K206E substitutions in YopJKIM are important for increased apoptosis and secretion of IL-1β and IL-18 in Y. pestis-infected macrophages

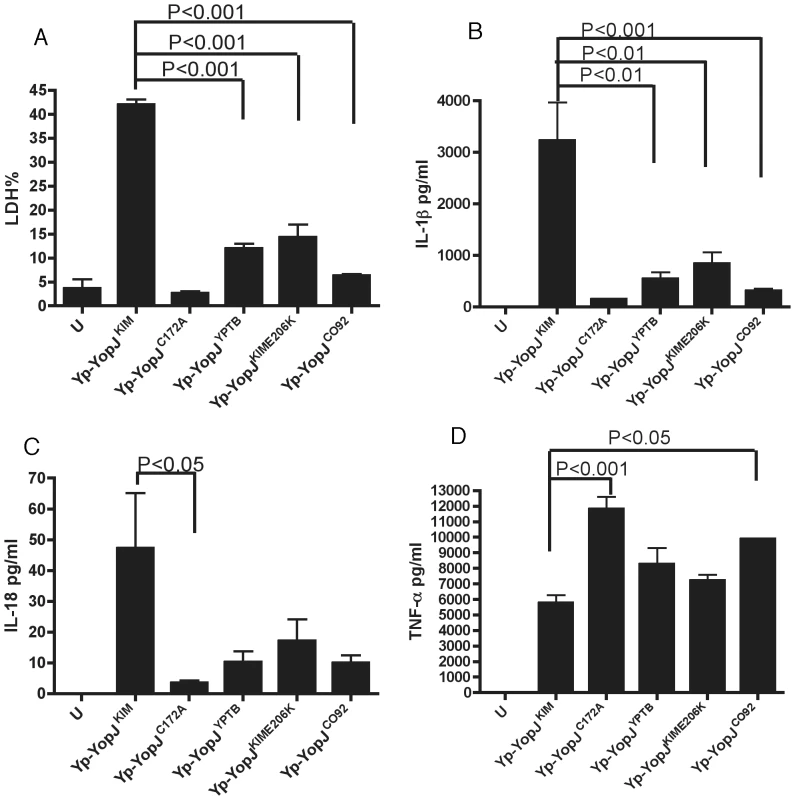

To demonstrate that the polymorphisms in YopJKIM at positions 177 and 206 were important for the activity of this effector in the native context of Y. pestis, a L177F codon change was introduced into the sequence of yopJKIM on the virulence plasmid pCD1 by allelic exchange, converting it to yopJYPTB. In addition, an E206K codon change, a double L177F/E206K codon change, and a C172A codon change were introduced into pCD1, creating yopJKIME206K, yopJC092, and yopJC172A, respectively. The resulting strains (referred to as Yp-YopJYPTB, Yp-YopJKIME206K, Yp-YopJC092 and Yp-YopJC172A)(Table S1 in Text S1) were phenotypically analyzed. As shown by immunoblotting of whole bacterial lysates, YopJKIM, YopJYPTB, YopJKIME206K and YopJCO92 were expressed at equal levels in Y. pestis (Figure S4 in Text S1). The ability of Y. pestis strains expressing the different YopJ isoforms to induce apoptosis and cytokine secretion in BMDMs was then determined after a 24 hr infection. As shown in Figure 2A,B, the amounts of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) released (used as a marker of cell death) and IL-1β secreted were significantly lower in macrophages infected with Yp-YopJYPTB, Yp-YopJKIME206K or Yp-YopJCO92 as compared to Yp-YopJKIM. A similar trend was seen for secretion of IL-18 (Figure 2C).

Caspase-1 was required for the processing and release of IL-1β from macrophages under these infection conditions as shown by infecting wild-type or casp-1-/- BMDMs with Yp-YopJKIM and isolating IL-1β from infection supernatants by immunoprecipitation. Mature IL-1β was absent in supernatants isolated from casp-1-/- BMDMs infected with Yp-YopJKIM (Figure S5 in Text S1), indicating that the processing and release of IL-1β during infection of wild-type macrophages with Yp-YopJKIM occurred in a caspase-1-dependent manner.

As a control, levels of TNF-α, which is secreted independent of caspase-1 activity, were measured. Macrophages infected with Yp-YopJC172A or Yp-YopJCO92 secreted significantly higher levels of TNF-α as compared to Yp-YopJKIM, whereas the other mutants tested produced intermediate results (Figure 2D). Overall, these results indicate that amino acid substitutions at positions 177 and 206 are important for the ability of YopJKIM to induce high levels of macrophage apoptosis, caspase-1 activation and secretion of mature IL-1β and IL-18 in Y. pestis-infected macrophages. Conversely, the amino acid substitutions at positions 177 and 206 are important for the ability of YopJKIM to inhibit TNF-α secretion in macrophages under the same conditions.

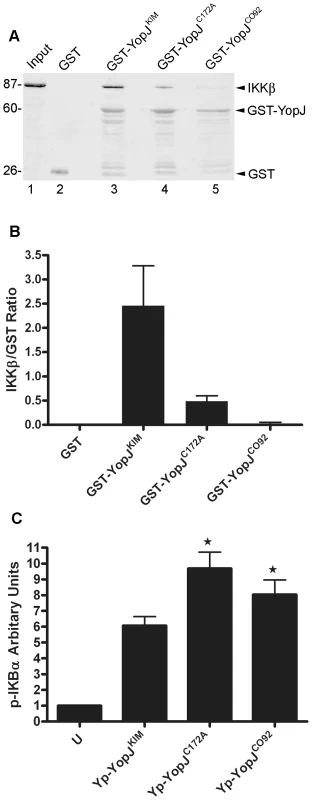

YopJKIM binds to IKKβ with higher affinity and more efficiently inhibits phosphorylation of IκBα as compared to YopJCO92

To determine if YopJKIM has higher affinity for IKKβ as compared to other YopJ isoforms, several different YopJ proteins were assayed for the ability to bind this kinase in cell lysates. Purified GST-YopJ fusion proteins or GST alone bound to beads were incubated in HEK293T cell lysates that contained overexpressed IKKβ. The amounts of IKKβ and GST proteins recovered on the beads after washing was measured by quantitative immunoblotting. IKKβ bound to beads coated with GST-YopJKIM but not to beads coated with GST alone (Figure 3A, compare lanes 2 and 3). There was reduced binding of IKKβ to GST-YopJCO92 as compared to GST-YopJKIM (Figure 3A, compare lanes 3 and 5). When the amount of bound IKKβ was normalized to the amount of GST fusion protein recovered, it was estimated that 10-times less IKKβ bound to GST-YopJCO92 as compared to GST-YopJKIM (Figure 3B). A GST fusion protein encoding YopJC172A bound ∼5 times less IKKβ as compared to GST-YopJKIM (Figure 3A, compare lanes 3 and 4, Figure 3B), suggesting that the catalytic Cys residue contributes to binding between IKKβ and YopJKIM. Overall, these results suggest that YopJKIM has higher affinity for IKKβ as compared to YopJCO92.

To determine if YopJKIM is a better inhibitor of IKKβ than YopJCO92, the amount of phosphorylated IκBα (p-IκBα) in BMDMs was measured after a 1 hr infection. As shown in Figure 3C, significantly lower levels of p-IκBα were present in macrophages infected with Yp-YopJKIM as compared to BMDMs infected with Yp-YopJCO92. In addition, significantly lower levels of p-IκBα were present in macrophages infected with Yp-YopJKIM as compared to BMDMs infected with Yp-YopJC172A (Fig. 3C), confirming that acetyltransferase activity is important for YopJ to inhibit the NF-κB pathway. Because IκBα is directly phosphorylated by IKKβ, these results are consistent with the idea that YopJKIM more efficiently inhibits IKKβ activity as compared to YopJCO92.

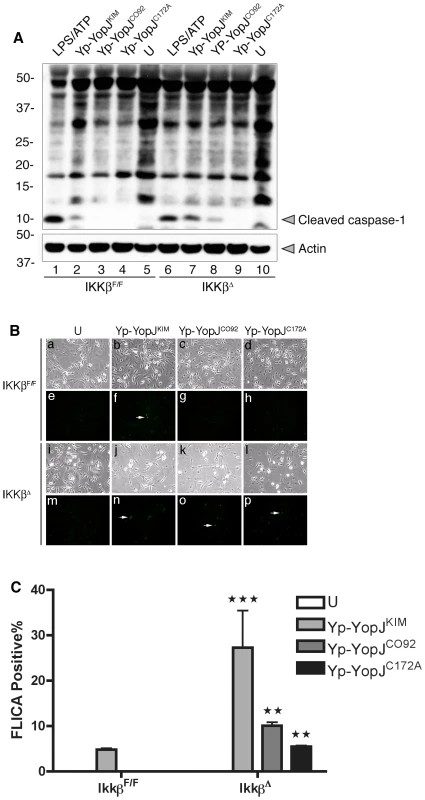

Partial genetic ablation of IKKβ increases caspase-1 activation in Y. pestis-infected macrophages

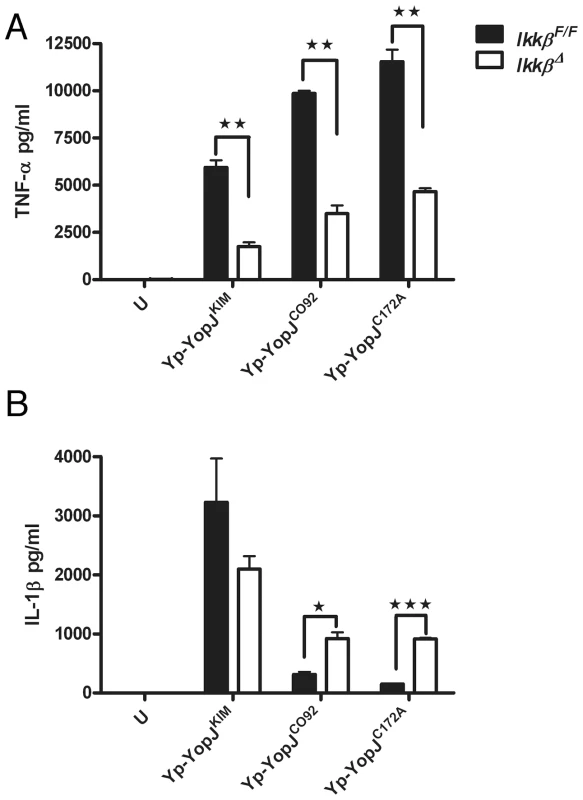

Greten et al. have shown that treatment of IKKβ-deficient macrophages with LPS causes activation of caspase-1 and secretion of IL-1β [7]. If IKKβ activity is important to suppress activation of the inflammasome in macrophages infected with a live Gram-negative pathogen, than increased caspase-1 activation and IL-1β secretion should be observed in IKKβ-deficient as compared to wild-type BMDMs infected with Y. pestis. The effect of genetic inactivation of Ikkβ on caspase-1 activation in Y. pestis-infected macrophages was therefore investigated. IKKβ-deficient BMDMs were generated by conditional Cre-lox-mediated deletion of a “floxed” Ikkβ gene (referred to as IkkβΔ BMDMs; Materials and Methods). The IkkβΔ BMDMs or wild-type control IkkβF/F macrophages were left uninfected or infected with Yp-YopJKIM, Yp-YopJCO92 or Yp-YopJC172A for 4 hr. Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) of Ikkβ message was used to estimate the efficiency of Cre-lox mediated deletion of the Ikkβ gene in the BMDMs. Results indicated that ∼50% of the Ikkβ genes had been deleted in the population of IkkβΔ cells (Figure S6A in Text S1). The impact of this partial deficiency in Ikkβ on the expression and secretion of cytokines in the Y. pestis infected macrophages was determined. As compared to the IkkβF/F macrophages, the IkkβΔ BMDMs were compromised for infection-induced expression of mRNA for the cytokines IL-18, TNFα and IL-1β, as shown by qRT-PCR (Figure S6B–D in Text S1). This result was expected since the NF-κB pathway positively regulates expression the il-18, tnf and il-1b genes. Accordingly, the IkkβΔ BMDMs secreted lower levels of TNFα as compared to IkkβF/F macrophages after a 24 hr infection (Figure 4A). In addition, during infection with Yp-YopJCO92 or Yp-YopJC172A, higher amounts of IL-1β were secreted from IkkβΔ BMDMs as compared to IkkβF/F macrophages (Figure 4B), consistent with the idea that the NF-κB pathway negatively regulates processing and secretion of IL-1β via control of caspase-1 activation [7]. Unexpectedly, the amount of IL-1β secreted following infection with Yp-YopJKIM appeared to be lower in IkkβΔ BMDMs as compared to IkkβF/F macrophages, although the observed difference was not statistically significant (Figure 4B). The interpretation of this latter result was complicated because of the fact that there was only partial deficiency in Ikkβ in the IkkβΔ BMDMs, but one possible explanation was that synthesis of pro-IL-1β was reduced due to the extremely low level il-1b message in the IkkβΔ BMDMs infected with Yp-YopJKIM (Figure S6D in Text S1).

Activation of caspase-1 was measured by immunoblotting to detect the cleaved enzyme in lysates prepared 2 hr after infection of IkkβΔ or IkkβF/F BMDMs with Yp-YopJKIM, Yp-YopJCO92 or Yp-YopJC172A. Caspase-1 activation in uninfected BMDMs or in macrophages treated with LPS and ATP was determined in parallel for comparison. Increased caspase-1 cleavage occured in IkkβΔ macrophages infected with Yp-YopJKIM or Yp-YopJCO92 as compared to IkkβF/F BMDMs infected with the same strains (Figure 5A, compare lanes 7 and 8 with 2 and 3). Cleaved caspase-1 was below the limit of detection in IkkβΔ macrophages infected with Yp-YopJC172A (Figure 5A, lane 9). Activation of caspase-1 was also measured by a microscopic assay utilizing FAM-YVAD-FMK, a fluorescent probe for active caspase-1, in IkkβΔ or IkkβF/F BMDMs infected for 9 hr. The results showed overall higher levels of caspase-1 positive cells in IkkβΔ as compared to IkkβF/F macrophages (Figure 5B and C). Taken together, these results show that loss of IKKβ activity can increase caspase-1 activation in macrophages infected with Y. pestis, and are consistent with the idea that IKKβ is an important target of YopJ for activation of the inflammasome.

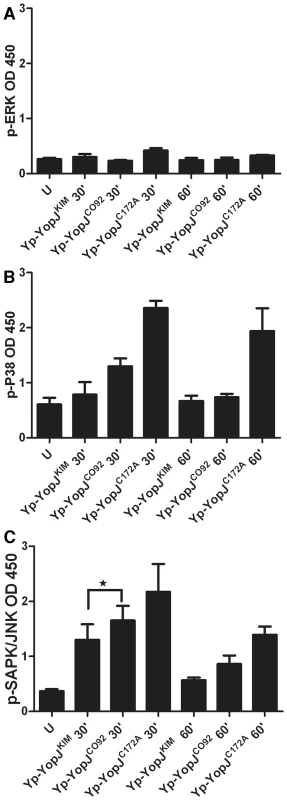

YopJKIM more efficiently inhibits activation of MAPKs as compared to YopJCO92

In addition to binding to and acetylating IKKβ, YopJ binds to and acetylates other members of the MKK superfamily including MKK1, MKK2, MKK3, MKK4, MKK5, and MKK6 [26], [32], [33]. There is evidence that YopJ binds to a site conserved on members of the MKK-IKK superfamily [45]. Since we had previously obtained evidence that inhibition of MAPK signaling was critical for YopJ-induced macrophage apoptosis [23], we sought to determine if YopJKIM could more efficiently inhibit MAPK phosphorylation as compared to YopJCO92. BMDMs were left uninfected or infected for 30 or 60 min with Yp-YopJKIM, Yp-YopJCO92, or Yp-YopJC172A and ELISA was used to measure phosphorylation of the MAPKs ERK (substrate of MKK1/2), p38 (substrate of MKK3/6) and SAPK/JNK (substrate of MKK4/7) (Materials and Methods). As shown in Figure 6A, ERK was not phosphorylated to a large degree at either time point in macrophages infected with Yp-YopJC172A and therefore it was not possible to evaluate the degree to which ERK phosphorylation was inhibited by either YopJKIM or Yp-YopJCO92. In contrast, p38 and JNK did show increased phosphorylation upon infection with Yp-YopJC172A, especially at the 30 min time point (Figure 6B and C, respectively). There was in general reduced phosphorylation of p38 and JNK in BMDMs infected with Yp-YopJKIM as compared to YopJCO92, especially at the 30 min time point, and the difference was statistically significant in the case of JNK (Figure 6B and C). These results suggest that YopJKIM more efficiently inhibits the activities of MKK3/6 and MKK4/7 as compared to YopJCO92.

The NLRP3/ASC/caspase-1 inflammasome is important for secretion of IL-1β and IL-18 from macrophages infected with Yp-YopJKIM

The importance of several different inflammasome components for Y. pestis-induced secretion of IL-1β and IL-18 was investigated using NLRP3 (Nlrp3-/-)-, ASC (Asc-/-) - or NLRC4 (Nlrc4-/-)-deficient BMDMs. The mutant BMDMs or wild-type control macrophages were infected with Yp-YopJKIM or Yp-YopJC172A. Tissue culture supernatants were collected and analyzed by ELISA to measure the levels of IL-1β and IL-18 present after 24 hr of infection. NLRP3 - or ASC-deficient BMDMs infected with Yp-YopJKIM secreted significantly lower levels of IL-1β and IL-18 as compared to wild-type macrophages infected with Yp-YopJKIM (Figure 7A,B; Figure S7A, B in Text S1). NLRC4-deficient macrophages released similar levels of these cytokines as compared to wild-type BMDMs (Figure 7A, Figure S7A in Text S1), suggesting that NLRC4 does not play a significant role in caspase-1 activation and cytokine secretion during Yp-YopJKIM infection. Both Yp-YopJKIM and Yp-YopJC172A stimulated infected BMDMs to secrete TNF-α, although higher levels (∼2 to 3 fold) of TNF-α were secreted from macrophages infected with Yp-YopJC172A regardless of macrophage type infected (Figure 7C, D). Thus, NLRP3 and ASC, but not NLRC4, are involved in the secretion of IL-1β and IL-18, but not TNF-α, from Yp-YopJKIM -infected macrophages.

YopJKIM-induced macrophage apoptosis does not require NLRP3, ASC or NLRC4

To determine if NLRP3, NLRC4 or ASC play a role in YopJKIM-dependent apoptosis, wild-type BMDMs or BMDMs deficient for these inflammasome components were left uninfected or infected with Yp-YopJKIM or Yp-YopJC172A. Tissue culture supernatants were collected 24 hr post-infection and analyzed for LDH. Similar levels of LDH were released from NLRP3, NLRC4 or ASC-deficient BMDMs as compared wild-type macrophages after Yp-YopJKIM infection (Figure 7E, F). Low levels of LDH release occurred in all macrophages infected with Yp-YopJC172A. These results demonstrate that apoptosis can occur in Yp-YopJKIM -infected macrophages in the absence of NLRP3, NLRC4 or ASC, consistent with our previous data showing that macrophage apoptosis during Yp-YopJKIM infection is independent of caspase-1 [8].

Evidence that K+ efflux is important for secretion of IL-1β and IL-18 from macrophages infected with Yp-YopJKIM

Efflux of intracellular K+ has been implicated in the activation of the NLRP3/ASC/caspase-1 inflammasome [10], [11], [12]. To assess a role for intracellular K+ efflux in caspase-1 activation and IL-1β release during infection with Y. pestis, BMDMs were infected with Yp-YopJKIM or Yp-YopJC172A, and then incubated in cell culture media supplemented with 30 mM KCl, 30 mM NaCl or no supplement. Cell culture supernatants were collected at 8 hr and 24 hr time points and analyzed for the presence of IL-1β and TNF-α by ELISA. Significantly lower levels of IL-1β (∼5-fold) were secreted from macrophages infected with Yp-YopJKIM in the presence of 30 mM KCl as compared to untreated macrophages at 8 hr post-infection (Figure 8A). Macrophages infected with Yp-YopJKIM in the presence of 30 mM NaCl appeared to secrete IL-1β to slightly lower levels as compared to untreated infected macrophages at 8 hr post-infection, but this difference was not significant (Figure 8A). A similar trend of IL-1β secretion was observed at the 24 hr time point when macrophages were infected with Yp-YopJKIM in the presence or absence of KCl or NaCl (Figure 8C). Macrophages infected with Yp-YopJC172A secreted similar low levels of IL-1β regardless of treatment (Figure 8A, C). Secretion of TNF-α from Yp-YopJKIM - or Yp-YopJC172A-infected macrophages was not affected by the presence of 30 mM KCl or NaCl (Figure 8B, D). In addition, the presence of 30 mM KCl did not diminish LDH release from BMDMs infected with Yp-YopJKIM (data not shown). BMDMs deficient for the purinergic receptor, P2X7, secreted similar levels of IL-1β and IL-18 as did wild-type macrophages infected with Yp-YopJKIM, indicating that this receptor does not play a significant role in inducing the secretion of these cytokines (data not shown). Taken together, these results suggest that a K+ efflux that occurs independent of P2X7R is important for activation of the NLRP3/ASC/caspase-1 inflammasome in macrophages infected with Yp-YopJKIM.

To examine how Y. pestis infection and KCl treatment affected steady state levels of pro-IL-1β, lysates of macrophages left untreated or treated with KCl or NaCl were prepared at 8 hr post-infection and analyzed by immunoblotting for pro-IL-1β or actin as a loading control. As shown in Figure 8E, infection stimulated production of pro-IL-1β, with steady state levels of pro-IL-1β slightly lower in macrophages infected with Yp-YopJKIM as compared to Yp-YopJC172A (compare lanes 2 and 3, 5 and 6 and 8 and 9). Similar amounts of pro-IL-1β were detected in macrophages infected with Yp-YopJKIM in the absence or presence of 30 mM KCl or 30 mM NaCl (Figure 8E, compare lane 2 with 5 and 8). These results indicated that reduced detection of IL-1β in supernatants of macrophages infected with YopJKIM and treated with exogenous KCl was not due to KCl inhibiting production of pro-IL-1β.

Discussion

It was previously shown that caspase-1 was activated during YopJ-induced apoptosis of macrophages infected with Y. pseudotuberculosis [6]. In addition, it was demonstrated that YopJKIM had increased capacity to cause macrophage apoptosis and activate caspase-1 as compared to other YopJ isoforms [8]. However, the mechanism of YopJ-induced caspase-1 activation and the molecular basis for enhanced apoptosis and activation of caspase-1 in macrophages by YopJKIM was unknown. The results of studies reported here indicate that several of the requirements for YopJ-induced apoptosis and caspase-1 activation are the same, and therefore it is likely that these two processes are mechanistically connected. First, it is known that TLR4 signaling is important for YopJ-induced macrophage apoptosis [21], [22], [23], [24] and we show here that the two major TLR adaptors, MyD88 and Trif, are important for YopJ-induced caspase-1 activation. Second, desensitization of macrophages by pretreatment with LPS decreases YopJ-induced apoptosis [38] and caspase-1 activation. Third, comparison of the activities of different YopJ isoforms showed a direct correlation between apoptosis, caspase-1 activation and inhibition of MAPK and NF-κB signaling pathways. Forth, when macrophages in which Ikkβ was conditionally deleted were infected with Y. pestis, caspase-1 activation increased, providing genetic evidence that IKKβ is an important target of YopJ for caspase-1 activation, as well as apoptosis [25].

Inhibition of MAPK and NF-κB pathways by YopJ is thought to reduce expression of survival factors (e.g. FLIP, XIAP), thereby potentiating TLR4 signaling to trigger apoptosis [22], [23], [24]. Inactivation of the MAPK and NF-κB pathways by YopJ could also prevent expression of putative negative regulators of caspase-1 (e.g. PAI-2) [7]. It is important to point out that there is no direct evidence that PAI-2 inhibits caspase-1 activation independently of blocking apoptosis, rather the data show that PAI-2 overexpression reduces both apoptosis and caspase-1 activation [7]. It is possible that PAI-2 inhibits apoptosis and that events triggered downstream of TLR4-dependent programmed cell death are required for caspase-1 activation. We suggest that caspase-1 activation is a normal outcome of a type of apoptosis that is triggered in naïve macrophages by TLR4 signaling combined with pathogen interference with MAPK and NF-κB pathways.

Data presented here suggest that YopJKIM triggers increased apoptosis and caspase-1 activation because it is a better inhibitor of macrophage survival pathways than other YopJ isoforms. YopJKIM could function as a better inhibitor of macrophage signaling pathways if it had a longer half-life in the host cell, or had higher affinity for substrates. The F177L polymorphism could increase protein stability, although it is not immediately clear why a Leu at position 177 rather than a Phe would increase protein half-life. The K206E mutation could increase half-life, which is reasonable since Lys residues can be subject to ubiquitination. Although not mutually exclusive of the preceding ideas, we favor the hypothesis that the F177L and K206E substitutions allow YopJKIM to bind more tightly to substrates, thereby making acetylation of targets more efficient at limiting enzyme concentrations. We obtained two pieces of evidence supporting this hypothesis. First, YopJKIM had higher apparent affinity for IKKβ than YopJCO92 when these interactions were measured in cell lysates by a GST pull down assay. Second, macrophages infected with Yp-YopJKIM had lower levels of phosphorylated IκBα and MAPKs as compared to macrophages infected with Yp-YopJCO92, indicating that there was increased inhibition of IKKβ and MAPK kinase activity by Yp-YopJKIM.

The results suggest a model whereby the canonical yopJ allele in Y. pseudotuberculosis (yopJYPTB) was inherited by an ancestral Y. pestis strain, from which it evolved to encode an isoform with higher apoptotic and caspase-1-activating potential, YopJKIM, by the F177L mutation. The predicted sequence of a YopJ protein in Y. pestis biovar 2.MED strain K1973002 (ZP_02318615) is identical to the sequence of YopJKIM, suggesting that the phenotype observed is not an artifact resulting from a mutation acquired during laboratory passage, but is associated with a unique yopJ genotype associated with 2.MED strains. It is also hypothesize that the yopJCO92 allele evolved from yopJYPTB to encode an isoform with lower cytotoxic and caspase-1 activating potential (YopJCO92) by the E206K codon substitution. How these polymorphisms in YopJ affect Y. pestis virulence and or the host response is not known but is an important question to address in future studies.

The importance of different inflammasome components for YopJ-dependent activation of caspase-1 in macrophages infected with Y. pseudotuberculosis has recently been examined [6]. This study showed that NLRP3 and ASC were not required for activation of caspase-1 as measured by immunoblot analysis of caspase-1 cleavage [6]. Those results would appear to be in conflict with findings presented here showing a role for NLRP3 and ASC in secretion of IL-1β and IL-18 from macrophages infected with Yp-YopJKIM. However, recent studies suggest that multiple distinct caspase-1 activation pathways with different biological outcomes can operate in macrophages infected with a bacterial pathogen. For example, evidence has been obtained that Legionella pneumophila stimulates two distinct pathways of caspase-1 activation in macrophages [46]. ASC is required for secretion of active IL-18 from L. pneumophila-infected macrophages, but is not required for caspase-1 dependent induction of pyroptosis [46]. In addition, the multiplicity and temporal stage of infection of macrophages with a bacterial pathogen can affect the requirements for cell death and activation of caspase-1. Shigella flexneri infection of macrophages at low MOI (<10) for short periods of time induces NLRC4-dependent pyroptosis [47], [48], while infection at higher MOI (50) for longer time periods induces NLRP3-dependent pyronecrosis [48]. Two different infection procedures for examining YopJ-induced caspase-1 activation in macrophages have been used in this study and previous publications [6], [8]. A high MOI (20) followed by 1 hr of bacterial-host cell contact before addition of gentamicin results in detectable YopJ-dependent apoptosis and caspase-1 activation within 2 hr of infection (Figure 5A, Figure S3 in Text S1) [6] but no detectable secretion of IL-1β by this time point (data not shown) [6] . A low MOI (10) followed by 20 min of bacterial-host cell contact before addition of gentamicin results in detectable apoptosis and caspase-1 activation by 8–9 hr (Figure 5B,C) [8], at which time secreted IL-1β and IL-18 are first detected [8]. High amounts of secreted IL-1β and IL-18 are detected at 24 hr post infection under the low MOI procedure (e.g. Figure 2) [8]. The high and low MOI infection procedures may result in different requirements for NLRs to activate caspase-1, as shown by a requirement for ASC and NLRP3 in the latter but not former method. Interestingly, the low MOI procedure appears to slow down the kinetics of apoptosis and caspase-1 activation, which is likely important to allow for synthesis of NLRP3 [19] and the pro-forms of IL-1β and IL-18.

Under the low MOI conditions the presence of 30 mM KCl in the infection medium inhibited the secretion of IL-1β and IL-18 from macrophages infected with Yp-YopJKIM, suggesting an important role for K+ efflux in caspase-1 activation. Efflux of intracellular K+ mediated by the P2X7R is critical for ATP-induced caspase-1 activation in macrophages primed with LPS [49]. However, like other NLRP3 activators such as nigericin, caspase-1 activation in response to Yp-YopJKIM infection did not require P2X7R. One possibility is that pore formation during YopJKIM-induced apoptosis leads to K+ efflux, resulting in activation of the NALP3/ASC/caspase-1 inflammasome. One limitation of this model is that it remains to be determined if K+ efflux acts as a proximal activating signal of the NALP3/ASC/caspase-1 inflammasome. A second limitation of this model is that apoptosis is generally associated with maintenance of an intact plasma membrane, until late stages of cell death [4]. Future experiments will need to address the possibility that YopJ-induced apoptosis of Yersinia-infected macrophages can be associated with rapid membrane permeability, resulting in K+ efflux and caspase-1 activation.

Materials and Methods

Ethics statement

All animal use procedures were conducted following the NIG Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and performed in accordance with Institutional regulations after review and approval by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Stony Brook University.

Yersinia strains, plasmids and growth conditions

Y. pestis and Y. pseudotuberculosis strains used in this study are listed in Table S1 in Text S1. Y. pestis strains used in this study are derived from KIM5 [8], which lacks the pigmentation locus (pgm) and are exempt from select agent guidelines and conditionally attenuated. Introduction of codon changes into yopJ in KIM5 (Table S1 in Text S1) was performed using the suicide plasmid pSB890 and allelic exchange as described [50]. The arabinose inducible plasmid encoding YopJKIM (pYopJ-GSK) has been described [43]). Codon changes were introduced into yopJKIM on this plasmid using Quikchange (Invitrogen), yielding pYopJYPTB-GSK, pYopJKIME206K-GSK, and pYopJCO92-GSK. The resulting plasmids were used to transform IP26 (IP2666 ΔyopJ) using electroporation and selection on LB agar plates containing ampicillin (100 µg/ml) [8].

Bone marrow macrophage isolation and culture conditions

Bone marrow derived macrophages (BMDM) were isolated from the femurs of 6 - to 8-week-old C57BL/6 female mice (Jackson Laboratories), Casp-1-/- mice [8], P2X7 receptor-deficient mice [51], Ikkβf/f or Ikkβf/f;MLysCre mice [52], [53], NLRC4 - (Nlrc4-/-), ASC - (Asc-/-) or NLRP3 - (Nlrp3-/-) deficient mice [54], and MyD88-, Trif - and MyD88/Trif-deficient mice [55] and cultured as previously described [56], [57].

Macrophage infections for LDH release, cytokine ELISA, IL-1β immunoblotting and FLICA

Y. pestis cultures were grown overnight with aeration in HI broth at 28°C. The next day the cultures were diluted to an OD600 of 0.1 in the same medium supplemented with 2.5 mM CaCl2 and incubated for 2 hr at 37°C with aeration. Twenty-four hours before infection, BMDM were seeded into wells of 24-well plates at a density of 1.5×105 cells/ml. Macrophage infections were performed in 37°C incubators with 5% CO2 at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10 as previously described [8]. After addition of bacteria, plates were centrifuged for 5 minutes at 95 xg to induce contact between bacteria and macrophages. After incubation at 37°C for 15 minutes, macrophages were washed once with pre-warmed PBS to remove any bacteria that have not been taken up. Fresh infection medium containing 8 µg/ml of gentamicin was added for 1 hr at 37°C. After 1 hr, macrophages were washed once with PBS and a lower concentration of gentamicin (4.5 µg/ml) in fresh tissue culture media was added for the remaining incubation times. To inhibit potassium efflux from infected macrophages, potassium chloride (KCl) was added to a final concentration of 30 mM concurrently with the media exchanges containing 8 µg/ml gentamicin and 4.5 µg/ml gentamicin [8]. Sodium chloride (NaCl) was used as a control and added as above at a concentration of 30 mM above baseline. Amounts of IL-1β, TNF-α or IL-18 secreted into tissue culture media during infection assays were measured by ELISA as described [8]. Supernatants from infected macrophages were collected and analyzed for LDH release as described [8]. Staining with 6-carboxyfluorescein–YVAD–fluoromethylketone (FAM-YVAD-FMK; fluorescent inhibitor of apoptosis (FLICA)) (Immunochemistry Technologies) to detect active caspase-1 in infected macrophages was performed using fluorescence and phase microscopy as described [8] with the exception that the procedure was performed 9 hr post-infection, and the anti-Yersinia immunolabeling step was omitted. Quantification of percent caspase-1 positive BMDMs was performed by scoring macrophages for positive signal in three different randomly selected fields (∼50–100 cells per field) on a coverslip.

Immunoblotting for pro-IL-1β

At 8 hr post-infection, macrophage lysates from triplicate wells were collected in 100 µl of 1X lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 5 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mM DTT and a protease inhibitor cocktail [Complete Mini, EDTA-Free, Roche]). Proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. To detect IL-1β, membranes were blotted with goat anti-IL-1β (R&D Systems). A secondary antibody, Hamster anti-goat IRDye 700 antibody (Rockland) was used to detect samples, and blots were viewed on the Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (LI-COR). To control for loading, blots were probed with a rabbit anti-actin antibody (Sigma-Aldrich).

Phospho-IκBα ELISA

BMDMs (106 cells per well) were seeded in 6-well plates. Y. pestis cultures were grown as above and used to infect BMDM at a MOI of 50. 1 hr post infection, cells were washed with ice-cold PBS and incubated in 150 ul of 1X Lysis Buffer (Cell Signaling) for 5 min. Cells were scraped on ice and sonicated twice for 5 seconds each. Lysates were centrifuged at 4°C for 10 min and 100 µl of supernatant was used for ELISA. Phospho-IκBα levels were determined using a PathScan Phospho-IkappaB-alpha (Ser32) Sandwich ELISA kit according to manufacturer's protocol (Cell Signaling).

Macrophage infections for Phospho-MAPK ELISA

BMDMs (106 cells per well) were seeded in 6-well plates. Y. pestis cultures were grown in HI at 28°C overnight and diluted 1∶20 next day in the same medium supplemented with 20 mM NaOX and 20 mM MgCl2. Cultures were shaken at 28°C for 1 hr and switched to 37°C for 2 hr. Cells were infected at an MOI of 20 and incubated for 30 or 60 min without adding gentamicin. Macrophages were harvested and lysed as above. The PathScan MAP Kinase Multi-Target Sandwich ELISA kit was used to determine phosphor-ERK, -p38 and –JNK levels according to manufacturer's instruction (Cell Signaling).

Macrophage infections for YopJ translocation and caspase-1 cleavage assays

Y. pseudotuberculosis strains were grown in 2xYT at 26°C overnight and diluted 1∶40 in the same medium supplemented with 20 mM NaOX, and 20 mM MgCl2. Cultures were shaken at 26°C for 1 hr and shifted to 37°C for 2 hr. BMDMs were seeded into wells of 6-well plates at a density of 106 cells/well. Bacteria were harvested, washed with DMEM and added to BMDMs at an MOI of 20. After 1 hr of infection gentamicin was added to a final concentration of 100 µg/ml. To induce expression of YopJ-GSK proteins, arabinose (0.2%) was maintained during grown in 2xYT at 37°C and in the cell culture medium used for infection. Y. pestis strains were grown and used to infect macrophages as above except that HI broth was used and arabinose was omitted. Two hr post-infection, infected BMDMs were washed with PBS and lysed in buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 5 mM EDTA, 2% Triton X-100, and 0.02% sodium azide with protease inhibitors. In some experiments the macrophages were incubated with 50 ng/ml of LPS for 3 hrs and then exposed to ATP at final concentration of 2.5 mM for 1 hr as a positive control for caspase-1 cleavage. Proteins were resolved by 10% SDS-PAGE, transferred to a PVDF membrane and probed with anti-phospho-GSK-3β primary antibody (Cell Signaling). In some experiments the blots were stripped and re-probed with rabbit polyclonal anti-caspase-1 antibodies (Santa Cruz) or directly developed with this antibody. As a loading control blots were reprobed with an anti-actin antibody (Sigma-Aldrich, clone AC15). Goat anti-rabbit HRP conjugated secondary antibody was used. Blots were detected with ECL reagent (Perkin Elmer Life Sciences, Inc.).

GST pull down assay of YopJKIM-IKKβ interaction

Plasmids for expression of GST-YopJ fusion proteins were constructed from pLP16 [58]. The pLP16 vector was derived from pGEX-2T and codes for YopJYPTB with an N-terminal glutathione-S transferase (GST) affinity tag and a C-terminal M45 epitope tag. Quikchange mutagenesis (Invitrogen) was used to introduce codon changes into pLP16 to generate pGEX-2T-YopJKIM, pGEX-2T-YopJKIMC172A and pGEX-2T-YopJCO92, which encode GST-YopJKIM, GST-YopJC172A and GST-YopJCO92, respectively. The plasmids pGEX-2T, pGEX-2T-YopJKIM, pGEX-2T-YopJKIMC172A and pGEX-2T-YopJCO92 were used to transform E. coli TUNER cells (Novagen). Cultures of TUNER cells harboring the above plasmids were grown in LB at 37°C to OD600 of 0.2. IPTG was added to 0.1 mM final concentration and cultures were grown at 18°C with shaking for 4 hrs. The bacterial pellet obtained from 40 ml of each culture was resuspended in PBS supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche) and sonicated on ice. The solubility of proteins in the sonicates was increased by incubation in the presence of a buffer containing 10% sarkosyl at 4°C overnight [59]. After centrifugation, the supernatant of the bacterial lysate was diluted 5 times with a buffer containing 4% Triton X-100 and 40 mM CHAPS at final concentrations. Thirty µl of glutathione beads (GST Bind Kit, Novagen) were added and the mixture was shaken at 4°C for 1 hr. Beads were washed 4 times with 1 ml of GST Bind Kit buffer and used for pull down assays.

Cell lysates containing overexpressed IKKβ were prepared from HEK293T cells tranfected with a retroviral construct (pCLXSN-IKKβ-IRES-GFP) [25]. HEK293T cells were seeded in 10 cm dishes and grown to reach 70% confluence. The culture medium was replaced with serum free DMEM and the HEK293T cells in each dish were transfected with 10 µg of pCLXSN-IKKβ-IRES-GFP using a calcium phosphate method. Six hrs post transfection, the culture medium was replaced with DMEM containing 10% FBS. Cells were harvested 48 hrs post transfection, sonicated in PBS and centrifuged. Supernatants were stored at −80°C until use.

Beads containing bound GST proteins were incubated with 250 µl of cell lysate supernatants from transfected HEK293T supernatant for 4 hrs at 4°C with constant rotation. The beads were then washed 4 times with 1 ml of PBS each and proteins bound to the beads were eluted in boiling 2X Laemmli sample buffer. Samples of the eluates were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting. Rabbit polyclonal anti-IKKβ antibodies and mouse monoclonal anti-GST antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling and Santa Cruz, respectively. Immunoblot signals representing IKKβ and GST or GST fusion proteins were quantified using an Odyssey imaging system.

Statistical analysis

Experimental data analyzed for significance (GraphPad Prism 4.0) were performed three independent times. Probability (P) values for multiple comparisons of cytokine, phospho-IκBα ELISA and LDH release data were calculated by one-way ANOVA and Tukey's multiple comparisons post-test. P values for two group comparisons of cytokine, phospho-IκBα, and phospho-MAPK ELISA were calculated by two-tailed paired student t test. P values were considered significant if less than 0.05.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. GalanJEWolf-WatzH

2006

Protein delivery into eukaryotic cells by type III secretion

machines.

Nature

444

567

573

2. CornelisGR

2006

The type III secretion injectisome.

Nat Rev Microbiol

4

811

825

3. NavarreWWZychlinskyA

2000

Pathogen-induced apoptosis of macrophages: a common end for

different pathogenic strategies.

Cell Microbiol

2

265

273

4. FinkSLCooksonBT

2005

Apoptosis, pyroptosis, and necrosis: mechanistic description of

dead and dying eukaryotic cells.

Infect Immun

73

1907

1916

5. BergsbakenTFinkSLCooksonBT

2009

Pyroptosis: host cell death and inflammation.

Nat Rev Microbiol

7

99

109

6. BrodskyIEPalmNWSadanandSRyndakMBSutterwalaFS

2010

A Yersinia effector protein promotes virulence by preventing

inflammasome recognition of the type III secretion system.

Cell Host Microbe

7

376

387

7. GretenFRArkanMCBollrathJHsuLCGoodeJ

2007

NF-kappaB is a negative regulator of IL-1beta secretion as

revealed by genetic and pharmacological inhibition of

IKKbeta.

Cell

130

918

931

8. LiloSZhengYBliskaJB

2008

Caspase-1 activation in macrophages infected with Yersinia pestis

KIM requires the type III secretion system effector YopJ.

Infect Immun

76

3911

3923

9. MartinonFTschoppJ

2007

Inflammatory caspases and inflammasomes: master switches of

inflammation.

Cell Death Differ

14

10

22

10. LamkanfiMKannegantiTDFranchiLNunezG

2007

Caspase-1 inflammasomes in infection and

inflammation.

J Leukoc Biol

82

220

225

11. MariathasanSMonackDM

2007

Inflammasome adaptors and sensors: intracellular regulators of

infection and inflammation.

Nat Rev Immunol

7

31

40

12. MartinonFMayorATschoppJ

2009

The inflammasomes: guardians of the body.

Annu Rev Immunol

27

229

265

13. MiaoEALeafIATreutingPMMaoDPDorsM

2010

Caspase-1-induced pyroptosis is an innate immune effector

mechanism against intracellular bacteria.

Nat Immunol

11

1136

1142

14. KannegantiTDLamkanfiMNunezG

2007

Intracellular NOD-like receptors in host defense and

disease.

Immunity

27

549

559

15. SunYHRolanHGTsolisRM

2007

Injection of flagellin into the host cell cytosol by Salmonella

enterica serotype Typhimurium.

J Biol Chem

282

33897

33901

16. MiaoEAAlpuche-ArandaCMDorsMClarkAEBaderMW

2006

Cytoplasmic flagellin activates caspase-1 and secretion of

interleukin 1beta via Ipaf.

Nat Immunol

7

569

575

17. LightfieldKLPerssonJBrubakerSWWitteCEvon MoltkeJ

2008

Critical function for Naip5 in inflammasome activation by a

conserved carboxy-terminal domain of flagellin.

Nat Immunol

9

1171

1178

18. VanceREIsbergRRPortnoyDA

2009

Patterns of pathogenesis: discrimination of pathogenic and

nonpathogenic microbes by the innate immune system.

Cell Host Microbe

6

10

21

19. BauernfeindFGHorvathGStutzAAlnemriESMacDonaldK

2009

Cutting edge: NF-kappaB activating pattern recognition and

cytokine receptors license NLRP3 inflammasome activation by regulating NLRP3

expression.

J Immunol

183

787

791

20. ViboudGIBliskaJB

2005

Yersinia outer proteins: role in modulation of

host cell signaling responses and pathogenesis.

Annu Rev Microbiol

59

69

89

21. MonackDMMecsasJBouleyDFalkowS

1998

Yersinia-induced apoptosis in vivo aids in the

establishment of a systemic infection of mice.

J Exp Med

188

2127

2137

22. ZhangYBliskaJB

2005

Role of macrophage apoptosis in the pathogenesis of

Yersinia.

Curr Top Microbiol Immunol

289

151

173

23. ZhangYTingATMarcuKBBliskaJB

2005

Inhibition of MAPK and NF-kappa B pathways is necessary for rapid

apoptosis in macrophages infected with

Yersinia.

J Immunol

174

7939

7949

24. RuckdeschelKPfaffingerGHaaseRSingAWeighardtH

2004

Signaling of apoptosis through TLRs critically involves toll/IL-1

receptor domain-containing adapter inducing IFN-beta, but not MyD88, in

bacteria-infected murine macrophages.

J Immunol

173

3320

3328

25. ZhangYBliskaJB

2003

Role of Toll-like receptor signaling in the apoptotic response of

macrophages to Yersinia infection.

Infect Immun

71

1513

1519

26. OrthK

2002

Function of the Yersinia effector

YopJ.

Curr Opin Microbiol

5

38

43

27. NeishAS

2004

Bacterial inhibition of eukaryotic pro-inflammatory

pathways.

Immunol Res

29

175

186

28. FehrDCasanovaCLivermanABlazkovaHOrthK

2006

AopP, a type III effector protein of Aeromonas salmonicida,

inhibits the NF-kappaB signalling pathway.

Microbiology

152

2809

2818

29. OrthKXuZMudgettMBBaoZQPalmerLE

2000

Disruption of signaling by Yersinia effector

YopJ, a ubiquitin-like protein protease.

Science

290

1594

1597

30. ZhouHMonackDMKayagakiNWertzIYinJ

2005

Yersinia virulence factor YopJ acts as a deubiquitinase to

inhibit NF-kappa B activation.

J Exp Med

202

1327

1332

31. SweetCRConlonJGolenbockDTGoguenJSilvermanN

2007

YopJ targets TRAF proteins to inhibit TLR-mediated NF-kappaB,

MAPK and IRF3 signal transduction.

Cell Microbiol

9

2700

2715

32. MukherjeeSKeitanyGLiYWangYBallHL

2006

Yersinia YopJ acetylates and inhibits kinase activation by

blocking phosphorylation.

Science

312

1211

1214

33. MittalRPeak-ChewSYMcMahonHT

2006

Acetylation of MEK2 and I kappa B kinase (IKK) activation loop

residues by YopJ inhibits signaling.

Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A

103

18574

18579

34. MittalRPeak-ChewSYSadeRSVallisYMcMahonHT

2010

The acetyltransferase activity of the bacterial toxin YopJ of

Yersinia is activated by eukaryotic host cell inositol

hexakisphosphate.

J Biol Chem

285

19927

19934

35. BrodskyIEMedzhitovR

2008

Reduced secretion of YopJ by Yersinia limits in vivo cell death

but enhances bacterial virulence.

PLoS Pathog

4

e1000067

36. TrulzschKSporlederTIgweEIRussmannHHeesemannJ

2004

Contribution of the major secreted yops of Yersinia

enterocolitica O:8 to pathogenicity in the mouse infection

model.

Infect Immun

72

5227

5234

37. ShinHCornelisGR

2007

Type III secretion translocation pores of Yersinia enterocolitica

trigger maturation and release of pro-inflammatory IL-1beta.

Cell Microbiol

9

2893

2902

38. BergsbakenTCooksonBT

2007

Macrophage Activation Redirects

Yersinia-Infected Host Cell Death from Apoptosis to

Caspase-1-Dependent Pyroptosis.

PLoS Pathog

3

e161

39. SchottePDeneckerGVan Den BroekeAVandenabeelePCornelisGR

2004

Targeting Rac1 by the Yersinia effector protein

YopE inhibits caspase-1-mediated maturation and release of

interleukin-1beta.

J Biol Chem

279

25134

25142

40. RuckdeschelKRichterKMannelOHeesemannJ

2001

Arginine-143 of Yersinia enterocolitica YopP

crucially determines isotype-related NF-kappaB suppression and apoptosis

induction in macrophages.

Infect Immun

69

7652

7662

41. ZaubermanACohenSMamroudEFlashnerYTidharA

2006

Interaction of Yersinia pestis with macrophages:

limitations in YopJ-dependent apoptosis.

Infect Immun

74

3239

3250

42. SodeindeOASampleAKBrubakerRRGoguenJD

1988

Plasminogen activator/coagulase gene in Yersinia

pestis is responsible for degredation of plasmid-encoded outer

membrane proteins.

Infect Immun

56

2749

2752

43. GarciaJTFerracciFJacksonMWJosephSSPattisI

2006

Measurement of effector protein injection by type III and type IV

secretion systems by using a 13-residue phosphorylatable glycogen synthase

kinase tag.

Infect Immun

74

5645

5657

44. HaaseRKirschningCJSingASchrottnerPFukaseK

2003

A dominant role of Toll-like receptor 4 in the signaling of

apoptosis in bacteria-faced macrophages.

J Immunol

171

4294

4303

45. HaoYHWangYBurdetteDMukherjeeSKeitanyG

2008

Structural requirements for Yersinia YopJ inhibition of MAP

kinase pathways.

PLoS One

3

e1375

46. CaseCLShinSRoyCR

2009

Asc and Ipaf Inflammasomes direct distinct pathways for caspase-1

activation in response to Legionella pneumophila.

Infect Immun

77

1981

1991

47. SuzukiTFranchiLTomaCAshidaHOgawaM

2007

Differential regulation of caspase-1 activation, pyroptosis, and

autophagy via Ipaf and ASC in Shigella-infected macrophages.

PLoS Pathog

3

e111

48. TingJPWillinghamSBBergstralhDT

2008

NLRs at the intersection of cell death and

immunity.

Nat Rev Immunol

8

372

379

49. KahlenbergJMLundbergKCKertesySBQuYDubyakGR

2005

Potentiation of caspase-1 activation by the P2X7 receptor is

dependent on TLR signals and requires NF-kappaB-driven protein

synthesis.

J Immunol

175

7611

7622

50. ZhangYMurthaJRobertsMASiegelRMBliskaJB

2008

Type III secretion decreases bacterial and host survival

following phagocytosis of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis by

macrophages.

Infect Immun

76

4299

4310

51. FranchiLKannegantiTDDubyakGRNunezG

2007

Differential requirement of P2X7 receptor and intracellular

K+ for caspase-1 activation induced by intracellular and extracellular

bacteria.

J Biol Chem

282

18810

18818

52. ClausenBEBurkhardtCReithWRenkawitzRForsterI

1999

Conditional gene targeting in macrophages and granulocytes using

LysMcre mice.

Transgenic Res

8

265

277

53. PenzoMMolteniRSudaTSamaniegoSRaucciA

2010

Inhibitor of NF-kappa B kinases alpha and beta are both essential

for high mobility group box 1-mediated chemotaxis

[corrected].

J Immunol

184

4497

4509

54. Lara-TejeroMSutterwalaFSOguraYGrantEPBertinJ

2006

Role of the caspase-1 inflammasome in Salmonella typhimurium

pathogenesis.

J Exp Med

203

1407

1412

55. YamamotoMSatoSHemmiHHoshinoKKaishoT

2003

Role of adaptor TRIF in the MyD88-independent toll-like receptor

signaling pathway.

Science

301

640

643

56. CeladaAGrayPWRinderknechtESchreiberRD

1984

Evidence for a gamma-interferon receptor that regulates

macrophage tumoricidal activity.

J Exp Med

160

55

74

57. PujolCBliskaJB

2003

The ability to replicate in macrophages is conserved between

Yersinia pestis and Yersinia pseudotuberculosis.

Infect Immun

71

5892

5899

58. PalmerLEPancettiARGreenbergSBliskaJB

1999

YopJ of Yersinia spp. is sufficient to cause downregulation of

multiple mitogen-activated protein kinases in eukaryotic

cells.

Infect Immun

67

708

716

59. TaoHLiuWSimmonsBNHarrisHKCoxTC

2010

Purifying natively folded proteins from inclusion bodies using

sarkosyl, Triton X-100, and CHAPS.

Biotechniques

48

61

64

Štítky

Hygiena a epidemiológia Infekčné lekárstvo Laboratórium

Článek Innate Immune Sensing of DNA

Článok vyšiel v časopisePLOS Pathogens

Najčítanejšie tento týždeň

2011 Číslo 4- Parazitičtí červi v terapii Crohnovy choroby a dalších zánětlivých autoimunitních onemocnění

- Očkování proti virové hemoragické horečce Ebola experimentální vakcínou rVSVDG-ZEBOV-GP

- Koronavirus hýbe světem: Víte jak se chránit a jak postupovat v případě podezření?

-

Všetky články tohto čísla

- Low Diversity Variety Multilocus Sequence Types from Thailand Are Consistent with an Ancestral African Origin

- Genetic Assignment Methods for Gaining Insight into the Management of Infectious Disease by Understanding Pathogen, Vector, and Host Movement

- Innate Immune Sensing of DNA

- Engineered Resistance to Development in Transgenic

- -Mediated Detoxification of Reactive Oxygen Species Is Required for Full Virulence in the Rice Blast Fungus

- SLO-1-Channels of Parasitic Nematodes Reconstitute Locomotor Behaviour and Emodepside Sensitivity in Loss of Function Mutants

- Structure-Function Analysis of the LRIM1/APL1C Complex and its Interaction with Complement C3-Like Protein TEP1

- A Effector with Enhanced Inhibitory Activity on the NF-κB Pathway Activates the NLRP3/ASC/Caspase-1 Inflammasome in Macrophages

- The MARCH Family E3 Ubiquitin Ligase K5 Alters Monocyte Metabolism and Proliferation through Receptor Tyrosine Kinase Modulation

- is an Unstable Pathogen Showing Evidence of Significant Genomic Flux

- The Cell Wall Protein CwpV is Antigenically Variable between Strains, but Exhibits Conserved Aggregation-Promoting Function

- Engineering HIV-Resistant Human CD4+ T Cells with CXCR4-Specific Zinc-Finger Nucleases

- SUMO-Interacting Motifs of Human TRIM5α are Important for Antiviral Activity

- Completion of Hepatitis C Virus Replication Cycle in Heterokaryons Excludes Dominant Restrictions in Human Non-liver and Mouse Liver Cell Lines

- : Reservoir Hosts and Tracking the Emergence in Humans and Macaques

- On Being the Right Size: The Impact of Population Size and Stochastic Effects on the Evolution of Drug Resistance in Hospitals and the Community

- Bacterial and Host Determinants of MAL Activation upon EPEC Infection: The Roles of Tir, ABRA, and FLRT3

- Respiratory Syncytial Virus Interferon Antagonist NS1 Protein Suppresses and Skews the Human T Lymphocyte Response

- NF-κB Hyper-Activation by HTLV-1 Tax Induces Cellular Senescence, but Can Be Alleviated by the Viral Anti-Sense Protein HBZ

- Human Cytomegalovirus IE1 Protein Elicits a Type II Interferon-Like Host Cell Response That Depends on Activated STAT1 but Not Interferon-γ

- A New Model to Produce Infectious Hepatitis C Virus without the Replication Requirement

- PLOS Pathogens

- Archív čísel

- Aktuálne číslo

- Informácie o časopise

Najčítanejšie v tomto čísle- NF-κB Hyper-Activation by HTLV-1 Tax Induces Cellular Senescence, but Can Be Alleviated by the Viral Anti-Sense Protein HBZ

- Bacterial and Host Determinants of MAL Activation upon EPEC Infection: The Roles of Tir, ABRA, and FLRT3

- : Reservoir Hosts and Tracking the Emergence in Humans and Macaques

- On Being the Right Size: The Impact of Population Size and Stochastic Effects on the Evolution of Drug Resistance in Hospitals and the Community

Prihlásenie#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zabudnuté hesloZadajte e-mailovú adresu, s ktorou ste vytvárali účet. Budú Vám na ňu zasielané informácie k nastaveniu nového hesla.

- Časopisy