-

Články

- Časopisy

- Kurzy

- Témy

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Hypoxia and Temperature Regulated Morphogenesis in

Candida albicans is an important cause of human disease that occurs if the fungus proliferates strongly on skin surfaces or in several internal organs causing superficial and systemic mycosis. Remarkably, at low cell numbers, C. albicans is also a normal inhabitant of mucosal surfaces and the gut and it is believed that its transition from the commensal to the virulent, highly proliferative state is a key event that initiates fungal disease. In the gut and other body niches, C. albicans adapts to an oxygen-poor environment, which downregulates its virulence traits including the ability to form hyphae. We report on a set of four transcription factors in C. albicans that form an interdependent regulatory circuit, which downregulates filamentation specifically under hypoxia at slightly lowered body temperatures (≤ 35°C). Disturbance of this circuit is expected to initiate the fungal virulence and proliferation in predisposed patients.

Published in the journal: Hypoxia and Temperature Regulated Morphogenesis in. PLoS Genet 11(8): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1005447

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1005447Summary

Candida albicans is an important cause of human disease that occurs if the fungus proliferates strongly on skin surfaces or in several internal organs causing superficial and systemic mycosis. Remarkably, at low cell numbers, C. albicans is also a normal inhabitant of mucosal surfaces and the gut and it is believed that its transition from the commensal to the virulent, highly proliferative state is a key event that initiates fungal disease. In the gut and other body niches, C. albicans adapts to an oxygen-poor environment, which downregulates its virulence traits including the ability to form hyphae. We report on a set of four transcription factors in C. albicans that form an interdependent regulatory circuit, which downregulates filamentation specifically under hypoxia at slightly lowered body temperatures (≤ 35°C). Disturbance of this circuit is expected to initiate the fungal virulence and proliferation in predisposed patients.

Introduction

Candida albicans is a regular fungal inhabitant of the human gastrointestinal tract and the skin [1–3] but in predisposed patients it can also cause life-threatening systemic disease [4]. Systemic candidiasis occurs if resident fungi translocate to the blood and proliferate massively in extraintestinal organs [5,6]. Currently, the requirements for C. albicans commensalism are being investigated using murine models of colonization, in which fungi are fed orally and monitored during transit and following exit of the gut [7–11]. In all studies, C. albicans cells growing in the gut lumen were found to propogate in the yeast form and not in the alternative hyphal form. Transciptomal analyses revealed that C. albicans adapts to conditions in the mouse gut or in internal organs by upregulation of genes related to growth, stress-resistance and cell surface components [12]. Several proteins required for gut colonization were identified by their defective mutant phenotypes [9,10,12]. In contrast, mutants lacking the transcription factor Efg1 or its homologue Efh1 were found to hyperproliferate in the murine gut [7–9], while overproduction of the Efg1-antagonist Wor1 stimulated excessive proliferation [9]. These results suggested that C. albicans limits its gastrointestinal growth by the repressive transcriptional activity of the Efg1 protein [8]. Gut mucosal damage, deficiencies in immune defenses and defects of the gut probiotic microbiome have been described as essential preconditions to allow translocation and systemic dissemination of C. albicans originating from the gut [11,13]. Despite this knowledge, the environmental cues and signaling pathways favouring commensal growth of C. albicans and its transition to the invasion and dissimination states are largely unclear.

Oxygen-poor locations are frequent in the human host and some niches including the gut may be anoxic [14,15], while other tissues including tissue of exposed skin are hypoxic [16,17]. Hypoxia has also been verified in the mouse gastrointestinal tract [18]. C. albicans adapts to hypoxia by increasing glycolytic and decreasing respiratory metabolism; furthermore, increased expression of genes required for the oxygen-dependent biosynthesis of compounds including ergosterol and unsaturated fatty acids procures maximal use of residual oxygen [19–21]. Under hypoxia, genes required for ergosterol biosynthesis are induced by the transcription factor Upc2 [20,22], while the transcription factors Efg1 and Ace2 both upregulate glycolysis and downregulate oxidative activities [19,23,24]. Efg1 is required for rapid transcriptomal adaptation to hypoxia [25], it controls the regulation of many hypoxic genes and prevents inappropriate hypoxic regulation of normoxic genes [14,19]. Besides their hypoxic metabolic functions, Efg1 and Ace2 also regulate the yeast-to-hypha transition, an important virulence trait of C. albicans, in an oxygen-dependent manner. Under normoxia, efg1 mutants are unable to form hyphae indicating that Efg1 acts as an inducer of morphogenesis [26,27]. In contrast, Efg1 represses hyphal growth under hypoxia, which is apparent by hyperfilamentous growth of efg1 mutants during hypoxic growth on an agar surface [19,23,28] or during embedment in agar [4,29] but not during growth in liquid media. The increased hyperfilamentous phenotype of an efg1 efh1 double mutant demonstrated further that the Efg1 homolog Efh1 acts synergistically with Efg1 [23]. The function of Efg1 as a hypoxic repressor was strikingly temperature-dependent since efg1 mutants were hyperfilamentous at temperatures ≤ 35°C, while at 37°C they were unable to form hyphae under both hypoxia and normoxia [19]. In contrast to Efg1, the Ace2 protein was found to be largely dispensable for hyphal morphogenesis under normoxia [30–32] but it was required for filamentation under hypoxia [30,32]. Thus, Efg1 and Ace2 have opposing functions under hypoxia and recent results suggested that Efg1 represses ACE2 expression [32], as well as expression of Ace2 target genes [32,33] under normoxia.

Both described hypoxic functions of Efg1, i. e. to regulate yeast proliferation of C. albicans in vitro and in the mouse gut in vivo, may be directed by similar if not identical regulatory circuits. In support of this notion, as compared to the wild-type strain, an efg1 mutant not only was hyperproliferative in the mouse gut [7–9] but it also showed increased extraintestinal dissemination in animals exposed to hypoxia [34] and increased virulence in orally-inoculated mice [35]; in contrast, the virulence of the efg1 mutant was strongly reduced in the systemic model of bloodstream-infection, i. e. under increased oxygen levels [27,35]. Hypoxia by decreased blood flow in individual gut villi had previously been shown to favor invasion and translocation of C. albicans across enterocytes [36]. Conceivably, the hypoxic repressor functions of Efg1 are relevant not only at temperatures <37°C, i.e. for fungal colonization of exposed skin tissue but also for translocation across gut epithelia. Here we identify a transcriptional regulatory hub describing the functions of Efg1 under hypoxia that controls the proliferation and morphogenesis of C. albicans in oxygen-limiting environments.

Results

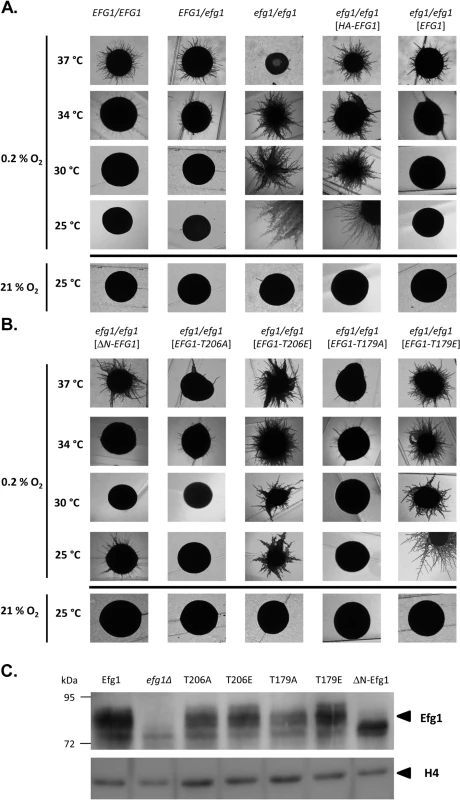

Efg1 hypoxic function requires its unmodified N-terminus

Under hypoxia, Efg1 has been described as a temperature-dependent regulator of morphogenesis because it suppresses filamentation during surface growth at temperatures ≤35°C [19], while at 37°C it is required for hyphal growth [19] as under normoxia [26,27]. Properties of the efg1 mutant were re-confirmed by growth on the surface of YPS agar, which under normoxia does not induce hypha formation in C. albicans [37]. Under hypoxia (0.2% O2), the efg1 mutant was unable to filament at 37°C, while it showed vigorous hyphal outgrowth at 34, 30 and 25°C; in contrast, under normoxia no filamentation was observed at 25°C (Fig 1A). At 37°C under hypoxia, the defective filamentation of an efg1 homozygous mutant on YPS agar was fully restored not only by native Efg1 but also by an N-terminally HA-tagged Efg1 variant (Fig 1A) or by an Efg1 variant carrying a N-terminal deletion (Fig 1B), as under normoxia [38]. In contrast, at 25, 30 or 34°C the synthesis of HA-Efg1 did not prevent hyperfilamentation in an efg1 genetic background, while native unmodified Efg1 had this activity (Fig 1A). The repressing function of authetic Efg1 was slightly reduced by deleting residues 9 to 74 (ΔN-Efg1) since colonies grown at 25°C (but not at 30 or 34°C) showed residual filamentation (Fig 1B). Thus, the morphogenetic repressor function of Efg1 requires its native N-terminus.

Fig. 1. Hypoxia and temperature dependent filamentation regulated by Efg1 variants.

(A, B) Colony phenotypes. Strains were grown under hypoxia (0.2% O2) on the surface of YPS agar at 37°C (3 d), 34°C (3 d), 30°C (3 d) or 25°C (4 d) and under normoxia (21% O2) at 25°C (4 d). (C) Efg1 immunoblot. Strains werμe grown on YPS agar for 60 h at 25°C before cell harvesting by scraping off the colonies. 75 μg of protein in cell extracts were separated by SDS-PAGE (8% acrylamide) and immunoblots were developed using anti-Efg1 antiserum. Levels of histone H4 (loading control) were detected by anti-histone H4 antibodies. Strains tested were CAF2-1 (EFG1/EFG1), BCA0901 (EFG1/efg1), HLC52 (efg1/efg1), HLCEEFG1 (efg1/efg1 [HA-EFG1]), HLCPEFG1 (efg1/efg1 [EFG1]), HLCNEFG1 (efg1/efg1 [ΔN-EFG1]), HLCEEFG1T206A (efg1/efg1 [EFG1-T206A]), HLCEEFG1T206E (efg1/efg1 [EFG1-T206E]), HLCEEFG1T179A (efg1/efg1 [EFG1-T179A]) and HLCEEFG1T179E (efg1/efg1 [EFG1-T79E]). The structural requirements for hypoxic Efg1 functions were explored further by single-site mutated variants mutated for residues T206 and T179. T206 fits the consensus sequence for phosphorylation by PKA [39] and T179 is considered as the phosphorylation site of the Cdc28-Hgc1 kinase complex [33]; phosphorylation of both residues is needed for efficient hypha formation under normoxia [33,39]. EFG1 versions encoding T206A, T206E, T179A and T179E variants were integrated into the genome of an efg1 mutant and filamentation phenotypes of transformants were examined. All Efg1 variants were produced at similar levels during hypoxic growth (Fig 1C) as under normoxia [38], which was assayed by immunoblotting of cell extracts using a newly generated anti-Efg1 antiserum (S1 Fig). Interestingly, at 25, 30 and 34°C, both non-phosphorylatable variants T206A and T179A effectively repressed filamentation, while Efg1 variants mimicking phosphorylation (T206E and T179E) were unable to act as repressors (Fig 1B). This result suggests that opposite to its normoxic functions, the phosphorylated forms of Efg1 are inactive in hypoxic repression, while the non-phosphorylated forms are active.

Collectively, the results suggest that normoxic and hypoxic functions of Efg1 have different structural requirements. An unmodified native N-terminus of Efg1 and the lack of T206/T179 phosphorylation appear essential for its repressive functions under hypoxia at temperatures slightly below 37°C.

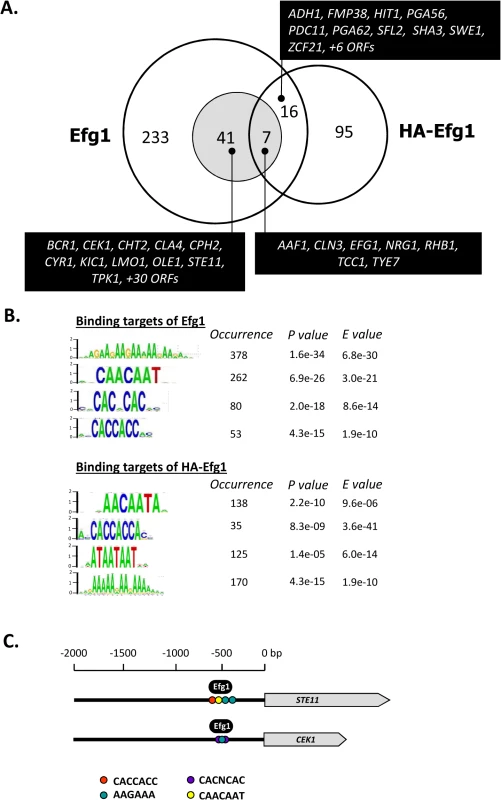

Genomic binding of native and HA-tagged Efg1 under hypoxia

The above experiments had shown that native but not HA-tagged Efg1 is active for morphogenetic repression under hypoxia at 25°C and 30°C. Next, we sought to identify genes that are hypoxically repressed by Efg1 but not HA-Efg1 under hypoxia. For this purpose genomic binding sites for both Efg1 versions were determined by ChIP chip analyses and compared. Binding of native Efg1 was determined in the Efg1+ strain CAF2-1 using anti-Efg1 antibody for immunoprecipitation and the efg1 mutant HLC52 [27] as the background control strain; binding of HA-Efg1 was established using anti-HA antibody and strain CAF2-1 as the reference control [40]. Cells were grown at 30°C (i. e. a temperature compatible with the hypoxic repressor function of Efg1) in liquid glucose-containing YPD medium. This experimental setup was chosen to focus on hypoxia-regulated targets under clearly defined conditions using uniformly exponentially-growing yeast cells and to exclude other targets, e. g. related to differential filamentation. Furthermore, normoxic targets for HA-Efg1 had been previously determined in identical conditions [40] and provided a useful dataset for comparisons.

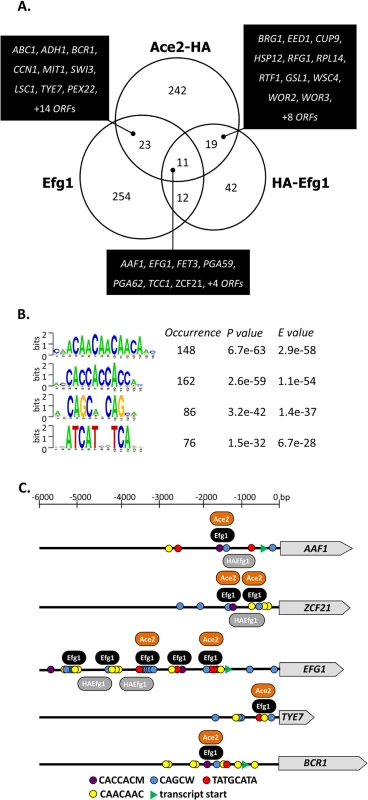

Genomic binding sites for native Efg1 (221 sites corresponding to 300 ORFs) greatly outnumbered those for HA-tagged Efg1 (100 sites corresponding to 118 ORFs) and surprisingly little overlap was found for sites binding both proteins (23 sites); 198 sequences were exclusively bound by native Efg1 under hypoxia (Fig 2A). Little overlap was also detected between targets of HA-Efg1 under hypoxia and normoxia [40] (S2 Fig). Binding sites for both proteins are specified in S1 Table and are available at (http://www.candidagenome.org/download/systematic_results/Desai_2014/). Hypoxic binding occurred exclusively in promoter regions upstream of ORFs, marking these genes as potential regulatory targets (in case of divergently transcribed genes both ORFs were considered as regulatory targets). A significant subset of identified genes has a known or suspected role in hyphal growth of C. albicans (shaded area in Fig 2A). Genes binding both Efg1 and HA-Efg1 included EFG1 itself [40], as well as seven genes encoding general morphogenetic regulators comprising NRG1, TCC1 and TYE7. Forty-one genes were only bound by native Efg1 but not by HA-Efg1 under hypoxia including BCR1, CEK1, CPH2, CYR1, STE11 and TPK1. Consensus sequences in promoters binding Efg1 proteins were calculated using the program RSAT dyad analysis [41] and revealed an enrichment for CA-containing motifs for both Efg1 and HA-Efg1 (Fig 2B) that may represent binding sites. This result suggests that although target promoters differ, untagged and tagged Efg1 proteins bind to identical sequences under hypoxia. Interestingly, the binding sequences resemble CA-containing sequences bound by HA-Efg1 during hyphal induction under normoxia but differ from the major binding site (EGR-box TATGCATA) in normoxically grown, yeast-form cells [40].

Fig. 2. Genomic binding sites for Efg1.

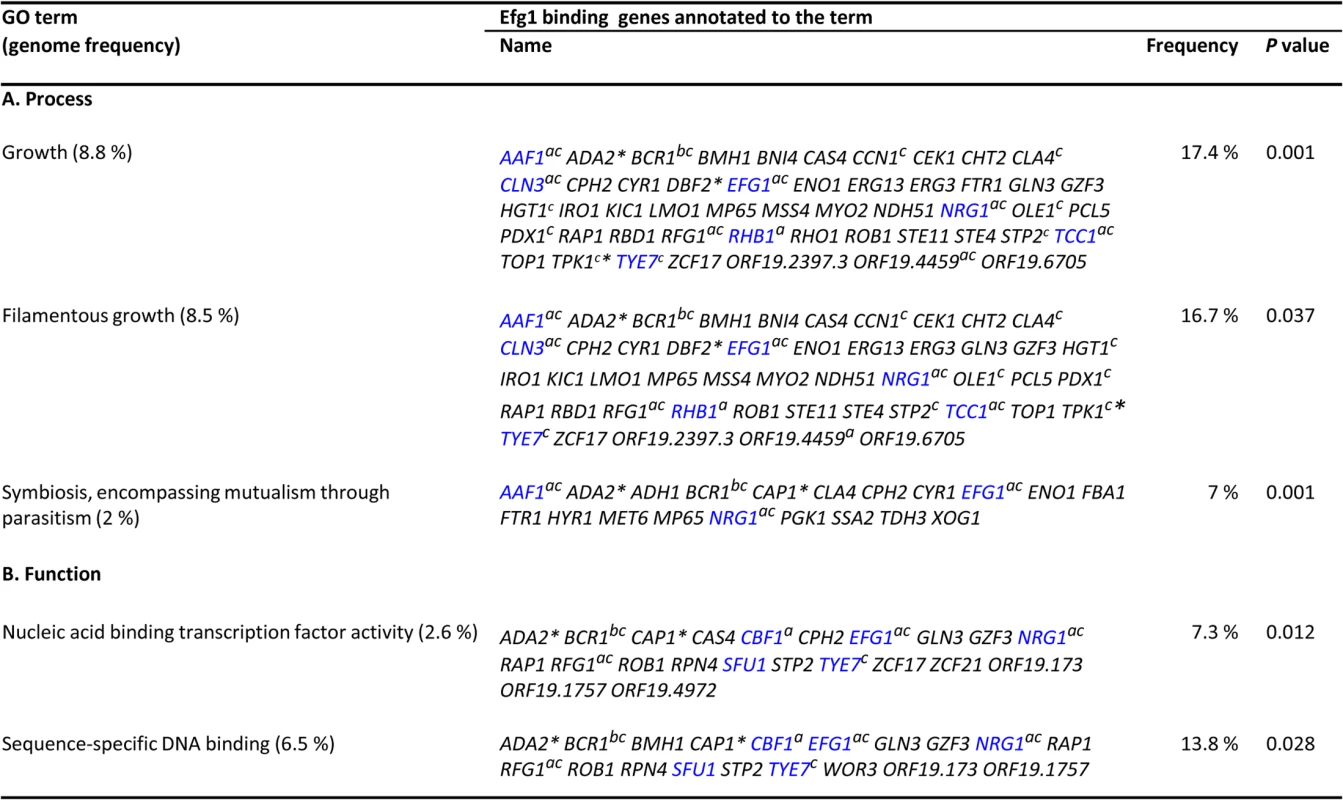

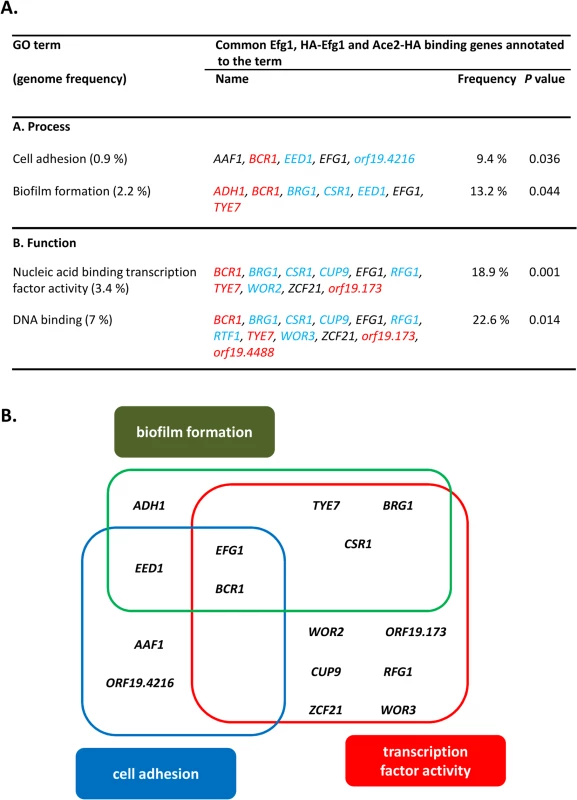

(A) Venn diagram listing numbers of genes bound by untagged Efg1 (Efg1) and HA-Efg1 under hypoxia. For Efg1, genomic binding sites were derived from ChIP chip experiments comparing strains CAF2-1 (EFG1/EFG1) and HLC52 (efg1/efg1); for HA-Efg1, strains HLCEEFG1 (efg1/efg1 [HA-EFG1]) and DSC11 (efg1/efg1 [EFG1]) were compared. The shaded circle encompasses genes in filamentous growth. (B) The program RSAT dyad analysis [43] was used to predict the DNA binding motif of Efg1 and HA-Efg1 from genomic binding regions. Predicted dyads for Efg1 and HA-Efg1 binding sites under hypoxic growth were ranked and the top-ranked sequences are shown with their P-/E-values. (C) Position of Efg1 binding sites in promoter regions. Arrows indicate ORFs of genes STE11, CEK1 and CPH1 and consensus sequences representing potential Efg1 binding sites in promoter regions are indicated by colored circles. The position of identified Efg1 binding (black oval) in STE11 and CEK1 promoters is indicated. Gene ontology (GO) analysis of genes binding native Efg1 under hypoxia revealed an enrichment for genes involved in filamentation and transcription factor activity (Fig 3), as expected from the Venn diagram (Fig 2A). Several of these genes had previously been identified as targets of HA-tagged Efg1 grown under normoxia in liquid [40] or during biofilm formation [42]. Gene ontology assignments for HA-Efg1 are shown in S3 Fig.

Fig. 3. GO categories of genes binding Efg1 under hypoxia.

GO terms for Efg1 binding targets were identified in ChIP chip data using the CGD GO Term Finder tool (http://www.candidagenome.org/cgi-bin/GO/goTermFinder); the analysis was conducted in June 2013. Genome frequencies of genes corresponding to GO terms are expressed as percentages (gene number relative to 6,525 genes in the C. albicans genome; the frequency of genes binding Efg1 that correspond to a specific GO term are expressed relative to the total number of 287 genes binding Efg1). Superscripts of genes indicate known gene functions: a, Efg1 binding under yeast normoxia [40]; b, Efg1 binding in hypha-inducing conditions [40]; c, Efg1 binding in biofilm-inducing conditions [42]; *genes regulated by Efg1 during GI tract colonisation [8]. Blue Lettering indicates common target genes bound by Efg1 and HA-Efg1 under hypoxia. P values for overrepresented categories were calculated using a hyper geometric distribution with multiple hypothesis correction according to the GO Term Finder tool. The P value cutoff used was 0.05. Transcriptional regulation under hypoxia

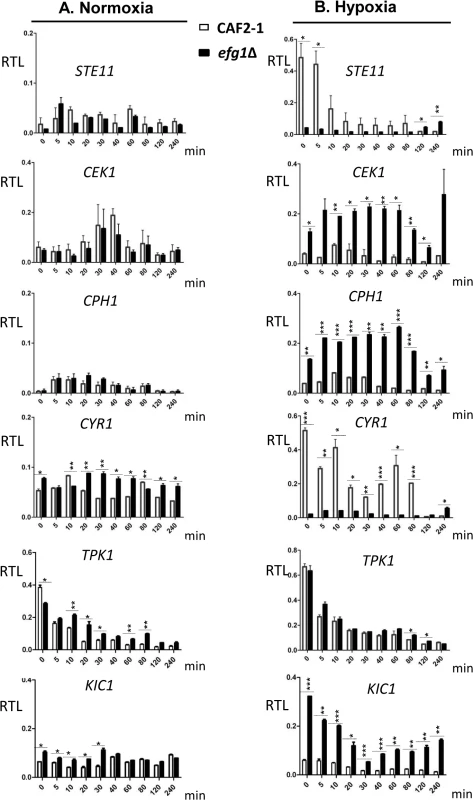

The above results had indicated a subset of genes bound by native but not HA-tagged Efg1, which are known to be involved in the yeast-to-hypha transition. Efg1 binding in promoter regions of these genes suggested that they are transcriptionally regulated by Efg1, explaining the hypoxic repressor function of Efg1 on hyphal morphogenesis. To verify this notion, transcript levels of selected genes were monitored during the shift from normoxia to hypoxia in Efg1+ cells (CAF2-1) and efg1 mutant cells (HLC52). Genes STE11, CEK1 and CPH1 encode members of the Cek1 MAP kinase cascade, which is needed for hypha formation of C. albicans mainly during surface growth [43–45]; Efg1 binding occurs in the promoter region of STE11 and CEK1 genes at the CA-type consensus binding sequences (Fig 2C). Transcripts of genes CYR1 and TPK1 were also analyzed that encode adenylate cyclase and PKA isoform 1, respectively, which are members of the cAMP-dependent pathway of filamentation [46,47]. In addition, the KIC1 transcript encoding a presumed regulator of the Ace2 transcription factor [48] was assayed since Ace2 stimulates hypoxic filamentation [30] (see below).

In the control strain, transcripts for the Cek1 MAP kinase, its downstream transcription factor Cph1 and for the Kic1 protein were present at low levels but increased temporarily at 10–20 min following the hypoxic shift (Fig 4). Remarkably, in efg1 mutant cells, these transcripts were strongly upregulated suggesting hypoxic repression by Efg1. A completely different pattern of regulation was detected for the STE11 gene encoding a kinase upstream of Cek1, as well as for the CYR1 adenylate cyclase gene. Transcript levels for both of these genes decreased strongly during the hypoxic shift in the Efg1+ strain and were significantly downregulated in the efg1 mutant. Thus, the regulation of both STE11 and CYR1 did not fit the pattern of an Efg1-repressed but rather of an Efg1-induced gene; in addition, expression of both genes was down - and not upregulated during the course of hypoxic exposure. The TPK1 transcript also was downregulated under hypoxia but the absence of Efg1 did not affect its levels. Collectively, these results suggest that under hypoxia Efg1 downregulates CEK1, CPH1 and KIC1 transcript levels to suppress filamentation, which becomes evident by the efg1 mutant phenotype (Fig 1). Efg1 binding to STE11, CYR1 and TPK1 promoters may have other functions that are not directly related to repression of hypoxic filamentation.

Fig. 4. Transcriptional regulation of Efg1 target genes under normoxia and hypoxia.

Strains were precultured under normoxia at 30°C in YPD medium and used for inoculation of 200 ml YPD cultures for normoxia, or under 0.2% O2 for hypoxia. Cultures were incubated at 30°C under normoxia or hypoxia, and at the indicated times 20 ml of culture was withdrawn and used for preparation of total RNA. At each time point, two biological replicates and three technical replicates were assayed by qPCR using gene-specific primers. mRNA levels are expressed as means ± SEM of transcript levels relative to the ACT1 transcript (RTL), for normoxia (A) and hypoxia (B) grown cultures. A two-tailed, unpaired t test comparing the RTL values of control strain CAF2-1 and efg1 mutant HLC52 was used to determine the statistical relevance. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. Efg1 represses Cek1-dependent filamentation under hypoxia

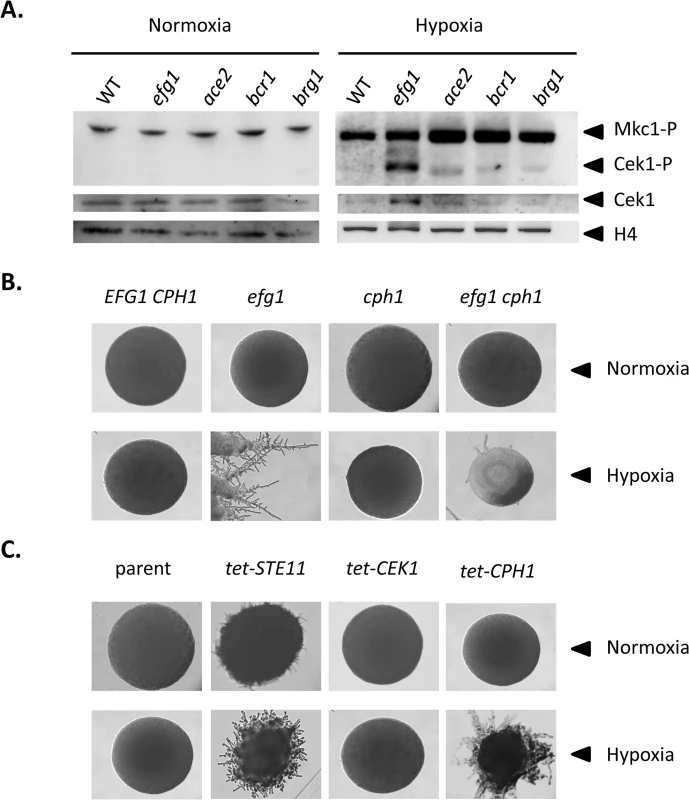

To verify the transcriptional data we analyzed levels of the Cek1 MAPK protein and of its phosphorylated form by immunoblotting in wild-type and mutant strains grown under hypoxia and normoxia. Under hypoxia, the total amount of Cek1 and of its phosphorylated form (Cek1-P) was strongly increased in the efg1 mutant as compared to the wild-type strain, while under normoxia Cek1 levels were unaltered in the mutant and Cek1-P was not detected (Fig 5A). This result matches the observed increase in the CEK1 transcript level in the efg1 mutant (Fig 4B). Activation of MAP kinase activity was specific for Cek1 since the Mkc1 phosphorylation status was unaffected by the presence of Efg1 (Fig 5A).

Fig. 5. Hypoxic filamentation is activated by the Cek1 pathway.

(A) Levels of MAP kinases in C. albicans mutants. C. albicans strains CAF2-1 (WT), HLC52 (efg1), MK106 (ace2), CJN702 (bcr1) and TF022 (brg1) were plated on YPS agar plates and incubated for 60 h at 25°C under normoxia or hypoxia (0.2% O2). Colonies were scraped off the agar and cell extracts were used for immunoblotting. Anti-phospho-p44/42 antibody was used to detect the phosphorylated forms of MAP kinases Mkc1p and Cek1p. Total Cek1 (Cek1) and histone H4 levels (loading control) were detected by anti-Cek1 and anti histone H4 antibodies, respectively. (B, C) Phenotypes of C. albicans strains with altered expression of Efg1 target genes. Filamentation phenotypes were monitored following growth on YPS agar at 25°C under normoxia or hypoxia (0.2% O2) for 3 d. (B) Mutant phenoypes. Comparisons of control strain CAF2-1 (EFG1 CPH1) and homozygous mutants HLC52 (efg1), JKC19 (cph1), HLC54 (efg1 cph1). (C) Overexpression phenotypes. Transformants expressing genes STE11, CEK1 and CPH1 under control of a tetracycline inducible promoter were grown on YPS medium containing 3 μg/ml anhydrotetracycline. Strains included CDC2907 (parent control), CECSTE11 (tet-STE11), CECCEK1 (tet-CEK1) and CDCCPH1 (tet-CPH1). To test if during hypoxic surface growth, excessive filamentation by the Cek1-Cph1 pathway is suppressed by the Efg1 protein we examined filamentation phenotypes under hypoxia in strains lacking or overproducing potential regulator proteins. We observed that a cph1 mutant and colonies of an efg1 cph1 double mutant did not form hyphae, unlike the hyperfilamentous efg1 mutant (Fig 5B). In addition, overexpression of STE11 and CPH1 genes encoding members of the Cek1 signaling pathway by an anhydrotetracyclin-inducible promoter stimulated filamentation in the wild-type genetic background (Fig 5C). In this experiment, the failure of overexpressed CEK1 to induce filamentation may reflect low activity of non-phosphorylated Cek1 in the absence of activation by an upstream kinase. Collectively, the results provide strong evidence that Efg1 represses hypha formation of C. albicans under hypoxia by repressing the biosynthesis and activity of the Cek1 MAP kinase pathway.

Intersection of Ace2 and Efg1 regulatory circuits

Ace2 is a transcription factor that under hypoxia, unlike Efg1 at lower temperatures, is required for filamentation [30]. Efg1 represses the transcription of ACE2 and of Ace2-dependent genes and binds to the ACE2 promoter under normoxia [31, 32]. On the other hand, Ace2 and Efg1 have similar functions to stimulate glycolysis and to repress oxidative metabolism [23, 30]. These results suggested that Ace2 and Efg1 regulatory circuits overlap to jointly control filamentation of C. albicans under hypoxia. To verify this notion we compared genomic binding sites of Ace2 and Efg1 in cells grown under hypoxia. Strain CLvW004 (ACE2-HA/ace2) was constructed, which synthesizes the Ace2 protein with an added C-terminal triple HA-tag. This strain did not show any of the known ace2 mutant phenotypes for antimycin A resistance, wrinkled colony growth [24,30] and sensitivity to the Pmt1 O-mannosylation inhibitor [49] indicating that the Ace2-HA fusion protein is functional (S4 Fig). For the identification of hypoxic Ace2 genomic binding sites, based on preliminary results, a broad ChIP chip screening strategy was chosen to identify all hypoxic targets including those targets requiring the presence of CO2. For this purpose genomic binding sites for Ace2-HA in strain CLvW004 were determined following growth in 0.2% O2/ 6% CO2 and related to results of strain BWP17 synthesizing unmodified Ace2 for background correction; in parallel, normoxic binding sites were determined. Binding sites for Ace2 are listed in S2 and S3 Tables and deposited at http://www.candidagenome.org/download/systematic_results/Desai_2014/.

296 significant genomic Ace2 binding sites were identified in C. albicans promoter regions, while no binding occurred within ORFs (Fig 6A). The majority of binding sites (>80%) was identical in cells grown under hypoxia or normoxia (S5 Fig). Analysis with the RSAT program dyad analysis [41] revealed potential consensus binding sequences CAACAA, CACCAC, CAGCW and ATCAT for Ace2 (Fig 6B). The sequence CAGCW is similar to the CCAGC motif deduced from transcriptomal analyses of Ace2 [30] and matches the binding sequence of S. cerevisiae Ace2 [50]. Interestingly, the CAACAA and CACCAC motifs had also been observed as potential binding sites for native and tagged Efg1 (Fig 2B) suggesting that these sequences are targeted by both Ace2 and Efg1. Genomic positions for both proteins correspond to binding motifs, mostly to the CACCAC sequence, in a selected group of promoters (Fig 6C).

Fig. 6. Genomic binding sites for Ace2.

(A) Venn diagram showing numbers of genes bound by untagged Efg1 (Efg1), HA-Efg1 and Ace2-HA under hypoxia. For Efg1, genomic binding sites were derived from ChIP chip experiments comparing strains CAF2-1 (EFG1/EFG1) and HLC52 (efg1/efg1), for Ace2-HA, strains CLvW004 (ACE2-HA/ace2) and BWP17 were compared. A set of 34 genes is common for Efg1 and Ace2-HA. (B) The program RSAT dyad-analysis [41] was used to predict the DNA binding motif of Ace2-HA from genomic binding regions. Predicted dyads for Ace2-HA binding sites under hypoxic growth were ranked and the top-ranked sequences are shown with their respective P- and E-values. (C) Position of Efg1 and Ace2-HA binding sites in promoter regions of target genes. Arrows indicate ORFs of genes AAF1, TYE7, ZCF21, EFG1 and BCR1. Consensus sequences representing potential Efg1 and Ace2-HA binding sites in promoter regions are indicated by colored circles. The position of common identified sequences for Efg1 (black oval) and Ace2-HA (orange oval) binding in AAF1, TYE7, ZCF21, EFG1 and BCR1 promoters is indicated. 53 promoters bound both Ace2-HA and Efg1 and/or HA-Efg1 under hypoxia (Fig 7A). Gene ontology analysis of the corresponding genes revealed their preferential function as transcription factors to regulate processes of cell adhesion, biofilm formation and morphogenesis (Fig 7B). The transcription factors Brg1 [51] and Bcr1 [52] are known to regulate morphogenesis under normoxia but they also appear to function under hypoxia because they are under joint control of both Ace2 and (HA-) Efg1 in this environment (Fig 7B). Other common hypoxic Ace2/Efg1 target genes encode regulators with more specific functions including Aaf1 [53], Adh1 [54], Eed1 [55], Tye7 [56], Rfg1 [57], Wor2 [58], Wor3 [59] and Zcf21 [60]. In control experiments, binding targets were verified by qPCR following ChIP demonstrating strong enrichment of binding sites for Efg1, HA-Efg1 or Ace2-HA in a selected group of target promoters (S6 Fig). By this sensitive method, binding of HA-Efg1 (in addition to Efg1) was also detected at the BCR1 promoter; furthermore, these data demonstrated the specificity of antibodies used for immunoprecipitation since anti-Efg1 antibody precipitated both Efg1 and HA-Efg1, while anti-HA antibody was specific for HA-Efg1 and Ace2-HA (S6 Fig).

Fig. 7. GO categories of common untagged Efg1 (Efg1), HA-Efg1 and Ace2-HA target genes under hypoxia.

(A) GO terms for target genes identified by ChIP-chip analysis that are common for untagged Efg1, HA-Efg1 and Ace2-HA under hypoxia using the CGD GO Term Finder tool (http://www.candidagenome.org/cgi-bin/GO/goTermFinder); the analysis was conducted in May 2014. Genome frequencies of genes corresponding to GO terms are expressed as percentages (gene number relative to 6,525 genes in the C. albicans genome; the frequency of genes that correspond to a specific GO term are expressed relative to the total number of 53 genes with either a binding region of untagged Efg1 or HA-Efg1 and Ace2-HA present in their 5’-UTR). P values for overrepresented categories were calculated using a hyper geometric distribution with multiple hypothesis correction according to the GO Term Finder tool. The P value cutoff used was 0.05. Colors indicate genes binding only untagged Efg1 (red), only HA-tagged Efg1 (blue) or both Efg1 versions (black). (B) Scheme depicting overlap between GO categories for common Efg1 and Ace2 target genes. In addition, 242 genes were identified that only bound Ace2-HA but not (HA-)Efg1. This group was enriched for genes involved in glycolysis and oxidative metabolism (e. g. PFK2, ACO1, LSC1) confirming previous transcriptomal analyses [30]. Interestingly, genes involved in mitochondrial translation (NAM2, ORF19.4929, ORF19.4705, EAF7, PIM1) were also identified among Ace2 targets. The promoter of the SCH9 gene encoding a kinase repressing hypha formation under hypoxia if CO2 is present [37], was also identified as a hypoxic binding target of Ace2. Collectively, the group of “Ace2-only” genes appears to regulate metabolism and growth but also contains some genes for some relevant morphogenetic regulators including FLO8 [61,62], CAS5 [63], SFL1 [64,65] and WOR1 [58]. Conceivably, under hypoxia activation of FLO8, which is known to be required for CO2 sensing [62], may be mediated by Ace2 (see below).

Efg1-Ace2 and its targets form an interdependent regulatory hub under hypoxia

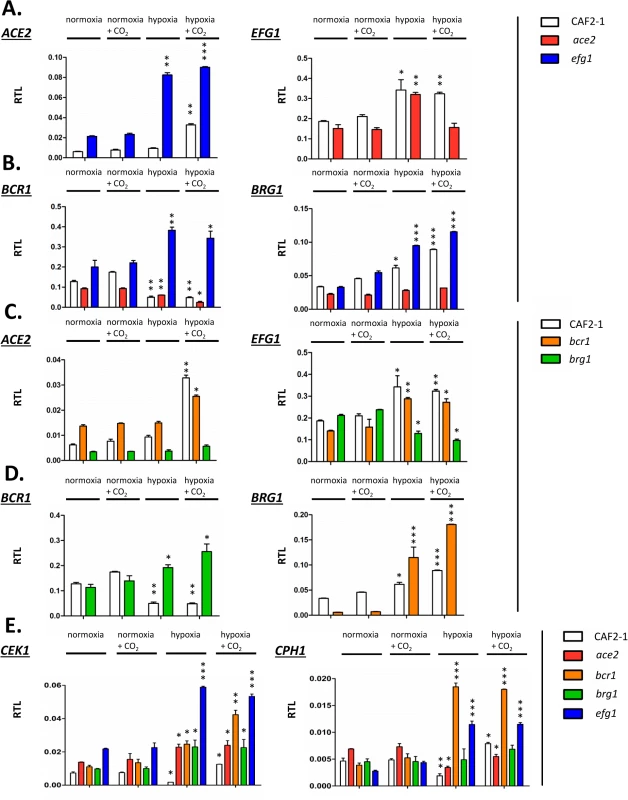

Joint binding of Efg1 and Ace2 to target promoters under hypoxia suggested that both proteins regulate the respective genes on the transcriptional level. To clarify a specific role of hypoxia on gene regulation the transcript levels of selected Ace2-Efg1 target genes were determined under hypoxia and normoxia. Wild-type cells, as well as ace2 and efg1 mutant cells, were grown under normoxia and hypoxia (0.2% O2) both in the absence or presence of CO2 (6% CO2); hypoxia in combination with elevated CO2 levels was tested because previous results had suggested that this environment triggers specific patterns of gene expression [37]. Transcript levels were determined for Ace2-Efg1 target genes under hypoxia and normoxia (Fig 8).

Fig. 8. Transcriptional regulation of Efg1 and Ace2 target genes under hypoxia.

Strains CAF2-1 (control), the ace2 mutant MK106 and the efg1 mutant HLC52 were precultured under normoxia at 30°C in YPD medium and used for inoculation of 100 ml YPD cultures. Cultures were incubated at 30°C under normoxia, under normoxia with addition of CO2 (6%), under hypoxia (0.2% O2) or under hypoxia with addition of CO2 (0.2% O2, 6% CO2) until OD600 = 0.5 and total RNA was then isolated. Relative transcript levels were determined using ACT1 transcript as the reference, as described in Fig 4. (A) Relative transcript levels (RTL) for the ACE2 transcript in strains CAF2-1 and HLC52 (efg1) and for the EFG1 transcript in strains CAF2-1 and MK106 (ace2). (B to D) Relative transcript levels for the indicated transcripts in strains CAF2-1 (control), HLC52 (efg1), MK106 (ace2), CJN702 (bcr1) and strain TF022 (brg1). (E) Relative levels of CEK1 and CPH1 transcripts. Error bars represent standard deviation of the means. A two-tailed, unpaired t test comparing the cycle threshold values of samples grown in hypoxic and normoxic conditions for each mutant was used to determine the statistical relevance: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. First, mutual regulation of EFG1 and ACE2 was examined. In the wild-type strain, the ACE2 transcript was strongly upregulated under hypoxia but only in the presence of CO2; upregulation did not require CO2 in the efg1 mutant (Fig 8A) suggesting that Efg1 strongly represses ACE2 under hypoxia also in the absence of CO2. The EFG1 transcript level was upregulated about twofold under hypoxia in the wild-type strain; this occurred even in the ace2 mutant in the absence but not in the presence of CO2. This mutual regulatory pattern of both genes indicated that under hypoxia, Efg1 acts as a transcriptional repressor independently of CO2, while Ace2 requires CO2 for its induction activity.

In a similar manner we analysed the hypoxic expression of two Ace2-Efg1 target genes encoding key morphogenetic regulators during biofilm formation under normoxia (BCR1, BRG1) (Fig 8B). Bcr1 is a positive regulator of biofilm formation, cell surface composition and filamentation [52,66,67], while Brg1 (Gat2) promotes hypha-specific gene expression during hyphal elongation [51,68,69] and promotes ACE2 expression under normoxia [32]. The BCR1 transcript was downregulated in the wild-type strain but upregulated in the efg1 mutant under normoxia but more strongly under hypoxia revealing Efg1 as a strong hypoxic repressor of BCR1. In the ace2 mutant the BCR1 transcript was downregulated more strongly in the presence than in the absence of CO2 suggesting that Ace2 upregulates BCR1 in this environment, counteracting Efg1-mediated repression. In contrast to BCR1 regulation, BRG1 expression was upregulated in the wild-type strain under hypoxia and this upregulation was even enhanced in an efg1 mutant but reduced in the ace2 mutant. Thus, although BCR1 and BRG1 genes are regulated differently under hypoxia, Efg1 and Ace2 regulate these genes similarly, with Efg1 acting as repressor and Ace2 as an inducer of gene expression. Other genes encoding relevant transcription factors, including Tye7 [56], Aaf1 [53] and Zcf21 [60,70], were also controlled by Efg1/Ace2 (S7 Fig); these proteins regulate glycolysis, biofilm formation and/or commensalism of C. albicans.

In a previous report Bcr1 and Brg1 had been shown to bind to the EFG1 promoter [42] suggesting feedback regulation between EFG1-ACE2 and BCR1/BRG1 genes under normoxia. To clarify the regulation under hypoxia ACE2 and EFG1 transcript levels were determined in bcr1 or brg1 mutants. The ACE2 transcript was strongly downregulated in the brg1 mutant in all conditions and largely increased in the bcr1 mutant (not further increasing the already elevated level under hypoxia/CO2) (Fig 8C). Thus, Brg1 activates and Bcr1 represses ACE2 transcript levels. Brg1 also functions as an activator of the EFG1 transcript under hypoxia, which did not increase in the brg1 mutant in this condition.

On the other hand, gene products of BCR1 and BRG1 also mutually acted as negative regulators since the hypoxic downregulation of the BCR1 transcript did not occur in a brg1 mutant (showing even transcript upregulation) and the BRG1 transcript was upregulated in the bcr1 mutant under hypoxia (Fig 8D). Under normoxia, however, the BRG1 transcript was strongly reduced in the bcr1 mutant indicating that Bcr1 is a normoxic inducer but a hypoxic repressor for BRG1. Collectively, the results indicate that EFG1, ACE2, BCR1 and EFG1 genes form an interconnected regulatory hub, in which each participant regulates expression of the co-regulators. The transcriptional output of this unit is specific for hypoxia and is influenced significantly by CO2 levels.

The Efg1-Ace2 regulatory hub regulates hyphal morphogenesis via the Cek1 pathway under hypoxia

The above transcript analyses had revealed that both CEK1 and CPH1 genes are repressed by Efg1 under hypoxia (Fig 4). Because Efg1 is part of an interconnected regulatory hub we re-examined the hypoxic/normoxic ratios of both transcripts in the respective mutant backgrounds (Fig 8E). In the wild-type strain, CEK1 and CPH1 transcripts were lowered in a hypoxic atmosphere without CO2 but reached normoxic levels in the presence of CO2 (Fig 8E). The repressive effect of Efg1 on both genes in this environment was clearly evident by strongly increased transcript levels in the efg1 mutant. Under normoxia the Efg1 co-regulators Ace2, Bcr1 and Brg1 did not greatly influence CEK1 or CPH1 transcript levels. However, under hypoxia these regulators all repressed the CEK1 transcript, while the CPH1 transcript was downregulated only by Bcr1 (and Efg1). Consistently, protein levels of Cek1 and its phosphorylated form Cek1-P was upregulated under hypoxia (Fig 5A). Collectively, these results confirm the conclusion that Efg1 and its co-regulators control the Cek1 MAP kinase pathway.

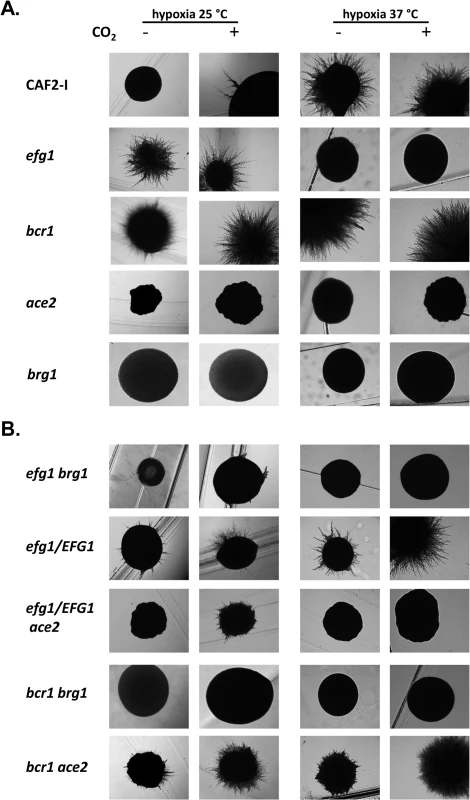

To examine if and how members of the Efg1-Ace2 regulatory hub influence hyphal morphogenesis the colony phenotypes of control and mutant strains were recorded. Cells were grown on YPS agar under hypoxia or normoxia, in the absence or presence of 6% CO2 and at 25°C or 37°C. Under hypoxia, the control strain CAF2-1 showed no or sparse filamentation at 25°C but strong hypha formation at 37°C (Fig 9A). The efg1 mutant was hyperfilamentous at 25°C but non-filamentous at 37°C verifying the previously reported dual repressor/activator role of Efg1 [19,23,29]. Strong hypha formation was also observed for the bcr1 mutant at 25°C but unlike the efg1 mutant, this mutant had a hyperfilamentous phenotype at 37°C. Both ace2 and brg1 mutant were defective in filamentation; this defect occurred for the ace2 mutant in all conditions, whereas the brg1 mutant was able to filament at 37°C in the presence of CO2. Interestingly, under normoxia the wild-type strain presented vigorous filamentation at 37°C, while all single mutants showed complete or partial (ace2 mutant) filamentation defects (S8 Fig). Thus, the Efg1, Ace2, Bcr1 and Brg1 regulators determine morphogenesis under both hypoxia and normoxia.

Fig. 9. Hypoxic phenotypes of mutants lacking hypoxic regulators.

The strains were grown under hypoxia (0.2% O2) or hypoxia with 6% CO2 on YPS agar for 4 d at 25°C or at 37°C for 3 d. (A) Strains included CAF2-1 (control), homozygous single mutants HLC52 (efg1), CJN702 (bcr1), MK106 (ace2) and TF022 (brg1). (B) Double knockout strains PDEB4 (efg1 brg1), PDBB4 (bcr1 brg1) and CLvW024 (bcr1 ace2) were tested. ACE2 could not be disrupted in an efg1 mutant background; therefore, the heterozygous mutant strain CLvW047 (efg1/EFG1, ace2/ace2) was constructed and its phenotype was compared to the efg1/EFG1 strain DSC11. To establish if the hyperfilamentous phenotype of the efg1 and bcr1 mutants at 25°C requires Ace2 and/or Brg1 proteins double mutants were constructed and tested (Fig 9B). The construction of a homozygous efg1 ace2 double mutant failed repeatedly suggesting that a C. albicans strain lacking both Efg1 and Ace2 is not viable; therefore, an ace2/ace2 efg1/EFG1 heterozygous mutant (CLvW047) was constructed. Filamentation of the efg1/EFG1 heterozygote was slightly but reproducibly increased at 25°C as compared to the control strain, while filamentation was reduced in strain CLvW047. The hyperfilamentous phenotype of the bcr1 mutant (especially in the presence of CO2) was also reduced in the bcr1 ace2 double mutant. These results suggest that the increased hypha formation of efg1 and bcr1 mutants requires Ace2. The Brg1 protein is also needed for this phenotype because efg1 brg1 and bcr1 brg1 double mutants were completely defective for filamentation at 25°C; at 37°C, Brg1 was also needed for the bcr1 phenotype in the absence of CO2. In summary, the results indicate that hyphal morphogenesis of C. albicans under hypoxia is effectively repressed by Efg1 and Bcr1, counteracting the stimulatory effects of the Ace2 and Brg1 proteins.

Discussion

C. albicans is an opportunistic pathogen that inhabits the human host as a harmless commensal but that also can turn into a serious pathogen, which causes tenacious superficial and deadly systemic fungal disease. Candidiasis is typically caused by the strong proliferation of the same C. albicans strain that had inhabited the patient as a commensal before [6] raising questions about the molecular events that occur in the pathogen during the commensal-to-pathogen transition. As a commensal, C. albicans colonizes the gut and partly also mucosal surfaces [2,71–73]. Recent results have suggested that the fungus actively restrains its proliferation in the gut by transcriptional regulators Efg1 and Efh1 [7,8,74], while the Wor1 protein enhances gut colonization [9]. Events in the gut occur in oxygen-poor conditions (partly under anoxia) and mostly at elevated carbon dioxide concentrations [14,15]. Here we describe a transcriptional hub that downregulates filamentous growth of C. albicans and favors proliferation of its yeast form under hypoxic conditions. Surprisingly, this repressive activity involves regulators including Efg1, which positively regulate filamentation under normoxia.

Efg1 directs several aspects of morphogenesis and metabolism in C. albicans. It has an important transcriptional role under hypoxia since it contributes to but also prevents hypoxic regulation of many genes [14,19]. The change to a hypoxia-specific pattern of gene expression requires Efg1 at an early time-point following a shift to hypoxia [25]. It is known that Efg1 has a dual role on hyphal morphogenesis: under hypoxia it acts as a hyphal repressor during growth on agar at temperatures ≤ 35°C [19,23,28], while under normoxia, Efg1 is a strong inducer of hypha formation [26,27]. The Efg1 signaling pathway under normoxia comprises adenylate cyclase Cyr1 activity that increases cAMP levels [46,47], which activates PKA isoforms Tpk1/Tpk2 and in turn Efg1 by phosphorylation of residue T206 [39]; an additional phosphorylation of T179 by the Cdc28-Hgc1 complex was also described to occur during hyphal morphogenesis [33]. Here we report that the hypoxic repressor function of Efg1 has specific structural requirements. Efg1 lost its repressor activity, when its N-terminal end was modified by extension and partially by deletion, while under normoxia such variants were active in hyphal induction [38]. Interestingly, chlamydospore formation, which is induced by oxygen limitation, also was found to require an undeleted N-terminus of Efg1 [28]. In addition, phosphomimetic residues at Efg1 phosphorylation sites (T179E, T206E) blocked the hypoxic repressor activity, while the corresponding alanine replacement variants were fully active in repression but inactive for the normoxic induction of hyphae [33,39]. This result corresponds to the lowered CYR1 and TPK1 transcript levels under hypoxia, which predicts lowered PKA activity and reduced T206 phosphorylation, thus resulting in enhanced hypoxic repressor activity of Efg1. With regard to Efg1 target sequences, the deduced CA-rich hypoxic binding sites did not match the major normoxic binding site TATGCATA for the yeast growth form, although Efg1 binds to CA - sequences shortly after hyphal induction [40]. Thus, the different functions of Efg1 as a hypoxic repressor involve different recognition and target sequences, as compared to normoxia.

Previously, synergistic and antagonistic functions of Efg1 and Ace2 transcription factors have been described. Both proteins enhance glycolytic and oxidative patterns of gene expression [23,30] and positively influence filamentation under normoxia [26,27,30–32]. In contrast, under hypoxia Efg1 represses hypha formation [19,23,28], while Ace2 acts as an inducer [30,32]. Efg1 represses ACE2 transcript levels, possibly by direct binding of Efg1 to the ACE2 promoter [32]. To further characterize the functional intersection of both regulators we used ChIP chip analyses to compare their genomic binding patterns under hypoxia. A significant overlap of target genes was identified and the deduced Ace2 binding sequences in promoters included sequences resembling the ACCAGC motif for S. cerevisiae Ace2 [50] but also the above discussed CA-sequences representing hypoxic binding sites for Efg1. Interestingly, the group of genes targeted by both (HA-)Efg1 and Ace2 included important regulators of hyphal growth, biofilm formation and cell adhesion. Targets included the EFG1 promoter, which thereby was confirmed not only as an autoregulatory target for Efg1 [40] but also identified as an Ace2 target. Confirming this result, Ace2 was required for upregulation of the EFG1 transcript in a hypoxic CO2-containing atmosphere, while Efg1 repressed the ACE2 transcript as under normoxia [32]. We analyzed the mode of joint target gene regulation by the Efg1/Ace2 proteins by focusing on BCR1 [52,66,67] and BRG1 (GAT2) [51,68,69], which regulate filamentation and were found to get hypoxically down - and, respectively, upregulated. Surprisingly, these genes were not only targets but also regulators of Efg1/Ace2 and they negatively regulated each other, thereby generating an interconnected regulatory loop (Fig 10A). Efg1 acted as hypoxic repressor of BCR1/BRG1 and also of two other target genes (TYE7, ZCF21), while it was an inducer of AAF1 expression (S3 Fig). In general, Ace2 activated hypoxic expression of all of these genes, especially in the presence of CO2. Transcripts of hypoxia-upregulated genes including EFG1, BRG1 and TYE7 and of hypoxia-downregulated genes including BCR1, AAF1 and ZCF21 were all reduced if ace2 mutant cells were grown hypoxically in the presence of CO2. Interestingly, Ace2 bound strongly to the promoter of the FLO8 gene, which encodes a CO2 sensor interacting with Efg1 [38,62] that is required for white-to-opaque switching and for filamentous growth [61]. Thus, the lack of oxygen combined with an increased level of CO2 generates an environment that elicits a specific regulatory response in C. albicans. These results are reminiscent of and confirm previous results for the hypoxia-specific, CO2-dependent functions of Sch9 kinase [37] and the Ume6 regulator [75].

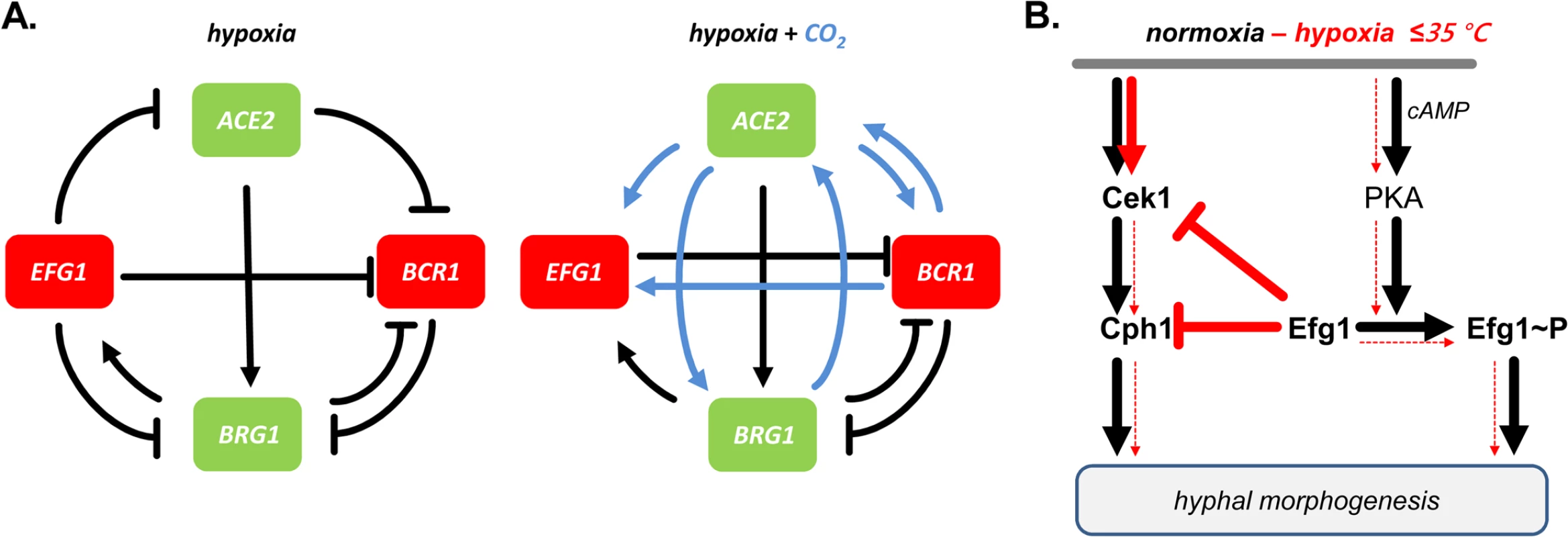

Fig. 10. Models for transcriptional regulation and morphogenesis under hypoxia.

(A) Transcriptional circuits. Hypoxic repressors Efg1 and Bcr1 (red) and hypoxic activators Ace2 and Brg1 (green) are mutually connected in regulatory circuits to regulate hypha formation of C. albicans. Note that regulatory circuits differ depending on the availability of CO2 (blue arrows). (B) Morphogenetic signaling pathways. Under normoxia both Cek1 and PKA kinase pathways trigger hypha formation; Efg1 phosphorylation provides a major signalling input. Under hypoxia, at temperatures ≤ 35°C, low levels of Efg1 phosphorylation block the Cek1 pathway, thereby preventing hyphal induction by both pathways. The morphogenetic output of the described hypoxic regulatory hub was tested by examining hypha formation on agar. The results confirmed that Ace2 is a positive factor for filamentation under hypoxia and partly also under normoxia [30,32], while Efg1 has a dual repressor/activator function under hypoxia/normoxia. Similar to Efg1, Bcr1 acted as a repressor of hypha formation at 25°C, especially in the presence of CO2. Transcript data suggested that in this environment, Ace2 stimulates BCR1 expression to ensure efficient blockage of hypha formation. Brg1 was needed for hypha formation at 37°C under hypoxia, but only in the absence of CO2; in its presence, Brg1 was dispensable for filamentation. The BRG1 transcript was repressed by Efg1 and activated by Ace2, largely independent of CO2. As shown by the phenotypes of double mutants the increased filamentation of efg1 and bcr1 mutants depended on the activity of both Brg1 and Ace2. Thus, under hypoxia C. albicans restrains the stimulatory actions of both Brg1 and Ace2 on hyphal morphogenesis, using Efg1 and Bcr1 as repressors. While this study puts its focus on hypha formation, it is likely that other adaptation processes occurring under hypoxia, especially re-direction of metabolism to a fermentative mode, are regulated by transcription factors that link to the Efg1-Ace2 regulatory hub. Relevant transcription factors for this function could include Tye7 [56], Aaf1 [53] and Zcf21 [60], proteins that regulate glyolysis, biofilm formation and/or commensalism.

Which signaling pathway of morphogenesis is downregulated by Efg1 or Bcr1 proteins? Transcript analyses revealed that the genes encoding MAP kinase Cek1, its downstream target Cph1 and the kinase Kic1 are downregulated specifically under hypoxia by Efg1. The Cek1/Cph1 pathway is known to permit filamentation under normoxia during surface growth of C. albicans [43–45], while in S. cerevisiae, Kic1 is part of the RAM pathway that activates Ace2 activity [48]. The repressive action of Efg1 and its co-regulators on the Cek1 pathway was verified by demonstrating that Efg1, Ace2, Bcr1 and Brg1 all act as repressors of CEK1 transcript levels, while the CPH1 transcript was especially repressed by Bcr1 and Efg1. Furthermore, Efg1 - and Ace2-mediated repression of the Cek1 protein in its non-phosphorylated and phosphorylated form was also demonstrated. Confirming these results, an efg1 cph1 double mutant was unable to filament, while overexpression of CPH1 in a wild-type genetic background triggered hypha formation under hypoxia. These results clearly indicate that C. albicans actively suppresses filamentation mediated by the Cek1 pathway in certain oxygen-poor conditions to promote proliferation of the yeast form (Fig 10B). We have discovered this suppression in vitro slightly below the core body temperature (i. e. < 37°C) but this activity may also occur in the special molecular environment of the gastrointestinal tract or in hypoxic skin tissue [16,17]. Nevertheless, this scenario does not exclude that upregulation of hypoxic filamentation may occur under hypoxia, e. g. if the repressive action of Efg1 is blocked by the Czf1 protein [4]. In this situation, other regulators including Mss11 and Rac1, which were identified by their embedded growth phenotypes [76,77], may also promote hypoxic filamentation. A similar hyperfilamentous phenotype was also reported for mutants lacking the kinase Sch9, although elevated CO2-levels were required in this case [37]. In the human gut, locally increased filamentation could favor anchoring of C. albicans to the epithelium and trigger strong fungal proliferation and systemic invasion mediated by invasion-specific regulators including Eed1 [8,55]. These events may initiate the pathogenic stage of fungal colonization, which will ultimately become apparent by the symptoms of disease. It appears that as a commensal C. albicans attempts to avoid immune responses and to maintain its residency by downregulation of filamentation and possibly other virulence traits. Strengthening of fungal commensalism, e. g. by novel therapeutic molecules or by probiotic microbes could become a promising strategy to combat serious fungal disease.

Materials and Methods

Strains and media

C. albicans strains are listed in S4 Table. Strains were grown in liquid YP medium (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone) containing 2% glucose (YPD) or 2% sucrose (YPS); solid media contained 2% agar. An Invivo200 hypoxia chamber (Ruskinn) was used for hypoxic growth under 0.2% O2 [37]; liquid media were pre-equilibrated overnight under hypoxia before inoculation. Strains overexpressing genes using tetracyclin-inducible promoters were grown in/on YPS medium containing 3 μg/ml anhydrotetracycline.

C. albicans strains expressing EFG1 variants

Oligonucleotides are listed in S5 Table. Plasmid pTD38-HA contains promoter and coding region for an N-terminally hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged Efg1 [38]. In this plasmid, HA-encoding sequences reside on a BglII and BamHI fragment, which were removed in plasmid pPRDEFG1, in which the native EFG1 ORF is preceded by a BamHI site. Other plasmids carrying EFG1 genes encoding Efg1 variants without HA tag were constructed in two steps, as in the case of pPRDNEFG1, in which nucleotides 25 and 222 of the EFG1 ORF are deleted encoding a variant lacking residues Y9 to G74 of Efg1. Primers EFG1BamHIFor and EFG1BamHIRev were used for PCR amplification of the ORF of this variant, using plasmid pBI-HAHYD-D1 [38] as the template. The BamHI-digested PCR fragment was inserted downstream of the EFG1 promoter by ligation with the large BglII fragment of pTD38-HA to generate plasmid p2621NΔEFG1. The PacI-SpeI fragment of this plasmid carrying the junction of the EFG1 promoter and its ORF was then used to replace the corresponding fragment in pTD38-HA. By this procedure, the mutated EFG1 ORF was joined to its 3´-UTR. Similarly, the mutated EFG1 alleles encoding the T206A and T206E mutations were transferred from plasmids pDB1 and pDB2 [39] into pTD38-HA to generate plasmids pPDEFG1T206A and pPDEFG1T206E. Analogous plasmids encoding T179A and T179E Efg1 variants were constructed by mutating the EFG1 ORF by primer pairs EFG1179AFor/Rev and T179Efor/rev, respectively, using site-directed mutagenesis (QuikChange kit, Stratagene). The resultant plasmids pPDEFG1T179E and pPDEFG1T179A encode T179A and T79E variants of Efg1, respectively. All constructs were sequenced using primers EFG1seqFor, EFG1seqRev and Efg1SeqM to confirm the presence of the mutations within EFG1.

Plasmids were integrated into the chromosomal EFG1 locus of efg1 mutant HLC67 by transformation following digestion with PacI in the EFG1 promoter [38]. Their correct chromosomal integration was verified by PCR of gDNA using primers UTREfg1For and Efg1seqM.

C. albicans strains expressing HA-tagged Ace2

For localization studies of Ace2 a heterozygous mutant strain was constructed first. One ACE2 ORF was replaced with a lacZ-ACT1p-SAT1 cassette. The cassette was amplified from plasmid pStLacZ-SAT. All PCR products were separated on an agarose gel and purified using the QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen) before transformation. The oligonucleotides (lacZACE2for/lacZACE2rev) used for amplification, tagged the cassette with 90 bp of flanking sequence complementary to the ACE2 ORF. The strain BWP17 was transformed and transformants were screened for nourseothricin resistance. Integration of the lacZ-ACT1p-SAT1 cassette and replacement of the ACE2 ORF was verified by Southern blot analysis using a probe for SAT1. The resulting heterozygous strain CLvW001 (ace2-lacZ-ACT1p-SAT1/ACE2) was used for C terminal tagging of Ace2. Oligonucleotides ACE2HAFor and ACE2HARev were used to amplify the triple HA-encoding sequence from plasmid p3HA-URA3 thereby adding homologous sequences of the 3‘ - end of the ACE2 ORF and 5‘-UTR of the ACE2 allele to the amplicon. Strain CLvW001 was transformed for C terminal tagging of the remaining ACE2 allele. Correct chromosomal integration at the ACE2 locus was confirmed by colony-PCR using oligonucleotides ACE2For and HARev and by Southern blot analysis. The resulting strain CLvW004, expressing C-terminal HA-tagged Ace2 at the native locus was used to study chromosomal localization of Ace2-HA.

Construction of ACE2 deletion strains

For the deletion of ACE2 in the bcr1 and efg1 mutant background and in strain CAI4, plasmid pSFS5 was used, containing a modified SAT1 flipper cassette [78]. The ACE2 upstream and downstream regions were amplified with the oligonucleotide pairs CAF1ApaI/CAF2XhoI and CAR1SacII/CAR2SacI, for construction of the inner deletion cassette, and oligonucleotide pairs CAF3ApaI/CAF4XhoI and CAR3SacII/CAR4SacI for construction of the outer deletion cassette; the ace2 mutant strain MK106 described by Kelly et al. [24] was used as the reference strain. gDNA of strain SC5314 was used to generate PCR products, which were digested with the indicated restriction enzymes and cloned on both sites of the SAT1 flipper cassette in pSFS5 [78] resulting in plasmids pCLvW90 (inner cassette) and pCLvW91 (outer cassette). The deletion cassettes in plasmids pCLvW90 and pCLvW91 were released by digestion with SacI and ApaI and used for transformation of strains using first the fragment containing the outer cassette and, after excision of the SAT1 flipper cassette, with the second fragment containing the inner cassette. Integration of the deletion cassette was confirmed by colony PCR using oligonucleotides FLP1, which binds within the FLP1 gene, and ACE2UTR5, which binds upstream of the ACE2 ORF. Transformants containing the ACE2 deletion cassette were grown overnight in liquid YCB-BSA medium (20 g yeast carbon base, 4 g bovine serum albumin and 2 g yeast extract per liter) to induce excision of the cassette by FLP-mediated recombination; corresponding strains were identified by their small colony size on YPD plates containing 25 μg/ml nourseothricin. After excision of the second SAT1 flipper cassette, deletion of both ACE2 alleles was confirmed by Southern blot analysis. With this approach both ACE2 alleles were deleted in the bcr1 mutant strain CJN702 [52] resulting in strain CLvW024 and in CAI4 resulting in strain CLvW008. However, deletion of the second ACE2 allele in the efg1 mutant HLC52 [27] was not successful.

In an additional approach we tried to generate the ace2 efg1 double knockout strain by deleting EFG1 in the ace2 mutant strain CLvW008 with the Ura-blaster disruption technique [79] but again we were not able to obtain a homozygous mutant strain suggesting that the double knockout is lethal. The URA3 deletion cassette used for this approach was released from plasmid pBB503 [80] by digestion with HindIII and KpnI. The fragment was purified and transformed into strain CLvW008 and transformants were selected for uridine prototrophy on SD agar. Integration of the cassette was confirmed by colony-PCR. In the resulting strain CLvW041 one chromosomal copy of EFG1 was replaced by the sequence of URA3 flanked by hisG sequences (efg1::hisG-URA3-hisG/EFG; ace2::FRT/ace2::FRT). Attempts to delete the second EFG1 allele after removal of URA3 [79] were not successful.

Construction of BRG1 deletion strains

For deletion of BRG1 gene in efg1 (HLC52) and bcr1 (CJN702) mutants the upstream region of the BRG1 ORF was amplified by genomic PCR using primers BRG1 5UTRKpnIFor/KpnIRev and cloned into the KpnI site of plasmid pSF5S to generate pSFS5-B5. The BRG1 downstream region was amplified using primers BRG13UTRNot1For/SacIRev and cloned into NotI and SacI sites of pSFS5-B5 to generate pSFS5-B5B3. The KpnI-SacI fragment of this plasmid was used to transform efg1 and bcr1 mutant strains, selecting transformants on YPD agar containing nourseothricin (200 μg/ml). Correct genomic integration was confirmed by colony PCR using oligonucleotides FLP1, which binds within the FLP1 gene, and BRG1UpFor, which binds upstream of the BRG1 promoter region. Verified heterozygous transformants were grown in YCB-BSA medium to evict the disruption cassette and retransformed with the disruption fragment, as described [78]. Deletion of both BRG1 alleles was confirmed by negative colony PCR using primer BRG1UpFor, which binds upstream to the BRG1 ORF and BRG1midrev that is specific for the BRG1 ORF. BRG1 alleles were deleted in efg1 (HLC52) and bcr1 (CJN702) mutant strains resulting in strains PDEB4 (efg1 brg1) and PDBB4 (bcr1 brg1) respectively.

C. albicans strains overproducing signalling components

The plasmids pClp10TETSTE11, pClp10TETCEK1 and pClpTETCPH1 [81] encoding Ste11, Cek1 and Cph1 proteins were linearized with StuI within the RPS1 sequence and transformed into C. albicans CEC2907 [81] selecting for uridine prototrophy; the resultant strains were named CECSTE11, CECCEK1 and CECCPH1. Correct plasmid integration at the RPS1 locus was confirmed by colony PCR using primers ClpUL and ClpUR.

Generation of an anti-Efg1 antiserum

A rabbit polyclonal anti-Efg1 antiserum was generated using His10-tagged Efg1 produced in E. coli. The EFG1 ORF (allele ORF19.8243) residing on a XhoI-BamHI fragment was subcloned into pET19b (Novagen), downstream of the T7 RNA polymerase promoter. The resulting plasmid encoded a His10-Efg1 fusion but contained a single CUG codon (residue 449) that encodes serine in C. albicans but leucine in E. coli. This codon was changed to a UCG serine codon by site-directed mutagenesis using oligonucleotides pET19Serinhin/her, resulting in plasmid pET19-His-Efg1Kodon, which was transformed into E. coli Rosetta 2 (DE3)pLysS (Merck). Transformants were grown and the T7 promoter was induced according to instructions of the manufacturer. Cells were resuspended in buffer (20 mM CAPSO pH 9.5, 1 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 20 mM imidazol, 0.1% Triton X100) and broken using 3 passages through a French press cell (Slaminco Spectronic Instruments). Crude extracts were cleared by centrifugation and applied to HisTrap columns connected to an ÄKTA prime plus fraction collector (GE Healthcare). The His10-Efg1 fusion protein was eluted using CAPSO buffer containing 250 mM imidazol. Purified protein (100 μg) was injected on days 1, 14, 28 and 56 in 2 New Zealand White rabbits (performed by Eurogentec, Belgium). One rabbit generated high anti-Efg1 titers in ELISA tests and in immunoblottings (dilution 1 : 5000).

Immunodetection

YPD precultures were grown under normoxia overnight at 30°C in YPD medium and were used to inoculate 40 ml of YPD medium, which had been preincubated overnight under hypoxia (0.2% O2). Starting with an initial density of OD600 = 0.1 cells were grown at 30°C under hypoxia to an OD600 = 1. Cells were harvested, frozen at -70°C for 1 h and then thawed by addition of 500 ml of CAPSO buffer (20 mM CAPSO pH 9,5, 1 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 20 mM imidazole, 0,1% Triton X-100) containing protease inhibitor (Cocktail Complete, Mini, EDTA-free/Roche). Cells were broken at 4°C by shaking with one volume of glass beads (0.45 mm) in a FastPrep-24 shaker (MP Biomedicals) using 4–6 cycles for 40 s at 6.5 ms-1; between cycles cells were placed on ice for 5 min. Debris was removed by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 5 min and protein in the supernatant was determined using the Bradford assay. 45 μg of the crude cell extract was separated by SDS-PAGE (8% polyacrylamide) and analysed by immunoblotting using anti-Efg1 antiserum (1 : 5,000) or anti-histone H4 (Abcam; 1 : 5,000) to detect histone H4 as loading control. Total Cek1 levels were detected by immunoblotting using anti-Cek1 antiserum [10], while phosphorylated Cek1 was detected using monoclonal rabbit anti-phospho-p44/42 antibody (Cell Signaling Technology). Anti-rabbit-IgG-HRP conjugate (1 : 10,000) was used as secondary antibody in all blottings. Signals generated by the chemiluminescent substrate (SuperSignal West Dura; Pierce) were detected by a LAS-4000 mini imager (Fujifilm) and evaluated by the Multi Gauge Software (Fujifilm).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation on microchips (ChIP chip)

The ChIP chip procedure was performed as described by Lassak et al. [40], except that the strains and antibodies used for immunoprecipitation were different. Two independent cultures were assayed for each combination of strains. Precultures were grown overnight under normoxia at 30°C in YPD medium and were shifted to YPD medium precalibrated under hypoxia (0.2% O2, 30°C). The cells were allowed to grow from OD600 = 0.1 to 1. Two sets of strains were analysed: (1) wild-type strain CAF2-1 as test strain and efg1 mutant HLC52 as control strain were compared to determine the genomic localization of untagged Efg1, using anti-Efg1 antibody for chromatin immunoprecipitation; (2) Strain HLCEEFG1 producing HA-tagged Efg1 as test strain and DSC11 (Efg1 producing) as control strain were compared to determine the genomic localization of HA-Efg1 using anti-HA antibody for chromatin immunoprecipitation. C. albicans genomic tiling microarrays were probed pairwise by immunoprecipitated chromatin as described previously [40]. For localization studies of Ace2, precultures were grown overnight under normoxia at 30°C in YPD medium and were used to inoculate medium preincubated under normoxia or hypoxia (0.2% O2) with addition of 6% CO2. Strain CLvW004, producing HA-tagged Ace2 from its native locus and control strain BWP17 were used to determine the genomic localization of Ace2-HA using anti-HA antibody for immunoprecipitation. Significant binding peaks were defined as probes containing four or more signals above background in a 500 bp sliding window; the degree of significance depended on the FDR value. Results were visualized using the program SignalMap (version 1.9). The most significant binding peaks (FDR ≤ 0.05) for Efg1 (202 peak genomic binding sites), HA-Efg1 (106 peak genomic binding sites) and Ace2-HA (272 peak genomic binding sites), which coincided in both replicates, were analysed by the program RSAT dyad-analysis to predict DNA binding sequence [40].

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. Scanlan PD, Marchesi JR. Micro-eukaryotic diversity of the human distal gut microbiota: qualitative assessment using culture-dependent and-independent analysis of faeces. ISME J. 2008;2 : 1183–1193. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2008.76 18670396

2. Ghannoum MA, Jurevic RJ, Mukherjee PK, Cui F, Sikaroodi M, Naqvi A, et al. Characterization of the oral fungal microbiome (mycobiome) in healthy individuals. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6: e1000713. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000713 20072605

3. Iliev ID, Funari VA, Taylor KD, Nguyen Q, Reyes CN, Strom SP et al. Interactions between commensal fungi and the C-type lectin receptor Dectin-1 influence colitis. Science. 2012;336 : 1314–1317. doi: 10.1126/science.1221789 22674328

4. Brown DH Jr, Giusani AD, Chen X, Kumamoto CAFilamentous growth of Candida albicans in response to physical environmental cues and its regulation by the unique CZF1 gene. Mol Microbiol. 1999;34 : 651–662. 10564506

5. Odds FC, Davidson AD, Jacobsen MD, Tavanti A, Whyte JA, Kibbler CC, et al. Candida albicans strain maintenance, replacement, and microvariation demonstrated by multilocus sequence typing. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44 : 3647–3658. 17021093

6. Miranda LN, van der Heijden IM, Costa SF, Sousa AP, Sienra RA, Gobara S, Santos CR, Lobo RD, Pessoa VP Jr, Levin AS. Candida colonisation as a source for candidaemia. J Hosp Infect. 2009;72 : 9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2009.02.009 19303662

7. White SJ, Rosenbach A, Lephart P, Nguyen D, Benjamin A, Tzipori S, et al. Self-regulation of Candida albicans population size during GI colonization. PLoS Pathog. 2007; 3: e184. 18069889

8. Pierce JV, Dignard D, Whiteway M, Kumamoto CA. Normal adaptation of Candida albicans to the murine gastrointestinal tract requires Efg1p-dependent regulation of metabolic and host defense genes. Eukaryot Cell. 2013;12 : 37–49. doi: 10.1128/EC.00236-12 23125349

9. Pande K, Chen C, Noble SM. Passage through the mammalian gut triggers a phenotypic switch that promotes Candida albicans commensalism. Nat Genet. 2013;45 : 1088–1091. doi: 10.1038/ng.2710 23892606

10. Prieto D, Román E, Correia I, Pla J. The HOG pathway is critical for the colonization of the mouse gastrointestinal tract by Candida albicans. PLoS One. 2014;9: e87128. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087128 24475243

11. Koh AY. Murine models of Candida gastrointestinal colonization and dissemination. Eukaryot Cell. 2013;12 : 1416–1422. doi: 10.1128/EC.00196-13 24036344

12. Rosenbach A, Dignard D, Pierce JV, Whiteway M, Kumamoto CA. Adaptations of Candida albicans for growth in the mammalian intestinal tract. Eukaryot Cell. 2010;9 : 1075–1086. doi: 10.1128/EC.00034-10 20435697

13. Jawhara S, Thuru X, Standaert-Vitse A, Jouault T, Mordon S, Sendid B, Desreumaux P, Poulain D. Colonization of mice by Candida albicans is promoted by chemically induced colitis and augments inflammatory responses through galectin-3. J Infect Dis. 2008;197 : 972–980. doi: 10.1086/528990 18419533

14. Ernst JF, Tielker D. Responses to hypoxia in fungal pathogens. Cell Microbiol. 2008;11 : 183–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01259.x 19016786

15. Grahl N, Cramer RA Jr. Regulation of hypoxia adaptation: an overlooked virulence attribute of pathogenic fungi? Med Mycol. 2010;48 : 1–15. doi: 10.3109/13693780902947342 19462332

16. Peyssonnaux C, Boutin AT, Zinkernagel AS, Datta V, Nizet V, Johnson RS. Critical role of HIF-1alpha in keratinocyte defense against bacterial infection. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128 : 1964–1968. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.27 18323789

17. Evans SM, Schrlau AE, Chalian AA, Zhang P, Koch CJ. Oxygen levels in normal and previously irradiated human skin as assessed by EF5 binding. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126 : 2596–2606. 16810299

18. He G, Shankar RA, Chzhan M, Samouilov A, Kuppusamy P, Zweier JL. Noninvasive measurement of anatomic structure and intraluminal oxygenation in the gastrointestinal tract of living mice with spatial and spectral EPR imaging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96 : 4586–45891. 10200306

19. Setiadi ER, Doedt T, Cottier F, Noffz C, Ernst JF. Transcriptional response of Candida albicans to hypoxia: linkage of oxygen sensing and Efg1p-regulatory networks. J Mol Biol. 2006;361 : 399–411. 16854431

20. Synnott JM, Guida A, Mulhern-Haughey S, Higgins DG, Butler G. Regulation of the hypoxic response in Candida albicans. Eukaryot Cell. 2010;9 : 1734–1746. doi: 10.1128/EC.00159-10 20870877

21. Sellam A, van het Hoog M, Tebbji F, Beaurepaire C, Whiteway M, Nantel A. Modeling the transcriptional regulatory network that controls the early hypoxic response in Candida albicans. Eukaryot Cell. 2014;13 : 675–690. doi: 10.1128/EC.00292-13 24681685

22. Silver PM, Oliver BG, White TC. Role of Candida albicans transcription factor Upc2p in drug resistance and sterol metabolism. Eukaryot Cell. 2004;3 : 1391–1397. 15590814

23. Doedt T, Krishnamurthy S, Bockmühl DP, Tebarth B, Stempel C, Russell CL, et al. APSES proteins regulate morphogenesis and metabolism in Candida albicans. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15 : 3167–3180. 15218092

24. Kelly MT, MacCallum DM, Clancy SD, Odds FC, Brown AJ, Butler G. The Candida albicans CaACE2 gene affects morphogenesis, adherence and virulence. Mol Microbiol. 2004;53 : 969–983. 15255906

25. Stichternoth C, Ernst JF. Hypoxic adaptation by Efg1 regulates biofilm formation by Candida albicans. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009;75 : 3663–3672. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00098-09 19346360

26. Stoldt VR, Sonneborn A, Leuker C, Ernst JF. Efg1, an essential regulator of morphogenesis of the human pathogen Candida albicans, is a member of a conserved class of bHLH proteins regulating morphogenetic processes in fungi. EMBO J. 1997;16 : 1982–1991. 9155024

27. Lo HJ, Köhler JR, DiDomenico B, Loebenberg D, Cacciapuoti A, Fink GR. Nonfilamentous C. albicans mutants are avirulent. Cell. 1997;90 : 939–949. 9298905

28. Sonneborn A, Bockmühl DP, Ernst JF. Chlamydospore formation in Candida albicans requires the Efg1p morphogenetic regulator. Infect Immun. 1999;67 : 5514–5517. 10496941

29. Giusani AD, Vinces M, Kumamoto CA. Invasive filamentous growth of Candida albicans is promoted by Czf1p-dependent relief of Efg1p-mediated repression. Genetics. 2002;160 : 1749–1753. 11973327

30. Mulhern SM, Logue ME, Butler G. Candida albicans transcription factor Ace2 regulates metabolism and is required for filamentation in hypoxic conditions. Eukaryot Cell. 2006;5 : 2001–2013. 16998073

31. Bharucha N, Chabrier-Rosello Y, Xu T, Johnson C, Sobczynski S, Song Q et al. A large-scale complex haploinsufficiency-based genetic interaction screen in Candida albicans: analysis of the RAM network during morphogenesis. PLoS Genet. 2011;7: e1002058. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002058 22103005

32. Saputo S, Kumar A, Krysan DJ. Efg1 directly regulates ACE2 expression to mediate cross-talk between the cAMP/PKA and RAM pathways during Candida albicans morphogenesis. Eukaryot Cell. 2014;13 : 1169–1180. doi: 10.1128/EC.00148-14 25001410

33. Wang A, Raniga PP, Lane S, Lu Y, Liu H. Hyphal chain formation in Candida albicans: Cdc28-Hgc1 phosphorylation of Efg1 represses cell separation genes. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29 : 4406–4416. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01502-08 19528234

34. Kim AS, Garni RM, Henry-Stanley MJ, Bendel CM, Erlandsen SL, Wells CL. Hypoxia and extraintestinal dissemination of Candida albicans yeast forms. Shock. 2003;19 : 257–262. 12630526

35. Bendel CM, Hess DJ, Garni RM, Henry-Stanley M, Wells CL. Comparative virulence of Candida albicans yeast and filamentous forms in orally and intravenously inoculated mice. Crit Care Med. 2003;31 : 501–507. 12576958

36. Gianotti L, Alexander JW, Fukushima R, Childress CP. Translocation of Candida albicans is related to the blood flow of individual intestinal villi. Circ Shock. 1993;40 : 250–257. 8375026

37. Stichternoth C, Fraund A, Setiadi E, Giasson L, Vecchiarelli A, Ernst JF. Sch9 kinase integrates hypoxia and CO2 sensing to suppress hyphal morphogenesis in Candida albicans. Eukaryot Cell. 2011;10 : 502–511. doi: 10.1128/EC.00289-10 21335533

38. Noffz CS, Liedschulte V, Lengeler K, Ernst JF. Functional mapping of the Candida albicans Efg1 regulator. Eukaryot Cell. 2008;7 : 881–893. doi: 10.1128/EC.00033-08 18375615

39. Bockmühl DP, Ernst JF. A potential phosphorylation site for an A-type kinase in the Efg1 regulator protein contributes to hyphal morphogenesis of Candida albicans. Genetics. 2001;157 : 1523–30. 11290709

40. Lassak T, Schneider E, Bussmann M, Kurtz D, Manak JR, Srikantha T, et al. Target specificity of the Candida albicans Efg1 regulator. Mol Microbiol. 2011;82 : 602–618. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07837.x 21923768

41. Van Helden J, Rios AF, Collado-Vides J. Discovering regulatory elements in non-coding sequences by analysis of spaced dyads. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28 : 1808–1818. 10734201

42. Nobile CJ, Fox EP, Nett JE, Sorrells TR, Mitrovich QM, Hernday AD, et al. A recently evolved transcriptional network controls biofilm development in Candida albicans. Cell.2012;148 : 126–138. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.048 22265407

43. Liu H, Köhler J, Fink GR. Suppression of hyphal formation in Candida albicans by mutation of a STE12 homolog. Science. 1994;266 : 1723–1726. Erratum in Science. 1995;267 : 217. 7992058

44. Csank C, Schröppel K, Leberer E, Harcus D, Mohamed O, Meloche S, et al. Roles of the Candida albicans mitogen-activated protein kinase homolog, Cek1p, in hyphal development and systemic candidiasis. Infect Immun. 1998;66 : 2713–2721. 9596738

45. Ernst JF. Transcription factors in Candida albicans—environmental control of morphogenesis. Microbiology. 2000;146 : 1763–1774. 10931884

46. Rocha CR, Schröppel K, Harcus D, Marcil A, Dignard D, Taylor BN, et al. Signaling through adenylyl cyclase is essential for hyphal growth and virulence in the pathogenic fungus Candida albicans. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12 : 3631–3643. 11694594

47. Bockmühl DP, Krishnamurthy S, Gerads M, Sonneborn A, Ernst JF. Distinct and redundant roles of the two protein kinase A isoforms Tpk1p and Tpk2p in morphogenesis and growth of Candida albicans. Mol Microbiol. 2001;42 : 1243–1257. 11886556

48. Saputo S, Chabrier-Rosello Y, Luca FC, Kumar A, Krysan DJ. The RAM network in pathogenic fungi. Eukaryot Cell. 2012;11 : 708–717. doi: 10.1128/EC.00044-12 22544903

49. Cantero PD, Ernst JF. Damage to the glycoshield activates PMT-directed O-mannosylation via the Msb2-Cek1 pathway in Candida albicans. Mol Microbiol. 2011;80 : 715–725. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07604.x 21375589

50. Badis G, Chan ET, van Bakel H, Pena-Castillo L, Tillo D, Tsui K et al. A library of yeast transcription factor motifs reveals a widespread function for Rsc3 in targeting nucleosome exclusion at promoters. Mol Cell. 2008;32 : 878–887. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.11.020 19111667

51. Du H, Guan G, Xie J, Sun Y, Tong Y, Zhang L, et al. Roles of Candida albicans Gat2, a GATA-type zinc finger transcription factor, in biofilm formation, filamentous growth and virulence. PLoS One. 2012;7: e29707. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029707 22276126

52. Nobile CJ, Mitchell AP. Regulation of cell-surface genes and biofilm formation by the C. albicans transcription factor Bcr1p. Curr Biol. 2005;15 : 1150–1155. 15964282

53. Fu Y, Filler SG, Spellberg BJ, Fonzi W, Ibrahim AS, Kanbe T, et al. Cloning and characterization of CAD1/AAF1, a gene from Candida albicans that induces adherence to endothelial cells after expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Infect Immun. 1998;66 : 2078–2084. 9573092

54. Bertram G, Swoboda RK, Gooday GW, Gow NA, Brown AJ. Structure and regulation of the Candida albicans ADH1 gene encoding an immunogenic alcohol dehydrogenase. Yeast. 1996;12 : 115–127. 8686375

55. Martin R, Moran GP, Jacobsen ID, Heyken A, Domey J, Sullivan DJ, et al. The Candida albicans-specific gene EED1 encodes a key regulator of hyphal extension. PLoS One. 6:e18394. Mol Microbiol. 2011;53 : 969–983. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018394 21512583

56. Bonhomme J, Chauvel M, Goyard S, Roux P, Rossignol T, d'Enfert C. Contribution of the glycolytic flux and hypoxia adaptation to efficient biofilm formation by Candida albicans. Mol Microbiol. 2011;80 : 995–1013. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07626.x 21414038

57. Kadosh D, Johnson AD. Rfg1, a protein related to the Saccharomyces cerevisiae hypoxic regulator Rox1, controls filamentous growth and virulence in Candida albicans. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21 : 2496–2505. 11259598

58. Zordan RE, Miller MG, Galgoczy DJ, Tuch BB, Johnson AD. Interlocking transcriptional feedback loops control white-opaque switching in Candida albicans. PLoS Biol. 2007;5: e256 17880264

59. Lohse MB, Hernday AD, Fordyce PM, Noiman L, Sorrells TR, Hanson-Smith V, et al. Identification and characterization of a previously undescribed family of sequence-specific DNA-binding domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110 : 7660–7665. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1221734110 23610392

60. Pérez JC, Kumamoto CA, Johnson AD. Candida albicans commensalism and pathogenicity are intertwined traits directed by a tightly knit transcriptional regulatory circuit. PLoS Biol. 2013;11: e1001510. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001510 23526879

61. Cao F, Lane S, Raniga PP, Lu Y, Zhou Z, Ramon K, et al. The Flo8 transcription factor is essential for hyphal development and virulence in Candida albicans. Mol Biol Cell. 2006; 17 : 295–307. 16267276

62. Du H, Guan G, Xie J, Cottier F, Sun Y, Jia W, et al. The transcription factor Flo8 mediates CO2 sensing in the human fungal pathogen Candida albicans. Mol Biol Cell. 2012; 23 : 2692–2701. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E12-02-0094 22621896

63. Bruno VM, Kalachikov S, Subaran R, Nobile CJ, Kyratsous C, Mitchell AP. Control of the C. albicans cell wall damage response by transcriptional regulator Cas5. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2: e21. 16552442

64. Bauer J, Wendland J. Candida albicans Sfl1 suppresses flocculation and filamentation. Eukaryot Cell. 2007;6 : 1736–1744. 17766464