-

Články

- Časopisy

- Kurzy

- Témy

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Sigma Factor SigB Is Crucial to Mediate Adaptation during Chronic Infections

Staphylococcus aureus is a frequent pathogen of severe invasive infections that can develop into chronicity and become extremely difficult to eradicate. Chronic infections have been highly associated with altered bacterial phenotypes, i.e., the small colony variants (SCVs) that dynamically appear after bacterial host cell invasion and are highly adapted for intracellular long-term persistence. In this study, we analyzed the underlying mechanisms of the bacterial switching and adaptation process by investigating the functions of the global S. aureus regulators agr, sarA and SigB. We demonstrate that a tight crosstalk between these factors supports the bacteria at any stage of the infection and that SigB is the crucial factor for bacterial adaptation during long-term persistence. In the acute phase, the bacteria require active agr and sarA systems to induce inflammation and cytotoxicity, and to establish an infection at high bacterial numbers. In the chronic stage of infection, SigB downregulates the aggressive bacterial phenotype and mediates the formation of dynamic SCV-phenotypes. Consequently, we describe SigB as a crucial factor for bacterial adaptation and persistence, which represents a possible target for therapeutic interventions against chronic infections.

Published in the journal: Sigma Factor SigB Is Crucial to Mediate Adaptation during Chronic Infections. PLoS Pathog 11(4): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1004870

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1004870Summary

Staphylococcus aureus is a frequent pathogen of severe invasive infections that can develop into chronicity and become extremely difficult to eradicate. Chronic infections have been highly associated with altered bacterial phenotypes, i.e., the small colony variants (SCVs) that dynamically appear after bacterial host cell invasion and are highly adapted for intracellular long-term persistence. In this study, we analyzed the underlying mechanisms of the bacterial switching and adaptation process by investigating the functions of the global S. aureus regulators agr, sarA and SigB. We demonstrate that a tight crosstalk between these factors supports the bacteria at any stage of the infection and that SigB is the crucial factor for bacterial adaptation during long-term persistence. In the acute phase, the bacteria require active agr and sarA systems to induce inflammation and cytotoxicity, and to establish an infection at high bacterial numbers. In the chronic stage of infection, SigB downregulates the aggressive bacterial phenotype and mediates the formation of dynamic SCV-phenotypes. Consequently, we describe SigB as a crucial factor for bacterial adaptation and persistence, which represents a possible target for therapeutic interventions against chronic infections.

Introduction

S. aureus is a major human pathogen that can infect almost every organ in the body and cause destructive infections [1]. Besides tissue damage the ability to develop persisting and therapy-refractory infections poses a major problem in clinical practice, such as endovascular and bone infections [2,3]. Chronic infections require prolonged antimicrobial treatments and can have a dramatic impact on the patients`quality of life, as they often afford repeated surgical interventions with the risk of amputation or loss of function [2,4].

To induce an infection S. aureus expresses a multitude of virulence factors, including surface proteins and secreted components, like toxins and peptides [1]. Toxins and other secreted factors are mainly directed against invading immune cells, but can also cause tissue damage that enables the bacteria to enter deep tissue structures [5,6]. Yet, S. aureus is not only an extracellular pathogen, but can also invade a wide variety of mammalian cells, such as osteoblasts, epithelial - and endothelial cells [7–9]. All cells discussed in the literature as “non-professional phagocytes” possess mechanisms that nevertheless permit endocytotic uptake and degradation of microorganisms [10–12]. To evade the intracellular degradation machineries the bacteria have evolved different strategies, such as the killing of host cells or the escape from the lysosomal compartments and silent persistence within the intracellular location [8,13,14]. Only recently, we demonstrated that S. aureus can dynamically switch phenotypes from a highly aggressive and cytotoxic wild-type form to a metabolically inactive phenotype (small colony variants, SCVs) that is able to persist for long time periods within host cells without provoking a response from the host immune system [9]. In their intracellular location the bacteria are most likely very well protected from antimicrobial treatments and the host´s defense system. This is a possible reservoir for chronic and recurrent infections. Yet, the environmental changes encountered by invading bacteria during the passage from an extracellular to the intracellular milieu and during long term persistence within the intracellular shelter most likely cause diverse stress conditions. The adaptation mechanisms involved and how bacteria cope with this stress, are largely unknown, but probably involve global changes in gene expression to promote survival.

It is well known that S. aureus possess a large set of regulatory factors that control the expression of virulence determinants [15–18]. A very important and well-studied system is the accessory gene regulator (agr)-locus with the effector molecule RNA III [19,20]. Many S. aureus derived factors that induce inflammation or cell death are under the control of this system. Important cytotoxic components regulated by the agr-system are the pore-forming α-hemolysin (α-toxin, Hla) and the phenol-soluble modulins (PSMs), which are strong cytotoxic and pro-inflammatory factors in different host cell types [6,21–23]. SarA, which is the major protein encoded by the sar-locus, is believed to contribute to the activation of agr expression [24,25]. This is supported by findings of many S. aureus infection models demonstrating that mutations of either loci result in attenuation of virulence [26–28]. Beyond that, it has been shown that SarA influences the regulation of several virulence factors independently of agr, e.g. expression of adhesins [25,29,30]. The alternative sigma factor B (SigB; σB) modulates the stress response of several Gram-positive bacteria, including S. aureus [31–33]. SigB is responsible for the transcription of genes that can confer resistance to heat, oxidative and antibiotic stresses [16,31,34,35]. The sigB system is linked to the complex S. aureus regulatory network, as it increases sarA expression, but decreases RNA III production [36].

During the infection process the bacteria encounter different stressful conditions that they need to overcome in order to settle and maintain an infection. In the acute infection they have to fight against invading immune cells and destroy tissue cells to enter deep tissue structures, whereas during the chronic phase a major challenge is most likely the hostile intracellular location deprived of nutrients and lysosomal degradation. Consequently, the host-pathogen interaction needs to be very dynamic. Yet, to date no studies have followed the adaptation mechanisms and the impact of regulators during the whole infection process. In this work we focused on the interaction of the global regulatory systems agr, SarA and SigB and we demonstrate a crucial function for SigB in bacterial adaptation mechanisms and the formation of SCV-phenotypes.

Results

Agr and SarA are required for inflammation and cytotoxicity

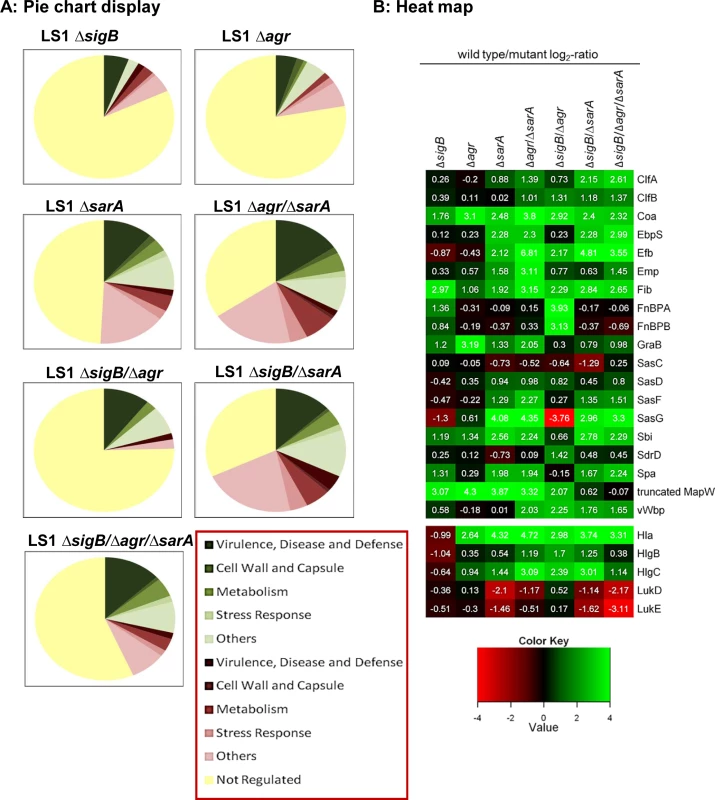

For our study we generated single mutants for the functions of SigB (ΔsigB), agr (Δagr), SarA (ΔsarA) and the complemented mutant for sigB (ΔsigB compl.), three double mutants for SigB, agr, SarA (Δagr/ΔsarA, ΔsigB/Δagr, ΔsigB/ΔsarA) and a triple mutant (ΔsigB/Δagr/ΔsarA) in S. aureus LS1, a strain derived from mouse osteomyelitis [37]. Several mutants were also generated in the rsbU complemented derivative of the laboratory strain 8325–4, SH1000 [33] (Supp. S1 Table). All strains and mutants were characterized by growth curves, which did not reveal any substantial differences between mutants and parent strains (S1 Fig). Yet, differences in hemolysis were present in many mutants, particularly in the agr-, sarA-, double and triple mutants, which exhibited low hemolysis (S1C Fig). Furthermore, the strain LS1 and the corresponding mutants were analyzed by LC-MS/MS mass spectrometry, which was focused onto the culture supernatants to provide an overview on the levels of virulence factors in each strain (Fig 1A and S3 Table). These data show that particularly the sarA-mutant and even more the double and the triple-mutants released a much reduced number of virulence factors associated with disease development compared with the wild-type strain LS1 (reduced levels of virulence factors associated with disease; deep green areas, Fig 1A); in particular different adhesive proteins and toxins were present in reduced levels in culture supernatants (Fig 1B). Yet, for the FnBPs that are important for host cell invasion we detected similar levels compared with the wild-type LS1 in most mutants that can account for the invasive capacity of the strains in host cells (S5 Fig). Most importantly, the sigB-mutant showed only modest alterations in protein levels (Fig 1A), but increased levels of α-toxin that is known as a strong proinflammatory and cytotoxic factor after host cell invasion (hla, Fig 1B). The other listed toxins, e.g. lukD and lukE, are reported as non-hemolytic and only poorly leucotoxic toxins [37].

Fig. 1. Proteomic analysis of strain LS1 and corresponding mutants.

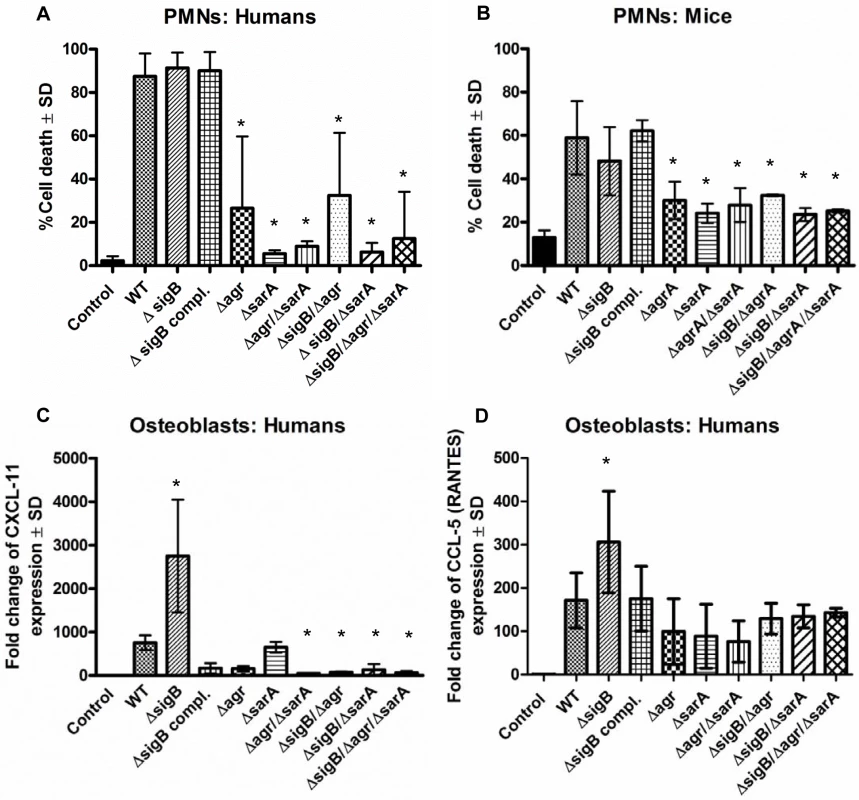

(A) Pie chart display of the proportion of secreted/ cell surface proteins displaying alterations in level in the different mutants compared to the wild type strain. Only proteins with SEED annotation are included and they are categorized according to SEED. Proteins displaying reduced and increased levels in the mutants compared to the wild type are displayed in shades of green and red, respectively. (B) Heat map of proteins which belong to the groups of adhesive and surface proteins or to secreted toxins. Log2-values of the ratios of intensity values of the wild type divided by those of the mutants from -4 to +4 are shown. Higher expression in the wild type versus the mutants is displayed in shades of green and higher expression in the mutants compared to the wild type in shades of red. Proteins displaying the same intensities in wild type and mutant are colored black. As secreted virulence factors are particularly directed against professional phagocytes, we tested the effect of bacterial supernatants on neutrophils (PMNs) isolated from humans and mice. In line with the proteomic data, only the strains with high levels of virulence factors (LS1, ΔsigB, ΔsigB compl.) caused cell death, whereas all other mutants with reduced levels of toxins induced significantly less cytotoxicity (Figs 2A and 2B and S2A–S2C). This effect was concentration dependent and revealed highest levels of cell death in response to supernatants of the sigB-mutant (S2C and S2D Fig). Next we analyzed levels of chemokine expression in cultured tissue cells, such as osteoblasts and endothelial cells, 48 h after infection by real time PCR (Fig 2C and 2D and S4C and S4D Fig) and 24 h after infection by ELISA-measurements (S3C and S3D Fig). In contrast to the wild-type strain, all double-and triple-mutants (including mutations in SigB) exhibited reduced cell activating activity, whereas the sigB-single-mutant often caused even more cell activation than the wild-type strain. Furthermore, these effects were independent of the bacterial background and of the infected host cell types, as they were reproduced with selected mutants generated in strain SH1000 (S3D Fig). All effects were equally present in bone and endothelial cells (S4C and S4D Fig) regardless of the observation that endothelial cells took up higher amounts of bacteria than osteoblasts (S4A Fig). Nevertheless, endothelial cells expressed in general lower levels of chemokines than osteoblasts (S4B Fig).

Fig. 2. The combined action of agr and sarA is required for inflammation and cytotoxicity in the acute stage of infection.

Cytotoxicity experiments and analysis of inflammatory host response were performed in polymorphonuclear cells (PMNs), human osteoblasts and endothelial cells using wild-type strain LS1 and their derivate mutants. (A, B) PMNs were freshly isolated form human blood (A) and bone marrow of Balb/C mice (B) and 1×106/0.5 ml cells were incubated with 5% v/v of bacterial supernatants for 1 h. Then cells were washed, stained with annexin V and propidium iodide and cell death was measured by flow cytometry. (C, D) Cultured osteoblasts were infected with S. aureus LS1 or their derivate mutants (MOI 50). After bacterial invasion (3 h) extracellular staphylococci were removed by washing and lysostaphin treatment and infected cells were incubated with culture medium for 48 h. To analyze host cell response the changes in the expression of the chemokine CXCL-11 and CCL-5 were measured by real-time PCR. Results demonstrate the relative increase in gene expression, compared to unstimulated cells (control: expression 1). The fold change is the normalized expression of each gene to housekeeping genes (β-actin and GAPDH). The values of all experiments represent the means ± SD of at least three independent experiments performed in duplicates. * P≤0.05 ANOVA comparing the effects induced by the wild-type strains and the corresponding mutants. Similar results were obtained with strain SH1000 and selected mutants (S2 Fig and S3 Fig). Taken together, these results suggest that the agr - and SarA-systems are required to mount an aggressive and cytotoxic phenotype during acute infection, while SigB appears to have a restraining function on virulence. Nevertheless, since double and triple mutants are weak in virulence, the interaction of SigB with the agr - and SarA-systems is not clear during acute infection.

SigB is required for SCV-formation, whereas the agr - and SarA-systems need to be silenced for intracellular persistence

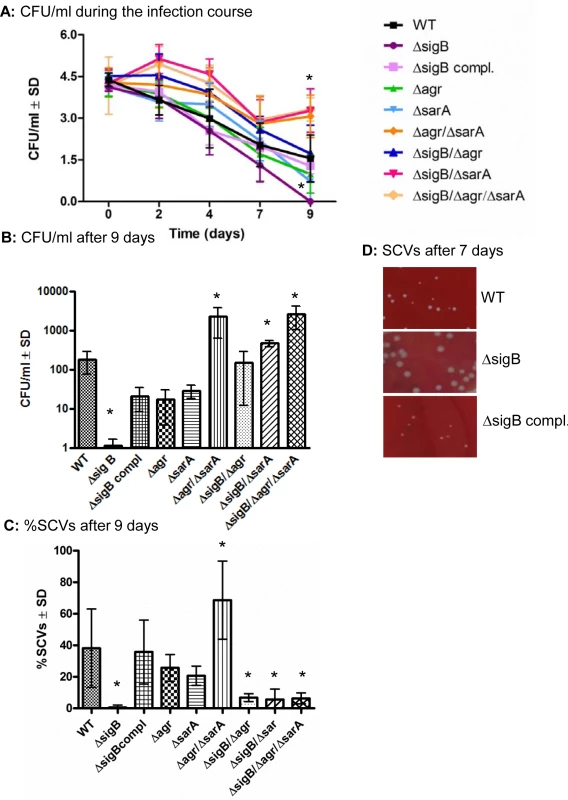

To test the function of the global regulatory systems in the course from acute to chronic infection, we infected osteoblast and endothelial cell cultures with wild-type and mutant strains and analyzed their ability to persist intracellularly for 9 days. All strains were invasive in osteoblasts to a similar extent (S5 Fig) and induced cell death ranging around 50% immediately after infection (S6A and S6B Fig). Yet, in the following 2–3 days the integrity of the infected cell monolayers were fully recovered and the rate of cell death was reduced to control levels (S6C Fig). In general the numbers of intracellular bacteria were decreased during the whole infection course (Figs 3A and S7A), but considerable differences between the strains appeared after several days (9 days, Figs 3B and S7B). The agr/sarA- and the sigB/sarA-double mutants as well as the triple mutant were able to persist within the intracellular location at significantly higher numbers (up to 100-fold) than the corresponding wild-type strain (Fig 3A and 3B). By contrast, the sigB-mutants were completely cleared from the host cells within 7–9 days, whereas this effect could be fully reversed by the complementation of sigB (Figs 3A and S7A). To test whether this effect is specific for sigB-mutants, we further tested mutants for other virulence or regulatory factors such as for sae and hla which did not reveal any differences in the numbers of intracellular persisting bacteria compared with the wild-type strain (S8 Fig). From our previous work we know that bacterial persistence is associated with dynamic SCV-formation. As recently described [9] we discovered an increased rate of SCV-formation after several days of intracellular bacterial persistence, whereby the recovered SCV were not stable, but the majority reverted back to the wild-type phenotype upon 2 to 5 subcultivating steps on agar plates. Interestingly, in the present study we found that all sigB-mutants completely failed to develop SCV phenotypes after 7 days of intracellular persistence (Fig 3C and 3D and S7C and S7D Fig). By analyzing the recovered colonies from sigB-mutants, we observed much less phenotypic diversity than in the wild-types and other mutants, as the plates revealed only uniform large white colonies. Again these effects could be reversed by complementation of the sigB-mutations with an intact sigB-operon, thus proving a clear and specific connection between the bacterial ability to form dynamic SCVs and the SigB-system.

Fig. 3. sigB promotes persistence and SCV-formation.

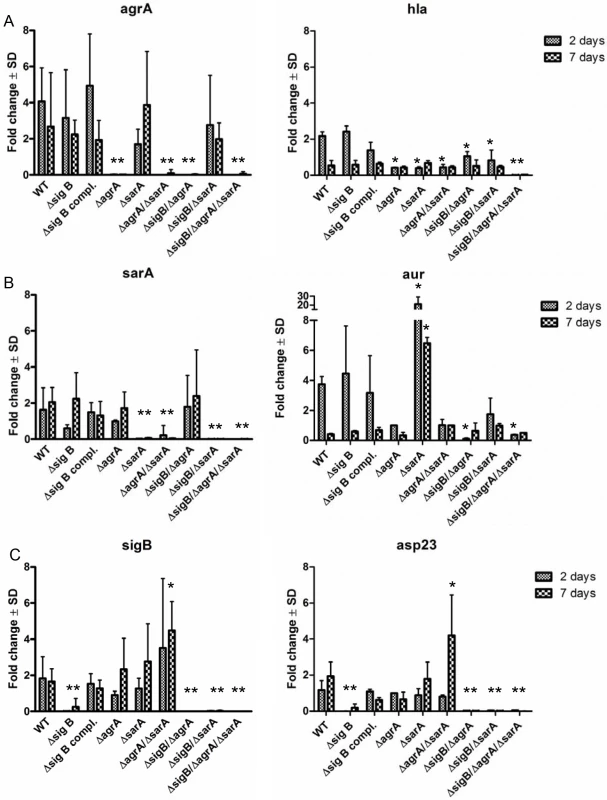

(A) Cultured osteoblasts were infected with S. aureus strain LS1 or the corresponding or complemented mutants and infected cells were analysed for up to 9 days. The numbers of viable intracellular persisting bacteria were determined every 2 days by lysing host cells, plating the lysates on agar plates and counting the colonies that have grown on the following day. (B) The results after 9 days are demonstrated separately. The results shown here are from osteoblast infection experiments, but similar results were obtained after infection of endothelial cells. (C) The percentage of small and very small (SCV) phenotypes (<5 and <10-fold smaller than those of the wild-type phenotypes, respectively) recovered (between 200 and 500 colonies examined in each sample) were determined after 7 days p.i. The values of all experiments represent the means ± SD of at least three independent experiments performed in duplicates. * P≤0.05 ANOVA test comparing the effects induced by the wild-type strains and the corresponding mutants. (D) Photographs of recovered colonies were performed after 7 days of infection of endothelial cells with strains LS1, LS1∆sigB or LS1∆sigB compl. Similar results were obtained when osteoblasts were infected with SH1000 and selected mutants (S7 Fig). To further explain the differential ability of the mutants to persist, we evaluated the expression of the global regulatory systems during the long course of the infection. To accomplish this, we extracted RNA from infected host cells (HUVEC; as they can host higher numbers of bacteria, S4A Fig) at day 2 and day 7 p.i. and measured the expression of agr, sarA and sigB and the related factors hla (regulated by agrA), aur (repressed by sarA [38]) and asp23 (regulated by sigB [39]) in the wild-type strain and corresponding mutants by quantitative real-time PCR (Fig 4). As expected high levels of both agrA and sarA were only expressed by the strains LS1, ΔsigB and ΔsigB compl. that resulted in high levels of hla expression in the acute phase of the infection. By contrast, the agr/sarA-double mutant expressed sigB and asp23 at significant higher levels than the wild-type strain during chronic infection (Fig 4) and was able to form higher numbers of SCV phenotypes (Figs 3C and S7C and S7D). Taken together, our results show that a concomitant downregulation of agrA and sarA promotes long-term intracellular persistence of S. aureus. SigB promotes chronic infections and is highly associated with the bacterial ability to form SCVs.

Fig. 4. Differential expression of the regulators agr, sarA and sigB during the course of host cell infection in wild-type LS1 and the corresponding mutants.

Endothelial cells were infected with S. aureus strain LS1 or the corresponding mutants as described in Fig 3A and infected cells were analysed for up to 7 days. Host cells infected with wild-type strain LS1 were lysed after 2 (acute phase) and 7 days (chronic phase) and the whole RNA was extracted and was used to determine changes in bacterial gene expression for agrA/hla (α-hemolysin) (A), sarA/aur (aureolysin) (B) and sigB/asp23 (C) during the course of infection by real-time PCR. The values of all experiments represent the mean ± SD of 5 independent experiments measured in triplicate. * P≤0.05 ANOVA comparing levels of gene expression in the wild-type strains and the corresponding mutants at each time point. The fold change is the result of normalized expression to the housekeeping genes gyr, aroE and gmk. Uninfected cells were used as controls (Control = 1). An active agr and/or SarA-system is required for lysosomal escape after host cell invasion

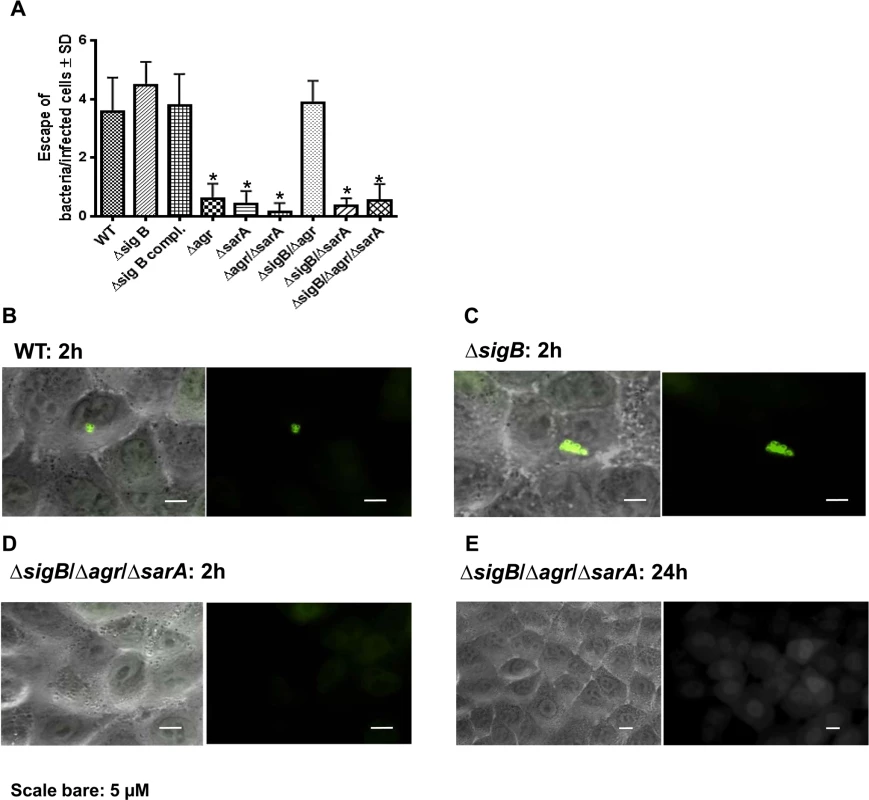

Only recently, phagosomal escape to the cytoplasm was reported for different S. aureus strains early after host cell invasion [13,40]. In a further approach we analyzed whether an early phagosomal escape is a prerequisite for persistence. Therefore we used a reporter recruitment technique based on the host cell line A549 genetically engineered to produce a phagosomal escape marker [13]. Within the first 2 h after host cell infection we detected phagosomal escape for the wild-type strain LS1, the sigB-, the sigB compl. - and the sigB/agr-mutants (Fig 5A–5D). These strains showed only weak changes and down-regulation of virulence factor expression by proteomic analysis compared with the wild-type (Fig 1A) and were not able to persist at high bacterial numbers (Fig 3B). As the single agr and sarA mutants readily lost their ability to translocate to the cytoplasm, apparently both agr - and sarA-regulated factors are required for the escape mechanism. The activity of SarA alone is sufficient only in case of a non-functional SigB-system, indicating a modulating role of SigB in virulence factor expression. Our results show that an early phagosomal escape is not required for persistence. Further on, mutants that persisted at high bacterial numbers did not escape to the cytoplasm. As phagosomal escape could not be detected at later stages of infection (up to 24 h; as shown in for the triple mutant; Fig 5E), it must be assumed that these mutants are not degraded within phagolysosomes and thus persist in phagosomes at high bacterial numbers.

Fig. 5. Phagosomal escape of wild-type strain LS1 and corresponding mutants after infection of the host cell construct A549YFP-CWT.

Phagosomal escape was measured 2 hours (A, B, C, D) and 24 hours (E) after infection with the strain LS1 or corresponding mutants in genetically engineered A549 cells. This reporter recruitment technique has been recently described [13]. To quantify the phagosomal escape for each strain 10 fields of view were evaluated respectively and the numbers of escaping bacteria were counted. The values represent the mean ± SD of 5 independent experiments measured.* P≤0.05 ANOVA comparing levels of gene expression in the acute and chronic stage. The combined dynamic action of the global regulators agr, SarA and SigB is required to efficiently establish an infection in vivo

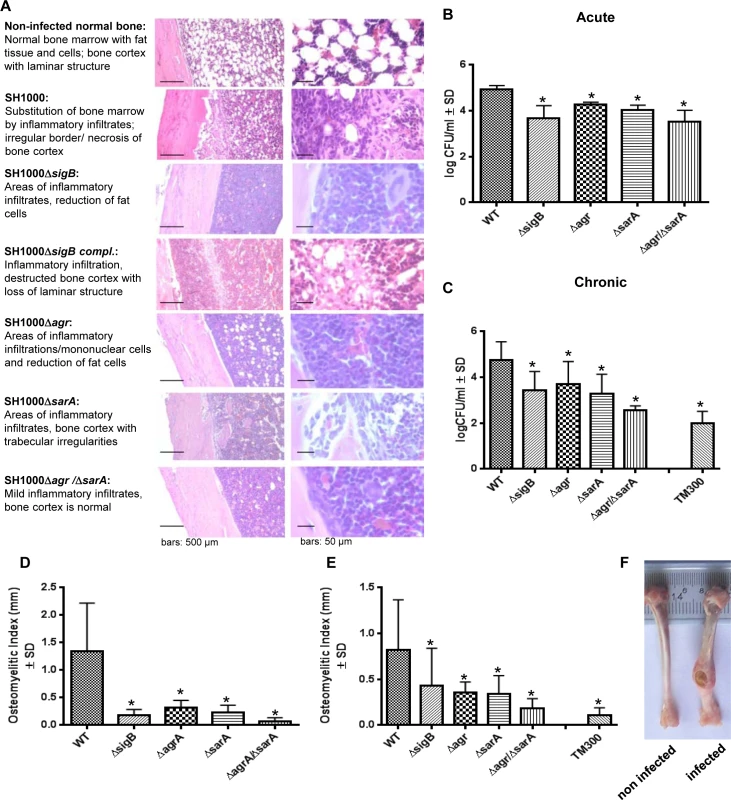

To test the ability of the wild-type and the mutant strains to establish an infection in vivo, we next performed experiments using a rat localized osteomyelitis model [41], where defined numbers of bacteria (1x106 CFU; strain SH1000 and mutants) were directly injected into the bones (Fig 6). Using this model we aimed to study the complex interaction of the bacterial strains with the immune response of the host organism. After 4 days (acute stage) and 14 weeks (chronic stage) groups of rats were sacrificed and the tibial bones were used for histology or morphometric analysis (osteomyelitis index; OI, Fig 6F) to assess for infection severity. After 4 days and 14 weeks the bacterial loads were determined by quantitative culture of bone homogenates. The data clearly demonstrated that the single mutants ΔsigB, Δagr and ΔsarA were found in lower numbers within the bones and caused less inflammation than the wild-type strain (Fig 6B–6E). We further tested as a selective double mutant the agr/sarA double mutant that persisted in high numbers within cells in culture experiments (Figs 3 and S7). By contrast, in the animal model we detected drastically reduced CFU and a lower osteomyelitis index in rats challenged with the agr/sarA double mutant when compared with rats infected with the parental wild-type strain. The agr/sarA-double mutant was found almost as avirulent as the low-pathogenic Staphylococcus carnosus strain TM300 [42], which lacks most S. aureus virulence factors (Fig 6B and 6C). Nevertheless, histological analysis 4 days p.i. revealed that in all experimental groups and control rats the bones were densely infiltrated with immune cells after S. aureus challenge (Fig 6A), indicating that both the wild-type and the mutant strains attract immune cells and sustain the infection. Only the wild-type strain, however, was able to settle and replicate at high bacterial numbers, to induce severe bone destruction and to develop into chronicity. These findings supports the hypothesis that regulators agr, SarA and SigB need to be functional to enable S. aureus to successfully survive during the whole infection process.

Fig. 6. The interplay of agr, sarA and sigB is required to settle and maintain an infection in a local rat chronic osteomyelitis model.

A local chronic osteomyelitis model was used to study the effects of wild-type SH1000 and corresponding mutants. (A) After 4 days of infection slices of bone tissue were performed for histology and stained by hematoxylin-eosin to detect the influx of immune cells to bone tissue. For each strain tested representative photomicrographs are shown in low and high magnification and typical histological features are described. (B, C) Bacterial persistence in host tissue was analyzed 4 days p.i. (acute) and 14 weeks p.i. (chronic) by plating homogenized bone tissue on agar plates and counting the CFU the following day. (D, E) The osteomyelitis index was measured 4 days p.i. (acute) and 14 weeks p.i. (chronic) from each infected tibiae in comparison with the non-infected tibiae from the same animal. The experiments were performed with 12 animals per group and the results shown are means ± SD. * P≤0.05 ANOVA test comparing persisting CFU and osteomyelitis index caused by wild-type SH1000 and the corresponding mutants. (F) Photographs of infected (wild-type SH1000) and non-infected tibiae recovered after 14 weeks. Discussion

S. aureus is one of the most frequent causes of osteomyelitis and endovascular infections that often take a therapy-refractory or chronic course. Many clinical studies show that persistent infections are highly associated with the SCV phenotype [4,43]. Only recently, we were able to demonstrate that the formation of dynamic SCVs is an integral part of the long-term infection process that enables the bacteria to hide inside host cells, but also to rapidly revert to the fully-aggressive wild-type phenotype, when leaving the intracellular location and causing a new episode of infection [9]. Therefore, the pathogen-host interaction must be very dynamic and most likely requires global transcriptional changes on the bacterial side to promote survival of the pathogen. This study was aimed at detecting regulatory factors that mediate this dynamic infection and adaptation strategies. To this purpose, we focused on a set of important S. aureus regulators/regulatory loci agr, SarA, and SigB that are linked together in a global regulatory network. Each one of these regulators/regulatory loci is involved in the control of the expression of many virulence factors such as adhesive and cytotoxic components. For our experiments we used various in vitro and in vivo infection models to analyze the impact and dynamics of the regulators from acute to chronic infection.

In models of acute infection we demonstrated that active agr- and SarA-systems are required to cause inflammation and cytotoxicity. Our results are in line with many published infection models, showing that both factors contribute to disease development [27,44–46]. We further confirmed that strains become almost avirulent, when both factors are inactive. In case of a single mutation, agr and sarA may partly compensate for each other [47], but the compensation is not sufficient in all functions, e.g., in phagosomal escape (Fig 5) and in in vivo infections (Fig 6). In the acute stage of infection the bacteria need to express a set of virulence factors, including toxins and exoenzymes, to fight against recruited immune cells [48] and to destroy and invade deep tissue structures at high bacterial numbers. Particularly toxins and cytotoxic factors are under the tight control of agr and sarA [19,47,49]. The role of SigB in acute infection is less clear. Inactivation of sigB in S. aureus has been reported to decrease infectivity in some murine infection models [50–52], but was ineffective in others [53,54]. In line with these conflicting findings, we observed on the one hand that single mutants in sigB express higher levels of toxins, e.g., α-toxin, and become even more virulent (Fig 2C and 2D and S2C and S2D Fig) suggesting a moderating role of sigB on the expression of secreted proinflammatory factors. On the other hand double mutants lacking sigB were almost avirulent (Fig 2C) indicating a further function of SigB within the regulatory network during acute inflammation. This is supported by recent work showing a fast and transient upregulation of sigB in the first hours following host cell invasion and the requirement of SigB for early intracellular growth [55].

In the longer course of the infection bacteria can be situated within host cells, like in the cell culture models. As almost all types of host cells contain killing and clearing machineries [10], the persisting bacteria need to develop mechanisms to resist degradation that can be achieved by two different pathways according to the results from our cell culture experiments:

Certain mutants that reveal significant metabolic changes including downregulation of virulence factors (Fig 1), and do not escape from the phagosomes after host cell invasion (Fig 5) can persist within their host cells partly at higher numbers than the wild-type phenotype (Fig 3). An example of this is the triple mutant ∆sigB∆agr∆sarA that fails to form SCVs, but is largely avirulent and can persist at high bacterial numbers. Recent work demonstrated that phagosomal escape is largely dependent on the agr-regulated phenol-soluble modulins (PSMs) [6,13], but further agr or sarA regulated factors could also be involved, as single mutants in agr or sarA were already compromised in their escape [56–58]. This mechanism of persistence is restricted to strains that lack expression of agr and/or sarA-regulated virulence factors. Our results indicate that these strains are less prone to degradation and can “passively” persist inside host cells, possibly within their initial phagosomes after host cell invasion even without forming SCVs.

Further on, persistence is also possible when bacteria express virulence factors and escape from their phagosomes to the cytoplasm. Persistence obviously requires an adaptation to the intracellular environment that could be attributed to the function of SigB during the long course of the infection. SigB is an important staphylococcal transcription factor that is associated with various types of stress-responses [31,33,35,59], was shown to be upregulated in stable clinical SCVs and was associated with increased intracellular persistence [60]. According to our results SigB is also involved in stress-resistance that promotes “active” intracellular survival during long-term persistence: The first important finding is that ΔsigB-mutants were not able to persist, as they were completely cleared by their host cells within 9 days (Fig 3B). Additionally, the agr/sarA-double mutants that were found at the highest numbers during long-term persistence (Figs 3B and S7B) displayed the highest levels of sigB expression (Fig 4). Finally, a result of major significance is that SigB is required for dynamic SCV formation, as all mutants deficient in sigB were not able to form SCV-phenotypes (Figs 3C and S7C) and agr/sarA-double mutants that highly expressed sigB (Fig 4) developed the highest levels of SCVs. Only recently SigB was described as an important virulence factor in stable SCVs that mediates biofilm formation and promotes intracellular bacterial growth [61]. Yet, in our work the recovered SCVs were not stable, but rapidly reverted back to the wild-type phenotype upon subcultivation. Consequently, we describe the formation of dynamic SCVs for persistence as an additional central function that is dependent on an intact SigB-system.

Taken together, our results demonstrated that intracellular bacterial persistence is promoted by the silencing of agr - and sarA-regulated factors and/or requires an intact SigB-system. Although strains with deletions in the agr and/or sarA-system were able to persist at high bacterial numbers in cell culture systems that lack most components of a functioning immune system, they showed severe disadvantages in the in vivo model, as they were unable to defend themselves from invading immune cells (Fig 2A and 2B) and were rapidly cleared from the infection focus (Fig 6A and 6B). Consequently, SigB represents a crucial factor to dynamically adapt fully virulent wild-type strains to switch to long-term persistent phenotypes. SigB was described to turn down the agr system [36], which is most likely responsible for the enhanced inflammatory activity. The downregulated agr-system helps the bacteria to form biofilm [62] and silences aggressiveness for persistence within the host cell [63]. This expression pattern (high sigB and low agr) of global regulators appears to be characteristic for SCVs and seems to represent a general adaptation response, as it had been described for stable SCVs generated by aminoglycoside treatment as well [35]. Yet, the varying stress conditions encountered by S. aureus on its way to the intracellular location are less defined and many questions remain to be answered to fully elucidate the complete dynamic bacterial adaption strategies: e.g., (i) which intracellular conditions affect the staphylococcal regulatory factors? (ii) which staphylococcal regulatory factor(s) is/are directly influenced by the intracellular milieu (agr or sigB or further systems, such as the mazEF toxin-antitoxin module [64])? (iii) How are the changes of regulatory factors transferred to an increased SCV formation? (iv) which factors of the SigB regulon are required for persistence [65]? (v) Does SigB increase bacterial resistance against antibiotics? All questions require extensive additional laboratory work to decipher the bacterial adaptation mechanisms in more detail.

In our study we used different bacterial backgrounds and mutants, as well as different in vitro and in vivo infection models to demonstrate that bacteria apply general adaption strategies via the crosstalk of regulatory factors with a central function for SigB. By this means, bacteria can rapidly react to changing environmental conditions and dynamically adjust their virulence factor expression at any time of the infection. As the regulatory network involving SigB appears to be the central factor that enables the bacteria to persist and cause chronic infections, it represents a novel therapeutic target for prevention and treatment of chronic and recurrent infection.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial strains used in the study and generation of bacterial mutants

The bacterial strains and mutants used in this study are listed in Supp. S1 Table. All the experiments were performed with wild type and mutants in the background of S. aureus LS1 and S. aureus SH1000. LS1 is a murine arthritis isolate that has been used in infection models before [66]. The strain SH1000 has a complementation of the rbsU gene in the strain 8325–4 which is deficient in SigB activity (a stress-induced activity) due to a mutation in the rsbU gene. This gene encodes for a phosphatase required for the release of the sigma factor SigB from inhibition by its anti-sigma factor RsbW. To create a strain with an intact SigB-dependent stress response, the rsbU gene was restored in S. aureus 8325–4, with the resulting strain called SH1000 [66].The antibiotic resistance cassette-tagged agr, rsbUVWsigB, and sarA mutations of RN6911 [67], IK181 [68] and ALC136 [69] were transduced into LS1 using phages 11, 80α and 85, respectively. ΔrsbUVWsigB derivatives were cis-complemented by phage transduction with a resistance cassette-tagged intact sigB operon obtained from strain GP268 [70] using phage 80α. The sarA mutant of SH1000 was constructed by replacing the sarA gene with an erythromycin resistance cassette. The sigB mutant of SH1000 was constructed by transducing the sigB mutation (sigB::Tn551) from RUSA168 into SH1000.

Preparation of protein extracts for proteome analysis of the extracellular protein fraction

The strains were cultivated in tryptic soy broth (TSB) at 37°C with linear shaking at 100 rpm in a water bath (OLS200, Grant Instruments, England). Strains were grown in two sets. In the first set the wild type and the ∆sigB, ∆agr, ∆sarA and ∆agr/∆sarA mutants were cultured and in a second set the wild type and the ∆sigB∆agr, ∆sigB∆sarA and ∆sigB∆agr∆sarA mutants were cultured. The wild type always served as control. During exponential growth phase bacteria were pelleted by centrifugation and culture supernatants were mixed with 10% final concentration of TCA and proteins precipitated at 4°C overnight. Pelleted proteins were washed five times with 70% ethanol and then incubated for 30 min at 21°C and mixed at 600 rpm in a thermomixer (Eppendorf, Germany). Afterwards, pellets were washed once with 100% ethanol and dried in a speed vacuum centrifuge (Concentrator 5301, Eppendorf, Germany). Subsequently, protein pellets were dissolved in a suitable volume of 1x UT buffer (8 M urea and 2 M thiourea) and incubated for 1h at 21°C with shaking at 600 rpm in a thermomixer (Eppendorf, Germany). No soluble components were pelleted via centrifugation. Protein concentration was determined according to Bradford [71]. 4 μg of protein were reduced and alkylated with Dithiothreitol and Iodoacetamid prior to digestion with Trypsin.

Proteome analysis by mass spectrometry and analysis of data

Peptides were purified and desalted using μC18 ZipTip columns and dried in a speed vacuum centrifuge (Concentrator plus, Eppendorf, Germany). Dried peptides were dissolved in LC buffer A (2% ACN, in water with 0.1% Acetic acid) and subsequently analysis by mass spectrometry was performed on a Proxeon nLC system (Proxeon, Denmark) connected to a LTQ-Orbitrap Velos - mass spectrometer (ThermoElectron, Germany). For LC separation the peptides were enriched on a BioSphere C18 pre-column (NanoSeparations, Netherlands) and separated using an Acclaim PepMap 100 C18 column (Dionex, USA). For separation a 86-minute gradient was used with a solvent mixture of buffer A (2% Acetonitrile in water with 0.1% Acetic acid) and B (ACN with 0.1% acetic acid): 0–2% for 1min, 2–5% for 1 min, 5–25% for 59 min, 25–40% for 10 min, 40–100% for 8 min for buffer B. The peptides were eluted with a flow rate of 300 nL/min. The full scan MS spectra were carried out using a FTMS analyzer with a mass range of m/z 300 to 1700. Data were acquired in profile mode with positive polarity. The method used allowed sequential isolation of the top 20 most intense ions for fragmentation using collision induced dissociation (CID). A minimum of 1000 counts were activated for 10 ms with an activation of q = 0.25, isolation width 2 Da and a normalized collision energy of 35%. The charge state screening and monoisotopic precursor selection was rejecting +1 and +4 charged ions. Target ions already selected for MS/MS were excluded for next 60 seconds.

Analysis of MS data was performed with Rosetta Elucidator version 3.3.0.1 (Rosetta Biosoftware, MA, USA). An experimental definition for differential label free quantification was created with default settings: instrument mass accuracy of 5 ppm, spectral alignment search distance of 4 minutes, peak time width minimum of 0.1. For identification the S. aureus NCTC 8325 FASTA sequence in combination with SEQUEST/ Sorcerer was used. Oxidation of methionine, carbamidomethylation and zero missed cleavages were specified as variable modifications. After identification an automatic Peptide/Protein Tellers annotation was performed and only Peptide Teller results greater than 0.8 were used. At least two peptides per protein or one peptide with protein sequence coverage of at least 10% were necessary for reliable protein identification.

Protein intensities received with the Rosetta Elucidator software were further processed using Genedata Analyst version 7.6 (Genedata AG, Basel, Switzerland). Protein intensities were normalized using the central tendency normalization with a dynamic target and the median as central tendency. For relative quantification the ratio of the protein intensities between the wild type and the respective mutants from set one or two were calculated. A protein with a ratio of ≥2 was assigned to be upregulated in the wild type and with a ratio of ≤0.5 was assigned to be upregulated in the mutant strain. For prediction of protein localization the PSORT database was used (PSORTdb 3.0, http://db.psort.org/browse/genome?id=9009). Furthermore, for categorizing the proteins into subgroups The SEED (Overbeek et al., Nucleic Acids Res 33(17)) annotation for S. aureus NCTC8325 was used. A heat map with log2 ratios of the wild type versus the respective mutants was created using the package heatmap.plus version 1.3 in R version 2.15.1 (http://www.R-project.org).

Preparation of bacterial strains and bacterial supernatants

For cell culture experiments, bacteria were grown overnight in 15 ml of brain-heart infusion (BHI) with shaking (160 rpm) at 37°C. The following day, bacteria were two times washed with PBS and were adjusted to OD = 1 (578nm). Bacterial supernatants were prepared as described [21]. Briefly, bacteria were grown in 5 ml of brain-heart-infusion broth (Merck, Germany) in a rotator shaker (200 rpm) at 37°C for 17 h and pelleted for 5 min at 3350 g. Supernatants were sterile-filtered through a Millex-GP filter unit (0.22 μm; Millipore, Bedford, MA) and added to the cell culture medium in the indicated concentrations.

Growth rates and generation time (growth curves)

For growth curves, Staphylococcus aureus wild-type LS1, SH1000 and their respective mutants were grown overnight in 15ml of Mueller Hinton infusion (MH) with shaking (160rpm) at 37°C. The following day, 100ml of MH were inoculated with each strain in order to obtain the starting optical density 0,05 (578nm). The growth of each strain was monitored spectrophotometrically (578nm) and by plating on blood agar for counting of CFU every hour during 8h. The growth rate (μ, growth speed) and the generation time (g) for each strain used in this study were calculated according the followings formulas [72].

μ = growth rate

g = generation time

N = final population

N0 = initial population

t = final time

t0 = initial time

Isolation and culture of different cell types and long-term cell culture infection models

Various types of host cells, namely primary isolated human umbilical venous endothelial cells (HUVECs) and primary isolated human osteoblasts were cultivated as outlined before [73–75] and were infected with different S. aureus strains as previously described [14]. Briefly, primary cells were infected with an MOI (multiplicity of infection) of 50. After 3 h cells were washed and lysostaphin (20 μg/ml) was added for 30 min to lyse all extracellular or adherent staphylococci, then fresh culture medium was added to the cells. The washing, the lysostaphin step and medium exchange was repeated daily to remove all extracellular staphylococci, which might have been released from the infected cells. To detect live intracellular bacteria at different time points post infection (p.i.) host cells were lysed in 3 ml H2O (for 25cm2 bottles) or 20 ml H2O (for 175cm2 bottles). To determine the number of colony forming units (CFU), serial dilutions of the cell lysates were plated on blood agar plates and incubated overnight at 37°C. The colony phenotypes were determined on blood agar plates by a Colony Counter Biocount 5000 (Biosys, Karben, Germany).

Phagosomal escape assays

A549 cells stably expressing the escape marker YFP-CWT in the cytoplasm were generated by transduction with lentiviral particles as described [76]. Transductants were passaged three times and subsequently selected by FACS. The phagosomal escape signal is based on the recruitment of YFP-CWT to the staphylococcal cell wall upon rupture of the phagosomal membrane barrier. Recruitment thereby is mediated by the cell wall targeting domain of the S. simulans protease lysostaphin [77]. Accumulation of the fusion protein YFP-CWT was recorded by fluorescence microscopy. For this the A549 YFP-CWT cells were infected in imaging dishes with coverglass bottom (MoBiTec, Göttingen, Germany) with the S. aureus LS1 wild type strain or the corresponding mutants for 1 h, followed by lysostaphin treatment to remove all extracellular bacteria. 2 h post infection the YFP-signal was observed with a Zeiss Axiovert 135 TV microscope (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany) equipped with a 50 W HBO mercury short-arc lamp and a Zeiss filter set (excitation BP 450–490 nm, beam splitter FT 510 nm, emission LP 515 nm). For quantitative assays a 100×/NA 1.3 plan-neofluar objective (field of view 25mm) was used. Data were acquired with an AxioCam MRm camera and processed using Zeiss AxioVision software. 10 fields of view were recorded per experiment and phagosomal escape was enumerated for 5 independent experiments per strain.

Isolation and culture of PMNs

Human polymorphonuclear cells (PMNs) were freshly isolated from Na-citrate-treated blood of healthy donors. For neutrophil-isolation, dextran-sedimentation and density gradient centrifugation using Ficoll-Paque Plus (Amersham Bioscience) was used according to the manufacturer's instruction. Cell purity was determined by Giemsa staining and was always above 99%. PMNs were suspended to a final density of 1×106 cells/0.5 ml in RPMI 1640 culture medium (PAA Laboratories GmbH) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FCS (PAA Laboratories GmbH) and immediately used for the experiments. All incubations were performed at 37°C in humidified air with 5% CO2.

To measure cell death induction 1x106 cells/0.5 ml PMNs were cultured at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere in 24-well plates and bacterial supernatants were added as indicated. After 1 h cell death induction was analyzed as described previously [78,79].

Cell death assays in endothelial cells and osteoblasts

For the flow cytometric invasion assay, primary human osteoblasts or endothelial cells were plated at 2x105 cells in 12-well plates the day before the assay. Cells were washed with PBS, then cells were incubated with 1 ml of 1% HSA, 25 mM HEPES (pH 7.4) in F-12 medium (Invitrogen). The bacteria were grown in BHI, washed and the bacterial suspension (OD 1, 540 nm) was prepared and was added to cells. After the lysostaphin step the infected cells were incubated for 24 h and cell death assays were performed by measuring the proportion of hypodiploid nuclei as described [8].

To measure cell death during the bacterial persistence, this protocol was performed every two days.

Hemolysis assay

Hemolysis analysis was performed as described previously with some modifications [80]. The lysis efficacies of human red blood cells were measured using whole culture supernatants of S. aureus LS1, SH1000 and their respective mutants. Briefly, S. aureus cells were cultured in BHI for 17 h at 250rpm. Staphylococcal cells were centrifuged and the supernatants were used for measuring hemolytic activity. Supernatants (100μL) were added to 100μl human red blood cells (previously prepared, see preparation of erythrocytes). To determine hemolytic activities, the mixtures of blood and S. aureus were incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes. Supernatants were collected by centrifugation at 1000g for 5 min and optical densities were measured at 570nm in an ELISA plate reader. The strain S. aureus Wood46 was used as a positive control.

Preparation of erythrocytes

A volume of 32ml blood was mixed with 8ml sodium citrate; 20ml Dextran was added and the mix was incubated for 45–60 minutes to form the gradient sedimentation. The white blood cells were removed from the top layer and the erythrocytes were prepared in a 1.4% solution in PBS. In the mixture with staphylococcal supernatant, the final concentration was approximately 0.7% v/v.

These results and the description of the method was added in the supporting information of our manuscript (S1C Fig).

Measurement of cytokines release

For measurement of cytokine release, osteoblasts were seeded in 12-well plates and stimulated with live staphylococci as described above. After the lysostaphin step, cells were washed and incubated with new culture medium for 24 h. Conditioned media were centrifuged to remove cells and cellular debris, and samples were frozen at 20°C until levels of cytokines and chemokines were measured. The levels of RANTES [regulated on activation of normal T cell expressed and secreted] was measured using immunoassays from RayBiotech according to the manufacturer`s description. Results are given as absolute values (ng/ml) of two independent experiments performed in duplicates. Statistical analysis was performed using the ANOVA test.

Rat chronic osteomyelitis model

Outbred Wistar adult rats (groups of 10–12 rats) weighing 250–350 g were anesthetized with ketamine/xylazine. The left tibia was exposed and a hole made with a high-speed drill using a 0.4 mm diameter bit. Each tibia was injected with a 5 μl suspension containing 1x106 CFU of bacteria suspended in fibrin glue (Tissucol kit 1 ml, Baxter Argentina-AG Viena, Austria). Groups of rats were sacrificed at 4 days or 14 weeks after intratibial challenge by exposure to CO2. Both left and right tibias were removed and morphometrically assessed by measuring the Osteomyelitic Index (OI) as described previously [41]. Both epiphysis were cut off from the infected tibias and 1 cm bone segments involving the infected zone were crushed and homogenized. Homogenates were quantitatively cultured overnight on trypticase soy agar and the number of CFU was determined. The OI and the S. aureus CFU counts from each experimental group (infected and control) were compared.

Extraction of RNA and real-time PCR

For RNA extraction, we used the kit RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen). The RNA extraction was performed following the manufacture instruction and the suggestions of the protocol described by Garzoni et al. [81].

All the primers used in this study are listed in Supp. S2 Table. Real-time PCR was performed by using the RNA isolated from infected cells, infected tissues or different bacterial isolates. The cDNA was obtained using the kit QuantiTect reverse transcription (Qiagen) and iQSYBR Green Supermix (BIO-RAD) was used. The reaction mixtures were incubated for 15 min at 95°C followed by 40 cycles of 15 s at 95°C, 30 s at 55°C and 30 s at 72°C using the iCycler from BIO-RAD. PCR efficiencies, melting-curve analysis and expression rates were calculated with the BIO-RAD iQ5 Software.

In order to analyze the expression of bacterial and host cell genes, respectively, the primers listed in S2 Table were used [14,63]. The expression analysis experiments were performed using the software CFX Manager software which calculates the normalized expression ΔΔCT (relative quantity of genes of interest is normalized to relative quantity of the reference genes across samples). The genes used as housekeeping genes to analyze the chemokine expression were GAPDH and B-actin. As controls we used uninfected host cells. For bacterial factors, we used as housekeeping genes aroE, gyrB and gmk. The results shown in each graph are normalized to that control (control expression = 1).

Ethics statement

The isolation of human cells and the infection with clinical strains were approved by the local ethics committee (Ethik-Kommission der Ärztekammer Westfalen-Lippe und der Medizinischen Fakultät der Westfälischen Wilhelms-Universität Münster). For our study, written informed consent was obtained (Az. 2010-155-f-S). Taking of blood samples from humans and animals and cell isolation were conducted with approval of the local ethics committee (2008-034-f-S; Ethik-Komission der Ärztekammer Westfalen-Lippe und der Medizinischen Fakultät der Westfälischen Wilhelms-Universität Münster). Human blood samples were taken from healthy blood donors, who provided written informed consent for the collection of samples and subsequent neutrophil isolation and analysis.

For the local osteomyelitis model care of the rats was in accordance with the guidelines set forth by the National Institutes of Health [82]. The experimental protocol involving rats in the experiments was approved by the Institutional Committee for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (CICUAL), School of Medicine, University of Buenos Aires (resolution CD 2361–11).

Statistical analysis

The relationship between WT and all the different mutants was established by the one way ANOVA test with the Dunnett multi-comparison post-test. Significance was calculated using the GraphPad Prism 6.0 software and results were considered significant at P = 0.05.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. Lowy FD (1998) Staphylococcus aureus infections. N Engl J Med 339 : 520–32. 9709046

2. Lew DP, Waldvogel FA (2004) Osteomyelitis. Lancet 364 : 369–379. 15276398

3. Werdan K, Dietz S, Löffler B, Niemann S, Bushnaq H et al. (2014) Mechanisms of infective endocarditis: pathogen-host interaction and risk states. Nat Rev Cardiol 11 : 35–50. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2013.174 24247105

4. Proctor RA, von Eiff C, Kahl BC, Becker K, McNamara P et al. (2006) Small colony variants: a pathogenic form of bacteria that facilitates persistent and recurrent infections. Nat Rev Microbiol 4 : 295–305. 16541137

5. Otto M (2014) Staphylococcus aureus toxins. Curr Opin Microbiol 17 : 32–37. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2013.11.004 24581690

6. Wang R, Braughton KR, Kretschmer D, Bach TH, Queck SY et al. (2007) Identification of novel cytolytic peptides as key virulence determinants for community-associated MRSA. Nat Med 13 : 1510–1514. 17994102

7. Ellington JK, Reilly SS, Ramp WK, Smeltzer MS, Kellam JF et al. (1999) Mechanisms of Staphylococcus aureus invasion of cultured osteoblasts. Microb Pathog 26 : 317–323. 10343060

8. Haslinger-Löffler B, Kahl BC, Grundmeier M, Strangfeld K, Wagner B et al. (2005) Multiple virulence factors are required for Staphylococcus aureus-induced apoptosis in endothelial cells. Cell Microbiol 7 : 1087–1097. 16008576

9. Tuchscherr L, Medina E, Hussain M, Völker W, Heitmann V et al. (2011) Staphylococcus aureus phenotype switching: an effective bacterial strategy to escape host immune response and establish a chronic infection. EMBO Mol Med 3 : 129–141. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201000115 21268281

10. Amano A, Nakagawa I, Yoshimori T (2006) Autophagy in innate immunity against intracellular bacteria. J Biochem 140 : 161–166. 16954534

11. Deretic V, Levine B (2009) Autophagy, immunity, and microbial adaptations. Cell Host Microbe 5 : 527–549. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.05.016 19527881

12. Sinha B, Fraunholz M (2010) Staphylococcus aureus host cell invasion and post-invasion events. Int J Med Microbiol 300 : 170–175. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2009.08.019 19781990

13. Grosz M, Kolter J, Paprotka K, Winkler AC, Schafer D et al. (2013) Cytoplasmic replication of Staphylococcus aureus upon phagosomal escape triggered by phenol-soluble modulin alpha. Cell Microbiol.

14. Tuchscherr L, Heitmann V, Hussain M, Viemann D, Roth J et al. (2010) Staphylococcus aureus Small-Colony Variants Are Adapted Phenotypes for Intracellular Persistence. J Infect Dis 202 : 1031–1040. doi: 10.1086/656047 20715929

15. Bayer MG, Heinrichs JH, Cheung AL (1996) The molecular architecture of the sar locus in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol 178 : 4563–70. 8755885

16. Bischoff M, Dunman P, Kormanec J, Macapagal D, Murphy E et al. (2004) Microarray-based analysis of the Staphylococcus aureus sigmaB regulon. J Bacteriol 186 : 4085–4099. 15205410

17. Cheung AL, Nishina KA, Trotonda MP, Tamber S (2008) The SarA protein family of Staphylococcus aureus. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 40 : 355–361. 18083623

18. Recsei P, Kreiswirth B, O'Reilly M, Schlievert P, Gruss A et al. (1986) Regulation of exoprotein gene expression in Staphylococcus aureus by agar. Mol Gen Genet 202 : 58–61. 3007938

19. Novick RP, Geisinger E (2008) Quorum sensing in staphylococci. Annu Rev Genet 42 : 541–564. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.42.110807.091640 18713030

20. Queck SY, Jameson-Lee M, Villaruz AE, Bach TH, Khan BA et al. (2008) RNAIII-independent target gene control by the agr quorum-sensing system: insight into the evolution of virulence regulation in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol Cell 32 : 150–158. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.08.005 18851841

21. Bantel H, Sinha B, Domschke W, Peters G, Schulze-Osthoff K et al. (2001) alpha-Toxin is a mediator of Staphylococcus aureus-induced cell death and activates caspases via the intrinsic death pathway independently of death receptor signaling. J Cell Biol 155 : 637–48. 11696559

22. Bhakdi S, Tranum-Jensen J (1991) Alpha-toxin of Staphylococcus aureus. Microbiol Rev 55 : 733–751. 1779933

23. Rasigade JP, Trouillet-Assant S, Ferry T, Diep BA, Sapin A et al. (2013) PSMs of hypervirulent Staphylococcus aureus act as intracellular toxins that kill infected osteoblasts. PLoS ONE 8: e63176. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063176 23690994

24. Cheung AL, Koomey JM, Butler CA, Projan SJ, Fischetti VA (1992) Regulation of exoprotein expression in Staphylococcus aureus by a locus (sar) distinct from agr. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 89 : 6462–6. 1321441

25. Cheung AL, Bayer AS, Zhang G, Gresham H, Xiong YQ (2004) Regulation of virulence determinants in vitro and in vivo in Staphylococcus aureus. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 40 : 1–9. 14734180

26. Blevins JS, Elasri MO, Allmendinger SD, Beenken KE, Skinner RA et al. (2003) Role of sarA in the pathogenesis of Staphylococcus aureus musculoskeletal infection. Infect Immun 71 : 516–523. 12496203

27. Cheung AL, Eberhardt KJ, Chung E, Yeaman MR, Sullam PM et al. (1994) Diminished virulence of a sar-/agr - mutant of Staphylococcus aureus in the rabbit model of endocarditis. J Clin Invest 94 : 1815–1822. 7962526

28. van Wamel W., Xiong YQ, Bayer AS, Yeaman MR, Nast CC et al. (2002) Regulation of Staphylococcus aureus type 5 capsular polysaccharides by agr and sarA in vitro and in an experimental endocarditis model. Microb Pathog 33 : 73–79. 12202106

29. Beenken KE, Blevins JS, Smeltzer MS (2003) Mutation of sarA in Staphylococcus aureus limits biofilm formation. Infect Immun 71 : 4206–4211. 12819120

30. Blevins JS, Gillaspy AF, Rechtin TM, Hurlburt BK, Smeltzer MS (1999) The Staphylococcal accessory regulator (sar) represses transcription of the Staphylococcus aureus collagen adhesin gene (cna) in an agr-independent manner. Mol Microbiol 33 : 317–326. 10411748

31. Hecker M, Reder A, Fuchs S, Pagels M, Engelmann S (2009) Physiological proteomics and stress/starvation responses in Bacillus subtilis and Staphylococcus aureus. Res Microbiol 160 : 245–258. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2009.03.008 19403106

32. van Schaik W., Abee T (2005) The role of sigmaB in the stress response of Gram-positive bacteria—targets for food preservation and safety. Curr Opin Biotechnol 16 : 218–224. 15831390

33. Horsburgh MJ, Aish JL, White IJ, Shaw L, Lithgow JK et al. (2002) sigmaB modulates virulence determinant expression and stress resistance: characterization of a functional rsbU strain derived from Staphylococcus aureus 8325–4. J Bacteriol 184 : 5457–5467. 12218034

34. Chen HY, Chen CC, Fang CS, Hsieh YT, Lin MH et al. (2011) Vancomycin activates sigma(B) in vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus resulting in the enhancement of cytotoxicity. PLoS ONE 6: e24472. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024472 21912698

35. Mitchell G, Brouillette E, Seguin DL, Asselin AE, Jacob CL et al. (2010) A role for sigma factor B in the emergence of Staphylococcus aureus small-colony variants and elevated biofilm production resulting from an exposure to aminoglycosides. Microb Pathog 48 : 18–27. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2009.10.003 19825410

36. Bischoff M, Entenza JM, Giachino P (2001) Influence of a functional sigB operon on the global regulators sar and agr in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol 183 : 5171–5179. 11489871

37. Ahmed S, Meghji S, Williams RJ, Henderson B, Brock JH et al. (2001) Staphylococcus aureus fibronectin binding proteins are essential for internalization by osteoblasts but do not account for differences in intracellular levels of bacteria. Infect Immun 69 : 2872–2877. 11292701

38. Dunman PM, Murphy E, Haney S, Palacios D, Tucker-Kellogg G et al. (2001) Transcription profiling-based identification of Staphylococcus aureus genes regulated by the agr and/or sarA loci. J Bacteriol 183 : 7341–7353. 11717293

39. Gertz S, Engelmann S, Schmid R, Ohlsen K, Hacker J et al. (1999) Regulation of sigmaB-dependent transcription of sigB and asp23 in two different Staphylococcus aureus strains. Mol Gen Genet 261 : 558–566. 10323238

40. Giese B, Glowinski F, Paprotka K, Dittmann S, Steiner T et al. (2011) Expression of delta-toxin by Staphylococcus aureus mediates escape from phago-endosomes of human epithelial and endothelial cells in the presence of beta-toxin. Cell Microbiol 13 : 316–329. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2010.01538.x 20946243

41. Lattar SM, Noto LM, Denoel P, Germain S, Buzzola FR et al. (2014) Protein antigens increase the protective efficacy of a capsule-based vaccine against Staphylococcus aureus in a rat model of osteomyelitis. Infect Immun 82 : 83–91. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01050-13 24126523

42. Rosenstein R, Götz F (2010) Genomic differences between the food-grade Staphylococcus carnosus and pathogenic staphylococcal species. Int J Med Microbiol 300 : 104–108. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2009.08.014 19818681

43. Proctor RA, van Langevelde P., Kristjansson M, Maslow JN, Arbeit RD (1995) Persistent and relapsing infections associated with small-colony variants of Staphylococcus aureus. Clin Infect Dis 20 : 95–102. 7727677

44. Abdelnour A, Arvidson S, Bremell T, Ryden C, Tarkowski A (1993) The accessory gene regulator (agr) controls Staphylococcus aureus virulence in a murine arthritis model. Infect Immun 61 : 3879–3885. 8359909

45. Gillaspy AF, Hickmon SG, Skinner RA, Thomas JR, Nelson CL et al. (1995) Role of the accessory gene regulator (agr) in pathogenesis of staphylococcal osteomyelitis. Infect Immun 63 : 3373–3380. 7642265

46. Nilsson IM, Bremell T, Ryden C, Cheung AL, Tarkowski A (1996) Role of the staphylococcal accessory gene regulator (sar) in septic arthritis. Infect Immun 64 : 4438–4443. 8890189

47. Chan PF, Foster SJ (1998) Role of SarA in virulence determinant production and environmental signal transduction in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol 180 : 6232–6241. 9829932

48. Anwar S, Prince LR, Foster SJ, Whyte MK, Sabroe I (2009) The rise and rise of Staphylococcus aureus: laughing in the face of granulocytes. Clin Exp Immunol 157 : 216–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2009.03950.x 19604261

49. Zielinska AK, Beenken KE, Joo HS, Mrak LN, Griffin LM et al. (2011) Defining the strain-dependent impact of the Staphylococcal accessory regulator (sarA) on the alpha-toxin phenotype of Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol 193 : 2948–2958. doi: 10.1128/JB.01517-10 21478342

50. Herbert S, Ziebandt AK, Ohlsen K, Schafer T, Hecker M et al. (2010) Repair of global regulators in Staphylococcus aureus 8325 and comparative analysis with other clinical isolates. Infect Immun 78 : 2877–2889. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00088-10 20212089

51. Jonsson IM, Arvidson S, Foster S, Tarkowski A (2004) Sigma factor B and RsbU are required for virulence in Staphylococcus aureus-induced arthritis and sepsis. Infect Immun 72 : 6106–6111. 15385515

52. Lorenz U, Huttinger C, Schafer T, Ziebuhr W, Thiede A et al. (2008) The alternative sigma factor sigma B of Staphylococcus aureus modulates virulence in experimental central venous catheter-related infections. Microbes Infect 10 : 217–223. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2007.11.006 18328762

53. Depke M, Burian M, Schafer T, Broker BM, Ohlsen K et al. (2012) The alternative sigma factor B modulates virulence gene expression in a murine Staphylococcus aureus infection model but does not influence kidney gene expression pattern of the host. Int J Med Microbiol 302 : 33–39. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2011.09.013 22019488

54. Nicholas RO, Li T, McDevitt D, Marra A, Sucoloski S et al. (1999) Isolation and characterization of a sigB deletion mutant of Staphylococcus aureus. Infect Immun 67 : 3667–3669. 10377157

55. Pfortner H, Burian MS, Michalik S, Depke M, Hildebrandt P et al. (2014) Activation of the alternative sigma factor SigB of Staphylococcus aureus following internalization by epithelial cells—an in vivo proteomics perspective. Int J Med Microbiol 304 : 177–187. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2013.11.014 24480029

56. Jarry TM, Cheung AL (2006) Staphylococcus aureus escapes more efficiently from the phagosome of a cystic fibrosis bronchial epithelial cell line than from its normal counterpart. Infect Immun 74 : 2568–2577. 16622192

57. Mestre MB, Fader CM, Sola C, Colombo MI (2010) Alpha-hemolysin is required for the activation of the autophagic pathway in Staphylococcus aureus-infected cells. Autophagy 6 : 110–125. 20110774

58. Schnaith A, Kashkar H, Leggio SA, Addicks K, Kronke M et al. (2007) Staphylococcus aureus subvert autophagy for induction of caspase-independent host cell death. J Biol Chem 282 : 2695–2706. 17135247

59. Mitchell G, Seguin DL, Asselin AE, Deziel E, Cantin AM et al. (2010) Staphylococcus aureus sigma B-dependent emergence of small-colony variants and biofilm production following exposure to Pseudomonas aeruginosa 4-hydroxy-2-heptylquinoline-N-oxide. BMC Microbiol 10 : 33. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-10-33 20113519

60. Moisan H, Brouillette E, Jacob CL, Langlois-Begin P, Michaud S et al. (2006) Transcription of virulence factors in Staphylococcus aureus small-colony variants isolated from cystic fibrosis patients is influenced by SigB. J Bacteriol 188 : 64–76. 16352822

61. Mitchell G, Fugere A, Pepin GK, Brouillette E, Frost EH et al. (2013) SigB is a dominant regulator of virulence in Staphylococcus aureus small-colony variants. PLoS ONE 8: e65018. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065018 23705029

62. Boles BR, Horswill AR (2008) Agr-mediated dispersal of Staphylococcus aureus biofilms. PLoS Pathog 4: e1000052. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000052 18437240

63. Grundmeier M, Tuchscherr L, Brück M, Viemann D, Roth J et al. (2010) Staphylococcal strains vary greatly in their ability to induce an inflammatory response in endothelial cells. J Infect Dis 201 : 871–880. doi: 10.1086/651023 20132035

64. Donegan NP, Cheung AL (2009) Regulation of the mazEF toxin-antitoxin module in Staphylococcus aureus and its impact on sigB expression. J Bacteriol 191 : 2795–2805. doi: 10.1128/JB.01713-08 19181798

65. Pane-Farre J, Jonas B, Forstner K, Engelmann S, Hecker M (2006) The sigmaB regulon in Staphylococcus aureus and its regulation. Int J Med Microbiol 296 : 237–258. 16644280

66. Bremell T, Abdelnour A, Tarkowski A (1992) Histopathological and serological progression of experimental Staphylococcus aureus arthritis. Infect Immun 60 : 2976–2985. 1612762

67. Vandenesch F, Kornblum J, Novick RP (1991) A temporal signal, independent of agr, is required for hla but not spa transcription in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol 173 : 6313–20. 1717437

68. Kullik I, Giachino P, Fuchs T (1998) Deletion of the alternative sigma factor sigmaB in Staphylococcus aureus reveals its function as a global regulator of virulence genes. J Bacteriol 180 : 4814–20. 9733682

69. Cheung AL, Ying P (1994) Regulation of alpha - and beta-hemolysins by the sar locus of Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol 176 : 580–585. 7507919

70. Giachino P, Engelmann S, Bischoff M (2001) Sigma(B) activity depends on RsbU in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol 183 : 1843–1852. 11222581

71. Bradford MM (1976) A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem 72 : 248–254. 942051

72. Madigang MT (2010) Brock Biology of Microorganisms.

73. Cooper MS, Rabbitt EH, Goddard PE, Bartlett WA, Hewison M et al. (2002) Osteoblastic 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 activity increases with age and glucocorticoid exposure. J Bone Miner Res 17 : 979–986. 12054173

74. Jaffe EA, Nachman RL, Becker CG, Minick CR (1973) Culture of human endothelial cells derived from umbilical veins. Identification by morphologic and immunologic criteria. J Clin Invest 52 : 2745–56. 4355998

75. Mosser DM, Edwards JP (2008) Exploring the full spectrum of macrophage activation. Nat Rev Immunol 8 : 958–969. doi: 10.1038/nri2448 19029990

76. Grosz M, Kolter J, Paprotka K, Winkler AC, Schafer D et al. (2014) Cytoplasmic replication of Staphylococcus aureus upon phagosomal escape triggered by phenol-soluble modulin alpha. Cell Microbiol 16 : 451–465. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12233 24164701

77. Grundling A, Schneewind O (2007) Synthesis of glycerol phosphate lipoteichoic acid in Staphylococcus aureus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104 : 8478–8483. 17483484

78. Haslinger B, Strangfeld K, Peters G, Schulze-Osthoff K, Sinha B (2003) Staphylococcus aureus alpha-toxin induces apoptosis in peripheral blood mononuclear cells: role of endogenous tumour necrosis factor-alpha and the mitochondrial death pathway. Cell Microbiol 5 : 729–41. 12969378

79. Löffler B, Hussain M, Grundmeier M, Bruck M, Holzinger D et al. (2010) Staphylococcus aureus panton-valentine leukocidin is a very potent cytotoxic factor for human neutrophils. PLoS Pathog 6: e1000715. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000715 20072612

80. Larzabal M, Mercado EC, Vilte DA, Salazar-Gonzalez H, Cataldi A et al. (2010) Designed coiled-coil peptides inhibit the type three secretion system of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. PLoS ONE 5: e9046. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009046 20140230

81. Garzoni C, Francois P, Huyghe A, Couzinet S, Tapparel C et al. (2007) A global view of Staphylococcus aureus whole genome expression upon internalization in human epithelial cells. BMC Genomics 8 : 171. 17570841

82. Hawkins P, Morton DB, Burman O, Dennison N, Honess P et al. (2011) A guide to defining and implementing protocols for the welfare assessment of laboratory animals: eleventh report of the BVAAWF/FRAME/RSPCA/UFAW Joint Working Group on Refinement. Lab Anim 45 : 1–13. doi: 10.1258/la.2010.010031 21123303

Štítky

Hygiena a epidemiológia Infekčné lekárstvo Laboratórium

Článek Relay of Herpes Simplex Virus between Langerhans Cells and Dermal Dendritic Cells in Human SkinČlánek Does the Arthropod Microbiota Impact the Establishment of Vector-Borne Diseases in Mammalian Hosts?Článek The Ebola Epidemic Crystallizes the Potential of Passive Antibody Therapy for Infectious DiseasesČlánek Hepatitis D Virus Infection of Mice Expressing Human Sodium Taurocholate Co-transporting PolypeptideČlánek A Redox Regulatory System Critical for Mycobacterial Survival in Macrophages and Biofilm Development

Článok vyšiel v časopisePLOS Pathogens

Najčítanejšie tento týždeň

2015 Číslo 4- Parazitičtí červi v terapii Crohnovy choroby a dalších zánětlivých autoimunitních onemocnění

- Očkování proti virové hemoragické horečce Ebola experimentální vakcínou rVSVDG-ZEBOV-GP

- Koronavirus hýbe světem: Víte jak se chránit a jak postupovat v případě podezření?

-

Všetky články tohto čísla

- Pathogens as Biological Weapons of Invasive Species

- Selection and Spread of Artemisinin-Resistant Alleles in Thailand Prior to the Global Artemisinin Resistance Containment Campaign

- Endopeptidase-Mediated Beta Lactam Tolerance

- Prospective Large-Scale Field Study Generates Predictive Model Identifying Major Contributors to Colony Losses

- Relay of Herpes Simplex Virus between Langerhans Cells and Dermal Dendritic Cells in Human Skin

- Structural Determinants of Phenotypic Diversity and Replication Rate of Human Prions

- Sigma Factor SigB Is Crucial to Mediate Adaptation during Chronic Infections

- EphrinA2 Receptor (EphA2) Is an Invasion and Intracellular Signaling Receptor for

- Toxin-Induced Necroptosis Is a Major Mechanism of Lung Damage

- Heterologous Expression in Remodeled . : A Platform for Monoaminergic Agonist Identification and Anthelmintic Screening

- Novel Disease Susceptibility Factors for Fungal Necrotrophic Pathogens in Arabidopsis

- Interleukin 21 Signaling in B Cells Is Required for Efficient Establishment of Murine Gammaherpesvirus Latency

- Phosphorylation at the Homotypic Interface Regulates Nucleoprotein Oligomerization and Assembly of the Influenza Virus Replication Machinery

- Human Papillomaviruses Activate and Recruit SMC1 Cohesin Proteins for the Differentiation-Dependent Life Cycle through Association with CTCF Insulators

- Ubiquitous Promoter-Localization of Essential Virulence Regulators in

- TGF-β Suppression of HBV RNA through AID-Dependent Recruitment of an RNA Exosome Complex

- The Immune Adaptor ADAP Regulates Reciprocal TGF-β1-Integrin Crosstalk to Protect from Influenza Virus Infection

- Antagonism of miR-328 Increases the Antimicrobial Function of Macrophages and Neutrophils and Rapid Clearance of Non-typeable (NTHi) from Infected Lung

- The Epigenetic Regulator G9a Mediates Tolerance to RNA Virus Infection in

- Does the Arthropod Microbiota Impact the Establishment of Vector-Borne Diseases in Mammalian Hosts?

- Hantaan Virus Infection Induces Both Th1 and ThGranzyme B+ Cell Immune Responses That Associated with Viral Control and Clinical Outcome in Humans

- Viral Inhibition of the Transporter Associated with Antigen Processing (TAP): A Striking Example of Functional Convergent Evolution

- Plasma Membrane Profiling Defines an Expanded Class of Cell Surface Proteins Selectively Targeted for Degradation by HCMV US2 in Cooperation with UL141

- Optineurin Regulates the Interferon Response in a Cell Cycle-Dependent Manner

- IFIT1 Differentially Interferes with Translation and Replication of Alphavirus Genomes and Promotes Induction of Type I Interferon

- The EBNA3 Family of Epstein-Barr Virus Nuclear Proteins Associates with the USP46/USP12 Deubiquitination Complexes to Regulate Lymphoblastoid Cell Line Growth

- Hepatitis C Virus RNA Replication Depends on Specific and -Acting Activities of Viral Nonstructural Proteins

- A Neuron-Specific Antiviral Mechanism Prevents Lethal Flaviviral Infection of Mosquitoes

- The Aspartate-Less Receiver (ALR) Domains: Distribution, Structure and Function

- Global Genome and Transcriptome Analyses of Epidemic Isolate 98-06 Uncover Novel Effectors and Pathogenicity-Related Genes, Revealing Gene Gain and Lose Dynamics in Genome Evolution

- The Ebola Epidemic Crystallizes the Potential of Passive Antibody Therapy for Infectious Diseases

- Ebola Virus Entry: A Curious and Complex Series of Events

- Conserved Spirosomes Suggest a Single Type of Transformation Pilus in Competence

- Spatial Structure, Transmission Modes and the Evolution of Viral Exploitation Strategies

- Bacterial Cooperation Causes Systematic Errors in Pathogen Risk Assessment due to the Failure of the Independent Action Hypothesis

- Transgenic Fatal Familial Insomnia Mice Indicate Prion Infectivity-Independent Mechanisms of Pathogenesis and Phenotypic Expression of Disease

- Cerebrospinal Fluid Cytokine Profiles Predict Risk of Early Mortality and Immune Reconstitution Inflammatory Syndrome in HIV-Associated Cryptococcal Meningitis

- Utilize Host Actin for Efficient Maternal Transmission in

- Borna Disease Virus Phosphoprotein Impairs the Developmental Program Controlling Neurogenesis and Reduces Human GABAergic Neurogenesis

- An Effector Peptide Family Required for Toll-Mediated Immunity

- Hepatitis D Virus Infection of Mice Expressing Human Sodium Taurocholate Co-transporting Polypeptide

- A Redox Regulatory System Critical for Mycobacterial Survival in Macrophages and Biofilm Development

- Quadruple Quorum-Sensing Inputs Control Virulence and Maintain System Robustness

- Leukocyte-Derived IFN-α/β and Epithelial IFN-λ Constitute a Compartmentalized Mucosal Defense System that Restricts Enteric Virus Infections

- A Strategy for O-Glycoproteomics of Enveloped Viruses—the O-Glycoproteome of Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1

- Macrocyclic Lactones Differ in Interaction with Recombinant P-Glycoprotein 9 of the Parasitic Nematode and Ketoconazole in a Yeast Growth Assay

- Neofunctionalization of the α1,2fucosyltransferase Paralogue in Leporids Contributes to Glycan Polymorphism and Resistance to Rabbit Hemorrhagic Disease Virus

- The Extracytoplasmic Linker Peptide of the Sensor Protein SaeS Tunes the Kinase Activity Required for Staphylococcal Virulence in Response to Host Signals

- Murine CMV-Induced Hearing Loss Is Associated with Inner Ear Inflammation and Loss of Spiral Ganglia Neurons

- Dual miRNA Targeting Restricts Host Range and Attenuates Neurovirulence of Flaviviruses

- GATA-Dependent Glutaminolysis Drives Appressorium Formation in by Suppressing TOR Inhibition of cAMP/PKA Signaling

- Role of Hypoxia Inducible Factor-1α (HIF-1α) in Innate Defense against Uropathogenic Infection

- Genetic Analysis Using an Isogenic Mating Pair of Identifies Azole Resistance Genes and Lack of Locus’s Role in Virulence

- A Temporal Gate for Viral Enhancers to Co-opt Toll-Like-Receptor Transcriptional Activation Pathways upon Acute Infection

- Neutrophil Recruitment to Lymph Nodes Limits Local Humoral Response to

- PLOS Pathogens

- Archív čísel

- Aktuálne číslo

- Informácie o časopise

Najčítanejšie v tomto čísle- Toxin-Induced Necroptosis Is a Major Mechanism of Lung Damage

- Transgenic Fatal Familial Insomnia Mice Indicate Prion Infectivity-Independent Mechanisms of Pathogenesis and Phenotypic Expression of Disease

- Role of Hypoxia Inducible Factor-1α (HIF-1α) in Innate Defense against Uropathogenic Infection