-

Články

- Časopisy

- Kurzy

- Témy

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Lifespan Extension by Methionine Restriction Requires Autophagy-Dependent Vacuolar Acidification

Health - or lifespan-prolonging regimes would be beneficial at both the individual and the social level. Nevertheless, up to date only very few experimental settings have been proven to promote longevity in mammals. Among them is the reduction of food intake (caloric restriction) or the pharmacological administration of caloric restriction mimetics like rapamycin. The latter one, however, is accompanied by not yet fully estimated and undesirable side effects. In contrast, the limitation of one specific amino acid, namely methionine, which has also been demonstrated to elongate the lifespan of mammals, has the advantage of being a well applicable regime. Therefore, understanding the underlying mechanism of the anti-aging effects of methionine restriction is of crucial importance. With the help of the model organism yeast, we show that limitation in methionine drastically enhances autophagy, a cellular process of self-digestion that is also switched on during caloric restriction. Moreover, we demonstrate that this occurs in causal conjunction with an efficient pH decrease in the organelle responsible for the digestive capacity of the cell (the vacuole). Finally, we prove that autophagy-dependent vacuolar acidification is necessary for methionine restriction-mediated lifespan extension.

Published in the journal: Lifespan Extension by Methionine Restriction Requires Autophagy-Dependent Vacuolar Acidification. PLoS Genet 10(5): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004347

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1004347Summary

Health - or lifespan-prolonging regimes would be beneficial at both the individual and the social level. Nevertheless, up to date only very few experimental settings have been proven to promote longevity in mammals. Among them is the reduction of food intake (caloric restriction) or the pharmacological administration of caloric restriction mimetics like rapamycin. The latter one, however, is accompanied by not yet fully estimated and undesirable side effects. In contrast, the limitation of one specific amino acid, namely methionine, which has also been demonstrated to elongate the lifespan of mammals, has the advantage of being a well applicable regime. Therefore, understanding the underlying mechanism of the anti-aging effects of methionine restriction is of crucial importance. With the help of the model organism yeast, we show that limitation in methionine drastically enhances autophagy, a cellular process of self-digestion that is also switched on during caloric restriction. Moreover, we demonstrate that this occurs in causal conjunction with an efficient pH decrease in the organelle responsible for the digestive capacity of the cell (the vacuole). Finally, we prove that autophagy-dependent vacuolar acidification is necessary for methionine restriction-mediated lifespan extension.

Introduction

Methionine restriction (MetR) has been long known to enhance lifespan in various organisms, including mammals [1], [2]. Nevertheless, the mechanisms underlying this phenomenon are poorly understood. Previous studies have mainly focused on MetR-induced alterations of the function and composition of respiratory chain complexes in mitochondria, although no clear cause-effect relationship between these effects and the beneficial impact on longevity could be established [3]–[5].

Given that MetR represents a regime that limits availability of an amino acid, we wondered if the resulting longevity effect might include the involvement of autophagy [6], which is known to play a crucial role in cells that are stressed by damage or limited nutrient supply [7]. Only recently, autophagy has been shown to play an important role for lifespan extension by treatment with spermidine, rapamycin, or resveratrol, as well as by depletion of the p53 ortholog from Caenorhabditis elegans, the inhibition of IGF signaling, and the overexpression of sirtuin [8]–[12]. The autophagic process depends on the vacuolar proteolytic activity, which is determined by vacuolar acidification [13], [14]. Based on these premises, we decided to analyze whether macroautophagy (hereafter referred to as autophagy) is also induced under conditions of MetR and if autophagy induction contributes to MetR-induced lifespan extension. In addition, we analyzed the extent of vacuolar acidification, which has been recently shown to be crucial for lifespan extension in replicatively aging cells [15]. To tackle these questions, we decided to use baker's yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) as a model system, since (i) it constitutes a well-established (chronological) aging model [16]; (ii) autophagy was discovered and largely uncovered in this model [17]–[19]; and (iii) MetR can be reliably controlled by virtue of media supplementation and the deletion of genes involved in its biosynthesis [20].

Here, we report that MetR causes an increase in chronological lifespan (CLS) that depends on the enhanced vacuole acidification that follows autophagy stimulation.

Results

Methionine limitation causes longevity during yeast chronological aging

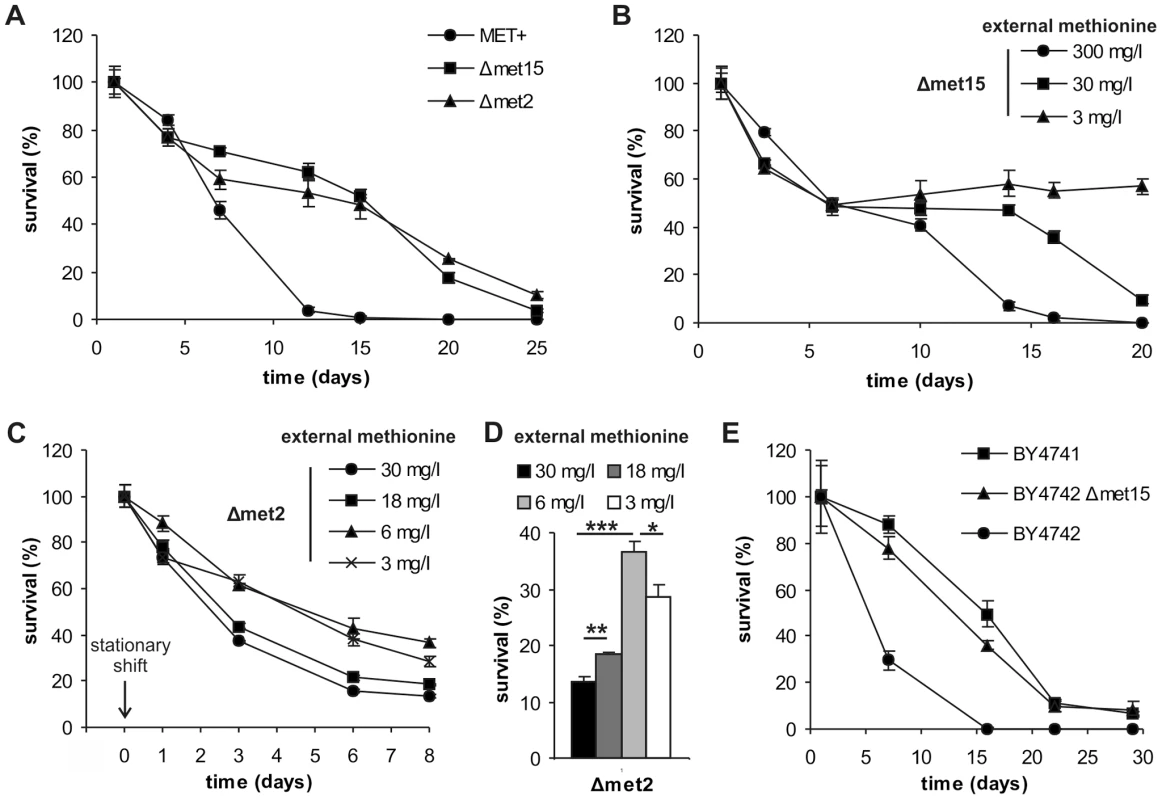

To determine whether MetR influences yeast CLS, three different strains were used: (i) a MET+ strain that is fully competent in synthesizing methionine, (ii) a knockout strain deleted in met15 that suffers only a moderate defect in methionine biosynthesis due to an intact salvage pathway mediated via O-acetyl-homoserine (the reaction product of Met2p), and (iii) a met2 deletion strain fully devoid of a de novo methionine synthesis and hence strictly dependent on externally supplied methionine [20]. These three strains are otherwise isogenic (Table S1). The methionine-prototroph strain (MET+) exhibited a rather short CLS of about 10 to 15 days, while the two methionine-auxotroph strains with limited (Δmet15) and no (Δmet2) endogenous methionine biosynthesis displayed enhanced lifespans of up to 25 days (Figure 1A). Of note, these chronological aging experiments were performed in synthetic complete medium supplemented with 30 mg/l methionine. Using this medium, all three strains showed equivalent cell counts during aging experiments (Figure S1A) and cell cycle arrest in G0/G1 was comparable (Figure S1B), therefore excluding potential artifacts secondary to differential growth rates and nutrient consumption. Furthermore, chronological aging experiments of MET+, Δmet15 and Δmet2 revealed only marginal differences in external media pH (Figure S1C), thus showing that external pH effects do not play a major role in this scenario [21]. Accordingly, it has been recently shown that lifespan-enhancing conditions do not necessarily correlate with changes in pH [22].

Fig. 1. Methionine determines yeast chronological lifespan.

(A) Chronological aging of methionine prototroph (MET+), semi-auxotroph (Δmet15) and auxotroph (Δmet2) isogenic yeast strains in SCD media supplemented with all amino acids (aa). Cell survival was estimated as colony formation of 500 cells plated at given time points, normalized to cell survival on day one (n = 4). (B) Chronological aging of Δmet15 strain, in SCD media supplemented with all aa except for methionine which was added at given concentrations. Cell survival of 500 cells plated at given time points, normalized to cell survival on day one (n = 4). (C) MET2 deletion strain (Δmet2) was grown to stationary phase in SCD (supplemented with all aa) and shifted to SCD media with different methionine concentrations. Cell survival of 500 cells plated at given time points, normalized to cell survival before the shift (n = 4). (D) Day 8 from experiment shown in C (n = 4). (E) Chronological aging of EUROSCARF BY4741 (also used above as Δmet15 reference strain) and mating type α wild type strain BY4742, as well as a methionine semi-auxotrophic variant thereof (BY4742 Δmet15), in SCD media supplemented with all aa. Cell survival of 500 cells plated at given time points, normalized to cell survival on day one (n = 3). See also Figure S1. We next determined the influence of external methionine availability on the MET+, Δmet15, and Δmet2 strains by using media supplemented with varying methionine concentrations. Higher levels of supplemented methionine led to decreased survival in Δmet15 and Δmet2 strains (Figure 1B and Figure S1D) whereas a reduction of methionine led to improved longevity - especially of long-term survival - of the semi-auxotrophic strain (Δmet15, Figure 1B, cell-counts Figure S1E), but not of the prototrophic strain (MET+) (Figure S1F, cell-counts Figure S1G). Of note, lower amounts of cysteine (a downstream product of methionine biosynthesis) did not increase CLS of Δmet15 whereas high amounts shorten CLS, potentially via formation of methionine by transsulfuration (Figure S1H) [20]. Also note that reduced methionine levels were not used in the case of the auxotrophic Δmet2 strain because cell counts, grown in the presence of 3 mg/l, of this strain are ten times lower compared to 30 mg/l standard conditions (Figure S1I). Thus, to verify effects of low levels of methionine on the fully auxotrophic Δmet2 strain during chronological aging, cells were grown to stationary phase (24 hours) in media with excess methionine (30 mg/l) to support normal growth, and then transferred to media with lower methionine concentrations (Figure 1C and D). Δmet2 cell cultures transferred to media with high methionine concentrations exhibited accelerated aging, while lowering methionine concentrations increased longevity. Optimal cell survival was reached with around 6 mg/l externally supplied methionine (Figure 1C and D). Thus MetR during chronological aging can only be achieved by combining both, the deletion of specific genes involved in its biosynthesis and external methionine supplementation. Moreover, MetR resulted in reduced phosphatidylserine externalization (a typical sign of apoptosis) and improved plasma membrane integrity (which is disrupted in necrosis), as determined by AnnexinV/PI-costaining (Figure S2A). The levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which are suspected mediators of cellular aging, were determined by monitoring the conversion of dihydroethidium (DHE) to fluorescent ethidium (Eth), as driven by superoxide anion radicals. ROS levels were clearly diminished in Δmet15 and Δmet2 strains (Figure S2B).

Intriguingly, one genetic difference (beside the functionality of their LYS2 gene-product and a different mating type) of the frequently used wild type strains of the EUROSCARF strain collection, BY4741 and BY4742, also affects their ability to produce methionine. The long-lived BY4741 strain harbors a deletion of MET15 (and was also used in the above described experiments) whereas the short-lived BY4742 strain is methionine-prototroph. Deletion of MET15 from BY4742 reestablished a long-lived phenotype in chronological aging experiments, indicating that the short life expectancy of this strain is indeed due to its ability to synthesize methionine (Figure 1E).

We conclude that the amount of methionine availability – as determined by de novo synthesis or external supply – dramatically influences the survival of chronologically aging yeast and protects against apoptosis/necrosis.

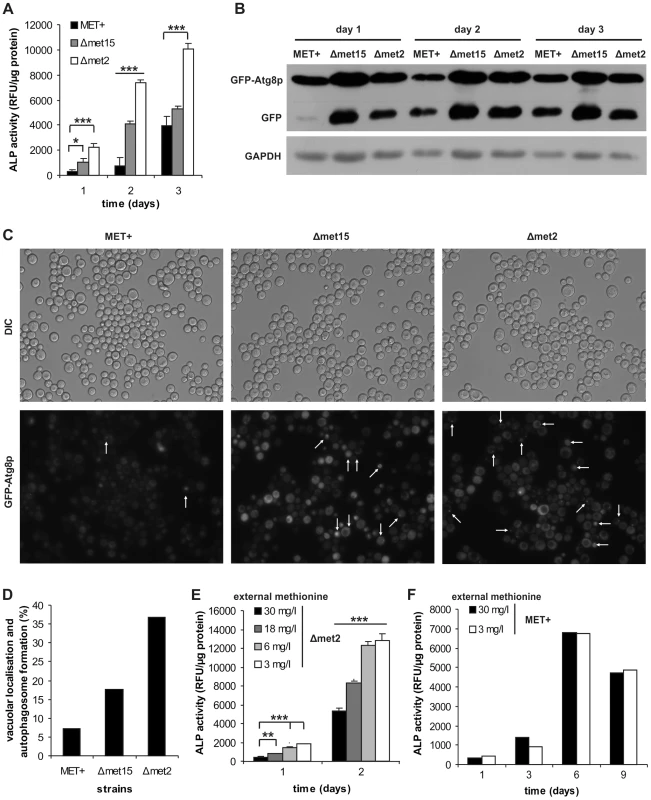

Autophagy is specifically induced upon methionine restriction

Since autophagy might be one of the major pathways responsible for lifespan extension in various organisms and under diverse circumstances [10], [23] we determined the rate of autophagy within the cell cultures. During the first days of chronological aging, alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity (which measures the activity of cytosolic ALP which is delivered to the vacuole exclusively via autophagy) was significantly higher in Δmet15 and Δmet2 strains compared to the MET+ strain (Figure 2A). Accordingly, vacuolar processing of GFP-tagged Atg8p, which takes place under autophagic conditions for recycling of the protein, was elevated upon MetR, as visualized by immunoblotting (Figure 2B). Furthermore, the localization of GFP-tagged Atg8p, a protein essential for the autophagic process, which is normally evenly distributed in the cytoplasm (see MET+ strain), showed punctuate and/or vacuolar localization in Δmet15 and Δmet2 strains during chronological aging (shown for day 2 in Figure 2C and D). This reflects enhanced autophagosome formation and Atg8p-delivery to the vacuole. Of note, differences in the number of puncta per cell compared to the number of positive vacuoles per cell possibly reflect dynamics of this process and are subject to changes over time. To exclude effects of distinct Atg8p levels deriving from possible differences in synthesis capabilities of the different strain backgrounds, we performed overexpression studies of Atg8p in MET+. No differences in CLS were observed (Figure S3A). Next, we determined the autophagic flux (ALP activity) under different levels of MetR by transferring stationary Δmet2 cell cultures grown in excess of methionine to media supplemented with varying methionine concentrations that showed beneficial effects on longevity (see above and Figure 1C and D). A clear inverse correlation of methionine concentration and autophagy level was visible, reaching a nearly ten-fold difference in early onset of autophagy between a high methionine concentration (30 mg/l) and cells exposed to low concentrations (3 to 6 mg/l) of methionine (Figure 2E). In addition, the MET+ strain showed no altered ALP activity when grown in the presence of 3 mg/l methionine (Figure 2F), as opposed to the met15 deletion strain where ALP activity was strongly up-regulated (Figure S3B). Accordingly, the Δmet2 strain grown in the presence of high levels of external methionine showed decreased autophagy (Figure S3C). We conclude that methionine restriction specifically enhances autophagy during yeast chronological aging.

Fig. 2. MetR specifically regulates induction of autophagy.

MET+, Δmet15 and Δmet2 strains from chronological aging experiments were analyzed for vacuolar ALP activity (with a fluorescent plate reader) (A) (n = 6), and GFP-Atg8p processing (by Western-blot analysis) (B). (C) GFP-Atg8p localization was determined by using fluorescent microscopy (white arrows indicate vacuolar localization or autophagosome formation) and statistical analysis thereof (330–600 cells of each GFP-Atg8p expressing strain were evaluated from two independent samples) (D). (E) MET2 deletion strain (Δmet2) was grown to stationary phase in SCD (supplemented with all aa) and shifted to SCD media with given methionine concentrations. Autophagy was measured by means of ALP activity with a fluorescent plate reader (Tecan, Genios Pro) (n = 6). (F) ALP assays of chronological aging of MET+ strain, in SCD media supplemented with all aa except for methionine which was added at given concentrations (n = 2). See also Figure S3. Autophagy is essential for methionine restriction-induced longevity

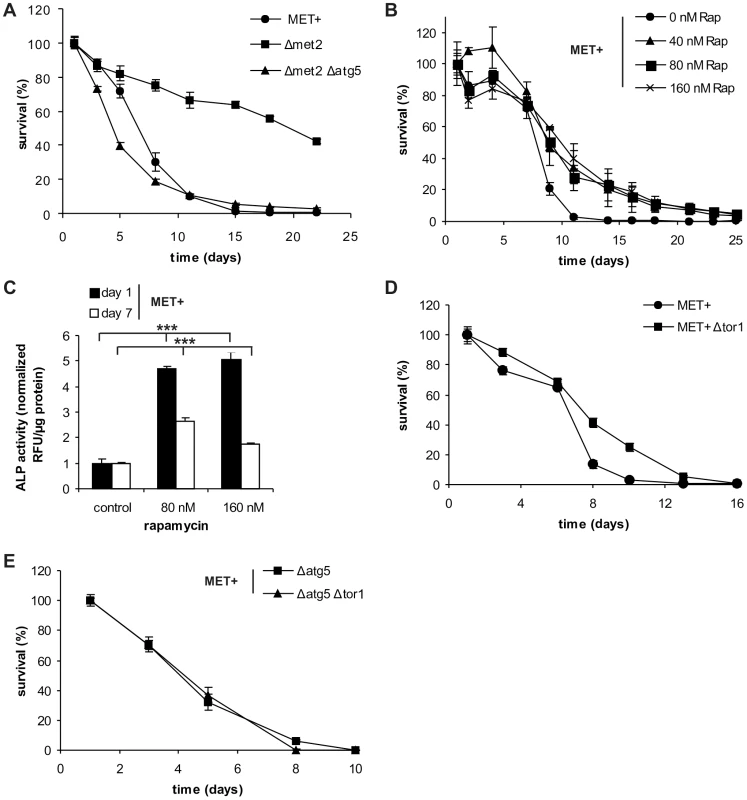

To verify whether autophagy truly impacts rather than only correlating with lifespan extension upon MetR, we subjected several strains harboring single deletions of genes necessary for MetR-triggered autophagy. Deletion of ATG5, ATG7 or ATG8, abolished the gain in longevity that was normally conferred by MetR. In both, the Δmet15 and the Δmet2 strains, lifespan was drastically shortened upon ATG gene deletions reaching comparable or even lower survival levels than those of the corresponding MET+ strain (Figure 3A and S4A, B). Of note, an additional RAS2 deletion, a well-established longevity-mediating mutation, in an autophagy-deficient Δmet2 strain (Δmet2 Δatg5) led to increased longevity, clearly indicating that autophagy-deficient strains are not per se unable to survive longer but that other (non-autophagic) pro-survival mechanisms are functional (Fig. S4C). Importantly, survival of the MET+ strain deleted for ATG5, ATG7 or ATG8, did not alter CLS during the first three days. Only after day 3, when autophagy started to increase (Figure 2A and B) and thus seemed to become a physiological need, CLS was shortened (Figure S4D).

Fig. 3. Autophagy is crucial for MetR-mediated longevity.

(A) Chronological aging of MET2 deletion strains carrying an additional gene deletion (Δatg5) and MET+ strain in SCD media supplemented with all aa. Cell survival of 500 cells plated at given time points, normalized to cell survival on day one (n = 6). (B) Chronological aging of MET+ strain treated with indicated amounts of rapamycin (Rap). Cell survival of 500 cells plated at given time points, normalized to cell survival on day one (n = 3; p***). Autophagy was measured by means of ALP activity with a fluorescent plate reader (Tecan, Genios Pro) and normalized to untreated controls at indicated time points (also compare to Figure 4E) (C) (n = 4). (D) Chronological aging of MET+ strain deleted for TOR1. Cell survival of 500 cells plated at given time points, normalized to cell survival on day one (n = 6; p***). (E) Chronological aging of the MET+ strain deleted for TOR1 and ATG5 or ATG5 alone. Cell survival of 500 cells plated at given time points, normalized to cell survival on day one (n = 4–6). See also Figure S4. Next, we determined whether rapamycin, an established pharmacological inhibitor of TOR and inducer of autophagy, could enhance lifespan of the MET+ strain. Rapamycin treatment indeed extended the longevity of the MET+ strain (Figure 3B). In accordance, the autophagy rate under these conditions was strongly induced (2 to 5 times) as measured via ALP activity (Figure 3C). To minimize its effects on growth behavior, rapamycin was added during mid-log phase (8 hours after inoculation of the main culture). Therefore, the positive effect on chronological survival is neither mediated by possible growth-delays (Figure S4E) [8] nor by an enhancement of respiration in the logarithmic growth phase (Figure S4F) [24]. Similar to the pharmacologically mediated inhibition of the TOR pathway (by rapamycin), genetic ablation of TOR1, the initiator-kinase of the autophagy-repressive TOR pathway, resulted in increased CLS of MET+ cells (Figure 3D). The additional deletion of ATG genes essential for autophagy (ATG5, ATG7, or ATG8) prevented the positive effects of TOR1 deletion in the methionine prototrophic strain (Figure 3E and Figure S4G and H), as was already shown for rapamycin mediated lonegvity [8]. We conclude that autophagy is crucial for MetR-induced longevity.

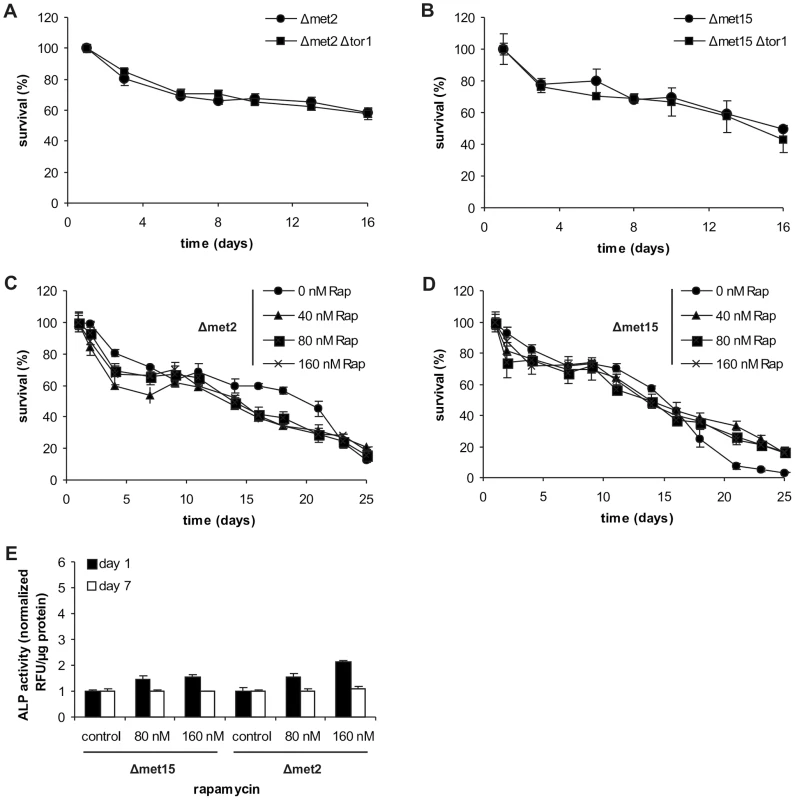

MetR-induced autophagy is epistatic to TOR inhibition

Because the TOR pathway is one of the major sensors for (external) amino acid availability, we asked whether lifespan extension under MetR conditions could be further enhanced by TOR inhibition. For this purpose, we deleted TOR1 in both the methionine-auxotrophic (Δmet2) and the semi-auxotrophic strains (Δmet15). Genetic ablation of the TOR pathway had no positive influence on survival (Figure 4A and B). This irresponsiveness seems to be independent from ROS generation since addition of low doses of glutathione did not affect CLS of Δmet2 and Δmet15 strains (Figure S5A and B). Intriguingly, external starvation for methionine in the Δmet2Δtor1 strain led to a small increase of autophagy on day 1, which became more pronounced with ongoing age (Figure S5C). This possibly shows that initial autophagy induction upon MetR is strongly dependent on TOR1 whereas its maintenance might be additionally supported by TOR1-independent mechanism(s). Pharmacological inhibition of the TOR pathway (via rapamycin) under the very same conditions as described for the MET+ strain also failed to increase longevity of the Δmet2 strain and had only rather small positive effects on the Δmet15 strain (Figure 4C and D). Of note, a stronger increase in cell count after day 1 was observed for all strains treated with rapamycin, irrespective of its impact on CLS (Figure S4E and S5D, E). Moreover, rapamycin treatment only marginally increased autophagy rates at day 1, and had no effects at day 7 (measured by means of ALP activity) during Δmet15 and Δmet2 chronological aging (Figure 4E). This was presumably the case because autophagy was already strongly stimulated. In contrast, rapamycin enhanced autophagy rates in the methionine-prototroph strain (MET+) to factors of up to 5, on day 1, and 2 to 3, on day 7 (see above and compare Figure 3C and 4E). We conclude that TOR inhibition and MetR are, at least partly, part of the same anti-aging pathway.

Fig. 4. MetR is epistatic to other longevity treatments involving TOR1 inhibition.

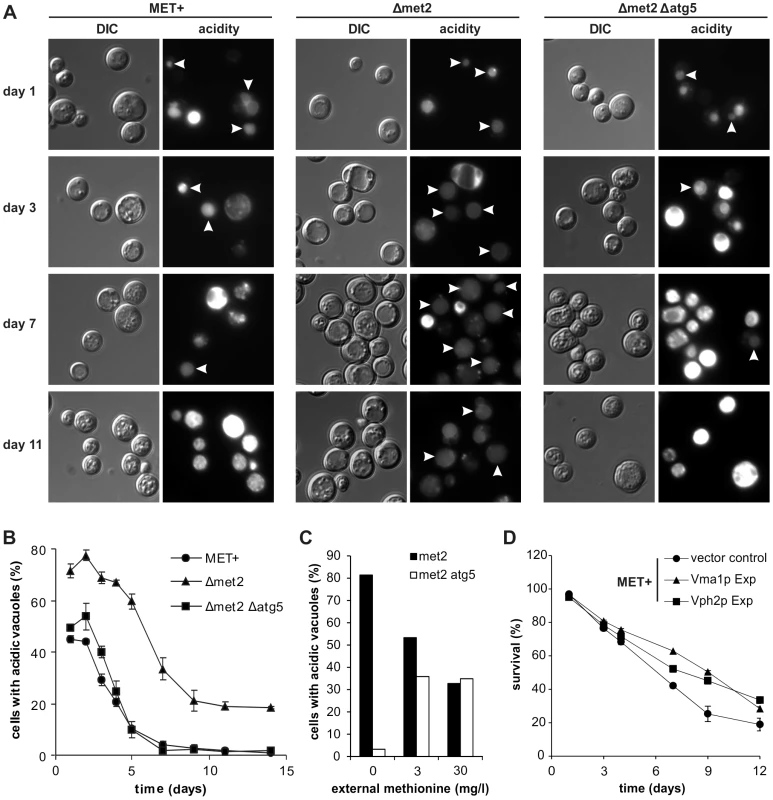

(A and B) Chronological aging of MET2 and MET15 deletion strains deleted for TOR1. Cell survival of 500 cells plated at given time points, normalized to cell survival on day one (n = 6). Chronological aging of MET2 (C) and MET15 (D) deletion strains treated with indicated amounts of rapamycin (Rap). Cell survival of 500 cells plated at given time points, normalized to cell survival on day one (n = 3). Autophagy was measured by means of ALP activity with a fluorescent plate reader (Tecan, Genios Pro) and normalized to untreated controls at indicated time points (also compare to Figure 3C) (E) (n = 4). See also Figure S5. MetR increases the number of cells with acidic vacuoles in an autophagy-dependent manner

The downstream target of autophagy is the vacuole. Thus, we mused if MetR-induced autophagy could enhance the degree of acidic vacuoles within the cell population. For this purpose, we stained chronologically aged MET+ or Δmet2 cells with quinacrine, the most widely used and highly specific stain for acidic cell compartments and counted for cells where only the vacuole was stained. The Δmet2 strain showed a 20% increase in cells harboring acidic vacuoles during chronological aging compared to the MET+ strain (Figure 5A and B). This increase was autophagy-dependent since it was completely abolished in a Δmet2 strain lacking ATG5 and thus autophagy-deficient (Figure 5A and B). Of note, cells showing a very bright quinacrine staining (older cells from MET+ and Δmet2/Δatg5, Figure 5A) represent cells with acidic cytoplasm, which harbor almost no intact vacuoles as demonstrated with quinacrine-stained cells expressing a chromosomal mCherry-tagged version of the vacuolar membrane-located Vph1p (Figure S6A). To further show a direct regulation of vacuolar acidity upon MetR, through autophagy, we shifted Δmet2 or Δmet2/Δatg5 cells to media with different methionine concentrations. The amount of cells with only acidic vacuoles was strictly dependent on the amount of supplemented methionine: ∼80% when shifted to media lacking methionine, ∼55% on 3 mg/l, and ∼35% on 30 mg/l methionine (Figure 5C). This dependency was blocked by an additional ATG5 deletion, which causally links vacuolar acidification to MetR-induced autophagy (Figure 5C). Moreover, the MET+ strain grown in the presence of rapamycin, showed an increased proportion of cells harboring acidic vacuoles during aging (Figure S6B), in line with the beneficial effects of this pharmacological intervention on survival and increased autophagy (Figure 3B and C). Of note, starting at day 3 we could observe that the MET+ strain showed distinctly more vacuolar cargo compared to Δmet2, which is probably due to limited clearance. We conclude that autophagy is sufficient to significantly enhance the proportion of cells harboring acidic vacuoles during yeast chronological aging.

Fig. 5. MetR enhancement of vacuolar acidification is autophagy-dependent and necessary for longevity.

Fluorescent microscopy of acidic vacuoles during chronological aging of MET+, Δmet2, and Δmet2/Δatg5 strains, by means of quinacrine accumulation and statistical analysis thereof. (>1000 cells of each strain from 3 to 5 independent samples at each time point were evaluated. Only cells with acidic vacuoles without an additionally stained cytoplasm were counted as positive, resulting in cell counts that represent cells which have a clearly intact pH-homeostasis. Positively counted cells are indicated by white arrowheads) (A and B). (C) Statistical analysis of fluorescent microscopy of acidic vacuoles by means of quinacrine accumulation. Strains Δmet2 and Δmet2/Δatg5 were grown to stationary phase under excess of methionine and shifted to media with the indicated amounts of methionine (>500 cells from each strain from 2 independent samples) and assayed for quinacrine accumulation after ∼20 hours (D) Chronological aging of the MET+ strain overexpressing Vma1p or Vph2p. Cell death was measured via propidium iodide staining of cells that have lost integrity and subsequent flow cytometry analysis (BD LSRFortessa) (n = 6 to 8). See also Figure S6. Blockage of vacuole acidification largely ameliorates positive effects of MetR on longevity while overexpression of v-ATPase components increases longevity

Interestingly, an enhanced proportion of cells bearing an acidic vacuole has been recently shown to be crucial for improved replicative longevity by overexpressing VMA1 or VPH2 and thus increasing vacuolar acidity [15]. To explore whether such causal connection is also present between the enhancement of acidic vacuoles and the extended lifespan by MetR-induced autophagy, we overexpressed Vma1p, a part of the vacuolar ATPase (v-ATPase) or Vph2p, essential for v-ATPase assembly [25]–[27] in the MET+ strain. Overexpression of both proteins led to increased CLS (Figure 5D). Moreover a Δmet2 strain deleted for VPH2 showed diminished survival during chronological aging resembling more closely the MET+ strain (Figure S6C). It should be noted that a deletion leading to no detectable acidic vacuoles via quinacrine staining (Figure S6D), causes pleiotropic effects [28] and thus results must be interpreted cautiously. Still and supporting our knockout results, overexpression of Vph2p or Vma1p in the methionine-auxotrophic Δmet2 strain did not improve CLS (Figure S6E). These results support a model, in which MetR-induced autophagy regulates vacuolar acidity which in turn promotes longevity (Figure 6). This places MetR-induced autophagy at the hub of vacuolar acidification and its positive effects on chronological survival, which are at least partly responsible for the positive effects observed on longevity through MetR (starvation for methionine).

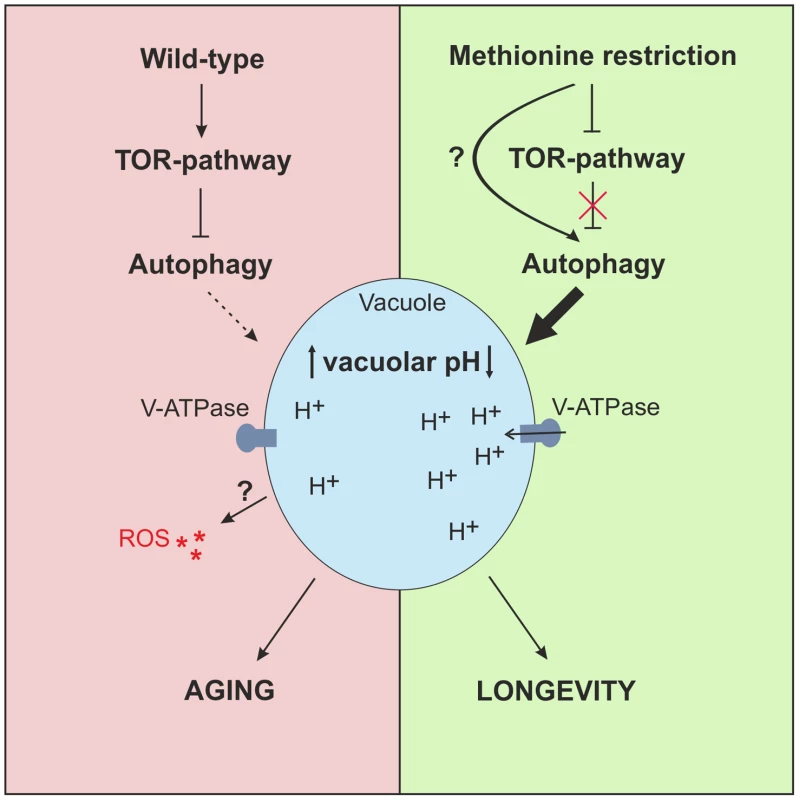

Fig. 6. Model of MetR-mediated longevity.

MetR specifically enhances autophagy, either by interfering upstream of TOR-pathway or presumably by impinging on (metabolic) pathways that potentially target autophagy directly, downstream of the TOR-pathway. MetR-specific vacuolar acidification is dependent on autophagy and elongates CLS. High levels of methionine inhibit autophagy induction during early phases of chronological aging, enhancing ROS and diminishing acidic vacuoles in a cell population, which leads to cell death. Discussion

Using S. cerevisiae, the key model organism in which autophagy was first functionally described and genetically dissected [17]–[19], we demonstrate that methionine restriction (MetR), unlike restriction in other amino acids such as leucine [6], [29], promotes clonogenic survival during chronological aging. MetR inhibits the ROS overproduction, as well as the aging-associated mortality by both apoptosis and necrosis. MetR shares analogies to limitations in elemental nutrients such as phosphor and sulfate, which induce a specific cell cycle arrest [30]. However, we could not find any signs of cell cycle blockade and our experiments were performed under conditions that fully supported growth to stationary phase in both methionine auxotrophic (Δmet2) and semi-auxotrophic (Δmet15) strains. Although there were no discernible cell cycle effects, MetR-induced lifespan extension correlated with enhanced autophagy, and the positive effect of MetR on longevity was lost when essential ATG genes were deleted. Accordingly, pharmacological or genetic inhibition of the TOR-pathway (and thus autophagy induction) enhanced CLS of a methionine-prototroph strain (MET+) but failed to do so in the methionine-auxotroph strains Δmet2 and Δmet15. This epistatic analysis fully validates the concept that the beneficial effects of MetR on longevity are mediated by autophagy.

Only recently, two new mechanisms for autophagy regulation were described: (i) a methionine-related one, involving the protein phosphatase 2a (PP2A), high levels of which were shown to down-regulate autophagy in dependence of methionine availability [31] and (ii) a methionine-independent mechanism, where high acetate levels block autophagy induction [32]. In our MetR setup, the first mechanism does not seem to play a major role since the MET+ strain lacking PPM1 (the methyltransferase of PP2A), did not lead to better chronological survival and deletions in PPH21 or PPH22 (catalytic subunits of the PP2A complex) had only small positive effects (Figure S7A). Instead, acetate levels in the media of the MET+ strain were about 80% higher compared to those of Δmet15 and Δmet2 strains on day 1, reaching comparable (Δmet2) or lower levels (Δmet15) on day 2 (Figure S7B) of chronological aging. Given the complex regulatory network PP2A is involved in and the metabolic and regulatory implications high acetate levels potentially lead to, contributions to autophagy induction are likely dependent on growth conditions and molecular fine-tuning. However, both pathways potentially influence the TOR pathway or its downstream targets thus supporting our epistasis analysis of MetR and TOR inhibition. Future work will be needed to decipher the specific contributions of these pathways/metabolites under different longevity-mediating regimens.

Altogether, methionine as an ubiquitous factor within cell metabolism may impact aging through several mechanisms that share or are independent from the herein described, for instance, a recent study suggests that methionine regulates homeostasis through modulation of tRNA thiolation and thus translation capacity [33].

Furthermore, we could clearly demonstrate that the proportion of cells displaying an acidic vacuole within a population is significantly enhanced via MetR inflicted either by genetic deletion of met2 and external methionine availability, or rapamycin treatment of MET+. Additionally, we show that this enhancement is strictly dependent on functional autophagy (as shown by an ATG5 deletion). In line, increasing v-ATPase activity (by overexpression of Vph2p or Vma1p), a process already shown to increase vacuolar acidity [15], is sufficient to increase CLS in a methionine-prototrophic strain. Conclusively, deletion of VPH2 and thus disruption of v-ATPase activity reverses the positive effects of MetR on CLS. Intriguingly, it has been recently demonstrated that an increase in vacuolar pH, specifically during early age, negatively influences the replicative lifespan of yeast [15]. In the same line, a recently published screen for chemical compounds extending CLS in Schizosaccharomyces pombe identified, among others, vacuolar acidification as a key process [34]. Additionally, Hughes and Gottschling showed that decreased vacuolar pH positively impacts mitochondrial function [15]. Interestingly, others have determined that autophagy is required to maintain respiration proficiency under caloric restriction conditions in galactose media [29], highlighting a protective role of autophagy, especially for mitochondrial function. In the frame of these observations, the decrease in ROS production during MetR may suggest a mechanistic structure that couples MetR-induced autophagy and vacuolar acidification to mitochondrial function.

In studies relating longevity to autophagy, doubts can be raised on the interpretation of the negative effects of genetic autophagy defects because the deletion of ATG genes may perturb cell survival per se [35]. However, we find that in our experimental setup, cells deleted for ATG genes, in fact, display normal growth rates and survival during the first days of chronological aging. Furthermore, we clearly demonstrate that an additional RAS2 deletion in an autophagy-deficient Δmet2 strain enhances the mutant's CLS. Nevertheless, the positive effects of a RAS2 deletion during chronological aging under MetR conditions seem to be limited since longevity is only marginally enhanced in a Δmet2 strain. This points towards the concept that autophagy is a process that significantly contributes to enhanced longevity upon RAS2 deletion.

Our work clarifies two further, thus far unexplained issues that are of great importance to researchers working on (yeast) aging: First, we demonstrate that the heterogeneity in CLS of the EUROSCARF wild-type strains BY4741 and BY4742 can be explained by strain-dependent differences in methionine biosynthesis. Second, we show that treatment with rapamycin or deletion of TOR1 almost only increases the longevity of strains that are methionine-prototrophic. Intriguingly, despite one study that could show enhanced CLS by tor1 deletion in BY4741 [36], previously published results on extension of CLS via TOR1 inhibition were performed in strains that are prototrophic for methionine [8], [24], [37]. We can also show that early phases of MetR-mediated autophagy are largely dependent on TOR1 or impact the same downstream targets. At the same time, there seem to be additional TOR1-independent mechanisms of MetR-induced autophagy later on during CLS, which will need to be addressed in future studies. Taken together, we show that autophagy-mediated vacuolar acidification is essential for the anti-aging effects of MetR, one of the rare lifespan-extending scenarios that is conserved across species.

Materials and Methods

Yeast strains and media

Experiments were carried out in strains using the EUROSCARF strain collection as basis and are listed in Table S1. In brief: BY4741 (MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0) was used as Δmet15 strain. MET+ was constructed by crossing BY4741 with BY4742 and tetrad selection for being methionine prototroph but otherwise isogenic to BY4741. Accordingly Δmet2 was generated by crossing BY4741 Δmet2::kanMX (EUROSCARF) with BY4742 and tetrad selection for tetra-type (all four spores are methionine auxotroph) and further selection for geneticin resistance (only conferred by Δmet2::kanMX). All other deletion strains and chromosomal GFP tagging in these backgrounds were carried out by classical homologous recombination using the pUG and pYM vector systems [38]–[40], and controlled by PCR. Transformation was done using the lithium acetate method [41]. Notably, at least two different clones were tested for any experiment with these newly transformed strains to rule out clonogenic variation of the observed effects. To generate strains with chromosomal mCherry tags at the C-terminus of the vacuolar membrane protein Vph1 plasmid pFA6a3mcherry-natNT2 or pFA6a3mcherry-hphNT1was used for PCR amplification. After transformation and selection, correct integration was tested via PCR and fluorescent microscopy. For overexpression studies of VPH2, VMA1, and ATG8 genes were amplified by PCR and inserted into the pESC-HIS vector (Stratagene). Resulting plasmids were verified by sequencing by eurofins/MWG, transformed via the lithium acetate method and subsequently expression was verified by western blot analysis.

All strains were grown on SC medium containing 0.17% yeast nitrogen base (BD Diagnostics; without ammonium sulfate and amino acids), 0.5% (NH4)2SO4, 30 mg/L of all amino acids (aa) (except 80 mg/liter histidine and 200 mg/liter leucine), 30 mg/L adenine, and 320 mg/L uracil with 2% glucose (SCD). All amino acids were purchased from Serva (research grade, ≥98.5%). For experiments with varying methionine or cysteine concentrations, methionine and cysteine were added at given concentrations. For overexpression with the pESC-HIS system strains were grown in the absence of histidine. When needed, glutathione was added at given concentrations at the time of inoculation. Survival plating was done on YPD agar plates (2% peptone, 1% yeast extract, 2% glucose, and 2% agar) and incubated for 2 to 3 days at 28°C.

Chronological aging, shift aging and overexpression aging

For chronological aging experiments cells were inoculated to 5×105 cells, or alternatively to an OD600 of 0.05, and grown for the indicated time period at 28°C in SC media. If not stated otherwise standard concentration of methionine (30 mg/l) was used throughout the experiments. Shift aging experiments with the Δmet2 strain were inoculated accordingly grown for 24 hours in excess of methionine (30 mg/l) and subsequently shifted to fresh SC media with indicated amounts of methionine. Of note For overexpression studies strains carrying VPH2, VMA1, or ATG8 on a pESC-HIS vector were grown in SCD for 6 hours and subsequently shifted into minimal media containing 0.5% galactose and 1.5% glucose, or 2% galactose (ATG8), for induction of expression. At the indicated time points cell survival was determined by clonogenictiy: Cell cultures were counted with a CASY cell counter (Schärfe System) and 500 cells were plated on YPD agar plates. Subsequently colony forming units were counted and values were normalized to survival at day one. Alternatively, cell death was measured via propidium iodide staining and subsequent flow cytometry analysis (BD FACSAria). Representative aging analyses are shown with at least three independent cultures aged at the same time. All aging analyses were performed at least twice in total with similar outcome.

Experiments involving treatment with rapamycin (LC laboratories) were performed as described above. To circumvent growth effects described in other publications rapamycin was added eight hours after inoculation and to lower amounts.

Tests for cell death markers, pH measurement, oxygen consumption, acidic vacuole staining, and cell cycle analysis

Dihydroethidium (DHE; working concentration: 2.5 µg/ml in PBS; ∼1×106 cells; incubation time 5 to 10 min at RT) staining (ROS production) and Annexin V/propidium iodide costaining (apoptosis/necrosis marker) were performed and quantified by using a fluorescent plate reader (Tecan, GeniusPRO) or by flow cytometry (BD FACSAria) as previously described [42]. 30,000 cells per sample were evaluated using BD FACSDiva software.

Measurement of growth media pH was performed at the indicated time points using a pH-Meter (Metrohm).

Oxygen consumption was determined eight hours after addition of rapamycin using an Oxygraph (Clark-type oxygen electrode connected to an ISO2 recorder; World Precision Instruments) and subsequent data processing with LabChart (ADInstruments).

Quinacrine (Sigma) was used to stain for acidic vacuoles following standard protocols [15]. Briefly, ∼2×106 cells were harvested, washed with YPD containing HEPES buffer (100 mM, pH7.6) and then collected and re-susupended in fresh YPD-HEPES containing 200 µM quinacrine After 10 min incubation at 30°C cells were put on ice and washed three times with ice-cold HEPES buffer containing 2% glucose an finally resuspended in the same buffer. All samples were kept on ice until they were viewed under the microscope within 1 hour since sample taking.

DNA content was measured as described previously [43]. Briefly, ∼1×107 cells were harvested, re-suspended in cold water and fixed with ice cold ethanol. After ∼16 h cells were harvested, re-suspended in sodium-citrate buffer (50 mM, pH7.4) and sonicated. After treatment with RNase and proteinase K, cells were stained overnight with propidium iodide (8 µg/ml), and analyzed by flow cytometry (BD LSRFortessa). 30,000 cells per sample were evaluated using BD FACSDiva software.

Microscopy

Microscopy of Quincarine stained cells as well as GFP-Atg8p expressing cells was performed with a Zeiss Axioskop microscope using a Zeiss Plan-Neofluar objective lens with 63× magnification and 1.25 numerical aperture or 40× magnification and 2.0 numerical aperture in oil (using Zeiss Immersol) at room temperature. Fluorescence microscopic sample images were taken with a Diagnostic Instruments camera (Model: SPOT 9.0 Monochrome-6), acquired and processed (coloring) using the Metamorph software (version 6.2r4, Universal Imaging Corp.) For creating a statistical analysis 330–600 cells of each GFP-Atg8p expressing strain were evaluated from two independent samples (Figure 3B). For statistical analysis of Quinacrine stained cells, >1000 cells of each strain from 3 to 5 independent samples at each time point were evaluated (Figure 5B and Figure S6B) or >500 cells of each condition from two independent samples (Figure 5C).

Alkaline phosphatase assay

Autophagy was monitored by alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity [44]. Strains were transformed with and selected for stable insertion of pTN9 HindIII fragment (confirmed by PCR). Briefly 1–5×10E7 cells were collected (and kept on ice from that moment on), washed, resuspended in assay buffer (Tris-HCl, 250 mM; pH = 9; 10 mM magnesium phosphate; 10 µM zinc sulfate), disrupted with glass beads, and centrifuged. Protein concentration was determined in the supernatant via a Bradford assay (BioRad) following standard protocols and subsequently 1 µg of total protein extract was subjected to the ALP assay. Extracts were incubated with α-naphtyl phosphate (55 mM) for 20 min at 30°C and stopped with 2 M glycine-NaOH (pH = 11). To correct for intrinsic (background) ALP activity, the corresponding strains without pTN9 were simultaneously processed and ALP activity was subtracted. Alternatively, strains were transformed with and selected for pCC5 (a plasmid carrying the cytoplasmic PHO8Δ60 [45]). Relative fluorescence units (RFU) were determined by using a fluorescence reader (Tecan, GeniusPRO) and applying the same manual gain throughout a series of measurements belonging together. For each transformed strain, two clones were tested.

Immunoblotting

Preparation of cell extracts and immunoblotting were performed as described [46]. Blots were probed with monoclonal mouse anti-GFP antibody (Roche, Cat.No:11814460001), rabbit polyclonal antibodies against glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (gift from Günther Daum) and the respective peroxidase-conjugated affinity-purified secondary antibody (Anti-Mouse IgG-Peroxidase antibody A9044 and Anti-Rabbit IgG-Peroxidase antibody A0545, Sigma). For detection the ECL system was used (Amersham).

Statistical analyses

Error bars (± SEM) are shown for independent experiments/samples. In cases when experiments were performed in parallel, a common overnight culture (ONC) for each strain was used. The number of independent data points (n) is indicated in the figure legends of the corresponding graphs. Significances were calculated using students t-test (one-tailed, unpaired). For aging experiments, a two-factor ANOVA with strain and time as independent factors was applied and corrected by the Bonferroni post hoc test. Significances: *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. OrentreichN, MatiasJR, DeFeliceA, ZimmermanJA (1993) Low methionine ingestion by rats extends life span. J Nutr 123 : 269–274 Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=8429371.

2. Lopez-TorresM, BarjaG (2008) Lowered methionine ingestion as responsible for the decrease in rodent mitochondrial oxidative stress in protein and dietary restriction possible implications for humans. Biochim Biophys Acta 1780 : 1337–1347 Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=18252204.

3. CaroP, GomezJ, SanchezI, NaudiA, AyalaV, et al. (2009) Forty percent methionine restriction decreases mitochondrial oxygen radical production and leak at complex I during forward electron flow and lowers oxidative damage to proteins and mitochondrial DNA in rat kidney and brain mitochondria. Rejuvenation Res 12 : 421–434 Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=20041736.

4. GomezJ, CaroP, SanchezI, NaudiA, JoveM, et al. (2009) Effect of methionine dietary supplementation on mitochondrial oxygen radical generation and oxidative DNA damage in rat liver and heart. J Bioenerg Biomembr 41 : 309–321 Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=19633937.

5. SanzA, CaroP, AyalaV, Portero-OtinM, PamplonaR, et al. (2006) Methionine restriction decreases mitochondrial oxygen radical generation and leak as well as oxidative damage to mitochondrial DNA and proteins. FASEB J 20 : 1064–1073 Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=16770005.

6. AlversAL, FishwickLK, WoodMS, HuD, ChungHS, et al. (2009) Autophagy and amino acid homeostasis are required for chronological longevity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Aging Cell 8 : 353–369 Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=19302372.

7. LevineB, KroemerG (2008) Autophagy in the pathogenesis of disease. Cell 132 : 27–42 Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=18191218.

8. AlversAL, WoodMS, HuD, KaywellAC, DunnWA, et al. (2009) Autophagy is required for extension of yeast chronological life span by rapamycin. Autophagy 5 : 847–849 Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19458476. Accessed 19 December 2012.

9. EisenbergT, KnauerH, SchauerA, BüttnerS, RuckenstuhlC, et al. (2009) Induction of autophagy by spermidine promotes longevity. Nature cell biology 11 : 1305–1314 Available: http://apps.webofknowledge.com/full_record.do?product = UA&search_mode = GeneralSearch&qid = 1&SID = N2ACH54LO89J@ODMOKC&page = 6&doc = 59. Accessed 5 November 2012.

10. MadeoF, TavernarakisN, KroemerG (2010) Can autophagy promote longevity? Nat Cell Biol 12 : 842–846 Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=20811357.

11. MorselliE, MaiuriMC, MarkakiM, MegalouE, PasparakiA, et al. (2010) Caloric restriction and resveratrol promote longevity through the Sirtuin-1-dependent induction of autophagy. Cell Death Dis 1: e10 Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=21364612.

12. TavernarakisN, PasparakiA, TasdemirE, MaiuriMC, KroemerG (2008) The effects of p53 on whole organism longevity are mediated by autophagy. Autophagy 4 : 870–873 Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=18728385.

13. TakeshigeK (1992) Autophagy in yeast demonstrated with proteinase-deficient mutants and conditions for its induction. The Journal of Cell Biology 119 : 301–311 Available: http://jcb.rupress.org/content/119/2/301.abstract. Accessed 5 June 2013.

14. NakamuraN, MatsuuraA, WadaY, OhsumiY (1997) Acidification of Vacuoles Is Required for Autophagic Degradation in the Yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Journal of Biochemistry 121 : 338–344 Available: http://jb.oxfordjournals.org/content/121/2/338.short. Accessed 5 June 2013.

15. HughesAL, GottschlingDE (2012) An early age increase in vacuolar pH limits mitochondrial function and lifespan in yeast. Nature 492 : 261–265 Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23172144. Accessed 5 June 2013.

16. LongoVD, GrallaEB, ValentineJS (1996) Superoxide dismutase activity is essential for stationary phase survival in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mitochondrial production of toxic oxygen species in vivo. The Journal of biological chemistry 271 : 12275–12280 Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8647826. Accessed 23 May 2013.

17. KlionskyDJ (2007) Autophagy: from phenomenology to molecular understanding in less than a decade. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 8 : 931–937 Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=17712358.

18. OhsumiY (2001) Molecular dissection of autophagy: two ubiquitin-like systems. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2 : 211–216 Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=11265251.

19. ThummM (2002) Hitchhikers guide to the vacuole-mechanisms of cargo sequestration in the Cvt and autophagic pathways. Mol Cell 10 : 1257–1258 Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=12503998.

20. ThomasD, Surdin-KerjanY (1997) Metabolism of sulfur amino acids in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 61 : 503–532 Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=9409150.

21. BurtnerCR, MurakamiCJ, KennedyBK, KaeberleinM (2009) A molecular mechanism of chronological aging in yeast. Cell Cycle 8 : 1256–1270 Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=19305133.

22. WuZ, LiuSQ, HuangD (2013) Dietary Restriction Depends on Nutrient Composition to Extend Chronological Lifespan in Budding Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. PloS one 8: e64448 Available: http://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0064448. Accessed 25 May 2013.

23. RubinszteinDC, MarinoG, KroemerG (2011) Autophagy and aging. Cell 146 : 682–695 Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=21884931.

24. PanY, SchroederEA, OcampoA, BarrientosA, ShadelGS (2011) Regulation of yeast chronological life span by TORC1 via adaptive mitochondrial ROS signaling. Cell Metab 13 : 668–678 Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=21641548.

25. KanePM, YamashiroCT, WolczykDF, NeffN, GoeblM, et al. (1990) Protein splicing converts the yeast TFP1 gene product to the 69-kD subunit of the vacuolar H(+)-adenosine triphosphatase. Science (New York, NY) 250 : 651–657 Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2146742. Accessed 13 March 2014.

26. HirataR, OhsumkY, NakanoA, KawasakiH, SuzukiK, et al. (1990) Molecular structure of a gene, VMA1, encoding the catalytic subunit of H(+)-translocating adenosine triphosphatase from vacuolar membranes of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. The Journal of biological chemistry 265 : 6726–6733 Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2139027. Accessed 13 March 2014.

27. JacksonDD (1997) VMA12 Encodes a Yeast Endoplasmic Reticulum Protein Required for Vacuolar H+-ATPase Assembly. Journal of Biological Chemistry 272 : 25928–25934 Available: http://www.jbc.org/content/272/41/25928.long. Accessed 29 August 2013.

28. KanePM (2007) The long physiological reach of the yeast vacuolar H+-ATPase. Journal of bioenergetics and biomembranes 39 : 415–421 Available: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=2901503&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. Accessed 27 January 2014.

29. ArisJP, AlversAL, FerraiuoloRA, FishwickLK, HanvivatpongA, et al. (2013) Autophagy and leucine promote chronological longevity and respiration proficiency during calorie restriction in yeast. Experimental gerontology 48 : 1107–19.

30. PettiAA, CrutchfieldCA, RabinowitzJD, BotsteinD (2011) Survival of starving yeast is correlated with oxidative stress response and nonrespiratory mitochondrial function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108: E1089–98.

31. SutterBM, WuX, LaxmanS, TuBP (2013) Methionine Inhibits Autophagy and Promotes Growth by Inducing the SAM-Responsive Methylation of PP2A. Cell 154 : 403–415 Available: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2013.06.041. Accessed 7 August 2013.

32. EisenbergT, SchroederS, AndryushkovaA, PendlT, KüttnerV, et al. (2014) Nucleocytosolic Depletion of the Energy Metabolite Acetyl-Coenzyme A Stimulates Autophagy and Prolongs Lifespan. Cell Metabolism 19 : 431–444 Available: http://www.cell.com/cell-metabolism/fulltext/S1550-4131(14)00066-7. Accessed 6 March 2014.

33. LaxmanS, SutterBM, WuX, KumarS, GuoX, et al. (2013) Sulfur amino acids regulate translational capacity and metabolic homeostasis through modulation of tRNA thiolation. Cell 154 : 416–429 Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23870129. Accessed 29 January 2014.

34. StephanJ, FrankeJ, Ehrenhofer-MurrayAE (2013) Chemical genetic screen in fission yeast reveals roles for vacuolar acidification, mitochondrial fission, and cellular GMP levels in lifespan extension. Aging cell 12 : 574–583 Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23521895. Accessed 27 January 2014.

35. SuzukiSW, OnoderaJ, OhsumiY (2011) Starvation induced cell death in autophagy-defective yeast mutants is caused by mitochondria dysfunction. PLoS One 6: e17412 Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=21364763.

36. MatecicM, SmithDL, PanX, MaqaniN, BekiranovS, et al. (2010) A microarray-based genetic screen for yeast chronological aging factors. PLoS genetics 6: e1000921 Available: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=2858703&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. Accessed 26 January 2014.

37. PowersRW3rd, KaeberleinM, CaldwellSD, KennedyBK, FieldsS (2006) Extension of chronological life span in yeast by decreased TOR pathway signaling. Genes Dev 20 : 174–184 Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=16418483.

38. GueldenerU, HeinischJ, KoehlerGJ, VossD, HegemannJH (2002) A second set of loxP marker cassettes for Cre-mediated multiple gene knockouts in budding yeast. Nucleic Acids Res 30: e23 Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=11884642.

39. GuldenerU, HeckS, FielderT, BeinhauerJ, HegemannJH (1996) A new efficient gene disruption cassette for repeated use in budding yeast. Nucleic Acids Res 24 : 2519–2524 Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=8692690.

40. JankeC, MagieraMM, RathfelderN, TaxisC, ReberS, et al. (2004) A versatile toolbox for PCR-based tagging of yeast genes: new fluorescent proteins, more markers and promoter substitution cassettes. Yeast 21 : 947–962 Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=15334558.

41. GietzRD, SchiestlRH, WillemsAR, WoodsRA (1995) Studies on the transformation of intact yeast cells by the LiAc/SS-DNA/PEG procedure. Yeast (Chichester, England) 11 : 355–360 Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7785336. Accessed 4 June 2013.

42. RuckenstuhlC, ButtnerS, Carmona-GutierrezD, EisenbergT, KroemerG, et al. (2009) The Warburg effect suppresses oxidative stress induced apoptosis in a yeast model for cancer. PLoS One 4: e4592 Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=19240798.

43. Büttner S, Carmona-Gutierrez D, Vitale I, Castedo M, Ruli D, et al.. (2007) Depletion of endonuclease G selectively kills polyploid cells. Cell cycle (Georgetown, Tex) 6: : 1072–1076. Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17471024. Accessed 29 January 2014.

44. NodaT, KlionskyDJ (2008) The quantitative Pho8Delta60 assay of nonspecific autophagy. Methods in enzymology 451 : 33–42 Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19185711. Accessed 5 June 2013.

45. CampbellCL, ThorsnessPE (1998) Escape of mitochondrial DNA to the nucleus in yme1 yeast is mediated by vacuolar-dependent turnover of abnormal mitochondrial compartments. J Cell Sci 111 ((Pt 1) 2455–2464 Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=9683639.

46. MadeoF, HerkerE, MaldenerC, WissingS, LächeltS, et al. (2002) A caspase-related protease regulates apoptosis in yeast. Molecular cell 9 : 911–917 Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11983181. Accessed 13 November 2012.

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukčná medicína

Článek Ribosomal Protein Mutations Induce Autophagy through S6 Kinase Inhibition of the Insulin PathwayČlánek Recent Mitochondrial DNA Mutations Increase the Risk of Developing Common Late-Onset Human DiseasesČlánek G×G×E for Lifespan in : Mitochondrial, Nuclear, and Dietary Interactions that Modify LongevityČlánek PINK1-Parkin Pathway Activity Is Regulated by Degradation of PINK1 in the Mitochondrial MatrixČlánek Rapid Evolution of PARP Genes Suggests a Broad Role for ADP-Ribosylation in Host-Virus ConflictsČlánek The Impact of Population Demography and Selection on the Genetic Architecture of Complex TraitsČlánek The Case for Junk DNA

Článok vyšiel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Najčítanejšie tento týždeň

2014 Číslo 5- Gynekologové a odborníci na reprodukční medicínu se sejdou na prvním virtuálním summitu

- Je „freeze-all“ pro všechny? Odborníci na fertilitu diskutovali na virtuálním summitu

-

Všetky články tohto čísla

- Genetic Interactions Involving Five or More Genes Contribute to a Complex Trait in Yeast

- A Mutation in the Gene in Dogs with Hereditary Footpad Hyperkeratosis (HFH)

- Loss of Function Mutation in the Palmitoyl-Transferase HHAT Leads to Syndromic 46,XY Disorder of Sex Development by Impeding Hedgehog Protein Palmitoylation and Signaling

- Heterogeneity in the Frequency and Characteristics of Homologous Recombination in Pneumococcal Evolution

- Genome-Wide Nucleosome Positioning Is Orchestrated by Genomic Regions Associated with DNase I Hypersensitivity in Rice

- Null Mutation in PGAP1 Impairing Gpi-Anchor Maturation in Patients with Intellectual Disability and Encephalopathy

- Single Nucleotide Variants in Transcription Factors Associate More Tightly with Phenotype than with Gene Expression

- Ribosomal Protein Mutations Induce Autophagy through S6 Kinase Inhibition of the Insulin Pathway

- Recent Mitochondrial DNA Mutations Increase the Risk of Developing Common Late-Onset Human Diseases

- Epistatically Interacting Substitutions Are Enriched during Adaptive Protein Evolution

- Meiotic Drive Impacts Expression and Evolution of X-Linked Genes in Stalk-Eyed Flies

- G×G×E for Lifespan in : Mitochondrial, Nuclear, and Dietary Interactions that Modify Longevity

- Population Genomic Analysis of Ancient and Modern Genomes Yields New Insights into the Genetic Ancestry of the Tyrolean Iceman and the Genetic Structure of Europe

- p53 Requires the Stress Sensor USF1 to Direct Appropriate Cell Fate Decision

- Whole Exome Re-Sequencing Implicates and Cilia Structure and Function in Resistance to Smoking Related Airflow Obstruction

- Allelic Expression of Deleterious Protein-Coding Variants across Human Tissues

- R-loops Associated with Triplet Repeat Expansions Promote Gene Silencing in Friedreich Ataxia and Fragile X Syndrome

- PINK1-Parkin Pathway Activity Is Regulated by Degradation of PINK1 in the Mitochondrial Matrix

- The Impairment of MAGMAS Function in Human Is Responsible for a Severe Skeletal Dysplasia

- Octopamine Neuromodulation Regulates Gr32a-Linked Aggression and Courtship Pathways in Males

- Mlh2 Is an Accessory Factor for DNA Mismatch Repair in

- Activating Transcription Factor 6 Is Necessary and Sufficient for Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Zebrafish

- The Spatiotemporal Program of DNA Replication Is Associated with Specific Combinations of Chromatin Marks in Human Cells

- Rapid Evolution of PARP Genes Suggests a Broad Role for ADP-Ribosylation in Host-Virus Conflicts

- Genome-Wide Inference of Ancestral Recombination Graphs

- Mutations in Four Glycosyl Hydrolases Reveal a Highly Coordinated Pathway for Rhodopsin Biosynthesis and N-Glycan Trimming in

- SHP2 Regulates Chondrocyte Terminal Differentiation, Growth Plate Architecture and Skeletal Cell Fates

- The Impact of Population Demography and Selection on the Genetic Architecture of Complex Traits

- Retinoid-X-Receptors (α/β) in Melanocytes Modulate Innate Immune Responses and Differentially Regulate Cell Survival following UV Irradiation

- Genetic Dissection of the Female Head Transcriptome Reveals Widespread Allelic Heterogeneity

- Genome Sequencing and Comparative Genomics of the Broad Host-Range Pathogen AG8

- Copy Number Variation Is a Fundamental Aspect of the Placental Genome

- GOLPH3 Is Essential for Contractile Ring Formation and Rab11 Localization to the Cleavage Site during Cytokinesis in

- Hox Transcription Factors Access the RNA Polymerase II Machinery through Direct Homeodomain Binding to a Conserved Motif of Mediator Subunit Med19

- Drosha Promotes Splicing of a Pre-microRNA-like Alternative Exon

- Predicting the Minimal Translation Apparatus: Lessons from the Reductive Evolution of

- PAX6 Regulates Melanogenesis in the Retinal Pigmented Epithelium through Feed-Forward Regulatory Interactions with MITF

- Enhanced Interaction between Pseudokinase and Kinase Domains in Gcn2 stimulates eIF2α Phosphorylation in Starved Cells

- A HECT Ubiquitin-Protein Ligase as a Novel Candidate Gene for Altered Quinine and Quinidine Responses in

- dGTP Starvation in Provides New Insights into the Thymineless-Death Phenomenon

- Phosphorylation Modulates Clearance of Alpha-Synuclein Inclusions in a Yeast Model of Parkinson's Disease

- RPM-1 Uses Both Ubiquitin Ligase and Phosphatase-Based Mechanisms to Regulate DLK-1 during Neuronal Development

- More of a Good Thing or Less of a Bad Thing: Gene Copy Number Variation in Polyploid Cells of the Placenta

- More of a Good Thing or Less of a Bad Thing: Gene Copy Number Variation in Polyploid Cells of the Placenta

- Heritable Transmission of Stress Resistance by High Dietary Glucose in

- Revertant Mutation Releases Confined Lethal Mutation, Opening Pandora's Box: A Novel Genetic Pathogenesis

- Lifespan Extension by Methionine Restriction Requires Autophagy-Dependent Vacuolar Acidification

- A Genome-Wide Assessment of the Role of Untagged Copy Number Variants in Type 1 Diabetes

- Selectivity in Genetic Association with Sub-classified Migraine in Women

- A Lack of Parasitic Reduction in the Obligate Parasitic Green Alga

- The Proper Splicing of RNAi Factors Is Critical for Pericentric Heterochromatin Assembly in Fission Yeast

- Discovery and Functional Annotation of SIX6 Variants in Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma

- Six Homeoproteins and a linc-RNA at the Fast MYH Locus Lock Fast Myofiber Terminal Phenotype

- EDR1 Physically Interacts with MKK4/MKK5 and Negatively Regulates a MAP Kinase Cascade to Modulate Plant Innate Immunity

- Genes That Bias Mendelian Segregation

- The Case for Junk DNA

- An In Vivo EGF Receptor Localization Screen in Identifies the Ezrin Homolog ERM-1 as a Temporal Regulator of Signaling

- Mosaic Epigenetic Dysregulation of Ectodermal Cells in Autism Spectrum Disorder

- Hyperactivated Wnt Signaling Induces Synthetic Lethal Interaction with Rb Inactivation by Elevating TORC1 Activities

- Mutations in the Cholesterol Transporter Gene Are Associated with Excessive Hair Overgrowth

- Scribble Modulates the MAPK/Fra1 Pathway to Disrupt Luminal and Ductal Integrity and Suppress Tumour Formation in the Mammary Gland

- A Novel CH Transcription Factor that Regulates Expression Interdependently with GliZ in

- Phosphorylation of a WRKY Transcription Factor by MAPKs Is Required for Pollen Development and Function in

- Bayesian Test for Colocalisation between Pairs of Genetic Association Studies Using Summary Statistics

- Spermatid Cyst Polarization in Depends upon and the CPEB Family Translational Regulator

- Insights into the Genetic Structure and Diversity of 38 South Asian Indians from Deep Whole-Genome Sequencing

- Intron Retention in the 5′UTR of the Novel ZIF2 Transporter Enhances Translation to Promote Zinc Tolerance in

- A Dominant-Negative Mutation of Mouse Causes Glaucoma and Is Semi-lethal via LBD1-Mediated Dimerisation

- Biased, Non-equivalent Gene-Proximal and -Distal Binding Motifs of Orphan Nuclear Receptor TR4 in Primary Human Erythroid Cells

- Ras-Mediated Deregulation of the Circadian Clock in Cancer

- Retinoic Acid-Related Orphan Receptor γ (RORγ): A Novel Participant in the Diurnal Regulation of Hepatic Gluconeogenesis and Insulin Sensitivity

- Extensive Diversity of Prion Strains Is Defined by Differential Chaperone Interactions and Distinct Amyloidogenic Regions

- Fine Tuning of the UPR by the Ubiquitin Ligases Siah1/2

- Paternal Poly (ADP-ribose) Metabolism Modulates Retention of Inheritable Sperm Histones and Early Embryonic Gene Expression

- Allele-Specific Genome-wide Profiling in Human Primary Erythroblasts Reveal Replication Program Organization

- PLOS Genetics

- Archív čísel

- Aktuálne číslo

- Informácie o časopise

Najčítanejšie v tomto čísle- PINK1-Parkin Pathway Activity Is Regulated by Degradation of PINK1 in the Mitochondrial Matrix

- Null Mutation in PGAP1 Impairing Gpi-Anchor Maturation in Patients with Intellectual Disability and Encephalopathy

- Phosphorylation of a WRKY Transcription Factor by MAPKs Is Required for Pollen Development and Function in

- p53 Requires the Stress Sensor USF1 to Direct Appropriate Cell Fate Decision

Prihlásenie#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zabudnuté hesloZadajte e-mailovú adresu, s ktorou ste vytvárali účet. Budú Vám na ňu zasielané informácie k nastaveniu nového hesla.

- Časopisy