-

Články

- Časopisy

- Kurzy

- Témy

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Small RNA Sequences Support a Host Genome Origin of Satellite RNA

Satellite RNAs (satRNAs) are small RNA pathogens in plants that depend on associated viruses for replication and spread. While much is known about the replication and pathogenicity of satRNAs, their origin remains a mystery. We report evidence for a host genome origin of the Cucumber mosaic virus (CMV) satRNA. We show that only the CMV Y-satRNA (Y-Sat) sequence region of a fusion transgene was methylated in Nicotiana tabacum, indicating that the Y-Sat sequence is subject to 24-nt small RNA (sRNA)-directed DNA methylation. 24-nt sRNAs as well as multiple genomic DNA fragments, with sequence homology to Y-Sat, were detected in Nicotiana plants, suggesting that the Nicotiana genome contains Y-Sat-like repetitive DNA sequences, a genomic feature associated with 24-nt sRNAs. Our results suggest that CMV satRNAs have originated from repetitive DNA in the Nicotiana plant genome, and highlight the possibility that small RNA sequences can be used to identify the origin of other satRNAs.

Published in the journal: Small RNA Sequences Support a Host Genome Origin of Satellite RNA. PLoS Genet 11(1): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004906

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1004906Summary

Satellite RNAs (satRNAs) are small RNA pathogens in plants that depend on associated viruses for replication and spread. While much is known about the replication and pathogenicity of satRNAs, their origin remains a mystery. We report evidence for a host genome origin of the Cucumber mosaic virus (CMV) satRNA. We show that only the CMV Y-satRNA (Y-Sat) sequence region of a fusion transgene was methylated in Nicotiana tabacum, indicating that the Y-Sat sequence is subject to 24-nt small RNA (sRNA)-directed DNA methylation. 24-nt sRNAs as well as multiple genomic DNA fragments, with sequence homology to Y-Sat, were detected in Nicotiana plants, suggesting that the Nicotiana genome contains Y-Sat-like repetitive DNA sequences, a genomic feature associated with 24-nt sRNAs. Our results suggest that CMV satRNAs have originated from repetitive DNA in the Nicotiana plant genome, and highlight the possibility that small RNA sequences can be used to identify the origin of other satRNAs.

Introduction

Satellite RNAs (satRNAs) are among the smallest RNA pathogens in plants and depend on associated viruses (helper viruses) for replication, encapsidation and movement inside the host plant [1], [2]. Their RNA genomes range from 220 to 1500 nucleotides (nt) in size and can form compact secondary structures by intra-molecular base-pairing that can be resistant to degradation by ribonucleases. SatRNAs are classified into three classes [3]. Class 1 satRNAs include large mRNA satellites that are 800 to 1500 nt in length and contain a single open reading frame that encodes at least one non-structural protein. SatRNAs belonging to class 2 are linear, less than 700 nt in size and possess no mRNA activity so do not encode any protein. SatRNAs of this class, including the Cucumber mosaic virus (CMV) satRNAs [4], occur most frequently. SatRNAs of class 3 are circular, around 350 to 400 nt in length and also do not exhibit mRNA activity. SatRNAs normally accumulate at high levels in infected host plants relative to their helper viruses, presumably because of the small size and ribonuclease-resistant structure of their RNA genome. A previous study shows that a CMV satRNA, unlike the CMV helper virus, is resistant to host RNA-dependent RNA polymerase-mediated antiviral silencing in Arabidopsis [5], which may also contribute to the high level accumulation of satRNAs. Whereas high-level replication and systemic infection of satRNAs depend on helper virus-encoded proteins, recent studies on CMV satRNAs indicate that satRNAs can be imported into the nucleus and transcribed there by host plant proteins independently of helper viruses [6], [7]. satRNAs are not required for the life cycle of their helper viruses, but participate in helper virus-host interactions by modulating the level of helper virus accumulation and the severity of helper virus-induced symptoms [8]. In addition, satRNAs can induce disease symptoms in the host plants that are distinct from helper virus-caused symptoms [4]. Recent studies indicate that such satRNA-induced symptoms are due to silencing of host genes directed by satRNA-derived small interfering RNAs (siRNA) [9], [10].

Like all plant viruses and subviral agents, the origin of satRNAs remains unclear. Two main origins of satRNA have been suggested: the genome of the helper virus or that of the host plant. However, unlike defective interfering RNAs, a group of subviral RNAs derived from truncated forms of the helper virus genome, satRNAs usually possess little or no sequence homology with their helper viruses [1], which argues against the helper virus genome as their origin. One exception is the virulent satRNA strain of Turnip crinkle virus, which contains a long (166-nt) segment that is homologous to the 3' end of the helper virus genome [11]. A number of studies have suggested satRNA emergence from the host genome. Sequence similarity has been observed between nucleotide stretches of the Arabidopsis genome and CMV satRNAs [1]. SatRNAs, such as CMV satRNAs that occur widely in Nicotiana species and some other Solanaceae species, are more commonly detected in experimental systems than in the wild or nature [1]. A number of studies have reported de novo emergence of satRNAs on serial passaging plants with the helper virus under controlled environmental conditions [12], implicating the host genome as the origin of satRNAs. Another report showed structural similarities of Peanut stunt virus (PSV) satRNAs with cellular introns of nucleus, mitochondria and plant viroids [13]. However, in spite of these suggestions, no intact plant genome sequence with similarities to satRNAs has been reported.

RNA silencing is an evolutionarily conserved gene regulation mechanism in eukaryotes mediated by 20-25-nt small RNAs (sRNAs) [14], [15]. These sRNA are processed from double-stranded (ds) or hairpin (hp) RNA by Dicer or Dicer-like (DCL) protein. To induce silencing, one strand of a sRNA is loaded into an Argonaute (AGO) protein to form the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), and guides the RISC to bind to complementary single-stranded RNA and cleave the RNA. Plants have three basic types of sRNA, 20-24-nt microRNA (miRNA), 21-22-nt siRNA, and 24-nt repeat-associated siRNA (rasiRNA) [16], [17]. MiRNAs induce posttranscriptional degradation or translational repression of mRNAs that encode regulatory proteins, such as transcription factors, and play a key role in plant development [17], [18]. The 21-22-nt siRNAs direct degradation of viral RNA and some endogenous mRNA, and are important in plant defence against viruses and in the control of some endogenous genes [17], [19]. The 24-nt rasiRNAs are unique to plants, and are involved in RNA-directed DNA methylation (RdDM) which is important for maintaining genome stability by silencing transposons and repetitive DNA sequences [17], [20], [21]. RdDM is highly sequence specific, and can be induced by both endogenous siRNAs and siRNAs derived from infecting viral agents including satRNAs [20], [22].

During the analysis of a transgene (35S-GUS:Sat) containing a β-glucuronidase (GUS) sequence transcriptionally fused at the 3′ end with the CMV Y-satellite RNA (Y-Sat) sequence in Nicotiana tabacum, we observed that the Y-Sat sequence was specifically methylated. This led us to hypothesize that 24-nt siRNAs homologous to Y-Sat may exist in N. tabacum inducing RdDM at the Y-Sat sequence of the transgene. Subsequent analyses revealed the existence of both 24-nt sRNAs and multiple DNA fragments in Nicotiana plants that showed sequence homology to Y-Sat, suggesting that CMV satRNAs originate from repetitive regions in the Nicotiana genome.

Results

35S-GUS:Sat transgenes are repressed in transgenic tobacco

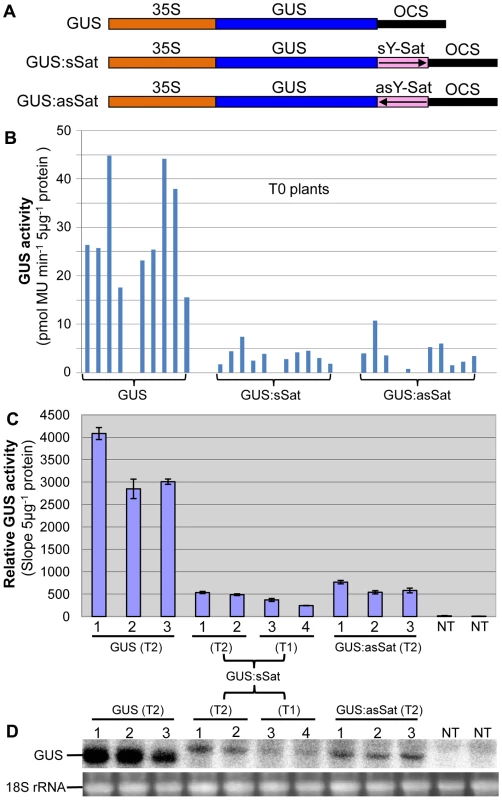

Three 35S promoter-driven GUS constructs were created, two of which had a 3′ fusion of a full-length 369-nt Y-Sat sequence [23] in either the sense (sSat) or antisense (asSat) orientation (Fig. 1A). These were transformed into tobacco and multiple independent transgenic lines obtained for each.

Fig. 1. The 35S-GUS:Sat fusion transgenes show repressed expression in N. tabacum in comparison to the 35S-GUS transgene.

(A) Schematic diagrams of the transgene constructs. (B) MUG assay of independent primary (T0) transformants. (C) MUG assay of second (T1) and third-generation (T2) transformants, plus non-transgenic (NT) control plants. (D) mRNA northern blot analysis of the plants shown in (C). Note: the different units in the Y-axis of the two MUG assay histograms are due to the use of different fluoroscan machines and different ways of calculation. Plants transformed with the 35S-GUS:Sat fusion constructs showed reduced levels of GUS protein in comparison to those transformed with just the 35S-GUS construct lacking the Y-Sat sequence (Fig. 1B, 1C). This reduction in GUS activity occurred for both the sense and antisense orientations of the Y-Sat sequence (Fig. 1B). The low level of GUS activity was relatively uniform across the independent primary (T0) transformants (Fig. 1B) and persisted in the subsequent (T1 and T2) generations (Fig. 1C). The MUG assay results were confirmed by northern blot hybridization, which showed that the GUS:sSat and GUS:asSat transcripts accumulated at a much lower level than the GUS transcript in the respective transgenic plants (Fig. 1D).

The reduced expression of the 35S-GUS:sSat transgene is due to transcriptional repression

The repressed expression of the 35S-GUS:Sat transgenes could either be due to transcriptional (TGS) or posttranscriptional (PTGS) gene silencing or to transcript instability caused by the fused Y-Sat sequence. Since both the 35S-GUS:sSat and 35S-GUS:asSat transgenes showed similar reduction in expression, the secondary structures of the fusion sequence were not likely to be responsible for the repression, as sense and antisense Y-Sat sequences are predicted to form different secondary structures. It also implied that RNA instability was not the main cause for the repressed GUS:Sat trangene expression. This was supported by results from an Agrobacterium infiltration (agro-infiltration) assay where both TGS and PTGS were negated, which showed that the large difference in expression levels between the 35S-GUS and 35S-GUS:sSat transgenes observed in stably transformed plants (∼6 fold; Fig. 1) was dramatically reduced in the agro-infiltrated tissues (∼1.0–2.4 fold; S1 Fig.).

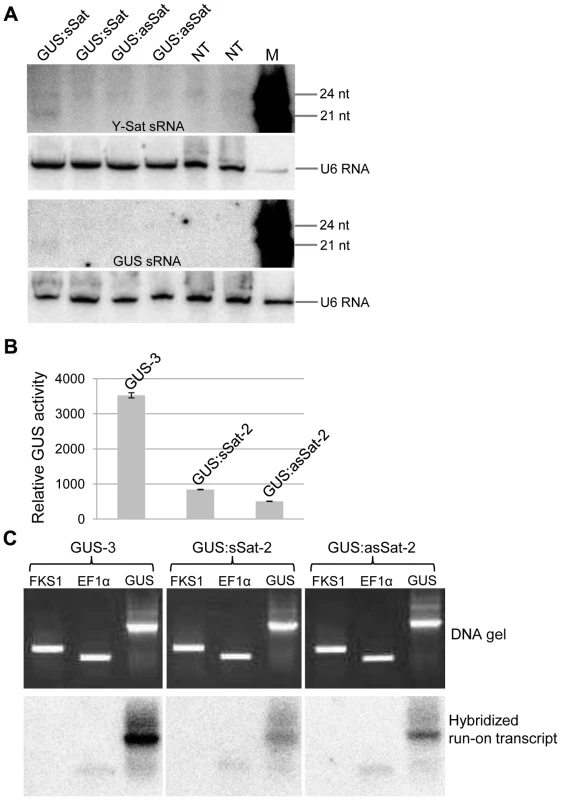

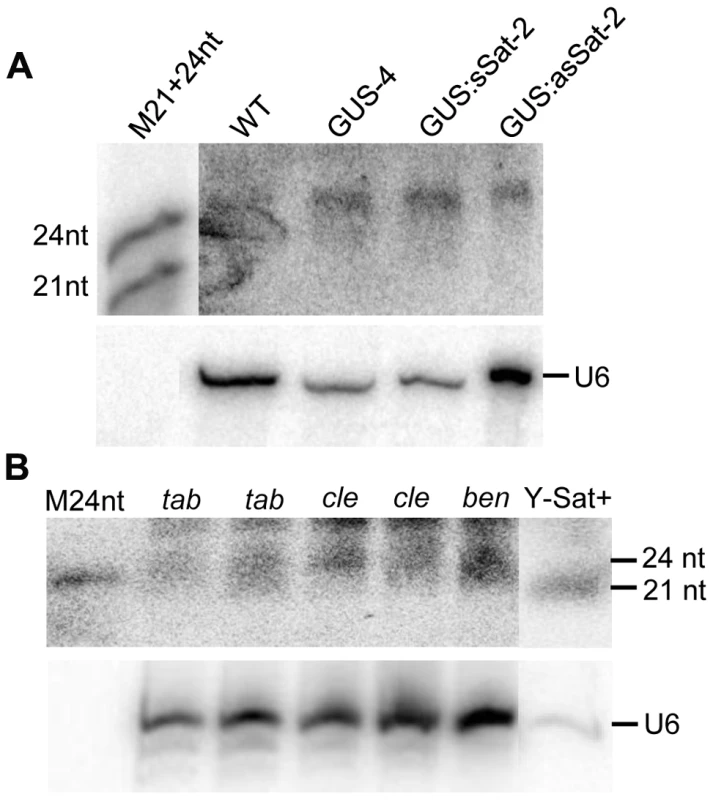

We next investigated if PTGS or TGS was responsible for the repressed expression of the 35S-GUS:Sat transgenes. PTGS of a transgene is associated with 21-nt siRNAs corresponding to the transcribed region [17]. Northern blot hybridization failed to detect GUS - or Y-Sat-specific 21-nt siRNAs in three of the four 35S-GUS:Sat transgenic lines analysed (Fig. 2A), suggesting that TGS, but not PTGS, was the main cause of transgene repression. Consistent with this, nuclear run-on assay showed that the repressed 35S-GUS:sSat and 35S-GUS:asSat transgenes generated much reduced RNA signals in comparison to the highly expressed 35S-GUS transgene (Fig. 2B, C), indicating that they are transcriptionally repressed.

Fig. 2. The 35S-GUS:Sat transgene is transcriptionally repressed.

(A) Three of the four 35S-GUS:Sat transgenic lines analysed show no detectable accumulation of 21-nt PTGS-associated GUS or Y-Sat-specific siRNAs, indicating that PTGS is not the main cause of 35S-GUS:Sat transgene repression. M, 21 and 24-nt small RNA size markers. (B) and (C) The highly expressed 35S-GUS line (GUS-3) (B) generates much stronger nuclear run-on transcript signals than the two repressed 35S-GUS:Sat lines (C), indicating that the reduced expression of the 35S-GUS:Sat transgenes results from transcriptional repression. FKS1 and EF1α are negative control and internal reference gene sequences, respectively. The Y-Sat DNA sequence in the 35S-GUS:Sat fusion transgenes is specifically methylated in transgenic N. tabacum

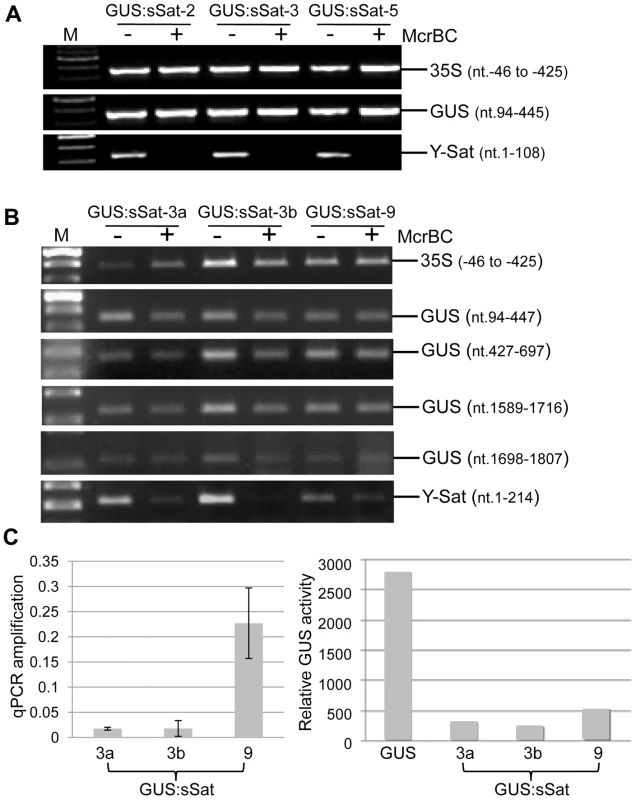

As DNA methylation at promoter sequences can cause TGS [24], we investigated if DNA methylation occurred in the 35S promoter of the 35S-GUS:sSat transgene using McrBC digestion-PCR. McrBC is a methylation-dependent restriction enzyme that recognizes DNA containing two or more methylated cytosine residues, separated by 30–2000 base pairs, and cleaves the DNA at multiple sites close to one of the methylated cytosines. Differences in PCR-amplified McrBC-digested and undigested DNA can provide a measurement of DNA methylation levels. McrBC digestion did not result in clear reduction in the amplification of a 380-bp amplicon, derived from the the 35S promoter near the transcription start site, which contains a total of 175 cytosines from both strands (Fig. 3). This indicated that the 35S promoter in the 35S-GUS:sSat transgene was not methylated, and that the reduced transgene expression was not due to promoter methylation. We extended the DNA methylation analysis to the GUS and Y-Sat sequence of the transgene. Similar to the 35S promoter sequence, four different regions of the GUS coding sequence showed no clear methylation, as indicated by strong amplification of McrBC-digested DNA (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Methylation analysis of the 35S-GUS:sSat transgene in transgenic N. tabacum using McrBC PCR.

(A) and (B) McrBC PCR of 35S promoter, different regions of GUS coding sequence, and Y-Sat. (C) qPCR quantification of McrBC digestion of the Y-Sat sequence shown in (B) (nt. 1-214) (left) and MUG assay of GUS activity in the transgenic plants used for the McrBC PCR analysis (right). M, DNA size marker. In contrast to the 35S and GUS sequences, McrBC digestion strongly reduced PCR amplification of the Y-Sat sequence in the 35S-GUS:sSat transgene (Fig. 3), indicating that it was highly methylated. Furthermore, the degree of this methylation, as judged by the extent of reduction in PCR amplification upon McrBC digestion (Fig. 3B and C, left), appeared to be inversely correlated with the level of GUS activity in the 35S-GUS:sSat plants (Fig. 3C, right). McrBC PCR also indicated Y-Sat-specific DNA methylation in the 35S-GUS:asSat transgene that contains an antisense Y-Sat sequence (S2 Fig.). Both the 35S and GUS sequences showed no difference in PCR amplification between McrBC-digested and undigested DNA, whereas the Y-Sat sequence showed a clear reduction in amplification upon McrBC digestion. Furthermore, the expression level of the 35S-GUS:asSat transgene also appeared to be inversely correlated with the extent of Y-Sat sequence methylation (S2 Fig.).

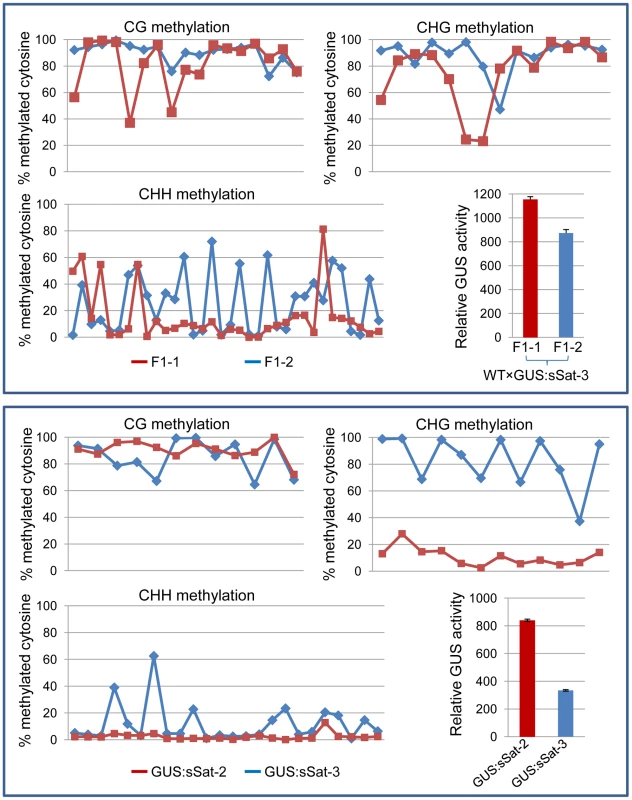

The McrBC PCR results were validated using bisulfite sequencing, which determines DNA methylation at a single cytosine nucleotide level due to the ability of bisulfite to convert unmethylated, but not methylated, cytosines to uracils [25]. Three regions of the 35S-GUS:sSat transgene were amplified from bisulfite-converted DNA, including the 35S promoter, the 35S-GUS junction, and the Y-Sat sequence (S3A Fig.). We sequenced the bisulfite PCR product as a mixed DNA population, and determined the DNA methylation level based on the ratio between the peak heights of cytosine (C) and thymine (T) residues in the sequencing trace files, which has proven to be an effective way for measuring overall DNA methylation levels in a specific plant sample [26]. Consistent with the McrBC PCR result, the 35S and GUS sequences showed no significant methylation of cytosine residues as indicated by the lack of cytosine (blue) peaks at the cytosine positions in the trace files, which were instead replaced by thymine (red) peaks (S3B-C Fig.). In contrast, the Y-Sat sequence showed strong methylation in all four DNA samples analyzed, especially at the CG and CHG sites (H = A, C or T nucleotides) (Fig. 4). Two pairs of 35S-GUS:sSat transgenic lines were analyzed by bisulfite sequencing, and in each pair the plants that showed lower GUS expression level displayed a higher degree of cytosine methylation, particularly at the CHG and CHH sites (Fig. 4). Taken together, the DNA methylation analyses indicated that the Y-Sat sequence of the 35S-GUS:Sat transgenes was specifically targeted for methylation in transgenic N. tabacum plants, and that this methylation appeared to correlate with the repression of the transgenes.

Fig. 4. Bisulfite sequencing shows strong DNA methylation in the Y-Sat sequence of the 35S-GUS:sSat transgene in all cytosine contexts, particularly at the CG and CHG sites.

The methylation status of cytosines in CG, CHG and CHH contexts is presented separately in three line graphs. Each point on the line represents a cytosine in a sequential 5′ to 3′ order along the bisulfite-sequenced Y-Sat sequence, with the Y-axis showing the percentage of methylated cytosines (based on the ratio of cytosine peak height in the trace file) at each of these positions. The top panel shows the methylation pattern of two F1 sibling plants derived from a cross between WT N. tabacum (as the maternal parent) and a 35S-GUS:sSat transgenic line. The bottom panel shows the methylation pattern of two independent 35S-GUS:sSat transgenic lines. Note that in both cases the plant showing a higher level of GUS expression (F1-1 or GUS:sSat-2, shown in red) displays a lower degree of CHG and CHH methylation in the Y-Sat sequence. Y-Sat-like 24-nt sRNAs are detected in Nicotiana plants using northern blot hybridization

The sequence-specific DNA methylation detected in the Y-Sat sequence of the 35S-GUS:Sat transgenes raised the possibility that the Y-Sat sequence might be subject to RNA-directed DNA methylation (RdDM). RdDM can occur at all cytosine contexts (CG, CHG and CHH), and is directed by the 24-nt size class of siRNAs [17], [20], [21]. sRNAs of 24 nt, but not of 21–22 nt, were readily detectable in both transgenic and wild-type Nicotiana plants by northern blot hybridization using the Y-Sat sequence as a probe, especially in the flowers (Fig. 5A), a tissue known to contain relatively high abundance of 24-nt siRNAs [27], [28]. Importantly, the 24-nt sRNA signals were not affected by the presence of the 35S-GUS:Sat fusion transgenes (Fig. 5A and 2A), indicating that they are generated by the host plant genome and not by the transgene. Northern blot hybridization also showed that these 24-nt Y-Sat-like sRNAs are present in all three Nicotiana species analysed (Fig. 5B). These results indicated that Nicotiana species generate 24-nt sRNAs with sequence homology to the Y-Sat, and suggested that the DNA methylation of the Y-Sat sequence in the fusion transgenes was likely induced by these 24-nt sRNAs.

Fig. 5. sRNAs of 24 nt in size are readily detectable in Nicotiana plants using Y-Sat probe.

(A) The 24 nt siRNAs are detected in the flowers of both WT and 35S-GUS, 35S-GUS:sSat, 35S-GUS:asSat transgenic N. tabacum plants. M21+24nt, 21 and 24-nt small RNA size marker. (B) 24 nt siRNAs are detectable in leaf tissues of three different Nicotiana species, N. tabacum (tab), N. clevelandii (cle), and N. benthamiana (ben). “Y-Sat+” is a RNA sample derived from a Y-Sat-infected N. tabacum plant, which was under-exposed to show the dominant ∼21-nt Y-Sat-derived siRNAs. M24nt, 24-nt small RNA size marker. Both hybridized blots were treated with RNase A before exposure. Host-derived Y-Sat-like 24 nt sRNAs are detected in Nicotiana plants by sRNA deep sequencing

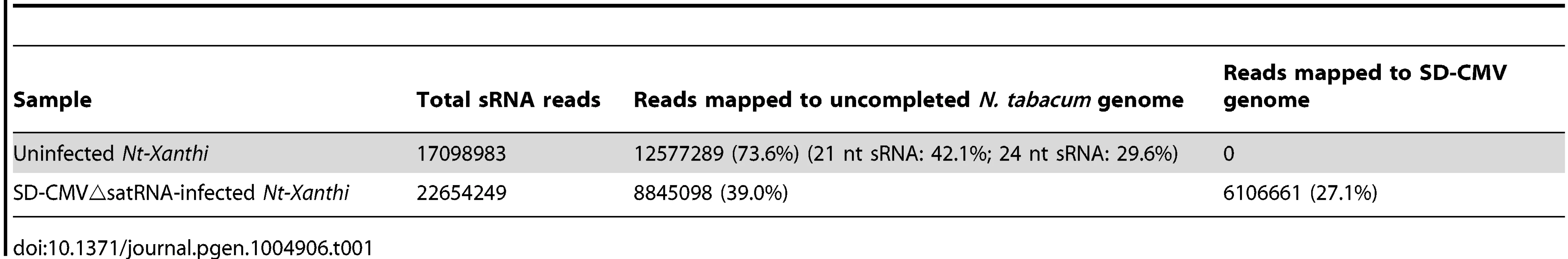

Detection of 24-nt Y-Sat-like sRNAs in wild-type Nicotiana plants using northern blot hybridization prompted us to identify the nucleotide sequences of these sRNAs using Illumina sequencing. To avoid possible contamination by CMV Y-Sat (used in our Canberra laboratory), leaf samples from uninfected N. tabacum cv. Xanthi nc (Nt-Xanthi) grown under insect-proof conditions (in our Beijing laboratory where the CMV Shandong strain (SD-CMV) was used) were collected for sRNA extraction and sequencing. To investigate if CMV infection might affect the accumulation of Y-Sat-like sRNAs, we also sequenced sRNAs isolated from Nt-Xanthi infected with SD-CMVΔsatR, an infectious CMV clone devoid of SD-satRNA [29]. Approximately 17 and 23 million clean reads of sRNAs were obtained from the uninfected and SD-CMVΔsatR-infected plants, respectively, with 73.6% and 39% mapping perfectly to the uncompleted N. tabacum genome (ftp.sgn.cornel.edu) (Table 1). These N. tabacum-matching sRNAs were dominated by the 21 and 24-nt size classes (Table 1), consistent with the size distribution expected for plant sRNAs [30]. A large number of sRNAs matching the SD-CMV genome (27%) were identified in the sRNA sequencing data from SD-CMVΔsatR-infected plants, but none from the uninfected plants (Table 1). The majority (85.1%) of these SD-CMV-derived sRNAs was 21-22-nt in size, consistent with previous reports of sRNA distribution patterns from RNA viruses [19].

Tab. 1. Summary of sRNA sequencing data from uninfected and CMV△satRNA-infected <i>Nt. Xanthi</i>.

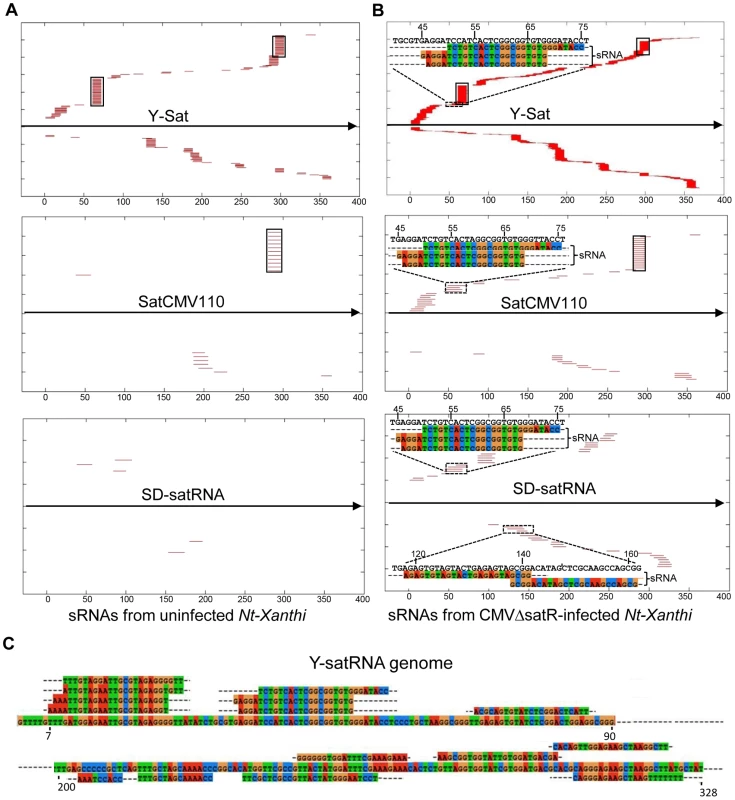

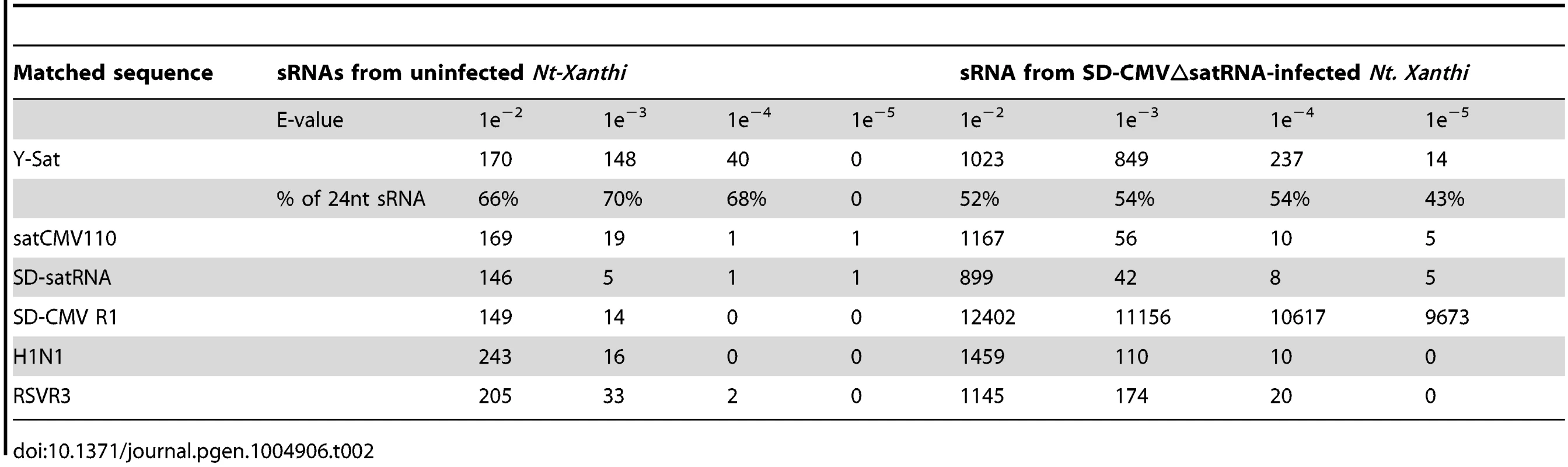

To identify Y-Sat-like sRNAs produced from the tobacco genome, the total sRNA reads were compared against the Y-Sat genome using BLASTN with varying statistical significance determined by E-values (i.e. the lower the E-value the greater the statistical significance of the match). Two additional CMV satRNA sequences (satCMV110 and SD-satRNA) were also used for comparison along with three randomly chosen similar sized (∼360 nt) non-satRNA sequences (SD-CMV RNA1, Influenza A virus subtype H1N1 and Rice stripe virus RNA3 genome sequences) as negative controls.

The number of matching sRNAs was generally increased in the SD-CMVΔsatR-infected sample compared to the uninfected sample (Table 2 and Fig. 6). At a low-stringency E-value (le−2), there was no significant difference in the number of sRNAs aligning to the three CMV satRNAs versus the three control sequences. However, using greater E-value stringencies (i.e. le−3, le−4 and le−5) to improve the alignment quality led to a higher frequency of sRNAs aligning to the Y-Sat genome than the control sequences in both the uninfected and particularly the SD-CMV△satRNA-infected samples (Table 2 and Fig. 6A, 6B). A large proportion of these Y-Sat-matching sRNAs were 24 nt in size (Table 2). The satCMV110 and SD-satRNA also had more aligning sRNAs in the SD-CMV△satRNA-infected sample than the control sequences when using the higher alignment stringency (Table 2). In fact, no sRNA aligned to the relevant control sequences when using an E-value of le−5, with the exception of sRNAs aligning to the SD-CMV control sequence, which is a result of the SD-CMV infection (Table 2). The 14 unique Y-Sat-matching sRNA sequences aligned with both the 5′ and 3′ regions of the Y-Sat genome (Fig. 6C), suggesting the possible existence of long stretches of Y-Sat-like sequences in the N. tabacum genome. The five SD-satRNA-matching sRNAs identified in the SD-CMVΔsatR-infected sample (1e−5) showed perfect sequence identity to the SD-satRNA genome, and had a size range of 23–26 nt (one 23-nt, one 26-nt and three 24-nt; Fig. 6B, the bottom panel; the colour-coded sequences). Three of these SD-matching sRNAs also aligned with the nt. 45–74 region of the Y-Sat and satCMV110 genomes (Fig. 6B, the top and middle panels; the colour-coded sequences). Taken together, the sRNA sequencing data indicated the presence of 24-nt sRNAs in the N. tabacum genome with sequence homologies to CMV satRNAs, particularly to Y-Sat, which could account for the 24-nt sRNA signals detected by northern blot (Fig. 5) and explain the DNA methylation of the Y-Sat sequence in the 35S-GUS:Sat transgenes (Fig. 3, 4 and S2 Fig.). It is noteworthy that the majority of the CMV satRNA-matching sRNAs could not be mapped to the uncompleted N. tabacum genome (S1 Table), indicating that these sRNAs are derived from the unannotated regions of the genome.

Fig. 6. Alignment of sRNAs to three CMV satRNA genome sequences at the E-value of 1e−3 (A and B) and 1e−5 (C).

(A) sRNAs from uninfected N. tabacum Xanthi plants. (B) sRNAs from SD-CMV△satR-infected N. tabacum Xanthi plants. sRNAs matching the satRNA plus-strand and minus-strand are shown as short thin lines above and below the arrow-headed black lines, respectively. sRNAs mapping to the two most conserved regions of CMV satRNAs (nt. 60–80 and nt. 280–300; see S5 Fig.) are boxed. The five sRNAs perfectly matching to SD-satRNA, or nearly perfectly matching (for three of the five sRNAs) to Y-Sat and satCMV110, are shown as color-coded sequences and their respective nucleotide positions in the satRNA genome indicated. (C) Sequence and location of the 14 sRNAs identified from CMVΔsatR-infected Nt-Xanthi plants that map to the Y-Sat genome (the relevant part of the Y-Sat genome sequence, from nt. 1–90 and from nt. 200–328, is also shown). Tab. 2. Number of unique sRNA sequence hits to target sequence under different stringency of sequence match (E-value).

The CMV satRNA-matching sRNAs were more frequently aligning to certain regions of the satRNA genomes (Fig. 6 and S4 Fig.). Interestingly, these sRNA “hotspots” were relatively conserved among the three different satRNAs (boxed in Fig. 6 and S4 Fig.) and corresponded to conserved sequence regions among all CMV satRNA genomes (S5 Fig.). Among the three CMV satRNAs, SD-satRNA showed the most divergent distribution pattern of aligning sRNAs (Fig. 6A, B). Phylogenetic analysis of all published CMV satRNA sequences revealed that SD-satRNA, Y-Sat and satCMV110 are grouped into three distinct clusters, with SD-satRNA being the most ancient among the three (S6 Fig.).

The Nicotiana genome contains multiple Y-Sat-like DNA fragments

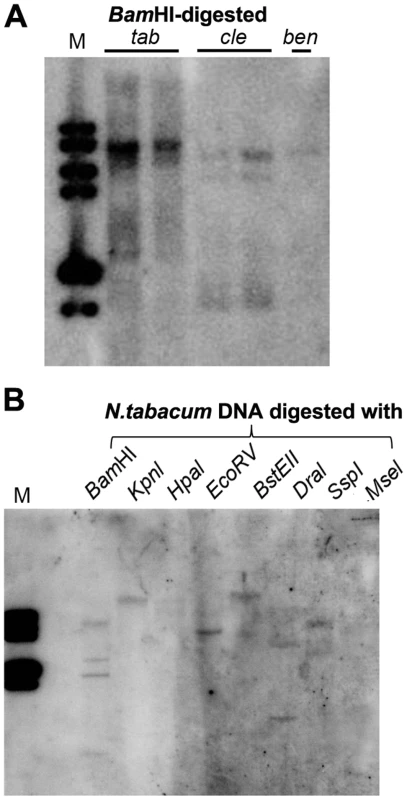

In plants, 24-nt siRNAs are usually derived from repetitive DNA regions such as transposable element (TE) sequences in the genome [30]. Multiple hybridizing DNA bands were detected in N. tabacum, N. clevelandii, and N. benthamiana plants by Southern blotting using the Y-Sat sequence as a probe (Fig. 7A). The different band patterns among the three Nicotiana species ruled out plasmid DNA contamination in the DNA samples. We also observed differences in the intensity of the hybridization signals, which suggested that Y-Sat-like DNA sequences exist in the Nicotiana species but with different copy numbers. Digestion of N. tabacum DNA with various restriction enzymes confirmed the existence of multiple copies of the Y-Sat-like DNA sequences (Fig. 7B).

Fig. 7. Multiple DNA bands are detectable in Nicotiana species that show homology to Y-Sat.

(A) One or multiple bands are detected in BamHI-digested DNA of N. tabacum (tab), N. clevelandii (cle), and N. benthamiana (ben). (B) Digestion of N. tabacum DNA with different enzymes gives different band patterns. M, DNA size marker (1 kb DNA ladder). Discussion

In this study we observed that a GUS transgene fused to the CMV Y-Sat sequence was transcriptionally repressed in N. tabacum plants in comparison to a non-fusion GUS transgene. Transcriptional gene silencing of a transgene is usually caused by promoter methylation and characterized by complete or near-complete silencing of the transgene in a subset of transgenic lines [31], [32]. However, the 35S-GUS:Sat transgenes showed low but consistent levels of GUS expression across the independent transgenic lines. Furthermore, the 35S promoter was not methylated, suggesting that the repression of the 35S-GUS:Sat transgene is not due to conventional TGS.

Both McrBC PCR and bisulfite sequencing detected high levels of DNA methylation in the transcribed region of the 35S-GUS:Sat transgene, with the methylation restricted to the Y-Sat sequence. The extent of methylation in the Y-Sat sequence appeared to be inversely correlated to the level of 35S-GUS:Sat transgene expression, suggesting that this methylation may play a direct role in the repression of the transgene. How DNA methylation in the transcribed region represses the transcription of the 35S-GUS:Sat transgene remains to be investigated. However, our finding provides the first example of transgene repression associated with host-induced methylation targeted to a specific sequence in the transcribed region. The Y-Sat-specific DNA methylation is similar to that observed for the Cereal yellow dwarf virus (CYDV) satRNA sequence of a GUS:CYDV-satRNA fusion transgene in N. tabacum [22]. The sequence-specific methylation of the CYDV sequence is caused by RdDM directed by sRNAs derived from replicating CYDV satRNA [22], also implicating RdDM as the cause of Y-Sat-specific methylation. However, methylation of the Y-Sat sequence occurred in the absence of replicating Y-Sat, suggesting that it was directed by host sRNA-induced RdDM.

Consistent with host-derived sRNA-induced RdDM being responsible for the methylation of the Y-Sat sequence, sRNAs with sequence homology to Y-Sat were readily detected by both northern blot hybridization and sRNA deep sequencing. Importantly, these sRNAs were primarily 24-nt in size, which are known to direct RdDM. This size distribution is different to that of sRNAs derived from replicating satRNAs, which are dominated by 21-22-nt size classes [19], ruling out contaminating satRNAs as the source of these sRNAs. In plants, 24-nt sRNAs are derived primarily from repetitive DNA sequences including TE sequences. Indeed, Southern blot analysis detected multiple DNA fragments in the Nicotiana genome with sequence homology to the Y-Sat sequence. Furthermore, the majority of the Y-Sat-matching sRNAs could not be mapped to the published N. tabacum genome sequence, suggesting that they are likely derived from highly repetitive regions of the genome that are usually difficult to assemble during genome sequencing and hence poorly annotated. Consistent with this possibility, a BLASTN search of the published genome sequences of Nicotiana species and two other Solanaceae species Solanum lycopersicum (tomato) and S. tuberosum (potato) did not yield any long (>20 bp) stretches of Y-Sat-like sequences, again implicating unassembled, repetitive regions as the source of the Y-Sat-matching sRNAs. Taken together, our results suggest that the Nicotiana genome contains Y-Sat-like DNA sequences, and that these sequences exist as repetitive DNA giving rise to 24-nt rasiRNA-like sRNAs that induce RdDM against the Y-Sat sequence in the 35S-GUS:Sat transgene. In addition to RdDM, 24-nt siRNAs have previously been shown to be capable of directing RNA degradation [33]. It would be interesting to examine if these host-derived 24-nt siRNAs play a role in the trilateral host-CMV-satRNA interaction by targeting satRNAs affecting satRNA accumulation.

Our results raise the possibility that CMV satRNAs originate from repetitive DNA elements in the Nicotiana genome. It has previously been speculated that satRNAs could be generated from the host plant under some unique conditions, such as helper virus infection [1]. Our sRNA sequencing showed that Y-Sat-like sRNAs accumulated at a much higher level in CMV-infected than uninfected N. tabacum plants. This implies that the Y-Sat-like repetitive DNA is transcriptionally repressed under normal conditions by DNA methylation, but is activated by CMV infection, possibly via the function of the 2b silencing suppressor that can repress DNA methylation in plants [34]. This would result in increased levels of transcript from repetitive DNA regions, including the Y-Sat-like DNA repeats, which could serve not only as substrate for sRNA production, but also as potential progenitor of CMV satRNAs. This scenario is consistent with the CMV-infected samples containing a much larger proportion of sRNAs that could not be mapped to the published N. tabacum genome than the uninfected samples (S1 Table). Viral replicases or RNA-dependent RNA polymerases have relatively high error rates [35], so replication of viral RNAs including satRNAs can be accompanied by a high rate of nucleotide mutations. Furthermore, for the host-derived progenitor RNAs to become satRNAs, they may need to undergo sequence changes to gain nucleotide motifs for efficient replication and encapsidation, and to gain stable secondary structures for resistance to nucleases. Thus, satRNAs, originating from the host, are likely to have substantial sequence variations from the original DNA or RNA sequences of the host genome. This would explain why most of the Y-Sat-matching N. tabacum sRNAs did not share perfect sequence identities with the Y-Sat genome. Our results do not rule out the possibility that the Y-Sat-like sequences in the N. tabacum genome was originally acquired from a viral genome like the non-retroviral RNA virus elements recently discovered in both plants and animals [36], [37]. However, the fact that CMV satRNAs lack the ability to self-replicate and possess no sequence homology with their helper viruses, together with the previous observation of de novo emergence of satRNAs during serial passaging plants with CMV infection under controlled environmental conditions [12], favours the view that the satRNAs originate from the sequence of the Nicotiana genome.

Our sRNA sequencing data indicated that different CMV satRNAs have different levels of sequence homology to the N. tabacum sRNAs. One possible explanation for this is that the different satRNAs originated from different Nicotiana species, or from different copies of repetitive DNA in one Nicotiana species, that have nucleotide variations. Another possibility is that these satRNAs originated from the Nicotiana genome at different times, with the more ancient ones having greater sequence divergence from the host genome than the more recent ones. This possibility is supported by the phylogenetic analysis of CMV satRNAs, showing the SD-satRNA to be more ancient than Y-Sat, which coincides with N. tabacum sRNAs matching better to Y-Sat than SD-satRNA.

In conclusion, by studying the abnormally repressed expression pattern of the 35S-GUS:Sat transgenes in Nicotiana plants, we have generated evidence indicating that CMV satRNAs have originated from repetitive DNA regions in the Nicotiana genome. Our study suggests that a small RNA sequence-based approach can be used to find the origin of satRNAs.

Materials and Methods

Plasmid construction, plant transformation, and Agrobacterium infiltration

The 35S-GUS-Ocs cassette, prepared using the pART7 plasmid [38], was previously described [39]. The cassette was excised using NotI and inserted into the NotI site of pART27 that contains a NPTII kanamycin resistance gene as the selectable marker for plant transformation [38], resulting in the 35S-GUS construct. For the 35S-GUS:sSat and 35S-GUS:asGUS constructs, the CMV 369-nt Y-Sat sequence was assembled using four long overlapping oligonucleotides (Y-Sat2, 3, 4 and 5; S2 Table), then PCR-amplified using Y-Sat1 and Y-Sat6 that contained a HindIII restriction site, and cloned into pGEMT-Easy vector (Promega). The full-length Y-Sat fragment was then excised with HindIII and inserted into the HindIII site between the GUS and Ocs sequence in the 35S-GUS-Ocs cassette in either the sense or antisense orientation. The resulting 35S-GUS:sSat-Ocs and 35S-GUS:asSat-Ocs cassettes were then excised with NotI and inserted into pART27 at the NotI site, forming the 35S-GUS:sSat and 35S-GUS:asSat constructs, respectively.

For transformation of N. tabacum Wisconsin 38 (W38), the constructs were introduced into Agrobacterium tumefaciens LBA4404 via triparental mating. For Agrobacterium infiltration assay, the constructs were transformed into A. tumefaciens GV3101.

Transformation of N. tabacum W38 was performed as previously described [10] using 50 mg/L kanamycin as the selective agent plus 150 mg/L timentin to inhibit Agrobacterium growth. Transformed plants with established roots were transferred to soil and grown at 25°C under natural light.

Agro-infiltration of N. benthamiana leaves was carried out essentially as described previously [40] with minor modifications. Basically, A. tumefaciens strains containing respective plant expression constructs, including a green florescent protein (GFP) construct as a visual marker and a P19 construct as the RNA silencing suppressor [41], were grown overnight at 28°C in Luria-Bertani medium (LB) containing appropriate antibiotics. After centrifugation, Agrobacterium cells were re-suspended in buffer containing 10 mM MgCl2 and 150 µM acetosyringone, to a final optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 1.0. Agrobacterium cell suspension containing either the 35S-GUS or the 35S-GUS:sSat construct was mixed with the GFP and P19 cell suspensions at a 1∶1∶1 ratio, incubated at room temperature for ∼3 h, and then infiltrated into expanded N. benthamiana leaves using a flat-pointed syringe. For protein and RNA isolation, agro-infiltrated leaf sections at 4 or 5 days post agroinfiltration (dpa) were visualized under a blue light torch (NightSea™, DFP-1™, for exciting green light emission), excised with a pair of scissors and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen.

Southern and Northern blot hybridization

Genomic DNA used for Southern blot hybridization and bisulfite conversion was isolated using the CTAB method described by Draper and Scott [42]. Restriction digestion of DNA (∼20 µg), purification, agarose gel electrophoresis and Southern blot hybridization were essentially as previously described [39]. A HindIII fragment containing the full-length Y-Sat sequence was excised from the pGEM-T Easy clone described above, and used for preparing a 32P-labelled probe using the Megaprime DNA Labelling System (Amersham Biosciences). Hybridized membranes were washed with 1×SSC first at room temperature for 20 min, then at 50°C for 20 min, and finally at 60–65°C for 30 min. The blots were visualized using a phosphorimager (FLA-5000, Fuji Photo Film).

RNA used for small RNA northern blot hybridization was isolated from agro-infiltrated N. benthamiana leaf tissues or transgenic N. tabacum leaves using Trizol Reagent (Invitrogen). For northern blot detection of small RNAs from N. tabacum flowers, total RNAs was isolated using Trizol reagent, high-molecular-weight RNA removed by precipitation with 5% polyethylenglycol 8000 (PEG 8000) and 0.5 M NaCl on ice for 20 min, and small RNAs recovered from the supernatant by precipitation with 3 volumes of ethanol at −20°C for 1 hr. RNA used for northern blot analysis of GUS or GUS:Sat fusion mRNA was isolated using the hot-phenol extraction method [43]. sRNA northern blot hybridization was performed as described using 32P-labelled in-vitro antisense transcript of full-length Y-Sat or GUS coding sequence that were fragmented with Na2CO3 treatment [10]. mRNA northern blot hybridization was carried out as previously described [39] using the same full-length antisense GUS RNA (unfragmented) as probe.

MUG assay

GUS activities were determined using the kinetic MUG (4-methylumbelliferyl-β - glucuronide) assay according to Chen et al. [39]. GUS activities for Fig. 1B was calculated according to Chen at al. [39], with the Y-axis as pmol MU per min per 5 µg protein. GUS activities for the remaining figures were presented as slope value per 5 µg protein [44].

Nuclear run-on assay

Nuclei were isolated from approximately 4 g of fresh N. tabacum leaves and used for nuclear run-on assay according to the procedure described in Meng and Lemaux [45]. The full-length GUS gene, the elongation factor 1α (EF1α) gene (used as internal reference), and the Fusarium oxysporum FKS1 gene (used as negative control) sequences, were amplified by PCR using the following primers (primer sequences are shown in S2 Table): M13-F and M13-R (from a pGEM-GUS plasmid), EF1α-F and EF1α-R, and FKS1-F and FKS1-R, respectively. The PCR product was separated in 1% agarose gel, denatured, neutralized and then blotted onto Hybond N+ membrane using 20× SSC following the manufacturer's instruction. The membrane was hybridized with the nuclear run-on transcript according to Meng and Lemaux [45] and the hybridizing signals were visualized using a phosphorimager (FLA-5000, Fuji Photo Film).

McrBC digestion PCR

Genomic DNA (∼2 µg) from transgenic 35S-GUS:sSat N. tabacum plants, was mixed with 1×NEB buffer 2, 0.1 µg/µl BSA, 1 mM GTP in 94 µl volume, which was divided in two equal 47 µl aliquots. To one aliquot 3 µl McrBC enzyme (NEB, 10 units/µl) was added, to the other 3 µl of H2O. Both were incubated at 37°C overnight and then diluted with H2O to 100 µl. Four µl was used for each PCR reaction, which was performed using the following cycles: 1 cycle of 95°C for 3 min, 33 cycles of 95°C for 30 sec, 56°C for 45 sec, and 72°C for 90 sec, followed by one cycle of 72°C for 10 min. Sequences of the McrBC PCR primers are listed in S2 Table. Real-time PCR was performed using the Rotor-Gene 6000 (Corbett Life Science, San Francisco, USA) real-time rotary analyser using SYBR Green reagent and Platinum Taq polymerase (Invitrogen) in four technical replicates for each sample.

Bisufite sequencing

Bisulfite conversion of transgenic N. tabacum genomic DNA (∼4 µg) was performed as previously described [33]. The bisulfite-treated DNA was purified using Qiagen PCR Purification kit. Primer design (sequences shown in S2 Table), nested PCR and direct sequencing of PCR products were as previously described [44].

Small RNA sequencing and data analysis

Total RNA was isolated from wild-type Nt-Xanthi plants and SD-CMVΔSat-infected plants using hot-phenol extraction and small RNAs were prepared as described previously [46]. Small RNA library construction and Illumina sequencing was performed by BGI (http://www.genomics.cn/en/index). For data analysis, adapter and low-quality sequences were removed and cleaned reads used for length distribution and subsequent analysis. Overlapping sequences between different libraries were identified using Perl script (http://www.perl.org/). All clean reads were mapped to the uncompleted Nt-Xanthi genome (ftp.sgn.cornel.edu) using SOAP (http://soap.genomics.org.cn/), and all perfectly mapped sequences were used to determine the mapping ratio in different samples.

All clean reads matching to satRNA and control sequences was examined using BLASTN (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) with different E-values (1e−2, 1e−3, 1e−4 and 1e−5) to determine different degrees of similarity. ClustalX (http://www.clustal.org/) was used for sequence alignments and phylogenetic analysis of satRNA genomes.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. SimonAE, RoossinckMJ, HaveldaZ (2004) Plant virus satellite and defective interfering RNAs: new paradigms for a new century. Annu Rev Phytopathol 42 : 415–437.

2. HuC-C, HsuY-H, LinN-S (2009) Satellite RNAs and satellite viruses of plants. Viruses 1 : 1325–1350.

3. RoossinckM, SleatD, PalukaitisP (1992) Satellite RNAs of plant viruses: structures and biological effects. Microbiological Reviews 56 : 265–279.

4. Garcia-Arenal F, Palukaitis P (1999) Structure and functional relationships of satellite RNAs of cucumber mosaic virus. Satellites and Defective Viral RNAs: Springer. pp. 37–63.

5. WangX-B, WuQ, ItoT, CilloF, LiWX, et al. (2010) RNAi-mediated viral immunity requires amplification of virus-derived siRNAs in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107 : 484–489.

6. ChoiSH, SeoJK, KwonSJ, RaoAL (2012) Helper virus-independent transcription and multimerization of a satellite RNA associated with cucumber mosaic virus. J Virol 86 : 4823–4832.

7. ChaturvediS, KalantidisK, RaoAL (2014) A bromodomain-containing host protein mediates the nuclear importation of a satellite RNA of Cucumber mosaic virus. J Virol 88 : 1890–1896.

8. CollmerCW, HowellSH (1992) Role of satellite RNA in the expression of symptoms caused by plant viruses. AnnRev Phytopathol 30 : 419–442.

9. ShimuraH, PantaleoV, IshiharaT, MyojoN, InabaJ-i, et al. (2011) A viral satellite RNA induces yellow symptoms on tobacco by targeting a gene involved in chlorophyll biosynthesis using the RNA silencing machinery. PLoS Pathog 7: e1002021.

10. SmithNA, EamensAL, WangM-B (2011) Viral small interfering RNAs target host genes to mediate disease symptoms in plants. PLoS Pathog 7: e1002022.

11. SimonAE, HowellSH (1986) The virulent satellite RNA of turnip crinkle virus has a major domain homologous to the 3'end of the helper virus genome. The EMBO J 5 : 3423.

12. HajimoradM, GhabrialS, RoossinckM (2009) De novo emergence of a novel satellite RNA of cucumber mosaic virus following serial passages of the virus derived from RNA transcripts. Arch Virol 154 : 137–140.

13. CollmerCW, HadidiA, KaperJ (1985) Nucleotide sequence of the satellite of peanut stunt virus reveals structural homologies with viroids and certain nuclear and mitochondrial introns. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 82 : 3110–3114.

14. MeisterG, TuschlT (2004) Mechanisms of gene silencing by double-stranded RNA. Nature 431 : 343–349.

15. BaulcombeD (2005) RNA silencing. Trends Biochem Sci 30 : 290–293.

16. BaulcombeD (2004) RNA silencing in plants. Nature 431 : 356–363.

17. EamensA, WangM-B, SmithNA, WaterhousePM (2008) RNA silencing in plants: yesterday, today, and tomorrow. Plant Physiol 147 : 456–468.

18. BartelDP (2004) MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell 116 : 281–297.

19. DingS-W, VoinnetO (2007) Antiviral immunity directed by small RNAs. Cell 130 : 413–426.

20. MatzkeMA, BirchlerJA (2005) RNAi-mediated pathways in the nucleus. Nat Rev Genet 6 : 24–35.

21. ZhangH, ZhuJ-K (2011) RNA-directed DNA methylation. Curr Opin Plant Biol 14 : 142–147.

22. WangM-B, WesleySV, FinneganEJ, SmithNA, WaterhousePM (2001) Replicating satellite RNA induces sequence-specific DNA methylation and truncated transcripts in plants. RNA 7 : 16–28.

23. MasutaC, KuwataS, TakanamiY (1988) Effects of extra 5'non-viral bases on the infectivity of transcripts from a cDNA clone of satellite RNA (strain Y) of cucumber mosaic virus. J Biochem 104 : 841–846.

24. ParkYD, PappI, MosconeE, IglesiasV, VaucheretH, et al. (1996) Gene silencing mediated by promoter homology occurs at the level of transcription and results in meiotically heritable alterations in methylation and gene activity. Plant J 9 : 183–194.

25. ClarkSJ, HarrisonJ, PaulCL, FrommerM (1994) High sensitivity mapping of methylated cytosines. Nucleic Acids Res 22 : 2990–2997.

26. LeTN, SchumannU, SmithNA, TiwariS, AuP, et al. (2014) DNA demethylases target promoter transposable elements to positively regulate stress responsive genes in Arabidopsis. Genome Biol 15 : 458.

27. MosherRA, MelnykCW, KellyKA, DunnRM, StudholmeDJ, et al. (2009) Uniparental expression of PolIV-dependent siRNAs in developing endosperm of Arabidopsis. Nature 460 : 283–286.

28. WangH, ZhangX, LiuJ, KibaT, WooJ, et al. (2011) Deep sequencing of small RNAs specifically associated with Arabidopsis AGO1 and AGO4 uncovers new AGO functions. Plant J 67 : 292–304.

29. HouWN, DuanCG, FangRX, ZhouXY, GuoHS (2011) Satellite RNA reduces expression of the 2b suppressor protein resulting in the attenuation of symptoms caused by Cucumber mosaic virus infection. Mol Plant Pathol 12 : 595–605.

30. KasschauKD, FahlgrenN, ChapmanEJ, SullivanCM, CumbieJS, et al. (2007) Genome-wide profiling and analysis of Arabidopsis siRNAs. PLoS Biol 5: e57.

31. WaterhousePM, WangM-B, LoughT (2001) Gene silencing as an adaptive defence against viruses. Nature 411 : 834–842.

32. MatzkeMA, AufsatzW, KannoT, MetteMF, MatzkeAJ (2002) Homology-dependent gene silencing and host defense in plants. Advances in Genetics 46 : 235–275.

33. WangM-B, HelliwellCA, WuL-M, WaterhousePM, PeacockWJ, et al. (2008) Hairpin RNAs derived from RNA polymerase II and polymerase III promoter-directed transgenes are processed differently in plants. RNA 14 : 903–913.

34. DuanC-G, FangY-Y, ZhouB-J, ZhaoJ-H, HouW-N, et al. (2012) Suppression of Arabidopsis ARGONAUTE1-mediated slicing, transgene-induced RNA silencing, and DNA methylation by distinct domains of the Cucumber mosaic virus 2b protein. Plant Cell 24 : 259–274.

35. SteinhauerD, HollandJ (1987) Rapid evolution of RNA viruses. Ann Rev Microbiol 41 : 409–431.

36. HorieM, HondaT, SuzukiY, KobayashiY, DaitoT, et al. (2010) Endogenous non-retroviral RNA virus elements in mammalian genomes. Nature 463 : 84–87.

37. ChibaS, KondoH, TaniA, SaishoD, SakamotoW, et al. (2011) Widespread endogenization of genome sequences of non-retroviral RNA viruses into plant genomes. PLoS Pathog 7: e1002146.

38. GleaveAP (1992) A versatile binary vector system with a T-DNA organisational structure conducive to efficient integration of cloned DNA into the plant genome. Plant Mol Biol 20 : 1203–1207.

39. ChenS, HelliwellCA, WuL-M, DennisES, UpadhyayaNM, et al. (2005) A novel T-DNA vector design for selection of transgenic lines with simple transgene integration and stable transgene expression. Funct Plant Biol 32 : 671–681.

40. CazzonelliCI, VeltenJ (2006) An in vivo, luciferase-based, Agrobacterium-infiltration assay system: implications for post-transcriptional gene silencing. Planta 224 : 582–597.

41. WoodCC, PetrieJR, ShresthaP, MansourMP, NicholsPD, et al. (2009) A leaf-based assay using interchangeable design principles to rapidly assemble multistep recombinant pathways. Plant Biotech J 7 : 914–924.

42. Draper J, Scott R, Armitage P, Walden R (1988) Plant genetic transformation and gene expression: a laboratory manual: Blackwell Scientific Publications.

43. De Vries S, Hoge H, Bisseling T (1989) Isolation of total and polysomal RNA from plant tissues. Plant Molecular Biology Manual: Springer. pp. 323–335.

44. FinnTE, WangL, SmoliloD, SmithNA, WhiteR, et al. (2011) Transgene expression and transgene-induced silencing in diploid and autotetraploid Arabidopsis. Genetics 187 : 409–423.

45. MengL, LemauxP (2003) A simple and rapid method for nuclear run-on transcription assays in plants. Plant Mol Biol Rep 21 : 65–71.

46. HeX-F, FangY-Y, FengL, GuoH-S (2008) Characterization of conserved and novel microRNAs and their targets, including a TuMV-induced TIR–NBS–LRR class R gene-derived novel miRNA in Brassica. FEBS letters 582 : 2445–2452.

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukčná medicína

Článek Phosphorylation of Elp1 by Hrr25 Is Required for Elongator-Dependent tRNA Modification in YeastČlánek Naturally Occurring Differences in CENH3 Affect Chromosome Segregation in Zygotic Mitosis of HybridsČlánek Insight in Genome-Wide Association of Metabolite Quantitative Traits by Exome Sequence AnalysesČlánek ALIX and ESCRT-III Coordinately Control Cytokinetic Abscission during Germline Stem Cell DivisionČlánek Deciphering the Genetic Programme Triggering Timely and Spatially-Regulated Chitin Deposition

Článok vyšiel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Najčítanejšie tento týždeň

2015 Číslo 1- Gynekologové a odborníci na reprodukční medicínu se sejdou na prvním virtuálním summitu

- Je „freeze-all“ pro všechny? Odborníci na fertilitu diskutovali na virtuálním summitu

-

Všetky články tohto čísla

- The Combination of Random Mutagenesis and Sequencing Highlight the Role of Unexpected Genes in an Intractable Organism

- Ataxin-3, DNA Damage Repair, and SCA3 Cerebellar Degeneration: On the Path to Parsimony?

- α-Actinin-3: Why Gene Loss Is an Evolutionary Gain

- Origins of Context-Dependent Gene Repression by Capicua

- Transposable Elements Contribute to Activation of Maize Genes in Response to Abiotic Stress

- No Evidence for Association of Autism with Rare Heterozygous Point Mutations in Contactin-Associated Protein-Like 2 (), or in Other Contactin-Associated Proteins or Contactins

- Nur1 Dephosphorylation Confers Positive Feedback to Mitotic Exit Phosphatase Activation in Budding Yeast

- A Regulatory Hierarchy Controls the Dynamic Transcriptional Response to Extreme Oxidative Stress in Archaea

- Genetic Variants Modulating CRIPTO Serum Levels Identified by Genome-Wide Association Study in Cilento Isolates

- Small RNA Sequences Support a Host Genome Origin of Satellite RNA

- Phosphorylation of Elp1 by Hrr25 Is Required for Elongator-Dependent tRNA Modification in Yeast

- Genetic Mapping of MAPK-Mediated Complex Traits Across

- An AP Endonuclease Functions in Active DNA Demethylation and Gene Imprinting in

- Developmental Regulation of the Origin Recognition Complex

- End of the Beginning: Elongation and Termination Features of Alternative Modes of Chromosomal Replication Initiation in Bacteria

- Naturally Occurring Differences in CENH3 Affect Chromosome Segregation in Zygotic Mitosis of Hybrids

- Imputation of the Rare G84E Mutation and Cancer Risk in a Large Population-Based Cohort

- Polycomb Protein SCML2 Associates with USP7 and Counteracts Histone H2A Ubiquitination in the XY Chromatin during Male Meiosis

- A Genetic Strategy for Probing the Functional Diversity of Magnetosome Formation

- Interactions of Chromatin Context, Binding Site Sequence Content, and Sequence Evolution in Stress-Induced p53 Occupancy and Transactivation

- The Yeast La Related Protein Slf1p Is a Key Activator of Translation during the Oxidative Stress Response

- Integrative Analysis of DNA Methylation and Gene Expression Data Identifies as a Key Regulator of COPD

- Proteasomes, Sir2, and Hxk2 Form an Interconnected Aging Network That Impinges on the AMPK/Snf1-Regulated Transcriptional Repressor Mig1

- Functional Interplay between the 53BP1-Ortholog Rad9 and the Mre11 Complex Regulates Resection, End-Tethering and Repair of a Double-Strand Break

- Estrogenic Exposure Alters the Spermatogonial Stem Cells in the Developing Testis, Permanently Reducing Crossover Levels in the Adult

- Protein Poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation Regulates Immune Gene Expression and Defense Responses

- Sumoylation Influences DNA Break Repair Partly by Increasing the Solubility of a Conserved End Resection Protein

- A Discrete Transition Zone Organizes the Topological and Regulatory Autonomy of the Adjacent and Genes

- Elevated Mutation Rate during Meiosis in

- The Intersection of the Extrinsic Hedgehog and WNT/Wingless Signals with the Intrinsic Hox Code Underpins Branching Pattern and Tube Shape Diversity in the Airways

- MiR-24 Is Required for Hematopoietic Differentiation of Mouse Embryonic Stem Cells

- Tissue-Specific Effects of Genetic and Epigenetic Variation on Gene Regulation and Splicing

- Heterologous Aggregates Promote Prion Appearance via More than One Mechanism

- The Tumor Suppressor BCL7B Functions in the Wnt Signaling Pathway

- , A -Acting Locus that Controls Chromosome-Wide Replication Timing and Stability of Human Chromosome 15

- Regulating Maf1 Expression and Its Expanding Biological Functions

- A Polyubiquitin Chain Reaction: Parkin Recruitment to Damaged Mitochondria

- RecFOR Is Not Required for Pneumococcal Transformation but Together with XerS for Resolution of Chromosome Dimers Frequently Formed in the Process

- An Intracellular Transcriptomic Atlas of the Giant Coenocyte

- Insight in Genome-Wide Association of Metabolite Quantitative Traits by Exome Sequence Analyses

- The Role of the Mammalian DNA End-processing Enzyme Polynucleotide Kinase 3’-Phosphatase in Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 3 Pathogenesis

- The Global Regulatory Architecture of Transcription during the Cell Cycle

- Identification and Functional Characterization of Coding Variants Influencing Glycemic Traits Define an Effector Transcript at the Locus

- Altered Ca Kinetics Associated with α-Actinin-3 Deficiency May Explain Positive Selection for Null Allele in Human Evolution

- Genetic Variation in the Nuclear and Organellar Genomes Modulates Stochastic Variation in the Metabolome, Growth, and Defense

- PRDM9 Drives Evolutionary Erosion of Hotspots in through Haplotype-Specific Initiation of Meiotic Recombination

- Transcriptional Control of an Essential Ribozyme in Reveals an Ancient Evolutionary Divide in Animals

- ALIX and ESCRT-III Coordinately Control Cytokinetic Abscission during Germline Stem Cell Division

- Century-scale Methylome Stability in a Recently Diverged Lineage

- A Re-examination of the Selection of the Sensory Organ Precursor of the Bristle Sensilla of

- Antagonistic Cross-Regulation between Sox9 and Sox10 Controls an Anti-tumorigenic Program in Melanoma

- A Dependent Pool of Phosphatidylinositol 4,5 Bisphosphate (PIP) Is Required for G-Protein Coupled Signal Transduction in Photoreceptors

- Deciphering the Genetic Programme Triggering Timely and Spatially-Regulated Chitin Deposition

- Aberrant Gene Expression in Humans

- Fascin1-Dependent Filopodia are Required for Directional Migration of a Subset of Neural Crest Cells

- The SWI2/SNF2 Chromatin Remodeler BRAHMA Regulates Polycomb Function during Vegetative Development and Directly Activates the Flowering Repressor Gene

- Evolutionary Constraint and Disease Associations of Post-Translational Modification Sites in Human Genomes

- A Truncated NLR Protein, TIR-NBS2, Is Required for Activated Defense Responses in the Mutant

- The Genetic and Mechanistic Basis for Variation in Gene Regulation

- Inactivation of PNKP by Mutant ATXN3 Triggers Apoptosis by Activating the DNA Damage-Response Pathway in SCA3

- DNA Damage Response Factors from Diverse Pathways, Including DNA Crosslink Repair, Mediate Alternative End Joining

- hnRNP K Coordinates Transcriptional Silencing by SETDB1 in Embryonic Stem Cells

- PLOS Genetics

- Archív čísel

- Aktuálne číslo

- Informácie o časopise

Najčítanejšie v tomto čísle- The Global Regulatory Architecture of Transcription during the Cell Cycle

- A Truncated NLR Protein, TIR-NBS2, Is Required for Activated Defense Responses in the Mutant

- Proteasomes, Sir2, and Hxk2 Form an Interconnected Aging Network That Impinges on the AMPK/Snf1-Regulated Transcriptional Repressor Mig1

- The SWI2/SNF2 Chromatin Remodeler BRAHMA Regulates Polycomb Function during Vegetative Development and Directly Activates the Flowering Repressor Gene

Prihlásenie#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zabudnuté hesloZadajte e-mailovú adresu, s ktorou ste vytvárali účet. Budú Vám na ňu zasielané informácie k nastaveniu nového hesla.

- Časopisy