-

Články

- Časopisy

- Kurzy

- Témy

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

A Large-Scale Functional Analysis of Putative Target Genes of Mating-Type Loci Provides Insight into the Regulation of Sexual Development of the Cereal Pathogen

The production of sexual propagules via a self-fertile mating strategy in Fusarium graminearum, an important cereal pathogen, is essential for overwintering and dissemination during the recurrent disease cycle caused by this fungus. Genome-wide microarray analyses allow the identification of gene sets that are regulated by the mating-type (MAT) loci, which is a master regulator of sexual reproduction in F. graminearum. By employing in-depth and high-throughput functional analyses, the current study provides novel insight into our understanding of the regulation of sexual developmental processes by the MAT loci. MAT genes, which are located at two linked MAT loci, play important roles in even the late stages of sexual development by controlling regulatory pathways involving several sexual-specific transcription factors and putative RNA interference regulators. This study could be significant both practically and fundamentally because of the ecological impact of sexual reproduction by F. graminearum during disease development in the field.

Published in the journal: A Large-Scale Functional Analysis of Putative Target Genes of Mating-Type Loci Provides Insight into the Regulation of Sexual Development of the Cereal Pathogen. PLoS Genet 11(9): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1005486

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1005486Summary

The production of sexual propagules via a self-fertile mating strategy in Fusarium graminearum, an important cereal pathogen, is essential for overwintering and dissemination during the recurrent disease cycle caused by this fungus. Genome-wide microarray analyses allow the identification of gene sets that are regulated by the mating-type (MAT) loci, which is a master regulator of sexual reproduction in F. graminearum. By employing in-depth and high-throughput functional analyses, the current study provides novel insight into our understanding of the regulation of sexual developmental processes by the MAT loci. MAT genes, which are located at two linked MAT loci, play important roles in even the late stages of sexual development by controlling regulatory pathways involving several sexual-specific transcription factors and putative RNA interference regulators. This study could be significant both practically and fundamentally because of the ecological impact of sexual reproduction by F. graminearum during disease development in the field.

Introduction

Fusarium graminearum, a homothallic (self-fertile) ascomycetous fungus, causes serious diseases (e.g., Fusarium head blight) in major cereal crops, and produces several mycotoxins in diseased cereals [1]. Recently, this species was defined as a member of the F. graminearum species complex, which consists of more than 16 phylogenetically distinct species found worldwide [2–7]. To complete the recurrent cycle of cereal diseases, F. graminearum produces sexual progeny (ascospores) on cereal debris as overwintering propagules [8]. The sexual reproduction of F. graminearum is controlled by master regulators called mating-type (MAT) loci [9, 10]. Unlike their heterothallic relatives, F. graminearum carries two closely linked MAT loci (MAT1-1, MAT1-2). A single nucleus contains individual MAT genes in a structural organization (MAT1-1-1, MAT1-1-2, MAT1-1-3 at the MAT1-1 locus; MAT1-2-1 at the MAT1-2 locus) similar to that of other Sordariomycetes (e.g., Neurospora crassa, Podospora anserina, Sordaria macrospora) [9, 10]. All of the MAT genes encode transcription factors that carry conserved DNA-binding motifs called an alpha box (MAT1-1-1), an HMG-box domain (MAT1-1-3, MAT1-2-1), and a PHP domain (MAT1-1-2) [9, 10].

The importance of individual MAT transcripts and MAT loci for sexual development has been intensively studied in F. graminearum, but their functional requirement is not conserved among other fungal species. All of the four individual MAT genes at the MAT loci are essential for sexual development in F. graminearum [11–14], whereas SmtA-1 and SmtA-3 (comparable to MAT1-1-1 and MAT1-1-3, respectively) are dispensable for fruiting body (perithecium) formation in homothallic S. macrospora [15]. In heterothallic species, MAT1-1-2 is essential for perithecium formation in P. anserina, but has a redundant function together with MAT1-1-3 in N. crassa [15]. The phenotypic changes caused by MAT deletions and gene expression patterns in F. graminearum strongly suggest that MAT genes are involved in both the early and late stages of sexual development [13, 14]. In contrast, the prominent roles of MAT genes in heterothallic species are to maintain the sexual identity of cells that express the opposite MAT gene for mating (i.e., controlling sexual compatibility) and to regulate pheromone-mediated signaling pathways. Recently, an additional transcript (MAT1-2-3) with no DNA-binding motif was identified in the MAT1-2 locus [16], but its role(s) in sexual development is not essential in F. graminearum [14].

MAT transcriptional factors may control the transcriptional expression of downstream genes that are necessary for sexual development in filamentous fungi. Several transcriptional profiling analyses have been performed to identify MAT loci target genes that are differentially expressed in fungal strains lacking MAT genes during sexual development [17–20]. However, the function and related regulatory pathways of MAT-target genes have not been sufficiently elucidated to allow a comprehensive understanding of sexual development under the control of the MAT loci; only homology-based functional categorization and limited information regarding gene function (such as pheromone/receptor genes) are available. Very recently, putative target genes of a fungal mating-type gene (MAT1-1-1) carrying a DNA binding alpha box domain were identified by a genome-wide search using chromatin immunoprecipitation combined with next-generation sequencing (ChIP-seq) in Penicillium chrysogenum, but only a limited number of target genes were functionally characterized [21]. In F. graminearum, genome-wide transcriptional analyses during perithecium development have been also performed using microarrays [22] and RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) technology [23], but the functions of most of the highly expressed genes remain unclear.

Despite intensive investigation of MAT genes in filamentous fungi, many questions regarding sexual developmental processes regulated by MAT genes remain unanswered. Various cellular and developmental events occur during sexual reproduction in ascomycetes: ascogonium formation, fertilization, nuclear migration and proliferation in ascogonium, nuclear recognition and fusion in dikaryotic hyphae, meiosis, and ascus/ascospore formation. However, little is known about the specific roles of MAT genes in these sexual stages, particularly those after fertilization, although pheromone/receptor-mediated fertilization under control of MAT is well-established in heterothallic species. In homothallic species, the function of MAT loci that are present within a single nucleus are less known compared to those in heterothallic species; even the mechanism by which MAT controls the mating process remains unclear.

Homothallic F. graminearum is an ideal species for exploring these unanswered questions for several reasons described below. The presence of both MAT1-1 and MAT1-2 loci in a single nucleus provides a good model system for investigating the roles of both loci after fertilization (e.g., nuclear fusion, meiosis, perithecium maturation), which requires two parental strains of the opposite mating types in heterothallic species. The capacity of F. graminearum to outcross and self-cross [11] suggests that it has gene regulatory mechanisms for sexual development that are identical to those of heterothallic ascomycetes. Unlike S. macrospora, F. graminearum, requires all of the transcripts at both MAT loci for sexual development [14], which makes the effects of MAT deletions on the expression and function of MAT target genes more evident. In addition, F. graminearum can be molecularly manipulated to allow high-throughput gene deletions [24] and genetic analyses [11]. Finally, the production of sexual progeny is ecologically important for disease development by F. graminearum, because its sexual cycle predominates in the field, which makes the current study significant both practically and fundamentally.

To explore the regulatory mechanisms controlled by MAT genes in F. graminearum, we performed a large-scale study of the target genes of two MAT loci using several strategies including genome-wide transcriptional profiling in various genetic backgrounds, protein binding microarray analysis, in-depth quantitative real-time PCR, and high-throughput gene deletions. The results of this study combined with previous reports provide an insight that allows a comprehensive understanding of the sexual developmental processes under the control of the MAT loci in F. graminearum.

Results

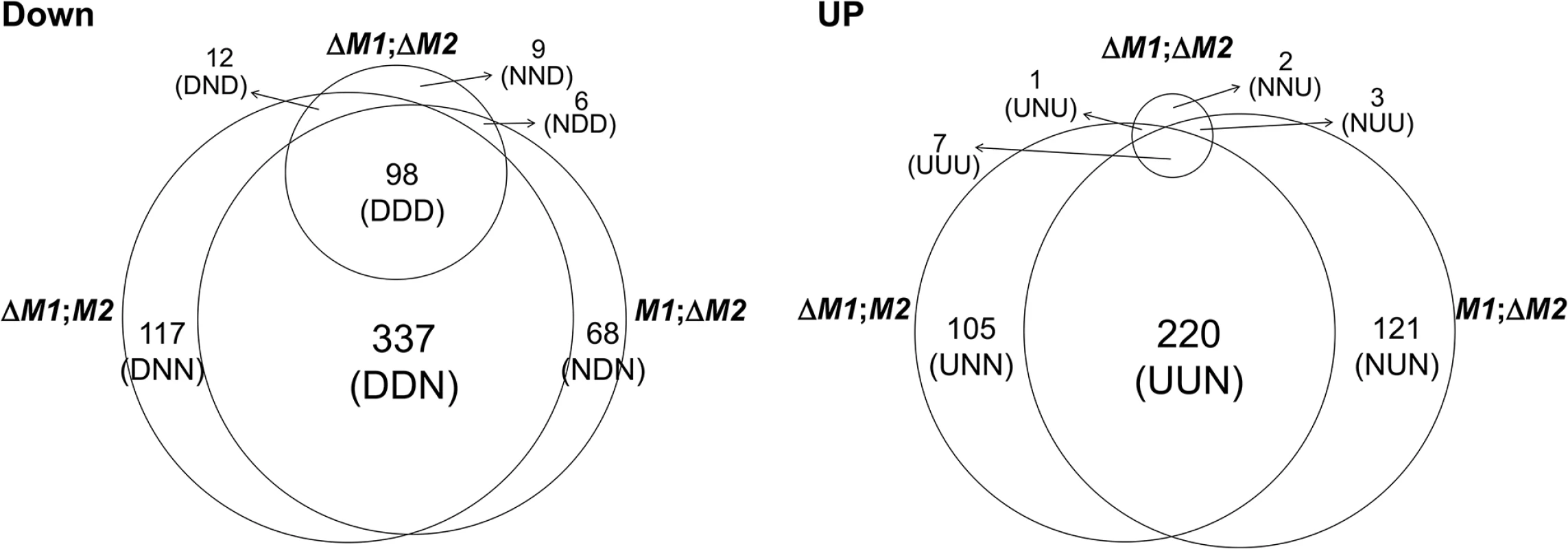

Identification of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in each transgenic strain

For the microarrays, we used four transgenic strains that were derived from the self-fertile wild-type (WT) strain (Z3643). Three strains, designated ΔMAT1-1, ΔMAT1-2, and ΔMAT1-1;ΔMAT1-2, contained different deletions of the two MAT loci (MAT1-1, MAT1-2), and one strain (OM2) overexpressed the MAT1-2-1 allele (for details, see S1 Text and S1–S3 Figs). To identify genes that were regulated by the MAT loci during sexual development, genome-wide microarray analysis was performed using total RNA extracted from mycelia and/or perithecial initials of three MAT-deletion strains, OM2, and their WT progenitor (Z3643). Analysis of the transcriptional profiles revealed a total of 1,245 genes that were differentially regulated by ≥ 2-fold in all of the transgenic strains compared to Z3643. Among these, 1,106 (647 downregulated, 459 upregulated) were differentially regulated in the three MAT-deletion strains (ΔMAT1-1, ΔMAT1-2, ΔMAT1-1;ΔMAT1-2), and 187 (177 downregulated, 10 upregulated) were in OM2 (Fig 1, S1 Table). All of the DEGs identified in the three MAT-deletion strains could be categorized into 14 groups according to their expression patterns in each MAT-deletion background (Fig 1, S1 Table). Of the 647 genes that were downregulated compared to WT, 522 (80.7%) were in either or both ΔMAT1-1 and ΔMAT1-2, but not in ΔMAT1-1;ΔMAT1-2. Among these, 337 were downregulated in both ΔMAT1-1 and ΔMAT1-2, but were not significantly changed in ΔMAT1-1;ΔMAT1-2 (designated DDN, where the first D means downregulated in ΔMAT1-1, the second D is for the downregulation in ΔMAT1-2, and N means no change in ΔMAT1-1;ΔMAT1-2), 117 were downregulated in only ΔMAT1-1 (DNN), and 68 were downregulated in only ΔMAT1-2 (NDN). The remaining 125 genes were downregulated in ΔMAT1-1;ΔMAT1-2, regardless of the differential regulation in either ΔMAT1-1 or ΔMAT1-2, among which 98 (78.4%) were DDD-type (Fig 1). Among the upregulated genes, most (97.2%) were present in either or both ΔMAT1-1 and ΔMAT1-2, but not in ΔMAT1-1;ΔMAT1-2; 220, 105, and 121 genes were UUN-, UNN-, and NUN-type, respectively (Fig 1). Most of the DEGs identified in OM2 were downregulated, among which 15 were also downregulated and 30 were also upregulated in the MAT-deletion strains (S1 Table). Four of the ten genes upregulated in OM2 were also downregulated in the MAT-deletion strains (S1 Table). MAT1-2-1 was NDD-type and was upregulated in OM2, and two MAT1-1 transcripts (MAT1-1-2, MAT1-1-3) were the DND-type, and were unchanged in OM2.

Fig. 1. Number of genes expressed differentially in the F. graminearum strains deleted for the MAT1-1 locus (0394M1;M2), MAT1-2 locus (M1; ΔM2), and both MAT1-1 and MAT1-2 loci (ΔM1; Δ M2) compared to their wild-type progenitor Z3643.

DOWN, downregulated genes; UP, upregulated genes. The numbers of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in each expression category are indicated above the category designations in parentheses. Abbreviations for DEGs with three characters: U, upregulated, D; downregulated; N, no change. The first, second, and third characters represent the expression pattern in the ΔMAT1-1, ΔMAT1-2, and ΔMAT1-1;ΔMAT1-2 strains, respectively, compared to the Z3643 strain. In addition, 729 DEGs (325 downregulated, 404 upregulated) were identified in the two MAT deletion strains (ΔMAT1-1 and ΔMAT1-2) compared to the MAT null strain (ΔMAT1-1;ΔMAT1-2) (S4 Fig, S2 Table). In total, 87 of the 101 NNU-type genes (unchanged in ΔMAT1-1 or ΔMAT1-2, but upregulated in WT compared to ΔMAT1-1;ΔMAT1-2) overlapped with the DDD-type genes that were identified in comparison with WT (S2 Table).

Functional categorization (annotation) of DEGs

The GO analysis revealed that several Biological Process categories were enriched among the DDN-, DNN-, and NDN-type genes, including various types of metabolism, and developmental processes. Among the genes (UNN, UUN, NUN) upregulated in the MAT-deletion strains were enriched the categories of carbohydrate metabolism, developmental processes involved in sporulation, cellular response to chemical stimuli, and cell wall organization. Most of the cellular components categories enriched among these groups were fungal cell wall, plasma membranes, and extracellular (S3 Table). The DDD-type genes were poorly matched to the GO-terms; only those involved in developmental processes (e.g., regulation of cell morphogenesis and response to stimuli), and organic hydroxyl compound metabolism (including the polyketide biosynthesis for perithecial pigment) categories were enriched in this group (S3 Table). Among the genes that were downregulated in OM2, the categories of metabolism for lipid and nitrogen compounds were enriched. (S3 Table).

In addition to the genes enriched for GO terms, 21 genes that might be involved in the cellular processes (e.g., cell fusion, nuclear fusion, cell division, chromosome partitioning) required for sexual development were identified among the DEGs (S4 Table); the expression of most of these was unchanged in ΔMAT1-1;ΔMAT1-2 (XXN).

Confirmation of differential gene expression in MAT-deletion strains

A total of 58 DEGs identified in this study were analyzed using quantitative real-time PCR in MAT-deletion strains at the perithecial induction stage to confirm that their differential expression was caused by each MAT deletion. The expression patterns of 42 of the 58 genes compared in the three MAT-deletion strains and WT were consistent with the microarray results (S5 Table). The other 16 genes were also differentially expressed, but their patterns in one of three MAT-deletion strains were not consistent with the qPCR data. Among these, eight genes that were identified as DDN-type in the microarrays, exhibited expression that was downregulated almost two-fold in ΔMAT1-1;ΔMAT1-2 compared to WT, and were confirmed as DDD-type using qPCR. Previous studies confirmed that an additional eight genes were downregulated in either ΔMAT1-2 or both ΔMAT1-1 and ΔMAT1-2 strains by Northern blot analysis [17, 25].

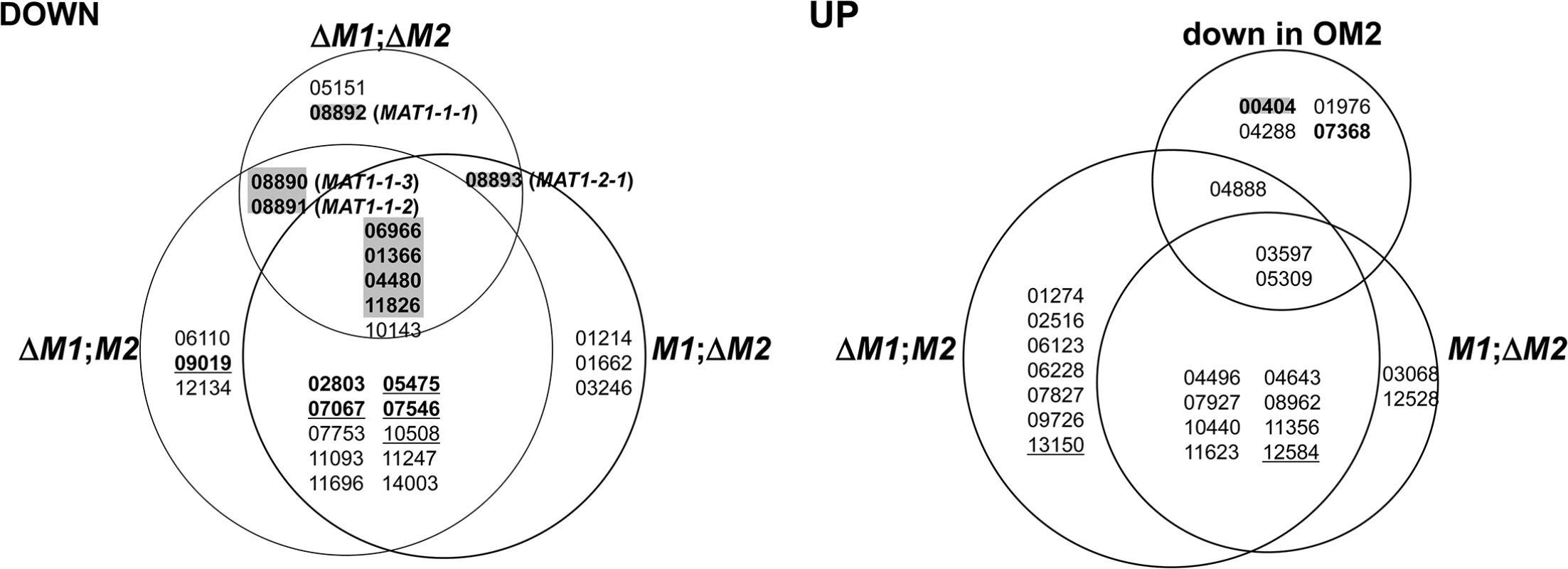

Transcription factors among the DEGs

A total of 50 transcription factor (TF) genes (6.9% of the total TFs in the F. graminearum genome) [24] were identified among the DEGs in the current study (Fig 2). TF genes with a specific and essential function for sexual development in F. graminearum, which were identified based on phenotypic changes after gene deletions [24], were only enriched among gene groups that were downregulated in ΔMAT1-1;ΔMAT1-2 (DND, NDD, NND, DDD). All of the sexual development-specific TFs, other than the MAT genes themselves, were DDD-type. The TFs belonging to other gene groups, whose expression levels were unchanged in ΔMAT1-1;ΔMAT1-2 (DDN, DNN, NDN), were either dispensable for sexual development (ten TFs), involved in pleiotropic phenotypes (i.e. involved in sexual development and other traits; four TFs), or involved in traits other than sexual development (two TFs; Fig 2). In contrast, none of the TFs that were specific to sexual development were identified among the 20 TFs upregulated in the MAT-deletion strains; only 1 TF gene deletion proved lethal. Among the four TFs downregulated in OM2, only one TF (FGSG_00404) was sexual-specific in the Z3639 strain in a previous study [24], but was not in Z3643 in the current study. The remaining TFs were dispensable or were involved in sexual development along with other trait (zearalenone production) (FGSG_07368) (Fig 2).

Fig. 2. Genes encoding the transcription factors differentially expressed in the F. graminearum strains deleted for the MAT1-1 locus (ΔM1;M2), MAT1-2 locus (M1;ΔM2), both MAT1-1 and MAT1-2 loci (ΔM1;ΔM2), and overexpressing MAT1-2-1 (OM2).

DOWN, downregulated genes; UP, upregulated genes. The gene expression categories in the Venn diagrams are the same as those in Fig 1. The numbers in each category indicate the gene ID (FGSG ID) in the F. graminearum genome database. Based on the phenotypic changes by gene deletions [23], the F. graminearum locus IDs (FGSG_) on a gray background indicate the genes specific in function to sexual development, IDs in bold and underline are for those involved in sexual development and other traits, IDs in bold are for those are involved in the traits other than sexual development, and underlined IDs are for those probably lethal.

Identification of gene clusters for secondary metabolites (SMs) among the DEGs

We focused on the expression profiling of genes involved in secondary metabolism since it has been known that secondary metabolism and sexual development are linked in filamentous fungi. To identify SM genes among the DEGs, they were compared against members of the 67 tentative SM gene clusters in F. graminearum [26]. Gene member(s) belonging to 22 SM clusters were identified in the DEGs from the MAT-deletion strains or OM2 (S6 Table); however, only 6 SM clusters included DEGs that encoded key (signature) enzymes. Among these, members of two polyketide synthase (PKS) gene clusters were downregulated in the MAT-deletion strains: PKS3 (along with four additional genes), which is responsible for the biosynthesis of dark perithecial pigment, and PKS7 (with one tailoring gene), whose chemical product has not yet been identified; these were DDD - and DDN-type, respectively. Two non-ribosomal peptide synthetase genes (NPS10, a NPS-like gene) for unknown metabolites were also identified. In addition to these key enzyme genes, those that encoded either tailoring enzymes or transporters belonging to other PKS clusters (PKS2, PKS14, PKS15, PKS17 for unknown polyketide compounds), an NPS1 cluster for a siderophore (malonichrome) [27], and a butenolide cluster were identified among the DEGs (S6 Table).

Expression of genes identified previously in F. graminearum among the DEGs

A total of 169 DEGs (13.6%) identified in this study overlapped with the 2,064 genes identified previously as sexual development-specific in the F. graminearum PH-1 strain, and whose transcripts were only detected during perithecium formation [22]. The genes downregulated in ΔMAT1-1;ΔMAT1-2 (i.e. NND-, NDD-, DND-, DDD-type) overlapped at a higher frequency (43 of 125; 34.4%) than those downregulated in both or either ΔMAT1-1 and ΔMAT1-2 (DDN, DNN, NDN) (76 of 522; 14.6%) (S7 Table).

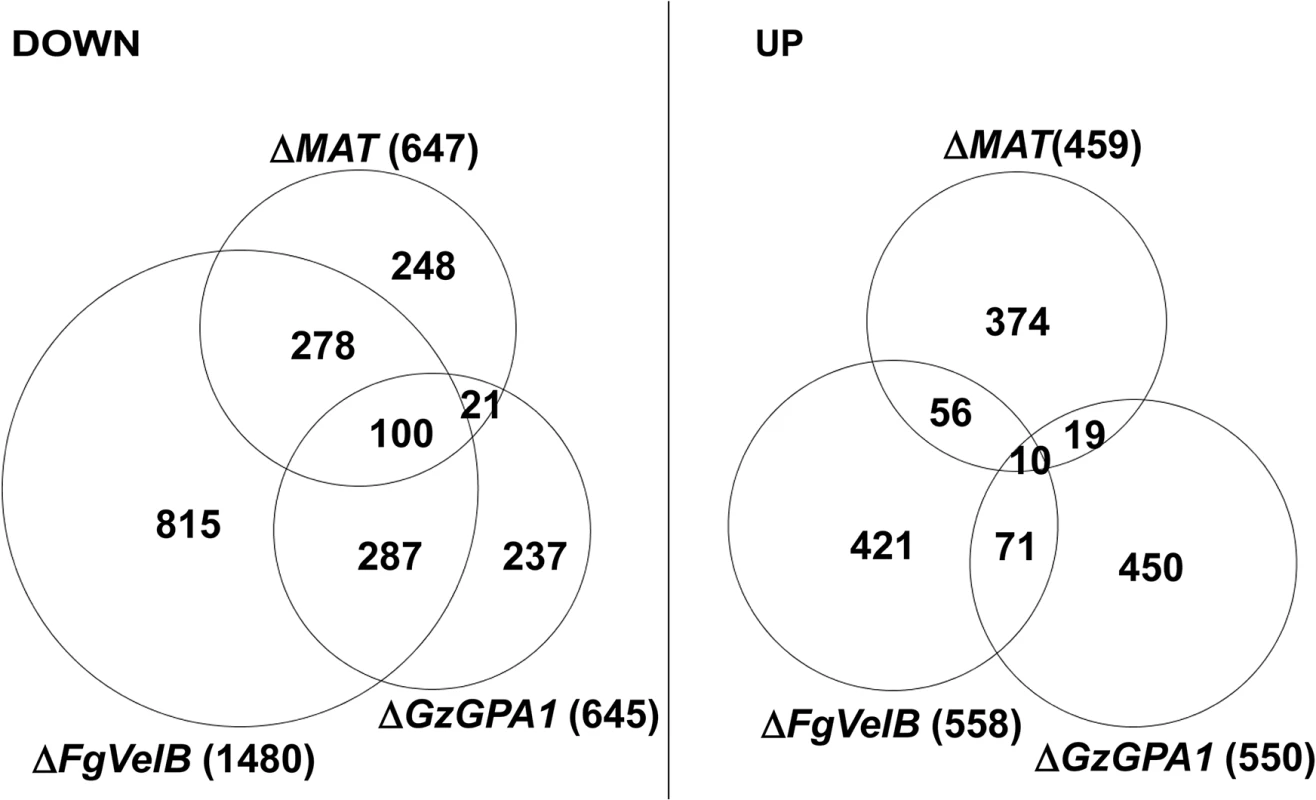

The DEGs identified in this study were also compared to those from the F. graminearum strains lacking FgVelB or GzGPA1, both of which are self-sterile [28, 29]. More than half of the genes (378 of 647; 58.4%) that were downregulated in the MAT-deletion strains overlapped with those in F. graminearum ΔFgVelB (Fig 3, S8 Table). In addition, 121 genes (18.7%) downregulated in the MAT-deletion strains overlapped with those in the ΔGzGPA1 strain, among which 100 (82.6%) were also DEGs in the ΔFgVelB strain (Fig 3, S8 Table). Interestingly three MAT genes [MAT1-1-3 (FGSG_08890), MAT1-1-2 (FGSG_08891), and MAT1-2-1 (FGSG_08893)], and one MAT gene [MAT1-1-3 (FGSG_08890)] were downregulated in the ΔFgVelB [28] and ΔGzGPA1 [29] strains, respectively.

Fig. 3. Number of DEGs in the F. graminearum strains lacking the individual MAT or both MAT loci (ΔMAT) overlapped with those from the ΔFgVelB and ΔGzGPA1 strains, respectively.

DOWN, downregulated genes; UP, upregulated genes. The numbers of total DEGs in each category are indicated in parentheses next to the fungal strains. Surprisingly, only a small number of DEGs overlapped with DEGs in S. macrospora strains lacking MAT genes. Specifically, 19 DEGs overlapped with 311 genes regulated exclusively in ΔSmtA-2 (ΔMAT1-1-2), 26 DEGs corresponded to 520 genes regulated in both ΔSmtA-1 and ΔSmtA-2 [15], and 6 DEGs overlapped with 80 genes from ΔSmta-1 (ΔMAT1-2) [19] (S9 Table).

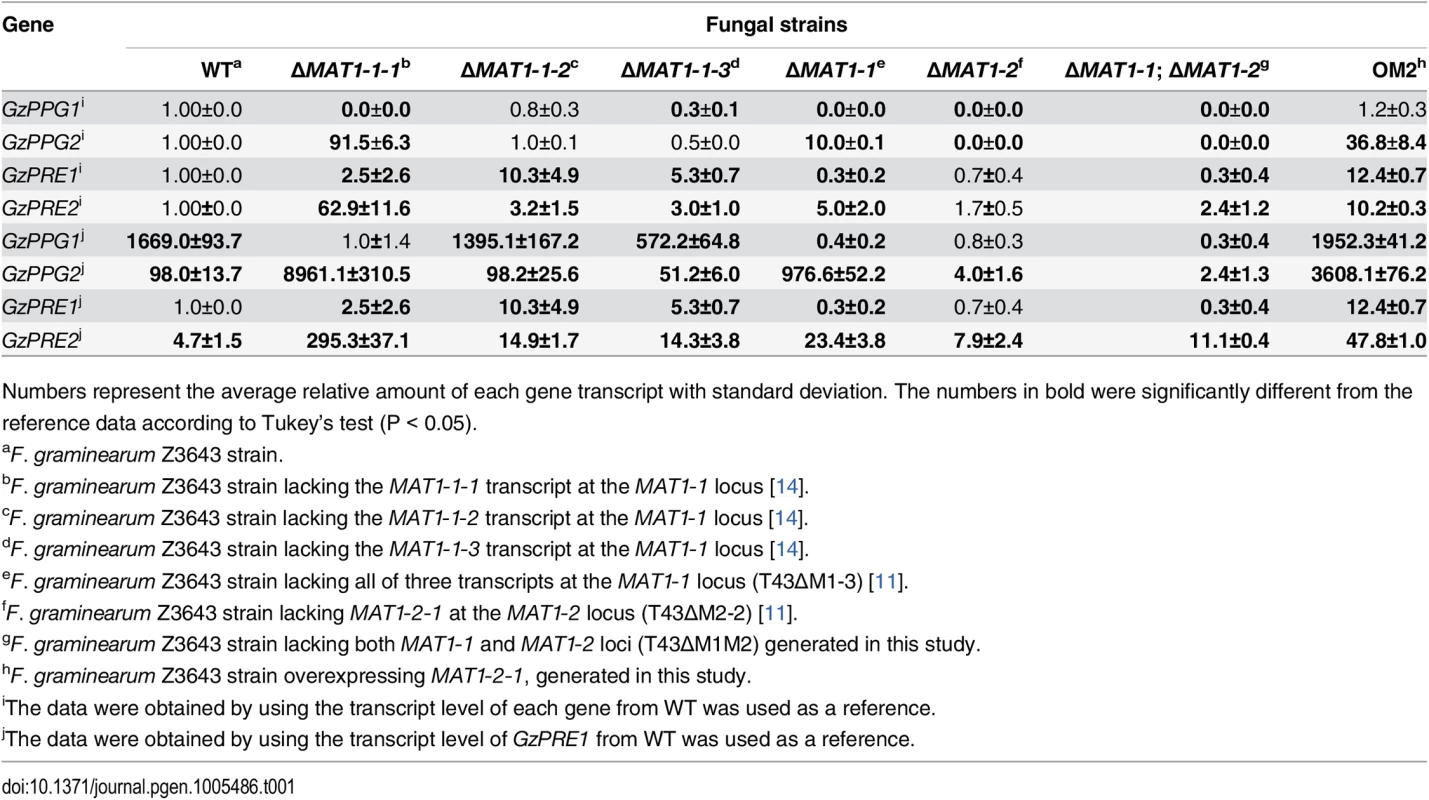

Transcriptional expression of genes encoding pheromone precursors and receptors

To assess how the MAT loci regulate the expression of genes encoding pheromones (GzPPG1, GzPPG2) and their cognate receptors (GzPRE1, GzPRE2) during the early stage of perithecial induction (3 days after the removal of the aerial mycelia on carrot agar), qPCR was used to compare the transcript levels of each gene in the fungal strains used in microarray analysis, as well as in those lacking individual genes (MAT1-1-1, MAT1-1-2, MAT1-1-3) in the MAT1-1 locus (Table 1). Because northern blotting previously confirmed that all four genes were only expressed in the WT strain during sexual development [30], we used the transcript level of each gene in WT, or the weakest expression level in GzPRE1 as references to evaluate the effects of MAT deletion or overexpression (Table 1). The expression of GzPPG1 was significantly reduced in all of the MAT-deletion strains examined compared to WT, with the exception of ΔMAT1-1-2. Because of the relatively high abundance of the GzPPG1 transcript compared to other genes in WT, this suggests that GzPPG1 is highly expressed only in the WT and ΔMAT1-1-2 strains, but not in a MAT-locus-specific manner. In contrast, GzPPG2 expression was reduced in the ΔMAT1-2 and MAT-null strains, but increased dramatically in the strain lacking the entire MAT1-1 locus (ΔMAT1-1), and that lacking only the MAT1-1-1 gene at the MAT1-1 locus. This suggests that GzPPG2 is only expressed in the WT and ΔMAT1-1 strains, and therefore exhibits a MAT1-2-locus-specific expression pattern, consistent with our previous study [30]. GzPRE1 was downregulated in both the ΔMAT1-1 and MAT-null strains, but was expressed at comparable levels in the ΔMAT1-2 and WT strains, suggesting a MAT1-1-locus-specific expression. However, the upregulation of GzPRE1 in strains lacking individual MAT1-1 transcripts was surprising, although most of the upregulated transcript were expressed at levels that were weaker than or similar to GzPRE2 in WT. In contrast, GzPRE2 was upregulated in all of the MAT-deletion strains except for ΔMAT1-2, suggesting that GzPRE2 was constitutively expressed in all of the strains examined. The effects of ΔMAT1-1-1 on the expression of genes encoding pheromones and their receptors were more dramatic than those of other MAT1-1 gene deletions (ΔMAT1-1-2, ΔMAT1-1-3), with the exception of GzPRE1, suggesting that MAT1-1-1 is the major regulator of the pheromone/receptor system among the three transcripts at the MAT1-1 locus. In addition, the expression of GzPPG2, GzPRE1, and GzPRE2 was upregulated in the OM2 strain (Table 1).

Tab. 1. Relative transcript levels of genes for pheromone precursors and receptors accumulated in the MAT-deletion- and MAT1-2-1-overexprssing-strains of F. graminearum under perithecial induction stage.

Numbers represent the average relative amount of each gene transcript with standard deviation. The numbers in bold were significantly different from the reference data according to Tukey’s test (P < 0.05). Recently, similar gene expression data for pheromone/receptor genes in the MAT-deletion strains were reported by Zheng et al [13]. However, those data cannot be directly compared with those in the current study because they were obtained using RNA samples from aerial hyphae on carrot agar before perithecial induction [13].

Functional characterization of the selected DEGs

To determine the functional requirement of the DEGs identified in the current study during sexual development, we selected 106 DEGs based on their expression patterns and putative functional roles. Then, we deleted each DEG from the F. graminearum Z3643 genome using a targeted gene replacement strategy. Including the 32 DEGs that overlapped with those previously identified as being functionally required for or transcriptionally specific for sexual development and/or other traits (e.g., hyphal growth, toxin production, virulence) in F. graminearum, the results of the functional analysis of a total of 127 DEGs were reported here (S10 Table, S11 Table, Table 2). Based on the phenotypes of the gene deletion strains, 40 genes were responsible for phenotypic changes. Among these, 37 were involved in sexual development alone or together with other traits, and the remaining three were required for phenotypes other than sexual development (S10 Table). Of the 37 genes involved in sexual development, 25 genes were specific to sexual development (Table 2). The phenotypic changes caused by the deletion of these genes were restricted to only sexual developmental processes ranging from the formation of perithecium initials to ascospore discharge; no changes in other traits such as hyphal growth and pigmentation, conidiation, mycotoxin production, and/or virulence were observed. The transgenic strains in which five genes had been individually deleted (FGSG_00404, 04480, 05239, 13708, and 03916) produced no perithecium initials on carrot agar, and those in which each of nine genes were deleted (FGSG_01366, 08320, 11826, 13162, 10742, 08890 [MAT1-1-3], 08891 [MAT1-1-2], 08892 [MAT1-1-1], 08893 [MAT1-2-1]) produced barren perithecia that were smaller in size and/or number than WT and contained no asci/ascospores (S11 Table, Table 2, S5 Fig). By contrast, the remaining 11 genes were not absolutely required for the production of fertile perithecia, but instead, were specifically involved in sexual development. The mutants in which six genes (FGSG_03673, 05151, 07578, 06059, 11962, and 02655 [GzPRE2]) were deleted individually produced lower numbers of mature perithecia, whereas those lacking FGSG_06966 and FGSG_01862 produced larger perithecia, or showed delayed perithecia formation, respectively, compared to WT. The deletion mutants of FGSG_00348, FGSG_02052, and FGSG_09182 (PKS3) produced perithecia that looked similar to those in WT, but exhibited defects at different stages of perithecia maturation (Table 2, S5 Fig).

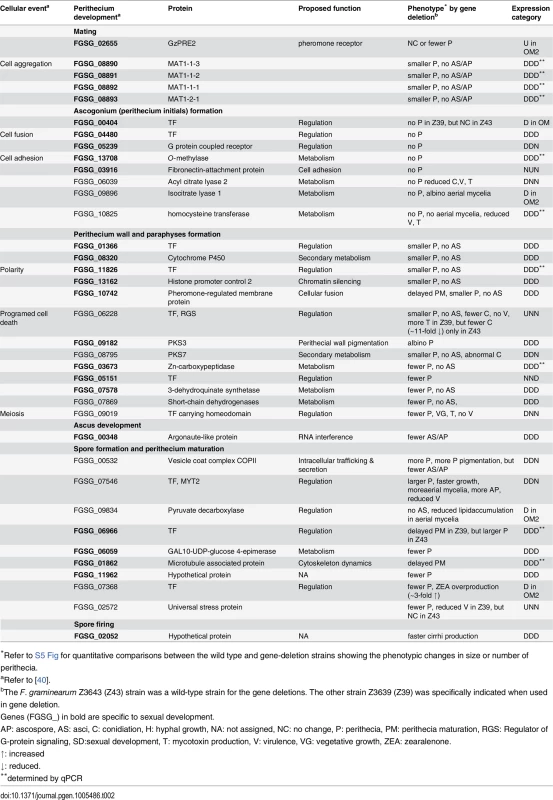

Tab. 2. DEGs required for sexual development in F. graminearum.

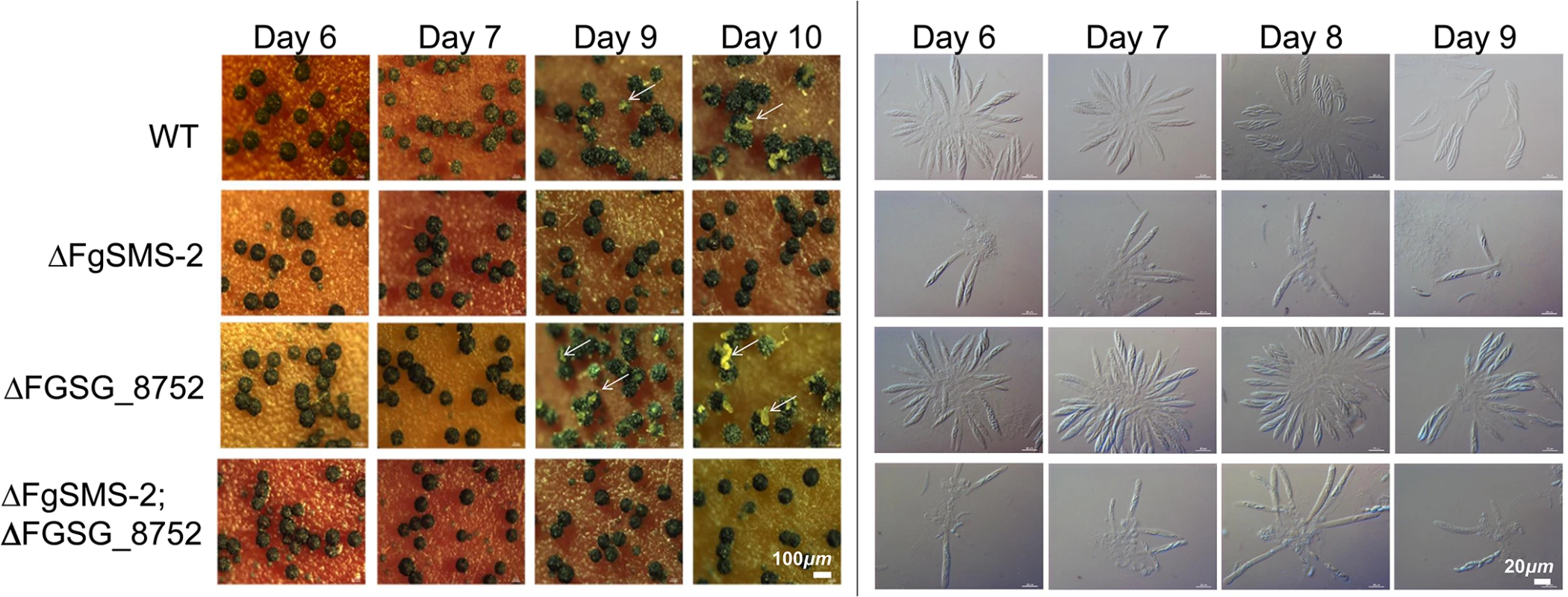

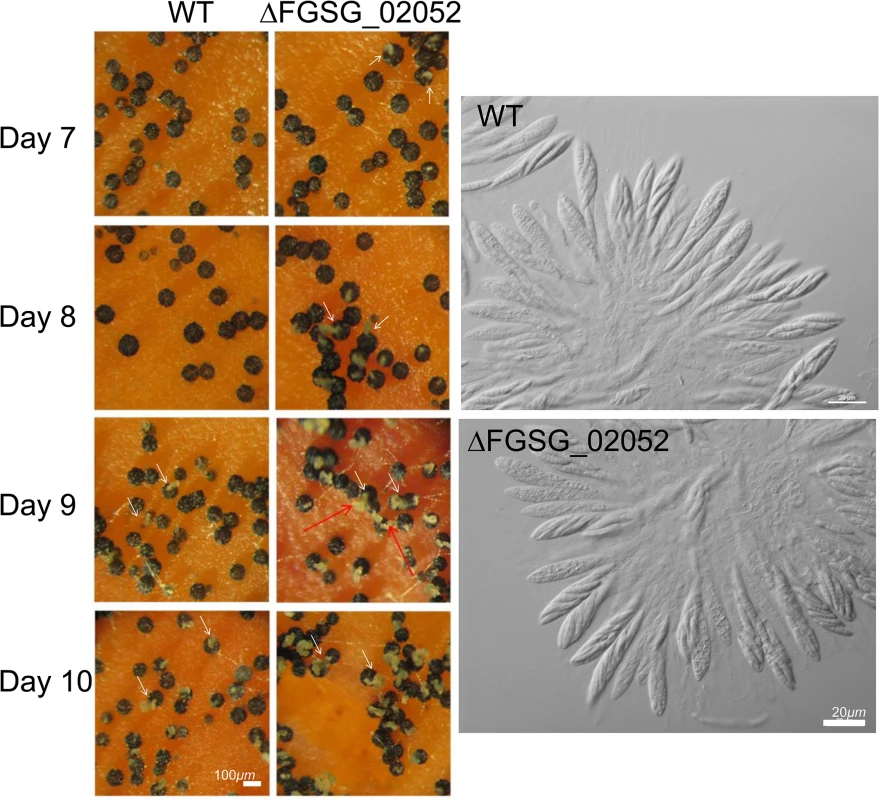

*Refer to S5 Fig for quantitative comparisons between the wild type and gene-deletion strains showing the phenotypic changes in size or number of perithecia. The targeted deletion of FGSG_00348 (designated FgSMS-2) from Z3643, which exhibited sequence similarity to a gene encoding an Argonaute protein known to participate in the RNA interference (RNAi) pathway in Drosophila melanogaster [31] and N. crassa [32], caused no dramatic changes in major traits such as hyphal growth, conidiation, pigmentation, virulence, and perithecia formation in F. graminearum. Unlike the perithecia produced in WT, those in ΔFgSMS-2 produced no cirrhi (ascospores oozing from the perithecia) at the ostiole 10 days after perithecial induction, and contained fewer numbers of asci that were formed at least 2 days later than WT (Fig 4), as previously reported in the Z3639 strain [33]. The germination rate of ascospores was not significantly different from WT. Interestingly, outcrossing the ΔFgSMS-2 strain as a male to the ΔMAT1-2 strain as a female produced incomplete tetrads that mainly carried four ascospores rather than eight, in which the GFP marker did not segregate equally (Fig 5). Furthermore, the outcross between the ΔFgSMS-2 strain (female) and ΔMAT1-2 strain (male) produced asci similar to those in the self-cross of ΔFgSMS-2 strain (Fig 5). qPCR confirmed that FgSMS-2 was specifically expressed at a later stage (7 days after perithecial induction) of sexual development, and was regulated transcriptionally by both MAT loci (S6 Fig). In addition, the expression of three DEGs (FGSG_02877 and belonging to UUN, and 05906 to DDN) was upregulated during sexual development in the ΔFgSMS-2 strain compared to the WT strain, suggesting that FgSMS-2 is involved in the degradation of the mRNAs of these DEGs (S6 Fig). The deletion of another Argonaute-like gene (FGSG_08752) in the F. graminearum genome, which was not differentially regulated by the MAT loci, had no effect on sexual development; even the double deletion of FgSMS-2 and FGSG_08752 yielded an identical phenotype as the ΔFgSMS-2 strain (Fig 4). Unlike ΔFgSMS-2, the strain lacking FGSG_02052 produced cirrhi at least 2 days earlier than WT, but it produced as many normal-looking ascospores as WT (Fig 6).

Fig. 4. Perithecia formation and ascus/ascopore development in the single gene deletion- (ΔFgSMS-2 and ΔFGSG_08752, respectively) and double gene deletion-strains (ΔFgSMS-2;ΔFGSG_8752) grown on carrot agar.

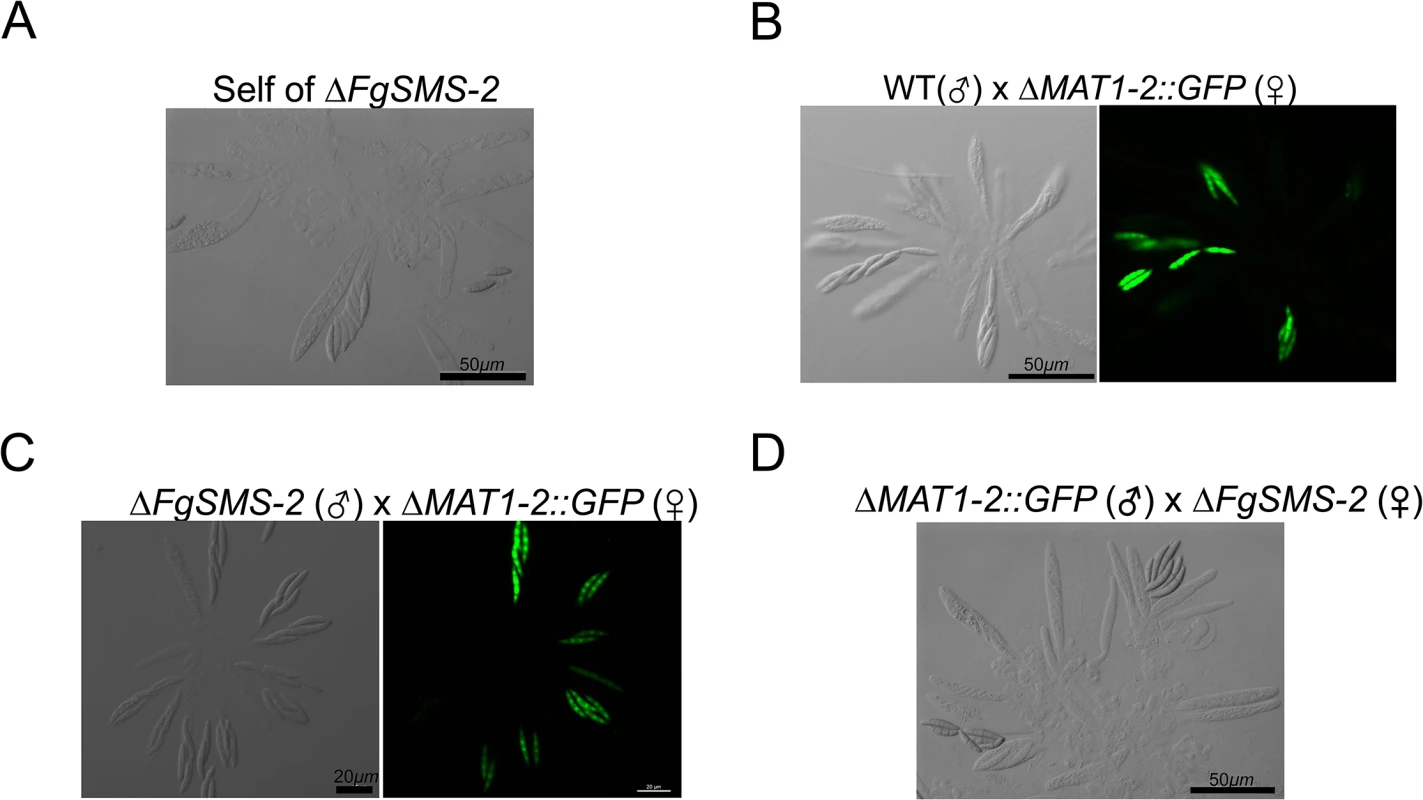

WT: F. graminearum wild-type Z3643 strain. The perithecia formed 6, 7, 9, or 10 days after perithecia induction, and the asci and ascospores that developed within a perithecium were observed through a dissecting microscope (left panels) and differential interference contrast microscope (right panels), respectively. The exuded spore masses called cirrhi from the perithecia in the wild-type and ΔFGSG_08752 strains were indicated by arrows. Scale bars = 100 μm for perithecia and 20 μm for asci/ascospores. Fig. 5. Morphology of asci and ascospores produced in the self-cross of ΔFgSMS-2 (A) and outcrosses between WT(♂) and ΔMAT1-2::GFP(♀) (B), between ΔFgSMS-2(♂) and ΔMAT1-2::GFP(♀) (C), and between ΔMAT1-2::GFP(♂) and ΔFgSMS-2(♀) (D).

WT, the self-fertile F. graminearum wild-type Z3643 strain; ΔFgSMS-2, a transgenic Z3643 strain lacking the FgSMS-2 gene; ΔMAT1-2::GFP, a self-sterile transgenic Z3643 strain where the MAT1-2 locus was replaced with a green fluorescence protein gene (GFP). For the outcrosses, the mycelia of strain acting as a female (♀) were spermatized with conidia of a male-acting strain (♂), as described previously [11]. Only four out of eight ascospores in each ascus fluoresced, as observed by confocal laser microscopy in the outcross between wild-type and ΔMAT2::GFP (B), whereas the outcross of ΔFgSMS-2 to ΔMAT1-2::GFP (C) produced incomplete tetrads, in which the GFP marker did not segregate equally. Fig. 6. Formation of perithecia (left panels) and the morphology of asci and ascospores within a perithecium in the F. graminearum deleted for FGSG_02052 (ΔFGSG_02052) grown on carrot agar.

WT, F. graminearum wild-type Z3643 strain; ΔFGSG_02052, a transgenic Z3643 strain lacking the FGSG_02052 gene. The perithecia formed 7, 8, 9, or 10 days after perithecia induction, and the asci and ascospores that developed within 8-day-old-perithecium were observed through a dissecting microscope (left panels) and differential interference contrast microscope (right panels), respectively. The cirrhi production from the perithecia was indicated by arrows. Scale bars = 100 μm for perithecia and 20 μm for asci/ascospores. Among the 25 genes with sexual development-specific functions, ten (40%; FGSG_04480, 00404, 01366, 11826, 05151, 06966, 08890, 08891, 08892, 08893), including four MAT genes, encode transcription factors, two (FGSG_08320 and 09182) encode SM gene cluster members, and the others are involved in metabolism (FGSG_13708, FGSG_03673, FGSG_07578, FGSG_06059), chromatin silencing (FGSG_13162), cell adhesion (FGSG_03916), signaling (FGSG_05239), cytoskeleton dynamics (FGSG_01862), RNA inference (FGSG_00348), or unknown functions (FGSG_11962 and FGSG_02052) (Table 2). Interestingly, 21 (84%) of the 25 sexual-specific genes were downregulated in ΔMAT1-1;ΔMAT1-2. Only 1 gene (FGSG_05239) among the 31 DDN-type genes examined had a sexual-specific function (Table 2).

In addition, 12 genes (FGSG_00532, 02572, 06039, 06228, 07368, 07546 [MYT2], 07869, 08795, 09019, 09834, 09896 [GzICL1], 10825] were responsible for pleiotropic phenotypes, including defects in sexual development. Three genes, which were not essential for sexual development, were involved in hyphal growth (FGSG_04946) or virulence toward the host plant (FGSG_05906 [FGL1], FGSG_10396]) (Table 2).

Developmental time course expression of DEGs in the WT strain on carrot agar

A total of 37 DEGs identified in the current study were analyzed in the WT strain grown on carrot agar using qPCR to determine the time course of the transcriptional profiles during both the vegetative and sexual stages. Most DEGs examined in the current study (33 of 38) were confirmed as sexual development-specific at the transcriptional level, because they were expressed at higher or lower (for FGSG_05906 only) levels in the WT Z3643 strain under perithecial induction conditions compared to vegetative conditions (S12 Table). Among these, four genes (FGSG_ 05246, FGSG_05847, FGSG_06549, FGSG_01763) could be assumed to be involved in the early stage of perithecium formation, because their expression peaked 3 days after perithecial induction. In contrast, the remaining 28 genes are probably specific to a later stage of sexual development (S12 Table). However, the functional assignment of these genes relies on only a correlation, and needs further confirmation. In our previous study [28], 42 genes that were identified as DEGs in the current study were confirmed to be sexual development-specific in the WT Z3639 strain. Among these, 50% (21 genes) and 28.6% were DDD - and DDN-type, respectively (S8 Table).

When the DEGs in the current study were searched against the transcriptome data obtained from the fungal PH-1 strain at 6 developmental stages during perithecium formation, data revealed that 1,152 DEGs were expressed at these time points [23] (S13 Table). In particular, the transcript accumulation of 72% (87/121) of the XXD-type genes (including DDD, DND, NDD, NND) peaked 96 h after perithecial induction, whereas the expression of 70% of the XXN-type (DDN, DNN, NDN) genes peaked at earlier time points (2, 24, 48, or 72 h; S13 Table). However, the upregulated genes were not enriched at a specific stage. In addition, 45% (54/120) of the genes that were downregulated in OM2 exhibited the highest transcript accumulation at 72 h (Table 3).

Tab. 3. DEGs overlapped with the transcriptomics data during sexual developmental processes, generated by Sikhakolli et al [23]. ![DEGs overlapped with the transcriptomics data during sexual developmental processes, generated by Sikhakolli et al [<em class="ref">23</em>].](https://www.prelekara.sk/media/cache/resolve/media_object_image_small/media/image/436dff7e5496419dc233ed874d2e2104.png)

Refer to S13 Table for details. Identifying a putative binding site for MAT1-2-1 protein using protein binding microarrays (PBM)

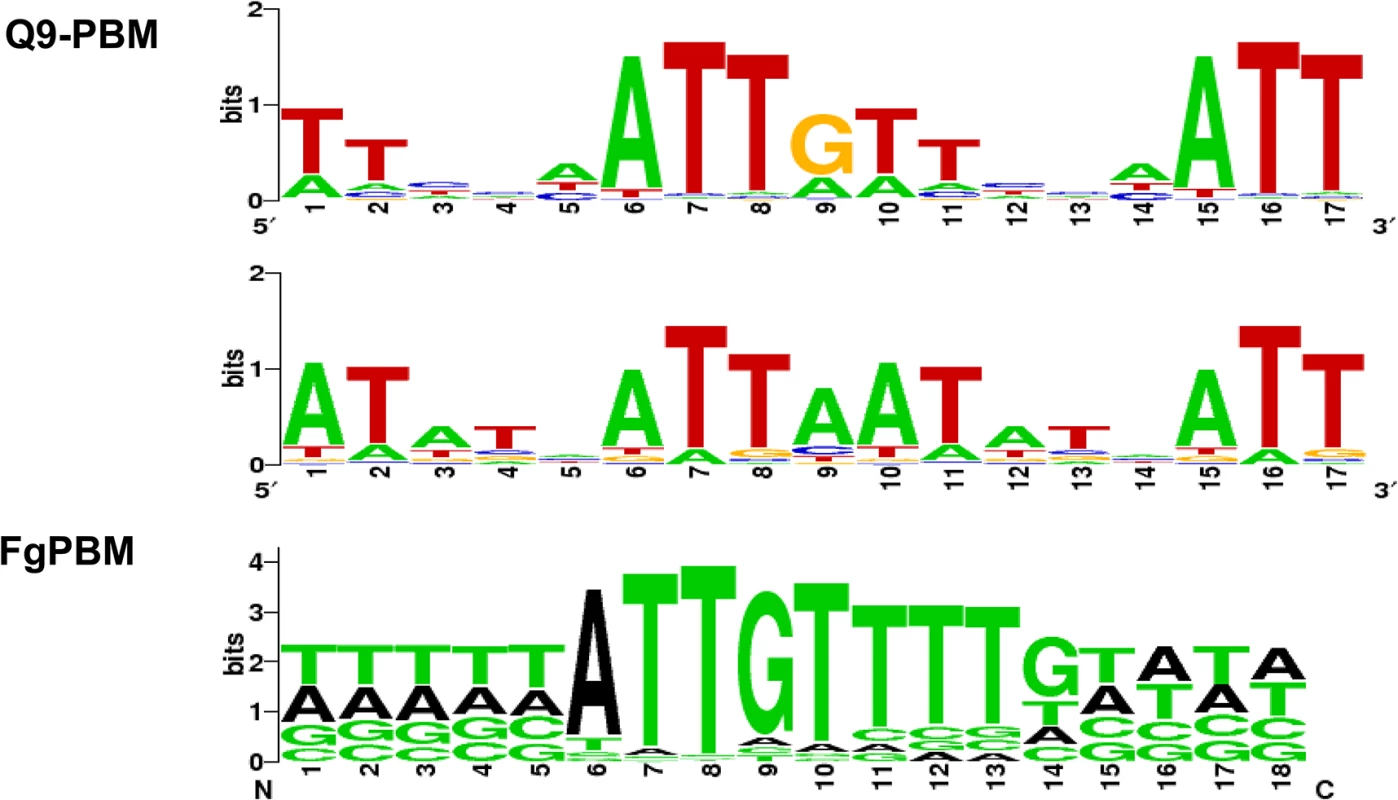

We used PBM technology [34, 35] to identify a putative binding site for the MAT1-2-1 protein (S7 and S8 Figs). Two PBMs (Q9-PBM, FgPBM) were hybridized to the DNA-binding HMG motif of MAT1-2-1, which was fused to DsRed fluorescent protein, and then expressed in E. coli. A comparison of the putative consensus binding sequences identified using both PBM methods indicated that ATTGTT could be the core binding sequence for the HMG domain of MAT1-2-1 (Fig 7), which is complementary to the core-binding element (AACAAT) of the mammalian sex-determining region Y (SRY) or SRY-related HMG box gene (SOX) [36–38].

Fig. 7. The determined consensus binding sequences according to two PBM analyses (Q9-PBM and FgPBM).

The target probes in Q9-PBM (Quadruple 9-mer-Based PBM) are synthesized as quadruples of all possible 9-mer combinations, whereas FgPBM consists of probes designed from the putative promoter region (1,000 bp upstream of the start site of each ORF) of the F. graminearum genome (refer to S2 Text for details). To determine the binding motifs, two independent linear models were applied in the deep and heavy right tail region (refer to S2 Text and S7 Fig). Here, two of the most significant binding motifs identified by Q9-PBM are shown, among which the ATTGTT motif was also identified by FgPBM. Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) revealed that the quadruple sequences of the identified motifs (ATTAAT and ATTGTT) had binding activities for the MAT1-2-1 HMG box domain (S9A Fig). The promoter regions of three genes (FGSG_04946, FGSG_08467 and FGSG_06480) could bind to MAT1-2-1, but their binding activities were relatively weak (S9B Fig). Experimental details and discussion from the PBM and EMSA analyses were described in S2 Text.

Transcriptional networks of the genes regulated by the MAT loci

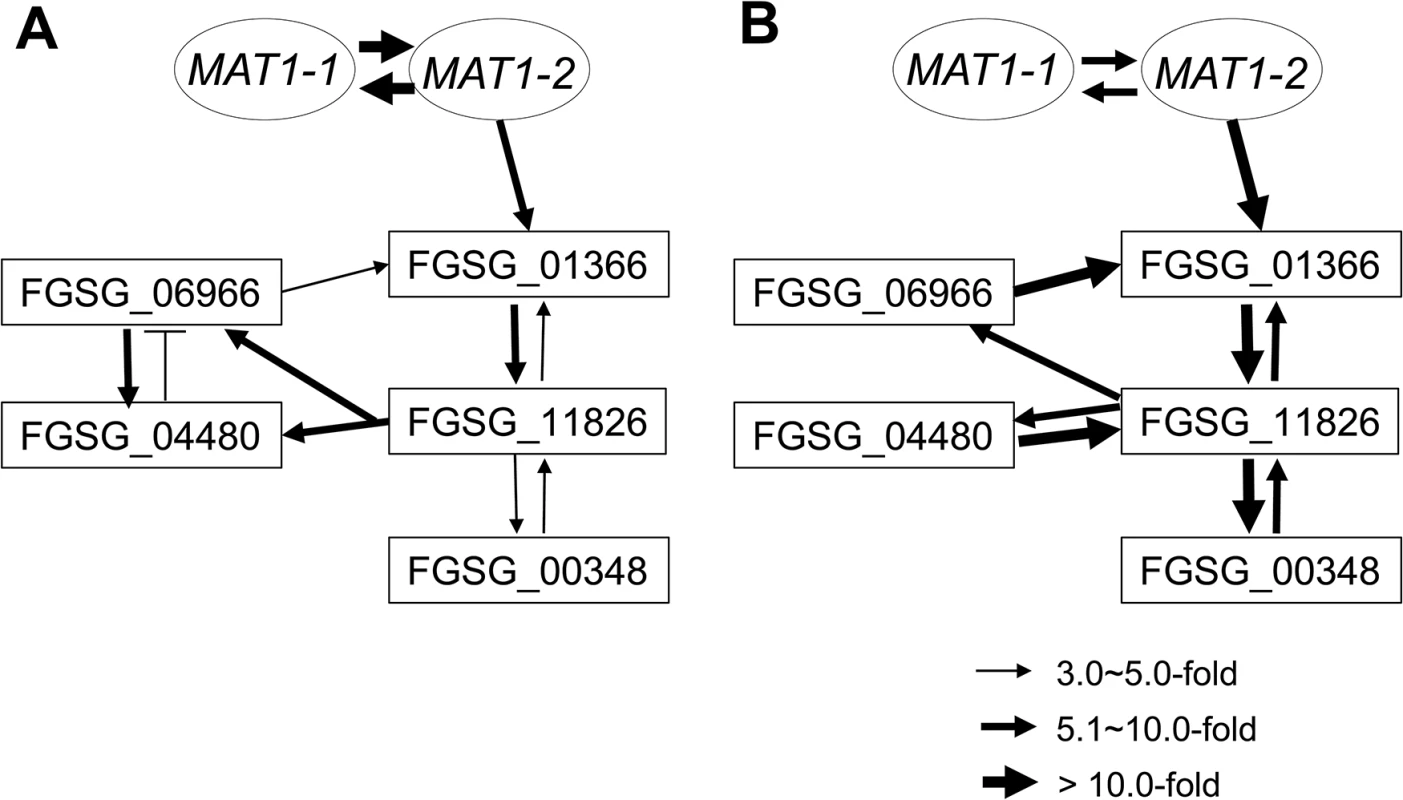

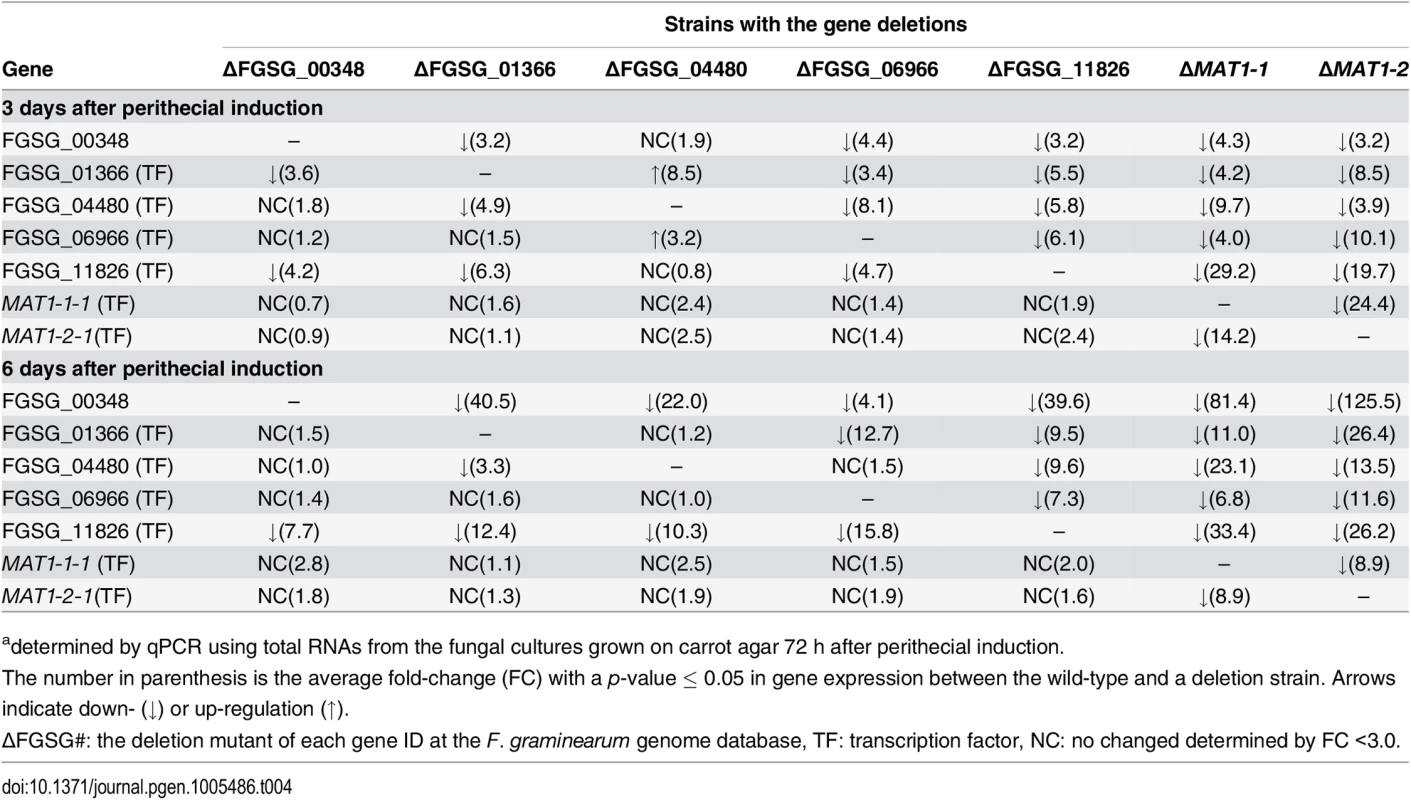

To assess the possible regulatory relationship among the sexual development-specific MAT downstream regulator genes (four transcription factors and one RNAi regulator), we used qPCR to examine their expression patterns in fungal strains in which each gene was deleted during sexual development (3 and 6 days after perithecial induction) (Table 4). Using a fold-change threshold of 3.0, because most genes were expressed at relatively low levels (based on previous transcriptome data [23]), a map of the regulatory interactions among the genes was constructed, as previously performed [39]. Because the core binding sequence of MAT1-2-1 was found in only FGSG_01366, the transcription factor carrying the HMG-box motif, we assumed that FGSG_01366 is the first putative target of MAT1-2-1 in the network (Fig 8). However, the deletion of FGSG_06966, and FGSG_11826 had a significant effect on the expression of FGSG_01366 and other regulatory genes, suggesting that interregulatory networks operate among these genes. Interestingly FGSG_00348, which encodes an Argonaute-like protein was downregulated in strains in which all four transcription factor genes had been individually deleted, suggesting that it was a downstream target of these genes. In addition, none of the target gene deletions had a significant effect on the transcription of MAT1-1-1 and MAT1-2-1, which confirms that these regulatory genes are downstream of the MAT loci in F. graminearum.

Fig. 8. Regulatory networks among the sexual transcription factors (TFs) and an RNAi regulator (FGSG_00348) under control of the MAT loci during sexual development in F. graminearum.

A map of the regulatory interactions among these genes was constructed based on the gene expression patterns in the fungal strains deleted for each regulator during sexual developmental processes [3- (A) and 6- (B) days after perithecial induction on carrot agar] (Table 4). Tab. 4. Expressiona of sexual-specific MAT-target regulator genes in the F. graminearum strains with the corresponding gene deletions.

adetermined by qPCR using total RNAs from the fungal cultures grown on carrot agar 72 h after perithecial induction. Discussion

Identification of DEGs under control of MAT loci

The most significant achievement in this study is that it provided a comprehensive investigation of the putative target genes of the MAT loci during sexual development in self-fertile F. graminearum. Genome-wide transcriptional profiling in various MAT genetic backgrounds, and subsequent in-depth and high-throughput analyses allowed us to explore the regulatory networks and function of MAT-target genes during the early sexual developmental process when the major regulators (MAT1-1-1, MAT1-2-1) of each MAT locus are expressed at their peak levels [14]. Similar to other filamentous ascomycetes, F. graminearum undergoes various cellular processes during each stage of sexual development including mating, cell fusion, nuclear division, fusion, meiosis, ascus/ascospore development, and perithecium maturation. These aspects of sexual development could include pheromone-mediated membrane function, signal transduction, cytoskeleton dynamics, secretory pathways, cell cycle, cell adhesion, apoptosis, and differentiation [40].

The GO terms associated with genes that are differentially expressed in strains carrying a single MAT gene or no MAT gene were significantly enriched for terms related to sexual development processes. In particular, the terms of metabolism including cell wall organization, developmental processes involved in reproduction, and the cellular response to chemical stimulus were enriched among the DDN - and UUN - type DEGs, which are the most frequent groups. Similarly, those described above as well as related to signaling, cellular homeostasis, and cell cycle were enriched among the DEGs that were found in only ΔMAT1-1 or ΔMAT1-2 (DNN-, UNN-, NDN-, and NUN-types).

Unlike the DEGs described above, those from the MAT-null strain (mostly DDD-type) were orthologous to the genes associated with the GO terms that were more specific to sexual development (S3 Table). These genes, most of which were also MAT loci-specific, play important roles in various stages of sexual development ranging from mating to fruiting body formation, which was further confirmed using high-throughput gene deletions. The high frequency of genes specific to sexual development (86.5%; 33 of 38 according to qPCR) among the DEGs suggests that most MAT-target genes are involved in sexual development. A comparison with the study by Hallen et al. [22] identified 169 additional DEGs that were specifically induced during sexual development, which further supports the transcriptional specificity of MAT-target genes.

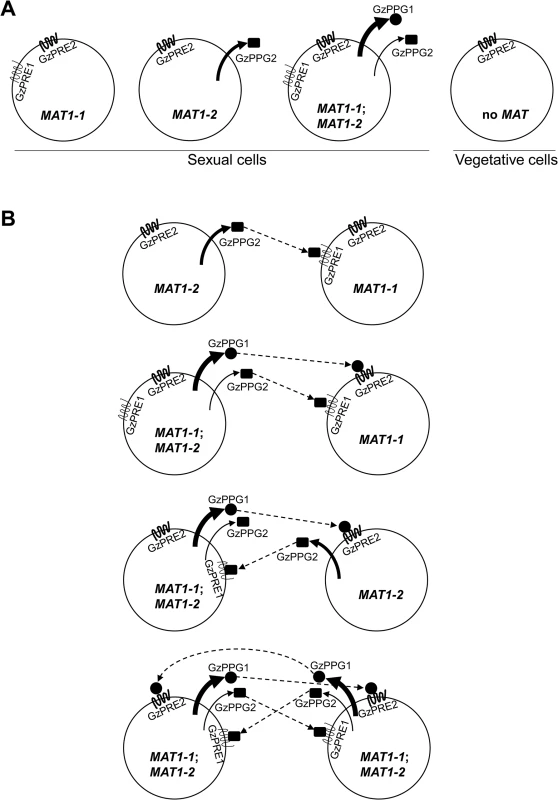

The MAT loci regulate the pheromone/receptor system

It is unclear if or how mating identity is maintained by the MAT-specific pheromone/receptor system in homothallic F. graminearum, although it was suggested that the single (opposite) MAT-mediated intercellular recognition might occur by differential expression of both MAT loci (S10 Fig) [41]. However, in the current study, qPCR of various MAT-deletion strains suggested MAT1-2-locus-specific GzPPG2 expression and MAT1-1-locus-specific GzPRE1 expression (Fig 9). In the homothallic S. macrospora, the pheromone genes ppg1 and ppg2 were downregulated in the ΔSmtA-1 (ΔMAT1-1-1) strain, whereas only ppg2 was downregulated in the ΔSmta-1 strain (ΔMAT1-2-1) [15]. However, it is unknown if the expression pattern of ppg in S. macrospora is MAT-specific, because no studies have been performed in strains lacking the MAT loci. Despite the dispensability of pheromones and their receptors for the formation of fertile perithecia in F. graminearum [30], the qPCR results in the current study predict a role for this system during sexual developmental processes (e.g., pheromone-mediated fertilization or inter-nuclear recognition) in F. graminearum (Fig 9).

Fig. 9. Diagrams for the expression of pheromone precursors and their cognate receptors in the F. graminearum Z3643 strain and its MAT-deletion strains used in this study (A), and for all of the possible interactions between the fungal cells or nuclei for mating in F. graminearum (B).

These diagrams were constructed based on the differential MAT-locus expression in various MAT-deletion strains determined by qPCR (Table 1). The MAT genotypes in the F. graminearum strains are indicated in a circle depicting a fungal cell. MAT1-1;MAT1-2, a self-fertile F. graminearum wild-type (WT) strain carrying both MAT1-1 and MAT1-2 loci; MAT1-1, a self-sterile strain lacking the MAT1-2 locus; MAT1-2, a self-sterile strain lacking MAT1-1; no MAT, a WT strain not expressing both MAT loci. Sexual cells, fungal cells grown under the sexual condition, where MAT gene expression is specifically induced. Vegetative cells: fungal cells during the vegetative growth stage, where no MAT expression occurred. The possible interactions between pheromone precursors and their cognate receptors are indicated by dashed arrows. Once perithecia formation has been induced, WT cells, which carry and express both MAT1-1;MAT1-2 [14], are capable of producing two pheromone precursors (GzPPG1, GzPPG2) and their cognate receptors (GzPRE1, GzPRE2). However, during the vegetative growth stage, WT cells carrying but not expressing both MAT loci [14], which are comparable to MAT-null cells during the sexual stage, produced no pheromones or receptors, except for GzPRE2. (Table 1, Fig 9A). Cells carrying only the MAT1-1 locus (the ΔMAT1-2 strain in this study), which could be present among WT cells as well by differential expression of MAT loci (S10 Fig), if occurs, produce only two pheromone receptors (GzPRE1 and GzPRE2). In contrast, those cells carrying only the MAT1-2 locus can produce the pheromone GzPPG2 as well as the receptor GzPRE2 (Fig 9A). If the exclusive expression of one MAT locus occurs within the parental cells (e.g., the conidia as the male element and the ascogonium as the female element) [40], we could hypothesize that an interaction between two cells is required for fertilization: a cell with only MAT1-1 (designated MAT1-1) with one with MAT1-2 (MAT1-2), MAT1-1 with a WT cell (MAT1-1;MAT1-2), and MAT1-2 with MAT1-1;MAT1-2 (Fig 9B). In the first case, which usually occurs in heterothallic species, the interaction between the GzPPG2 pheromone released from MAT1-2 and its cognate receptor GzPRE1 in MAT1-1 might lead to the fertilization. In the other two cases, the interactions between GzPPG1/GzPRE2 and GzPPG2/GzPRE1 would lead to fertilization. Since GzPPG1 is expressed in the germinating conidia of F. graminearum [42], it is possible that the MAT1-2 and WT strains could act as the male parent in the fertilization model (Fig 9B). The possible fertilization in a heterothallic manner, as proposed in the first combination (MAT1-1 vs. MAT1-2), was previously demonstrated by outcrosses between the ΔMAT1-1;MAT1-2 and MAT1-1;ΔMAT1-2 strains of F. graminearum, which produced fertile perithecia. However, their numbers and fertility were much lower than in the WT strain [11]. A recent study showed that outcrossing ΔMAT1-1;MAT1-2 as the male parent with MAT1-1;ΔMAT1-2 as the female produced partially normal perithecia, whereas an outcross with the reverse parental roles (i.e., ΔMAT1-1;MAT1-2 female × MAT1-1;ΔMAT1-2 male) produced only small, sterile perithecia [13]. The reduced fertility of perithecia in these outcrosses could be attributed to the low level of expression of GzPRE1 in MAT1-1 strain. The failure in the latter outcross could be ascribed to the lack of (or poor) ability of the MAT1-1 strain to produce pheromones as the male parent. The other two combinations for fertilization (Fig 9B) could also yield a successful outcross between WT (male) and either the ΔMAT1-1;MAT1-2 or MAT1-1;ΔMAT1-2 strain (female), as described previously [11]. The retained sexual ability of the F. graminearum strain lacking all of the pheromone and receptor genes suggests that F. graminearum might mate randomly. In addition, the current results reveal the possibility that pheromone-mediated fertilization and/or internucleus recognition occur after random mating in F. graminearum.

The similar effect of ΔMAT1-2 and ΔMAT1-1;ΔMAT1-2 on the expression of two pheromone genes (i.e., downregulation of both GzPPG1 and GzPPG2) could be attributed to the downregulation of MAT1-1 genes in the ΔMAT1-2 strain. However, the effect of ΔMAT1-1 on the expression of GzPPG2 (i.e., upregulation) was opposite that of ΔMAT1-2 or ΔMAT1-1;ΔMAT1-2, suggesting that the effect of ΔMAT1-1 on the expression of MAT1-2 might not be as great as the effect of ΔMAT1-2 on MAT1-1 expression.

Large-scale functional analysis of the selected DEGs

The phenotypic characterization of transgenic strains lacking the selected DEGs provides clear evidence for their functional requirement and specificity for sexual development, as well as the potential stage of their roles during sexual development. Among the 25 genes that were specific to sexual development, 14 (56%) affected the perithecium initial or protoperithecium formation, because the gene deletion strains produced barren protoperithecium (that did not develop further into fertile perithecium), or no perithecium initials (Table 2). This strongly suggests that the MAT loci regulate the genes that are necessary for the cellular events involved in the developmental stages that occur before nuclear fusion and/or meiosis that may subsequently facilitate the formation of mature perithecium and asci/ascospores (S10 Fig). Based on sequence homology, the cellular functions of these sexual-specific genes could be proposed as follows. Two G-protein coupled receptors (the pheromone receptor GzPRE2 and FGSG_05239) might be involved in mating and subsequent signal transduction. Ten TFs, including four MAT genes, might regulate many downstream genes that are necessary for protoperithecium formation. An additional two TFs (FGSG_06228, FGSG_03597), which encode a regulator of G-protein signaling (RGS) protein domain, were upregulated by MAT deletions (UNN - and UUN-type, respectively). Both genes had relatively high sequence similarity to the RGS gene in Aspergillus nidulans, designated FlbA (with 61% and 43% amino acid identities, respectively), which is required for the control of mycelial proliferation and asexual sporulation [43]. FGSG_03597 is also downregulated in OM2. These expression patterns suggest that the MAT1-1 locus might suppress the RGS genes during early sexual development to block the signal transduction pathways required for asexual sporulation.

The suppression of asexual sporulation throughout sexual development has been demonstrated in F. graminearum; conidiation in the self-sterile ΔFgVelB strain was derepressed even during perithecial formation [28]. It is likely that at least one (FGSG_06228) of these genes is the functional homolog of A. nidulans FlbA because the targeted deletion of FGSG_06228 had a significant effect (i.e. an ~11-fold reduction) on conidiation in F. graminearum Z3643, which was different from the phenotypic changes in the Z3639 genetic background [24]. In addition, ΔFGSG_06228 exhibited pleiotropic changes in other traits such as perithecium formation, virulence, and mycotoxin production (S11 Table). Importantly, this study is the first to show inactivation of the FlbA-like gene by the MAT loci during sexual development in filamentous ascomycetes, although the regulatory networks for conidiation in which FlbA plays an important role have been studied in Aspergillus [44]. Since the MAT genes were downregulated in the ΔFgVelB strain, it is possible that FgVelB, a component of the FgVeA complex, controls asexual sporulation by activating the MAT loci. Consistent with this notion, FgVelB controls the expression of MAT genes in F. graminearum [28].

FGSG_07368, a TF that represses ZEA biosynthesis [24], is involved in both ZEA production and perithecium formation because its deletion strain produced ~three-fold higher amounts of ZEA, but formed lower numbers of fertile perithecia compared to WT. This gene is downregulated in the OM2 strain, suggesting that the MAT1-2-1 protein represses ZEA biosynthesis during the perithecia induction stage by suppressing the expression of FGSG_07368. Because the negative effect of ZEA overproduction on sexual development was confirmed in F. graminearum [45], this MAT-induced regulation pattern suggests that the MAT loci acts as a master regulator to both activate and repress the expression of many genes during sexual development.

Seven genes (FGSG_08320, 13708, 06059, 07578, 07869, 03673, 09182) encode enzymes that might participate in the metabolic pathways that are required for protoperithecium formation. In particular, FGSG_09182 (PKS3) and FGSG_08320 are required for perithecial pigment [46] and an unidentified secondary metabolite, respectively. Four genes (FGSG_03916, 10742, 05246, 01862) might be involved in various cellular events such as cell adhesion (FGSG_03916), cellular fusion (FGSG_10742), paraphyses senescence (FGSG_05246), and cytoskeletal organization (FGSG_01862). FGSG_13162, which encodes a protein that controls the histone promoter, might be involved in chromatin silencing and could be required for the regulation of gene expression during protoperithecium formation. Sexual-specific genes are more required for the early stage of sexual development (e.g., the initial perithecium formation) than for postfertilization or post-meiotic events. This suggests that the MAT genes, particularly MAT1-1-1 and MAT1-2-1, whose transcripts accumulate at the highest levels during the early stage [13, 14], control the genes that are involved in this stage more than those that regulate the later stages (e.g., nuclear fusion, meiosis, ascus maturation). However, it could also be attributed to the time point (48 h after perithecium induction) at which total RNA samples were extracted for microarray analysis. Nevertheless, the possibility that the MAT loci regulate both the early and late stages of sexual development is supported by the phenotypes of transgenic strains that lack each of three remaining genes (FGSG_00348, 00532, 02052). Specifically, these strains could produce mature perithecium, although the number of perithecia produced was lower (FGSG_00348) or higher (FGSG_00532) than WT. This suggests that the MAT genes also control the expression of the genes that are required for post-fertilization processes.

In particular, the deduced product of FGSG_00348, designated FgSMS-2, contains the PAZ - and Piwi domains that are also found in SMS-2 from N. crassa and AGO2 (Argonaute) from D. melanogaster. These proteins play an important role in the RNA silencing known as meiotic silencing by unpaired DNA (MSUD) and siRNA-directed RNA interference, respectively [32, 47]; they are the active part of the RNA-induced silencing complex and required for cleaving the target mRNA. The formation of asci carrying an incomplete set of ascospores or abnormally shaped ascospores in the ΔFgSMS-2 strain suggests that the MAT loci regulate the meiotic events that lead to asci/ascospore development by activating the expression of FgSMS-2, which might control the RNAi pathway in F. graminearum. Another SMS-2 ortholog (FGSG_0872) is present in the F. graminearum genome, which is similar to the N. crassa gene Qde-2, which regulates another RNA silencing pathway (quelling) during vegetative growth. However, the lack of transcriptional control of FGSG_0872 by MAT and the phenotypic changes caused by gene deletion suggest that FgSMS-2 is the only Argonaute-like gene that controls meiosis and the subsequent developmental pathways in F. graminearum. The upregulation of three DEGs caused by ΔFgSMS-2 during perithecial formation (S6 Fig) suggests that FgSMS-2 is involved in the degradation of the mRNA of these genes in F. graminearum, which is comparable to the role of Argonaute proteins. However, further investigations are necessary for confirmation, such as exploring and characterizing small RNAs.

Interestingly, 17 of the 21 sexual-specific genes (excluding 4 MAT genes) were downregulated in the MAT-null strain as well as ΔMAT1-1 and ΔMAT1-2. The four remaining genes included FGSG_03916, which is repressed during sexual development, and FGSG_02655 (GzPRE2) and FGSG_00404, which are both differentially regulated only in OM2. These data suggest that all of the genes with sexual-specific functions are regulated by both the MAT1-1 and MAT1-2 loci. This also indicates that the presence of both MAT1-1 and MAT1-2 proteins within a separate or common nucleus is necessary for controlling most stages of sexual development, from ascogonium formation to perithecium maturation (S10 Fig). In addition, the high frequency (72%) of enrichment of XXD-type DEGs at a later stage (96 h after perithecial induction), which is dramatically different from the XXN-type DEGs enriched at the earlier stages (Table 3), strongly suggests that both MAT1-1 and MAT1-2 are required to control stages of development later than fertilization. However, the functional assignment of these DEGs into particular growth stages is based on only developmental time course gene expression, and awaits further confirmation.

The regulation of sexual development by MAT in F. graminearum

Taken together, the results of the current and previous studies provide insights toward a comprehensive understanding of the MAT-mediated regulatory pathways that control sexual development in F. graminearum (Fig 10). The environmental cues for sexual development elucidated to date in F. graminearum are light, nutrient conditions (probably nitrogen starvation), and mycelial autophagy [40]. In contrast to A. nidulans, F. graminearum only produces fertile perithecia on carrot agar in the presence of light. The molecular characterization of F. graminearum orthologs (FgWC-1 [FGSG_07941] and FgWC-2 [FGSG_00710]) of the photoreceptors encoding wc-1 and wc-2 in N. crassa revealed that these two genes repress the expression of MAT genes during the sexual development (within 3−5 days of perithecial induction) [48]. Similarly, FgLaeA, a component of the FgVeA complex that is involved in chromatin remodeling, is also likely to repress MAT gene expression, because the MAT genes were upregulated in the ΔFgLaeA strain [49]. However, other members of the FgVeA complex, FgVeA and FgVelB, activate MAT gene expression because the MAT genes were downregulated in the ΔFgVelB strain, and the ΔFgVeA strain was self-sterile [28]. Taken together, it is possible to speculate that the expression of the MAT genes could be activated or repressed by chromatin remodeling via FgWC-1/FgWC-2 and FgVeA complexes. However, this speculation awaits further investigation. The downregulation of MAT genes in the ΔGzGPA1 strain [33] suggests that they can also be positively regulated by a G-protein-mediated signal transduction pathway, which is probably induced via nutrient sensing. The deletion of most of the genes in the G-protein signaling pathway, including the MAP kinase and cAMP cascades, caused dramatic changes in several traits, including sexual development [50–54]. This suggests that the MAT loci might be under the control of these signaling pathways. In contrast, most of the genes involved in these signaling pathways (S14 Table) were not differentially regulated in the MAT-deletion strains examined in this study. This suggests that MAT does not regulate these pathways.

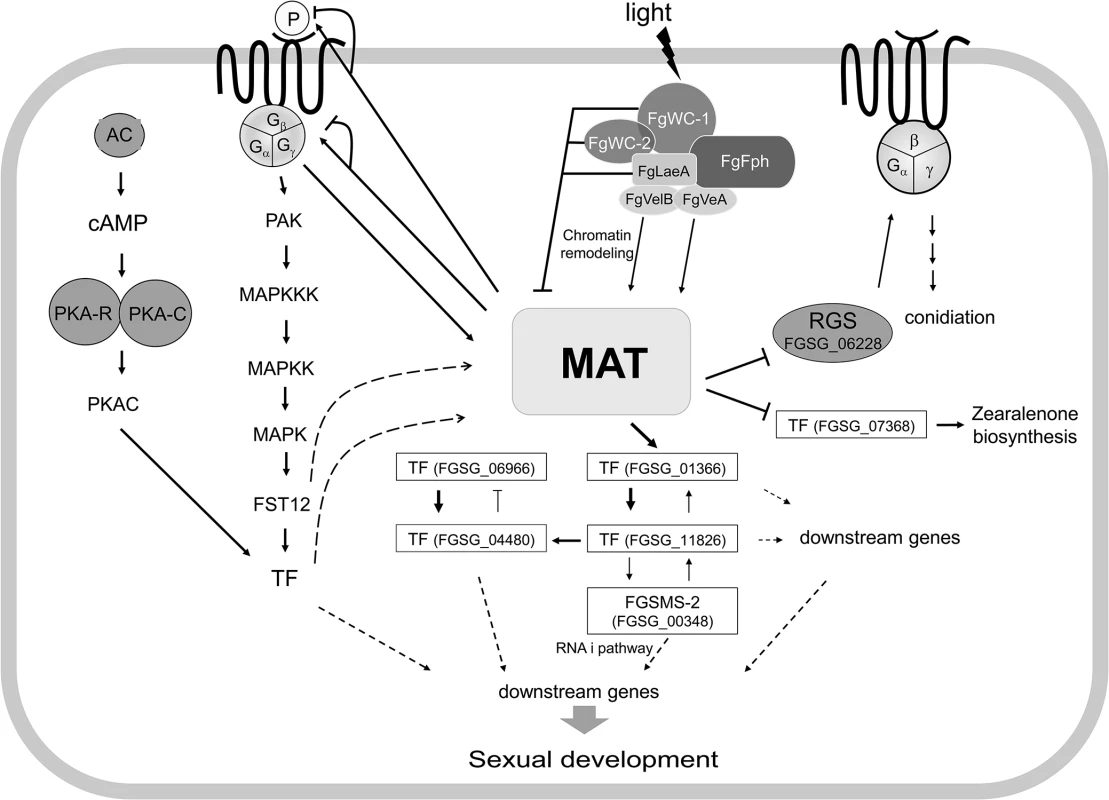

Fig. 10. Schematic diagram of possible regulatory pathways of MAT-mediated sexual development in F. graminearum.

The expression of both MAT loci are regulated by several environmental cues (e.g., light), probably via chromatin remodeling by the FgVeA complex and/or G-protein signaling pathways, and control the expression of putative target genes via regulatory cascades and/or networks involving several downstream transcription factors (TFs) and an RNAi regulator (FgSMS-2). Abbreviations: MAT, mating-type proteins encoded by both MAT1-1 and MAT1-2 loci; AC, adenyl cyclase; PKA-R, protein kinase A regulatory subunit; PKA-C, protein kinase A catalytic subunit; PAK, protein kinase; FST12, an F. graminearum ortholgoue of the yeast STE12; RGS, Regulator of G-protein signaling; P, pheromones. Solid lines with triangular and flattened arrowheads represent gene activation and repression, respectively. The dashed arrows indicate possible regulatory directions, not determined by qPCR. Once activated under perithecial induction conditions [14], MAT genes control the expression of the pheromone/receptor system in a MAT-specific manner (particularly for GzPPG2 and its cognate receptor GzPRE1), suggesting that MAT plays a role in pheromone-mediated fertilization. However, it is unclear if the maintenance of cell identity for mating, which might be mediated by the MAT-specific pheromone/receptor system and/or by a single MAT locus, occurs in F. graminearum, although the differential expression of each MAT locus within a single nucleus has been suggested in this regard. It is still possible that the pheromone/receptor system plays an important role in the stages after fertilization, such as during inter-nuclear recognition.

Based on the genome and promoter microarray results in the current study, it is possible that the regulation of sexual development under the control of the MAT loci might involve cascades or networks that are downstream of TFs. Focusing on the TFs that are specific to sexual development at both the gene expression and functional levels allows a model of regulation of these TFs by the MAT loci to be proposed (Fig 10). Although inter-regulatory networks between these TFs have also been proposed, it is possible that these major TFs control the expression of the genes that are involved in various molecular processes related to sexual development, conidiation, and zearalenone production. In this regulatory circuit, the HMG-box motif containing TF FGSG_01366 is the main downstream regulator of the MAT loci. Interestingly, FGSG_01366 is an ortholog of PaHMG5 in P. anserina, which plays a crucial role in a network containing several HMG-box factors that regulate mating-type genes and their target genes [39]. However, the regulatory roles of these HMG-box TFs for sexual development differ between the two species. FGSG_01366 is a downstream target of the MAT loci in F. graminearum, whereas PaHMG5 is an upstream regulator of mating-type genes (FMR1 and FPR1, which are comparable to MAT1-1-1 and MAT1-2-1, respectively) and the pheromone/receptor system [39]. The expression of the F. graminearum ortholog (FGSG_05151) of the other HMG box gene (PaHMG8), a downstream target of PaHMG5, in P. anserina was also downregulated in the MAT-null background (NND-type). This suggests that FGSG_05151 is a member of the regulatory circuit of TFs that are under the control of the MAT loci (Fig 10), although the gene deletion phenotype was not as dramatic as that for FGSG_01366 (Table 2). The other regulatory mechanism under the control of the MAT loci might be the RNAi pathway involved in meiosis and/or ascus development. Although RNAi-mediated MSUD was not demonstrated in F. graminearum, the functional requirement of the Argonaute-like protein FgSMS-2 for ascus maturation and ascospore morphology and upregulation of several DEGs by ΔFgSMS-2 suggests that RNAi may have a regulatory role during meiosis in F. graminearum.

The time course expression pattern and deletion of selected DEGs suggest that major MAT genes (MAT1-1-1, MAT1-2-1), which are highly induced at an early stage, regulate the genes involved in the later as well as early stages of sexual development (e.g., meiosis, ascospore formation, discharge). This suggests that MAT loci play crucial roles throughout sexual development in F. graminearum.

In summary, both MAT loci are activated by several environmental cues via chromatin remodeling and/or signaling pathways, and then control the expression of at least 1,245 target genes during the early stage of sexual development via regulatory cascades and/or networks involving several downstream TFs and RNAi. The regulatory effects of the MAT loci on these target genes could be directly achieved by the binding of MAT1-2-1 protein to core sequences within the promoter regions of some target genes, or indirectly via downstream TFs.

Materials and Methods

Fungal strains and culture conditions

The F. graminearum WT strains PH-1 and Z3643 [55], which belong to lineage seven of the F. graminearum species complex [5, 17], are self-fertile. T43ΔM1-3 [25], T43ΔM2-2 [17], and T43ΔDM1M2 (S1 Fig) are self-sterile transgenic mutants derived from Z3643, and lack MAT1-1, MAT1-2, and both MAT1-1 and MAT1-2 loci, respectively. The ΔMAT1-1-1, ΔMAT1-1-2, and ΔMAT1-1-3 strains were previously generated by deleting the MAT1-1-1, MAT1-1-2, and MAT1-1-3 transcripts at the MAT1-1 locus of Z3643, respectively; they are all self-sterile [14]. OM2 (S2 Fig) is a MAT1-2-1-overexpressing strain that was generated by insertion of MAT1-2-1 into the T43ΔM2-2 strain under the control of the F. fujikuroi EF1A promoter. The WT and transgenic strains were stored in 20% glycerol at –70°C. Sexual development was induced on carrot agar, as previously described [11, 56]. For genomic DNA extraction, each strain was grown in 50 mL CM [56] at 25°C for 72 h on a rotary shaker (150 rpm). Conidiation was induced in CMC liquid medium [57].

Nucleic acid manipulations, primers, and qPCR

Fungal genomic DNA was prepared as previously described [56, 58], and total RNA was extracted from mycelia and/or protoperithecia that had formed on carrot agar using an Easy-Spin Total RNA Extraction kit (Intron Biotech, Seongnam, Korea) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All of the PCR primers used in this study (S15 Table) were synthesized by Bioneer Corporation (Chungwon, Korea). DNA gel blots were prepared [59] and hybridized using biotinylated DNA probes that were prepared using the BioPrime DNA labeling system (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), and were developed using the BrightStar BioDetect Kit (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA). Other general procedures for nucleic acid manipulations were performed as previously described [59]. qPCR was performed using SYBR Green Super Mix (Bio-Rad) with first-strand cDNA synthesized from total RNA [33, 60]. The amplification efficiency of all genes was determined as previously described [60]. Gene expression was measured in three biological replicates from each time point. EF1A (FGSG_08811) was used as an endogenous control for data normalization [60].

Luciferase assays and virulence tests

Fungal strains were grown in 20 mL agmatine-amended liquid medium [61] for trichothecene production and SG liquid medium [62] for zearalenone production, as previously described. Luciferase activity was then measured in cell lysates from the strains using GloMax 96 Microplate Luminometer (Promega) as previously described [63]. The virulence of the fungal strains was determined on wheat heads as previously described [49].

Microarrays

Total RNAs were isolated from carrot agar cultures of the F. graminearum Z3643 WT strain carrying both MAT1-1 and MAT1-2, three MAT-deletion strains (ΔMAT1-1 [carrying only MAT1-2], ΔMAT1-2 [carrying only MAT1-1], and ΔMAT1-1;ΔMAT1-2), and the OM2 strain, which had been grown for 2 days after sexual induction. Double strand cDNAs were synthesized as previously described [33]. Microarray analysis was conducted at GreenGene Biotech (Yongin, Korea) using the F. graminearum microarray that was manufactured at NimbleGen (Madison, WI, USA), as previously described [33]. This array includes 13,382 transcripts from F. graminearum sequencing assembly three. Experiments were repeated three times with total RNA samples that were independently prepared. Microarrays were scanned using Genepix 4000 B (Axon Instruments, Toronto, Canada), and the signals were analyzed with Nimblescan 2.5 (NimbleGen).

The data were normalized and processed with cubic spline normalization using quantiles to adjust for signal variation among chips [64]. Probe-level summarization using Robust Multi-Chip Analysis (RMA) with a median polish algorithm implemented in NimbleScan was used to produce call files. Multiple analyses were performed using the limma package in an R computing environment [65]. Genes with P ≤ 0.05 (significant) were collected and selected further for genes with expression > 1 or < −1 in at least one MAT genetic background compared to another background such as WT (MAT1-1;MAT1-2), or MAT-null (ΔMAT1-1;ΔMAT1-2). The entire dataset from the microarrays was deposited in the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo) under the accession number GSE58543.

GO analysis

The DEGs identified in this study were examined for significant enrichment of functional categorization using GO analysis [66]. The GO term enrichments were calculated with GOMINER [66, 67] (http://www.geneontology.org/, http://discover.nci.nih.gov/gominer/). The 11,603 genes were matched to A. nidulans FGSC A4 sequencing assembly (Aspergillus Genome Database; http://www.aspergillusgenome.org/) with score 30 and up by BlastP analysis, and were used as total gene set in gominer for GOMINER analysis. Gominer first categorize each gene according to their GO terms and mode of gene expressions either down - or up - regulation. It calculates p-values with the one-sided Fisher exact test for the number of categorized GO terms in the total. The GO terms with p-value less than 0.05 were considered significantly enriched among the DEGs, and used in further analysis.

Targeted deletions of the selected DEGs

DNA constructs to delete individual DEGs from the genomes of F. graminearum Z3643 or PH-1 were created using a split marker recombination procedure, as previously described [68]. Generally, the 5′ and 3′ flanking regions of the target gene, which were amplified by PCR using the primers listed in S15 Table, were mixed with the gen or hygB cassettes, which were amplified from pII99 and pBCATPH using the primer pairs Gen-for/Gen-rev and Hyg-for/Hyg-rev, respectively. The final split markers were amplified from the mixture using the new nested primer sets (S15 Table). The amplified products were added into WT F. graminearum protoplasts for transformation, as previously described [14, 49]. Gene deletion was confirmed using either DNA gel blot hybridization or PCR (S11 Fig).

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. McMullen M, Jones R, Gallenberg D. Scab of wheat and barley: a re-emerging disease of devastating impact. Plant Dis. 1997;81 : 1340–8.

2. Starkey DE, Ward TJ, Aoki T, Gale LR, Kistler HC, Geiser DM, et al. Global molecular surveillance reveals novel Fusarium head blight species and trichothecene toxin diversity. Fungal Genet Biol. 2007;44 : 1191–204. 17451976

3. Sarver BA, Ward TJ, Gale LR, Broz K, Kistler HC, Aoki T, et al. Novel Fusarium head blight pathogens from Nepal and Louisiana revealed by multilocus genealogical concordance. Fungal Genet Biol. 2011;48 : 1096–107. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2011.09.002 22004876

4. O'Donnell K, Ward TJ, Aberra D, Kistler HC, Aoki T, Orwig N, et al. Multilocus genotyping and molecular phylogenetics resolve a novel head blight pathogen within the Fusarium graminearum species complex from Ethiopia. Fungal Genet Biol. 2008;45 : 1514–22. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2008.09.002 18824240

5. O'Donnell K, Kistler HC, Tacke BK, Casper HH. Gene genealogies reveal global phylogeographic structure and reproductive isolation among lineages of Fusarium graminearum, the fungus causing wheat scab. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97 : 7905–10. 10869425

6. O'Donnell K, Ward TJ, Geiser DM, Corby Kistler H, Aoki T. Genealogical concordance between the mating type locus and seven other nuclear genes supports formal recognition of nine phylogenetically distinct species within the Fusarium graminearum clade. Fungal Genet Biol. 2004;41 : 600–23. 15121083

7. Yli-Mattila T, Gagkaeva T, Ward TJ, Aoki T, Kistler HC, O'Donnell K. A novel Asian clade within the Fusarium graminearum species complex includes a newly discovered cereal head blight pathogen from the Russian Far East. Mycologia. 2009;101 : 841–52. 19927749

8. Trail F, Xu H, Loranger R, Gadoury D. Physiological and environmental aspects of ascospore discharge in Gibberella zeae (anamorph Fusarium graminearum). Mycologia. 2002;94 : 181–9. 21156487

9. Debuchy R, Turgeon BG. Mating-type structure, evolution, and function in Euascomycetes. In: Kues U, Fischer R, editors. The Mycota. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 2006. p. 293–323.

10. Yun SH, Arie T, Kaneko I, Yoder OC, Turgeon BG. Molecular organization of mating type loci in heterothallic, homothallic, and asexual Gibberella/Fusarium species. Fungal Genet Biol. 2000;31 : 7–20. 11118131

11. Lee J, Lee T, Lee YW, Yun SH, Turgeon BG. Shifting fungal reproductive mode by manipulation of mating type genes: obligatory heterothallism of Gibberella zeae. Mol Microbiol. 2003;50 : 145–52. 14507370

12. Desjardins AE, Brown DW, Yun SH, Proctor RH, Lee T, Plattner RD, et al. Deletion and complementation of the mating type (MAT) locus of the wheat head blight pathogen Gibberella zeae. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70 : 2437–44. 15066842

13. Zheng Q, Hou R, Juanyu, Zhang, Ma J, Wu Z, et al. The MAT locus genes play different roles in sexual reproduction and pathogenesis in Fusarium graminearum. PloS one. 2013;8(6): e66980. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066980 23826182

14. Kim HK, Cho EJ, Lee S, Lee YS, Yun SH. Functional analyses of individual mating-type transcripts at MAT loci in Fusarium graminearum and Fusarium asiaticum. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2012;337 : 89–96. doi: 10.1111/1574-6968.12012 22998651

15. Klix V, Nowrousian M, Ringelberg C, Loros JJ, Dunlap JC, Pöggeler S. Functional characterization of MAT1-1-specific mating-type genes in the homothallic ascomycete Sordaria macrospora provides new insights into essential and nonessential sexual regulators. Eukary Cell. 2010;9 : 894–905.

16. Martin SH, Wingfield BD, Wingfield MJ, Steenkamp ET. Structure and evolution of the Fusarium mating type locus: new insights from the Gibberellafujikuroi complex. Fungal Genet Biol. 2011;48 : 731–40. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2011.03.005 21453780

17. Lee SH, Lee S, Choi D, Lee YW, Yun SH. Identification of the down-regulated genes in a mat1-2-deleted strain of Gibberella zeae, using cDNA subtraction and microarray analysis. Fungal Genet Biol. 2006;43 : 295–310. 16504554

18. Keszthelyi A, Jeney A, Kerényi Z, Mendes O, Waalwijk C, Hornok L. Tagging target genes of the MAT1-2-1 transcription factor in Fusarium verticillioides (Gibberella fujikuroi MP-A). Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2007;91 : 373–91. 17124547

19. Pöggeler S, Nowrousian M, Ringelberg C, Loros JJ, Dunlap JC, Kuck U. Microarray and real-time PCR analyses reveal mating type-dependent gene expression in a homothallic fungus. Mol Genet Genom. 2006;275 : 492–503.

20. Bidard F, Ait Benkhali J, Coppin E, Imbeaud S, Grognet P, Delacroix H, et al. Genome-wide gene expression profiling of fertilization competent mycelium in opposite mating types in the heterothallic fungus Podospora anserina. PLoS One. 2011;6(6):e21476. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021476 21738678

21. Becker K, Beer C, Freitag M, Kuck U. Genome-wide identification of target genes of a mating-type alpha-domain transcription factor reveals functions beyond sexual development. Mol Microbiol 2015;96 : 1002–22. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12987 25728030

22. Hallen HE, Huebner M, Shiu SH, Guldener U, Trail F. Gene expression shifts during perithecium development in Gibberella zeae (anamorph Fusarium graminearum), with particular emphasis on ion transport proteins. Fungal Genet Biol. 2007;44 : 1146–56. 17555994

23. Sikhakolli UR, Lopez-Giraldez F, Li N, Common R, Townsend JP, Trail F. Transcriptome analyses during fruiting body formation in Fusarium graminearum and Fusarium verticillioides reflect species life history and ecology. Fungal Genet Biol. 2012;49 : 663–73. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2012.05.009 22705880

24. Son H, Seo YS, Min K, Park AR, Lee J, Jin JM, et al. A phenome-based functional analysis of transcription factors in the cereal head blight fungus, Fusarium graminearum. PLoS Pathogens. 2011;7(10): e1002310. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002310 22028654

25. Lee SH, Kim YK, Yun SH, Lee YW. Identification of differentially expressed proteins in a mat1-2-deleted strain of Gibberella zeae, using a comparative proteomics analysis. Curr Genet. 2008;53 : 175–84. doi: 10.1007/s00294-008-0176-z 18214489

26. Sieber CM, Lee W, Wong P, Munsterkotter M, Mewes HW, Schmeitzl C, et al. The Fusarium graminearum genome reveals more secondary metabolite gene clusters and hints of horizontal gene transfer. PLoS One. 2014;9(10): e110311. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0110311 25333987

27. Bushley KE, Ripoll DR, Turgeon BG. Module evolution and substrate specificity of fungal nonribosomal peptide synthetases involved in siderophore biosynthesis. BMC Evol Biol. 2008;8 : 328. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-8-328 19055762

28. Lee J, Myong K, Kim JE, Kim HK, Yun SH, Lee YW. FgVelB globally regulates sexual reproduction, mycotoxin production and pathogenicity in the cereal pathogen Fusarium graminearum. Microbiology. 2012;158 : 1723–33. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.059188-0 22516221

29. Yu HY, Seo JA, Kim JE, Han KH, Shim WB, Yun SH, et al. Functional analyses of heterotrimeric G protein G alpha and G beta subunits in Gibberella zeae. Microbiology. 2008;154 : 392–401. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2007/012260-0 18227243

30. Kim HK, Lee T, Yun SH. A putative pheromone signaling pathway is dispensable for self-fertility in the homothallic ascomycete Gibberella zeae. Fungal Genet Biol. 2008;45 : 1188–96. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2008.05.008 18567512

31. Carmell MA, Xuan Z, Zhang MQ, Hannon GJ. The Argonaute family: tentacles that reach into RNAi, developmental control, stem cell maintenance, and tumorigenesis. Genes Develop 2002;16 : 2733–42. 12414724

32. Lee DW, Pratt RJ, McLaughlin M, Aramayo R. An argonaute-like protein is required for meiotic silencing. Genetics 2003;164 : 821–8. 12807800

33. Lee J, Park C, Kim JC, Kim JE, Lee YW. Identification and functional characterization of genes involved in the sexual reproduction of the ascomycete fungus Gibberella zeae. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 2010;401 : 48–52. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.09.005 20836989

34. Kim MJ, Lee TH, Pahk YM, Kim YH, Park HM, Choi YD, et al. Quadruple 9-mer-based protein binding microarray with DsRed fusion protein. BMC Mol Biol. 2009;10 : 91. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-10-91 19761621

35. Berger MF, Philippakis AA, Qureshi AM, He FS, Estep PW 3rd, Bulyk ML. Compact, universal DNA microarrays to comprehensively determine transcription-factor binding site specificities. Nature Biotech. 2006;24 : 1429–35.

36. Denny P, Swift S, Connor F, Ashworth A. An SRY-related gene expressed during spermatogenesis in the mouse encodes a sequence-specific DNA-binding protein. EMBO J 1992;11 : 3705–12. 1396566

37. Harley VR, Lovell-Badge R, Goodfellow PN. Definition of a consensus DNA binding site for SRY. Nucleic Acids Res 1994;22 : 1500–1. 8190643

38. Kanai Y, Kanai-Azuma M, Noce T, Saido TC, Shiroishi T, Hayashi Y, et al. Identification of two Sox17 messenger RNA isoforms, with and without the high mobility group box region, and their differential expression in mouse spermatogenesis. J Cell Biol 1996;133 : 667–81. 8636240

39. Ait Benkhali J, Coppin E, Brun S, Peraza-Reyes L, Martin T, Dixelius C, et al. A network of HMG-box transcription factors regulates sexual cycle in the fungus Podospora anserina. PLoS Genet. 2013;9: e1003642. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003642 23935511