-

Články

- Časopisy

- Kurzy

- Témy

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Competition between Heterochromatic Loci Allows the Abundance of the Silencing Protein, Sir4, to Regulate Assembly of Heterochromatin

Heterochromatin, characterized by the repression of transcription, is a specialized chromatin structure that plays both structural and functional roles on chromosomes. Heterochromatic domains are dynamic, switching between active and inactive states, and this property is used by cells during developmental switches and may generate phenotypic diversity. We have shown that competition between different heterochromatic domains for limiting amounts of a heterochromatin protein, Sir4, plays a critical role in the switch from an active to an inactive state. Previous work has suggested that this switch is regulated by turnover of histone modifications in these regions and our data suggests that modulating Sir4 abundance acts in parallel to these changes to influence the rate of de novo assembly. This work supports a model in which competition between different chromosomal domains is exploited by cells to regulate cell identity.

Published in the journal: Competition between Heterochromatic Loci Allows the Abundance of the Silencing Protein, Sir4, to Regulate Assembly of Heterochromatin. PLoS Genet 11(11): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1005425

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1005425Summary

Heterochromatin, characterized by the repression of transcription, is a specialized chromatin structure that plays both structural and functional roles on chromosomes. Heterochromatic domains are dynamic, switching between active and inactive states, and this property is used by cells during developmental switches and may generate phenotypic diversity. We have shown that competition between different heterochromatic domains for limiting amounts of a heterochromatin protein, Sir4, plays a critical role in the switch from an active to an inactive state. Previous work has suggested that this switch is regulated by turnover of histone modifications in these regions and our data suggests that modulating Sir4 abundance acts in parallel to these changes to influence the rate of de novo assembly. This work supports a model in which competition between different chromosomal domains is exploited by cells to regulate cell identity.

Introduction

Heterochromatin, or silent chromatin, is a specialized chromatin structure that plays structural and functional roles on chromosomes. These silent domains are characterized by repression of transcription and recombination, repressive histone modifications, and epigenetic inheritance [1]. The locations and boundaries of heterochromatic loci are dynamic and changing the landscapes of heterochromatin can cause changes in cell identity.

In the budding yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, heterochromatin is found at the silent mating loci (HMLα and HMRa, or the HM loci), telomeres and the rDNA gene loci. At the HM loci and telomeres, heterochromatin contains hypoacetylated and demethylated nucleosomes that are bound by the SIR (Silent Information Regulator) complex, which consists of three proteins: Sir2, Sir3 and Sir4 [1,2]. Sir2 is the founding member of a conserved family of NAD-dependent protein deacetylases and creates the hypoacetylated domains of nucleosomes within heterochromatin [3–5]. Sir3 and Sir4 are histone-binding proteins that bind with high affinity to deacetylated and demethylated nucleosomes [6–8]. Mutation of any of these three SIR genes abolishes both telomeric and HM silencing [9–14]. Current models for silent chromatin assembly propose that after initial recruitment of the SIR complex to nucleation elements, called silencers, at the HM loci, or to a telomere, iterative rounds of histone deacetylation and SIR complex recruitment lead to the spreading of the SIR complex [15–17]. After SIR complex spreading, recent work has suggested a final maturation step that requires the demethylation of K79 on histone H3, which is needed to form functional silent chromatin and trigger transcriptional repression [18–20].

The de novo assembly of heterochromatin is best understood in budding yeast where there is a block to assembly in G1 phase, and where assembly requires passage through S phase and dissolution of sister chromatid cohesion [21–23]. The S-phase requirement does not depend on DNA replication, but instead depends on some other event that occurs during S phase [24,25]. Current models propose that this cell cycle dependence reflects a cell cycle dependent removal of both histone modifications and the histone H2A variant, Htz1, which are refractory to heterochromatin assembly, and most cells take two cell cycles to fully silence a new site [19,26–28]. Methylation on K4 or K79 of histone H3, catalyzed by the Set1 and Dot1 methyltransferases respectively, inhibit heterochromatin assembly [29–33] and de novo assembly of heterochromatin occurs faster in dot1Δ or set1Δ mutants, supporting the model that these modifications must be removed before a new site of heterochromatin can assemble [19,26,34]. To date, however, there is no evidence indicating that methylation in heterochromatic regions is removed at specific points in the cell cycle.

Although changes in histone modifications are thought to regulate de novo assembly of silent chromatin, past work proposed that Sir4 may also play a role in regulating establishment. Silencing is sensitive to the dosage of Sir4: cells containing additional SIR4 have improved silencing and heterozygous SIR4/sir4Δ diploids de-repress a weakened HMR locus [35]. These data led to the idea that the abundance of Sir4 may regulate the establishment of silencing, but the assays employed in these studies were not able to differentiate between defects in the establishment, maintenance, or stability of heterochromatin, and there is currently no evidence that Sir4 protein levels fluctuate.

We observed that Sir4 levels fall precipitously during a prolonged G1 arrest, and upon release from this arrest, Sir4 protein levels recover after two cell cycles, similar to the time required for de novo establishment of heterochromatin [19,21,26]. We therefore revisited the question of whether Sir4 dosage regulates de novo establishment using a single cell silencing establishment assay that monitors HMLα repression directly [26]. We find that increasing Sir4 abundance speeds, and decreasing Sir4 abundance slows, the de novo establishment of heterochromatin. ubp10Δ and yku70Δ mutants, like dot1Δ, also speed de novo establishment as well as disrupt telomeric silencing. To investigate the relationship between DOT1, UBP10, YKU70 and SIR4, we examined the speed of de novo establishment in dot1Δ, ubp10Δ and yku70 mutants in conditions that lower Sir4 protein levels or that suppress their telomeric silencing defects. We conclude that UBP10 and YKU70 indirectly influence establishment by liberating Sir4 from telomeres, while DOT1 acts directly at HMLα, and propose a model in which the competition between telomeres and HMLα allows limiting Sir4 levels to regulate de novo establishment.

Results

Sir4 protein decreases during a G1 arrest

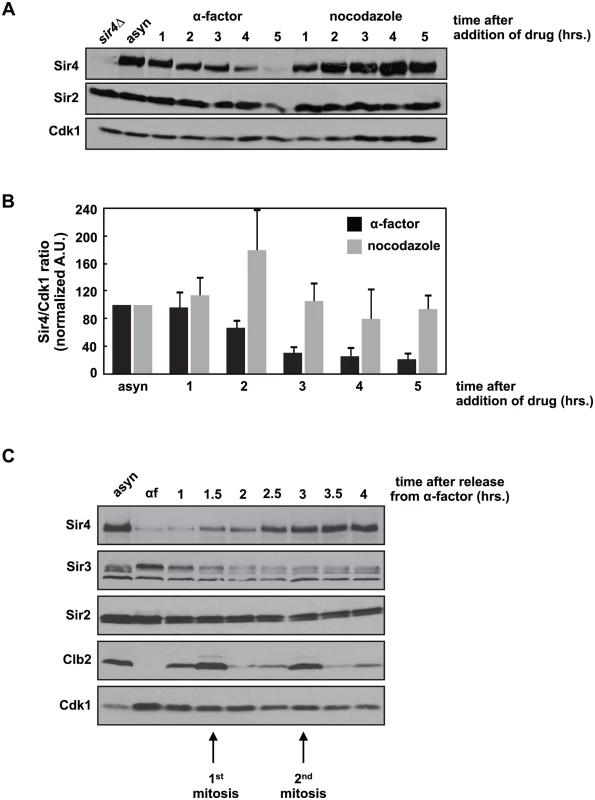

We were interested in whether Sir4 protein levels fluctuate during the cell cycle and observed that during a prolonged G1 arrest induced by the mating pheromone, alpha factor, Sir4 levels fell precipitously (Fig 1A). This decrease is not simply caused by cell cycle arrest, as cells arrested in mitosis with nocodazole maintain Sir4 levels (Fig 1A). Quantification of this experiment shows that Sir4 levels fall four - to five-fold after five hours of growth in alpha factor, but remain unchanged in nocodazole (Fig 1B). When pheromone-arrested cells are released back into the cell cycle, Sir4 protein levels recover after two cell cycles (Fig 1C). We also observed a similar drop in Sir4 protein levels when cells are arrested in stationary phase by prolonged growth in raffinose, a poor carbon source (S1A Fig). Re-feeding with dextrose allowed cells to re-enter the cell cycle and Sir4 levels recover after six hours.

Fig. 1. Sir4 protein is degraded during a prolonged arrest in G1 and takes two cell cycles to recover after release from the arrest.

(A) Asynchronously growing (asyn) wild type (ADR4006) cells were arrested in G1 with 1μg/ml α-factor or arrested in mitosis with 10μg/ml nocodazole at 25°C. Samples were harvested every hour and protein levels were analyzed by western blot. Cdk1 is shown as a loading control. (B) Samples prepared as in (A) were quantified and the average amount of Sir4 (+/- SEM) relative to Cdk1 levels, normalized to the asynchronous (asyn) sample (which was arbitrarily set to 100), of three independent experiments is shown. (C) Asynchronously growing (asyn) wild type (ADR4006) cells were arrested in 1μg/ml α-factor for five hours (αf) and released from the arrest into fresh media at 25°C. Samples were harvested every 30 minutes and protein levels were analyzed by western blot. Cdk1 is shown as a loading control, and the mitotic cyclin, Clb2, is used as a marker of mitosis. This dramatic decrease in Sir4 abundance during a pheromone arrest has not been reported previously, and is paradoxical: Sir4, and the entire SIR complex, is required to maintain mating type identity, and mating type identity is needed to maintain a pheromone arrest. Sir4 localization by ChIP to a HMLα silencer (HML-E) and TELVI-R, however, is not significantly different in cells arrested in G1 by pheromone, in mitosis by nocodazole, or grown asynchronously, confirming that existing sites of heterochromatin are maintained despite falling Sir4 protein levels (S1B Fig). In addition, the average intensity of intra-nuclear Sir4-GFP foci, which have previously been shown to mark clusters of telomeres and HM loci [36,37], are similar between cells arrested in G1 and mitosis (S1C and S1D Fig). Finally, most Sir4 is present on chromatin, and although there is less Sir4 in pheromone arrested cells, the ratio of chromatin to soluble Sir4 is similar in pheromone and nocodazole arrested cells (S1E Fig).

SIR4 is haploinsufficient for de novo establishment of silencing

Sir4 protein re-accumulates in two cell cycles after release from G1 arrest (Fig 1C). Previous reports have described similar timing for the establishment of de novo silencing [19,21,22,26], so we considered the possibility that Sir4 abundance may play a role regulating de novo establishment.

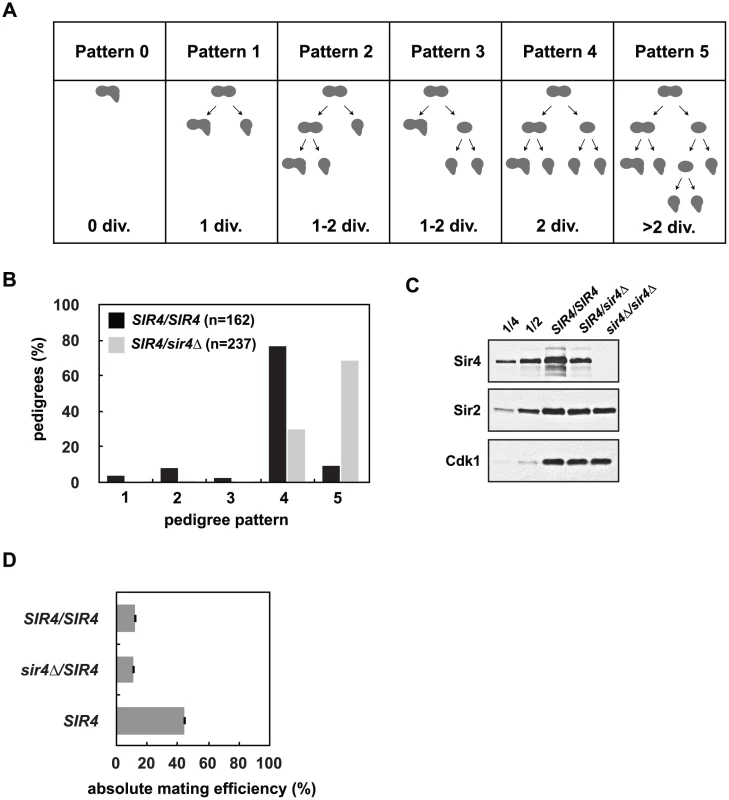

Previous work has shown that SIR4 is haploinsufficient for silencing at a weakened and modified HMRa (hmrΔA::ADE2) [35], and we see a similar defect at a telomere proximal URA3 reporter gene (TELVII-L-URA3) in SIR4/sir4Δ heterozygotes (S2A Fig). We wanted to determine whether this haploinsufficiency is caused by a defect in establishment or stability of heterochromatin, so we utilized a single cell silencing establishment assay in which two engineered strains are mated and the assembly of heterochromatin at HMLα is monitored in the resulting zygote and its progeny (see [26] and Fig 2A for additional details). The diploid cells initially behave phenotypically as MATα cells, but upon silencing of HMLα they switch identity and behave as MATa cells. This switch is monitored by the response of the diploids and their progeny to exogenous mating pheromone, which causes cell cycle arrest and polarization in cells that silence HMLα. The number of cell divisions required for silencing establishment is determined by pedigree analysis (Fig 2A).

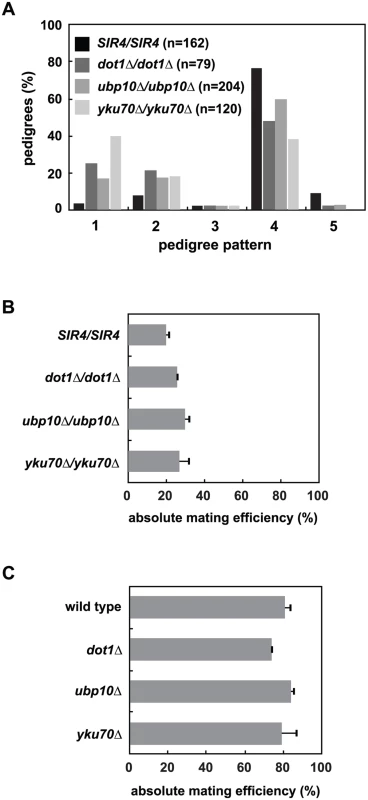

Fig. 2. Reduced Sir4 abundance causes delays in de novo establishment of heterochromatin.

(A) De novo establishment was monitored in a single cell establishment assay as described in Osborne et al. [26]. Specialized mating strains (JRY8828 and JRY8829) are mated and the behavior of the zygote and its progeny are grown adjacent to a large patch of MATα cells (ADR22) and their response is monitored in a pedigree assay. JRY8828 has no mating information and will mate as an MATa cell. JRY8829, which has an intact HMLα, but is also sir3Δ, will de-repress HMLα and mate as an α cell. Immediately after mating the zygote will continue to mate as an MATα cell because no other mating information is present. The zygote, however, is SIR3/sir3Δ and as soon as HMLα is repressed, the zygote and its progeny will behave as a MATa cell and respond to α-factor pheromone which causes cell cycle arrest and the formation of a mating projection. The behavior of the zygote and its progeny are grouped into six pedigree patterns. Pattern 0 denotes a pedigree that silence HMLα without dividing, Pattern 1 silence after one division, Pattern 4 after two divisions, and in Patterns 2 and 3 silencing is asymmetric—either the mother or first daughter silence after two divisions. Pattern 5 encompasses all pedigrees that silence after more than two divisions, including those that contain cells that don’t silence within the experiment. (B) Haploid cells that were either SIR4 or sir4Δ were mated to form SIR4/SIR4 (JRY8828 X JRY8829) and sir4Δ/SIR4 (ADR4592 X JRY8829 or JRY8828 X ADR4593, see S2B Fig) diploid zygotes and were monitored for establishment of silencing at HMLα and categorized as in (A). The effect of halving the Sir4 levels is significant (p<0.0000001, by the likelihood ratio test). (C) SIR4/SIR4 (JRY8828 X JRY8829), sir4Δ/SIR4 (ADR4592 X JRY8829), and sir4Δ/sir4Δ (ADR4592 X ADR4593) cells were grown at 25°C, harvested and analyzed by western blot. Two-fold serial dilutions of the SIR4/SIR4 sample was analyzed to assess Sir4 concentration. (D) Quantitative mating assays were performed by crossing diploid strains from (B) and a wild type MATa strain (ADR21) to a MATα tester strain (ADR3082). The absolute mating efficiency is the proportion of cells of each query strain that mated and formed colonies on synthetic media lacking amino acids. There is no statistical significance between the mating efficiencies of SIR4/SIR4 and sir4Δ/SIR4 cells (Student’s two tailed t-test). In this assay, approximately 80% of SIR4/SIR4 homozygotes establish silencing at HMLα in two cell cycles ([26] and Fig 2B). sir4Δ/SIR4 heterozygotes, however, establish silencing at HMLα significantly more slowly (Fig 2B). Heterozygous sir4Δ/SIR4 cells contain approximately half the amount of Sir4 as homozygous SIR4/SIR4 cells (Fig 2C) and the establishment defect is independent of which strain is deleted for SIR4 (S2B Fig). Once HMLα is silenced (and the diploid zygotes mate as MATa cells), there is no significant difference in the mating efficiency of SIR4/sir4Δ versus SIR4/SIR4 diploids (Fig 2D) indicating the defect in sir4Δ/SIR4 cells is specific to silent chromatin establishment and not long-term stability. The pseudo-haploid diploids, however, mate with 3-fold lower efficiency than control haploid MATa cells (Fig 2D), perhaps due to an increase in size and ploidy compared to the control haploid cells.

Increasing Sir4 levels speed de novo heterochromatin assembly

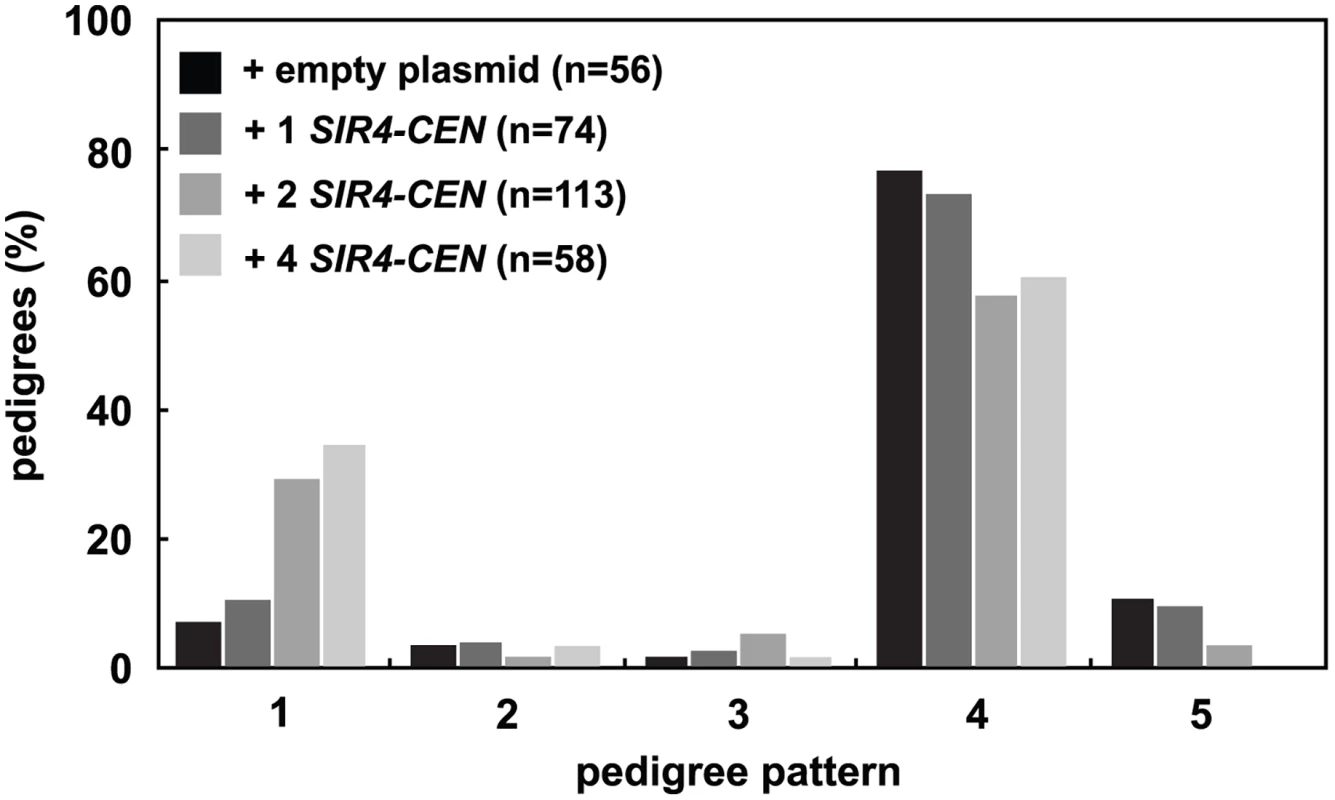

Because a decrease in the levels of Sir4 slows silent chromatin establishment, we wondered if increasing the concentration of Sir4 would speed establishment. Past work has shown that increasing Sir4 levels can improve silencing ([35] and S3A Fig), but has not distinguished whether this improvement is caused by improved stability or changes in the efficiency of establishment. Selection of one, two or four low-copy centromeric plasmids containing SIR4 in zygotes increased the amount of Sir4 protein in these cells (S3B Fig) and significantly increased the speed of establishment in the single cell assay (Fig 3). These changes are not caused by the selection for multiple plasmids, as the presence of two or four empty plasmids does not change the speed of establishment as compared to cells containing no plasmids (S3C Fig).

Fig. 3. Increasing Sir4 speeds de novo establishment.

One or two centromeric plasmids, each containing SIR4 (pAR646 and pAR722), were transformed into one or both mating strains (JRY8828 and JRY8829) prior to mating. The empty plasmid control represents one empty centromeric plasmid in each strain (pRS313 or pRS316, and see S3C Fig). Cells were mated and the resulting zygotes were monitored and categorized as in Fig 2A. Addition of 2 SIR4-CEN plasmids or 4 SIR4-CEN plasmids were each significantly different from the empty plasmid distribution (p = 0.002 and p = 0.0004, respectively, by the likelihood ratio test). Statistics for every pairwise comparison can be found in S1 Table. Since the copy number of centromeric plasmids is variable in cells, we tested if other methods of increasing Sir4 would also improve silencing establishment. We created cells that contain SIR4 driven by a galactose inducible promoter (GAL-SIR4) and constitutively express an estrogen receptor-Gal4 DNA binding domain fusion protein (ER-GAL4-bd) which allows graded expression of Sir4 using varying estradiol concentrations, rather than induction with galactose [38] (S3D Fig). The speed of silencing establishment in cells with increased Sir4 expression is increased, in a manner similar to that seen with the addition of the SIR4-CEN plasmids (S3E Fig).

Further increasing Sir4 levels, however, is detrimental to the establishment of silencing. High copy 2μ-SIR4 plasmids and strong overexpression of SIR4 from a galactose inducible promoter (using galactose rather than estradiol) blocks or slows establishment, and causes derepression of both a telomeric URA3 reporter and a weakened and modified HMRa (hmrΔE::TRP1) (S4 Fig). These findings are consistent with past data showing overabundance of Sir4 in cells disrupts silent chromatin by preventing assembly of a complete SIR complex [39–41].

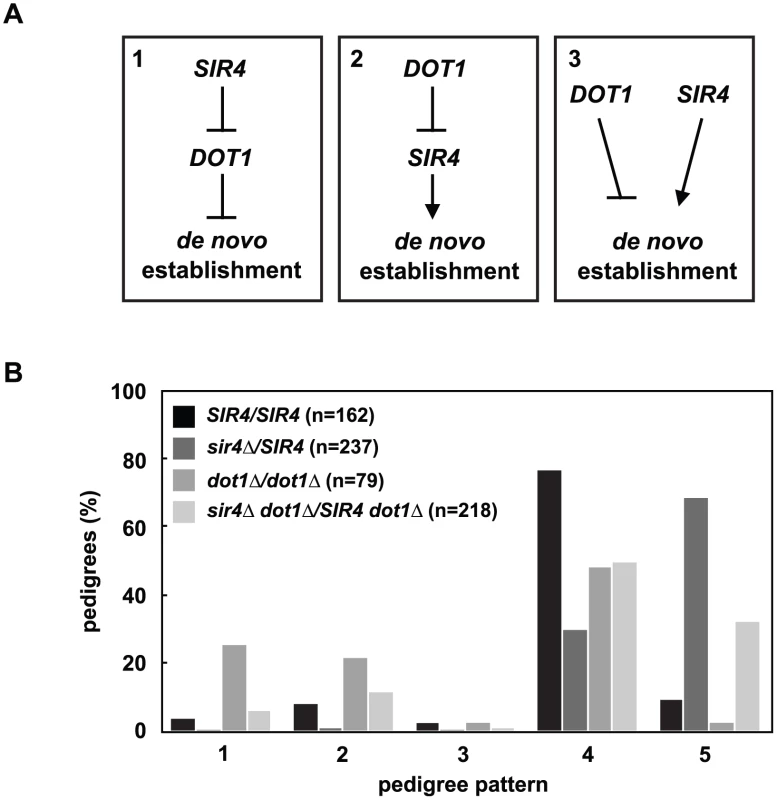

Epistasis analysis of dot1Δ and SIR4/sir4Δ

Deletion of DOT1, the histone H3 K79 methyltransferase, has also been shown to speed the de novo establishment of silent chromatin [19,26,34], which led to the proposal that the removal of histone H3 K79 methylation at silent loci may be a regulated step in de novo assembly. The effect of increasing Sir4 levels is similar to deleting DOT1, so we wondered if changes in Sir4 abundance acted upstream, downstream or independently of DOT1 function (Fig 4A).

Fig. 4. DOT1 acts upstream or independently of Sir4 abundance.

(A) DOT1 and SIR4 could regulate de novo establishment in one of three ways: Model 1) SIR4 inhibits DOT1, and DOT1 inhibits de novo establishment, model 2) DOT1 inhibits SIR4, and SIR4 promotes de novo establishment, and model 3) DOT1 and SIR4 function in separate pathways to regulate de novo establishment. (B) Cells were mated to create SIR4/SIR4 (JRY8828 X JRY8829), sir4Δ/SIR4 (ADR4592 X JRY8829), dot1Δ/dot1Δ (ADR4631 X ADR4632), and sir4Δ dot1Δ/SIR4 dot1Δ (ADR4631 X ADR5607 or ADR5640 X ADR4632), and the resulting zygotes were monitored and categorized as in Fig 2A. The dot1Δ/dot1Δ distribution is significantly different from the sir4Δ dot1Δ/SIR4 dot1 and the sir4Δ/SIR4 distributions (p<0.0000001 and p<0.0000001, respectively, by the likelihood ratio test). Statistics for every pairwise comparison can be found in S1 Table. To test these three models we monitored silencing establishment in dot1Δ SIR4/dot1Δ sir4Δ diploids (Fig 4B). If Dot1 functions downstream of Sir4 abundance (Fig 4A, Model 1) then dot1Δ SIR4/dot1Δ sir4Δ diploids should be indistinguishable from dot1Δ/dot1Δ diploids. These diploids, however, are defective in the establishment of silent chromatin compared to SIR4/SIR4 cells, although to a lesser extent than SIR4/sir4Δ cells. This result clearly rules out Model 1, in which Sir4 abundance functions upstream of Dot1, but this result alone cannot distinguish between the two remaining models (Fig 4A, Models 2 and 3).

Deletion of UBP10 and YKU70 disrupt telomeric silencing and cause earlier establishment at HMLα

In order to distinguish between the two remaining models (Fig 4A) we first considered how Dot1, a histone modifying enzyme, might act upstream of Sir4 abundance. Although the positive effect of dot1Δ on silencing establishment has been proposed to reflect changes in chromatin state at the HM loci [19,26], dot1Δ cells are also defective for subtelomeric silencing ([32,33] and S5A Fig), and this phenotype might indirectly affect the HM loci. Past studies have shown that telomeres and the HM loci compete for silencing proteins [42,43], and that loss of telomeric silencing can have indirect effects on other phenotypes due to re-localization of silencing proteins [44,45].

Mutation of UBP10, a ubiquitin protease that targets K123 on histone H2B, allowed us to examine these two possible functions of Dot1 in silencing establishment. Unlike dot1Δ cells, deletion of UBP10 increases Dot1-dependent K79 and Set1-dependent K4 methylation on histone H3 by increasing K123 ubiquitination on histone H2B ([46,47] and S6 Fig). However, similar to dot1Δ cells, ubp10Δ cells exhibit subtelomeric silencing defects detectable in strains containing a telomeric URA3 reporter ([48] and S5A Fig). Interestingly, we also find that ubp10Δ/ubp10Δ cells, like dot1Δ/dot1Δ cells, speed the rate of establishment (Fig 5A).

Fig. 5. Mutation of UBP10 and YKU70 accelerate de novo establishment of heterochromatin.

(A) SIR4 (JRY8828 and JRY8829), dot1Δ (ADR4631 and ADR4632), ubp10Δ (ADR5087 and ADR5088) or yku70Δ (ADR5841 and ADR5842) cells were mated to produce homozygous zygotes that were monitored and categorized as in Fig 2A. dot1Δ/dot1Δ distribution is similar to experiments published by Osborne et al. [26]. All homozygous deletions are significantly different from the SIR4/SIR4 control (p<0.0000001, by the likelihood ratio test). (B) Resultant diploids from (A) were mated to a MATα tester strain (ADR3082) to determine their mating efficiency. The absolute mating efficiency is the proportion of cells of each query strain that mated and formed colonies on synthetic media lacking amino acids. The average and SEM of at least three independent matings are graphed. There is no statistical significance between the mating efficiencies of the four strains (Student’s two tailed t-test). (C) Haploid MATα wild type (ADR22), dot1Δ (ADR6181), ubp10Δ (ADR6182) and yku70Δ (ADR6183) were mated to a MATa tester strain (ADR3081) to determine their mating efficiency. The average and SEM of at least three independent matings are graphed. There is no statistical significance between the mating efficiencies of the four strains (Student’s two tailed t-test). To further test if loss of subtelomeric silencing could cause an earlier establishment phenotype at HMLα, we deleted YKU70, a component of the Ku complex that is required for non-homologous end joining, normal telomere length maintenance and telomeric silencing [49,50], but is not required for silencing of the native HM loci (Fig 5B and 5C and [51–53]). Like dot1Δ/dot1Δ cells, yku70Δ/yku70Δ cells show a dramatic increase in the speed of silencing establishment (Fig 5A). Deletion of YKU70, UBP10 or DOT1 are specific to silencing establishment because the respective homozygous mutants have no effect on the long-term stability of HMLα silencing in pseudo-MATa diploids (Fig 5B) or HMRa silencing in MATα haploids (Fig 5C), similar to the SIR4/sir4Δ heterozygote (Fig 2D). Deletion of UBP10 or YKU70 also has no significant effect on K79 methylation of histone H3 at HMLα relative to wild type cells ([46,47] and S6 Fig), demonstrating their effect on de novo silencing establishment is not due to inhibition of Dot1.

Like dot1Δ/dot1Δ cells, removing one copy of SIR4 in ubp10Δ/ubp10Δ or yku70Δ/yku70Δ cells slows the speed of establishment compared to SIR4/SIR4 cells (S7A and S7B Fig), which resembles the phenotype of a SIR4/sir4Δ heterozygote. This supports the hypothesis that all three of these proteins may speed de novo establishment indirectly by derepressing subtelomeric silencing. Double mutant diploids that combine dot1Δ, ubp10Δ and yku70Δ were also tested for epistatic effects using the single cell establishment assay. None of the pairwise deletions further increased the speed of establishment compared to the more penetrant single mutant within the pair (S7C–S7E Fig).

Deletion of RIF1 and RIF2 suppress telomeric silencing defects in yku70Δ, dot1Δ and ubp10Δ, but have differing effects on the rate of de novo establishment

Deletion of the telomere binding proteins RIF1 and RIF2 suppress the subtelomeric silencing defect in yku70Δ cells ([54] and S5B Fig). This suppression allowed us to test if the advanced de novo establishment phenotype of yku70Δ cells at HMLα depends on their subtelomeric silencing defect. We find that rif1Δ/rif1Δ and rif1Δ rif2Δ/rif1Δ rif2Δ mutants also suppress the earlier silencing establishment phenotype of yku70Δ/yku70Δ (Fig 6A and S7E Fig), supporting a model whereby effects on telomeric silencing in yku70Δ cells indirectly modulate the speed of silencing establishment at HMLα and act upstream of Sir4 availability (Fig 4A, Model 2).

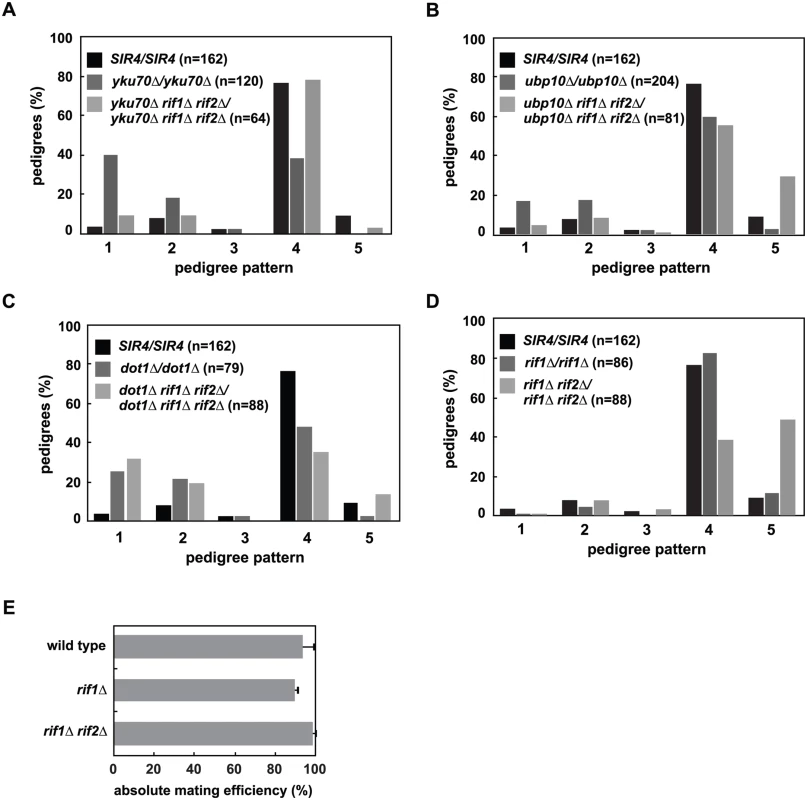

Fig. 6. Mutation of RIF1 and RIF2 define two independent rate limiting steps in de novo establishment of heterochromatin.

(A) SIR4 (JRY8828 and JRY8829), yku70Δ (ADR5841 and ADR5842), yku70Δ rif1Δ rif2Δ (ADR7986 and ADR7989), or rif1Δ (ADR7962 and ADR7966) cells were mated to produce homozygous zygotes that were monitored and categorized as in Fig 2A. The distribution of yku70Δ rif1Δ rif2Δ/yku70Δ rif1Δ rif2Δ and SIR4/SIR4 diploids are similar and yku70Δ/yku70Δ is significantly different from yku70Δ rif1Δ rif2Δ/yku70Δ rif1Δ rif2Δ diploids (p<0.0000001, by the likelihood ratio test). Statistics for every pairwise comparison of A-D can be found in S1 Table. (B) SIR4 (JRY8828 and JRY8829), ubp10Δ (ADR5087 and ADR5088), and ubp10Δ rif1Δ rif2Δ (ADR8922 and ADR8888) were mated to produce homozygous zygotes that were monitored and categorized as in Fig 2A. The distribution of ubp10Δ rif1Δ rif2Δ/ubp10Δ rif1Δ rif2Δ and SIR4/SIR4 diploids are similar and ubp10Δ/ubp10Δ is significantly different from ubp10Δ rif1Δ rif2Δ/ubp10Δ rif1Δ rif2Δ diploids (p = 0.00006, by the likelihood ratio test). (C) SIR4 (JRY8828 and JRY8829), dot1Δ (ADR4631 and ADR4632), and dot1Δ rif1Δ rif2Δ (ADR8916 and ADR8913) cells were mated to produce homozygous zygotes that were monitored and categorized as in Fig 2A. The distribution of dot1Δ/dot1Δ and dot1Δ rif1Δ rif2Δ/dot1Δ rif1Δ rif2Δ and SIR4/SIR4 diploids are similar and SIR4/SIR4 is significantly different from dot1Δ rif1Δ rif2Δ/dot1Δ rif1Δ rif2Δ diploids (p<0.0000001, by the likelihood ratio test). (D) SIR4 (JRY8828 and JRY8829), rif1Δ (ADR7962 and ADR7966), and rif1Δ rif2Δ (ADR9190 and ADR9196) cells were mated to produce homozygous zygotes that were monitored and categorized as in Fig 2A. The distribution of SIR4/SIR4 and rif1Δ/rif1Δ cells are not significantly different from one another, and both are significantly different from rif1Δ rif2Δ/rif1Δ rif2Δ diploids (p<0.0000001, by the likelihood ratio test). (E) Haploid MATα wild type (ADR22), rif1Δ (ADR8824), and rif1Δ rif2Δ (ADR8833) were mated to a MATa tester strain (ADR3081) to determine their mating efficiency. The average and SEM of at least three independent matings are graphed. There is no statistical significance between the mating efficiencies of the three strains (Student’s two tailed t-test). We also find that deletion of RIF1 and RIF2 suppress the telomeric silencing defects of dot1Δ and ubp10Δ cells (S5B Fig), allowing us to rigorously test whether there is a correlation between the speed of silencing establishment at HMLα and the strength of subtelomeric silencing. As in yku70Δ/yku70Δ cells, rif1Δ rif2Δ/rif1Δ rif2Δ cells also suppress the earlier silencing establishment phenotype of ubp10Δ/ubp10Δ cells (Fig 6B). This suppression, however, is not seen in dot1Δ/dot1Δ cells (Fig 6C), despite the complete rescue of subtelomeric silencing in rif1Δ rif2Δ dot1Δ cells (S5B Fig), suggesting two distinct pathways operate to regulate de novo establishment of heterochromatin.

rif1Δ rif2Δ cells have extremely long telomeres which recruit large amounts of the telomere binding protein Rap1 [43,55,56]. Rap1, which also binds at the silencer elements of HMR and HML, binds to both Sir4 and Sir3, and is required for the nucleation of silent chromatin [57–60]. The increased recruitment of Rap1 to telomeres in rif1Δ rif2Δ cells has been speculated to cause the loss of silencing at weakened hmr silencers ([43,55] and S5B Fig), suggesting that the suppression of the subtelomeric silencing defects of dot1Δ, ubp10Δ and yku70Δ cells is also caused by increased recruitment of Sir4 and Sir3 to telomeres. Consistent with this model and our hypothesis that the release of subtelomeric Sir4 speeds de novo establishment in yku70Δ/yku70Δ and ubp10Δ/ubp10Δ cells, we find that rif1Δ rif2Δ/rif1Δ rif2Δ cells have the opposite phenotype and slow the de novo establishment of silencing in a manner similar to that of SIR4/sir4Δ cells (Fig 6D). Like SIR4/sir4Δ cells (Fig 2D), rif1Δ and rif1Δ rif2Δ MATα haploids have similar mating efficiency as wild type cells (Fig 6E), indicating that once silencing is established at HMLα, these mutants have no defects in maintaining the silent state.

Discussion

Changes in Sir4 abundance regulate de novo assembly of silent chromatin

We observed that Sir4 protein levels fall during a prolonged arrest in G1 and re-accumulate over two cell cycles after release from this arrest (Fig 1). This is the first report of cell cycle-dependent changes in Sir protein abundance, and prompted us to directly test if Sir4 abundance modulates the de novo assembly of silent chromatin. Using a single cell establishment assay we have shown that decreasing Sir4 dosage in a SIR4/sir4Δ heterozygote slows de novo assembly at HMLα (Fig 2), and increasing Sir4 dosage speeds assembly (Fig 3). Importantly, the phenotype of SIR4/sir4Δ cells is specific to establishment, as a quantitative mating assay shows that there is no defect in the long-term stability of silencing at HMLα (Fig 2B). These results suggest that in the single-cell pedigree assay the accumulation of Sir4 is a rate-limiting step in silencing establishment.

The original experiments that suggested Sir4 dosage might regulate establishment used an ADE2 reporter placed at a weakened and modified HMRa locus (hmrΔA-ADE2) and monitored repression and/or activation of ADE2 by red/white colony sectoring [35]. Although this assay was proposed to monitor establishment of silent chromatin, changes in sectoring may also monitor the maintenance or stability of heterochromatin. We tested if this sectoring assay could be used as a simpler alternative to the single-cell pedigree assay, and found that dot1Δ and yku70Δ cells, which speed establishment in the pedigree assay (Fig 5A), derepress ADE2 (S5A Fig). Thus, in the context of a weakened silencer at HMR, these mutants negatively impact silencing. We conclude that although experiments using hmrΔA::ADE2 strains identified Sir4 as a dose-dependent regulator of silencing [35], this assay may not always reflect changes in de novo establishment.

Sir4 abundance acts in parallel to changes in histone H3 K79 methylation

Past studies have shown that removal of histone H3 K4 and K79 methylation, and of Htz1-containing nucleosomes, which are all refractory to heterochromatin assembly, is rate-limiting for de novo silencing establishment [19,26–28,34]. We therefore wondered whether Dot1-dependent histone H3 K79 methylation acted in the same pathway as SIR4, or in an independent pathway.

The epistasis analysis between dot1Δ/dot1Δ and SIR4/sir4Δ cells clearly demonstrates that DOT1 inhibition of establishment is not downstream of the effects of changes in Sir4 abundance (Fig 4A and 4B, Model 1). Our finding that yku70Δ/yku70Δ and ubp10Δ/ubp10Δ cells also speed establishment (Fig 5A) suggested a model whereby the loss of subtelomeric heterochromatin common to the dot1Δ, yku70Δ and ubp10Δ mutants [32,33,41,49] may indirectly cause faster establishment of silencing at HMLα.

Loss of one copy of SIR4 in all three mutants causes an intermediate phenotype between SIR4/SIR4 and SIR4/sir4Δ (Fig 4B and S7A and S7B Fig), so these experiments cannot differentiate between a model that these genes act upstream or independently of Sir4 abundance (Fig 4A, Models 2 and 3). An intermediate phenotype might be expected if these genes acted independently of Sir4 abundance. Similarly, because SIR4/sir4Δ is not a null mutant and still contains Sir4, some suppression of the SIR4/sir4Δ phenotype might be expected if these genes acted upstream of Sir4 abundance, and when mutated liberated Sir4 from telomeres.

Our analysis of how deletion of RIF1 and RIF2 interacts with these three mutants significantly clarified our conclusions and suggests that DOT1 and Sir4 abundance function in independent pathways to regulate de novo establishment. Although rif1Δ rif2Δ cells suppress the subtelomeric silencing defects of yku70Δ, ubp10Δ and dot1Δ cells (S5B Fig and [54]), the earlier establishment phenotype is only rescued in rif1Δ rif2Δ yku70Δ/rif1Δ rif2Δ yku70Δ and rif1Δ rif2Δ ubp10Δ/rif1Δ rif2Δ ubp10Δ cells (Fig 6A and 6B). In contrast, rif1Δ rif2Δ dot1Δ/rif1Δ rif2Δ dot1Δ cells, like dot1Δ/dot1Δ cells, establish heterochromatin faster than wild type cells. These differences suggest that DOT1 functions in a distinct pathway from YKU70 and UBP10 (Fig 7).

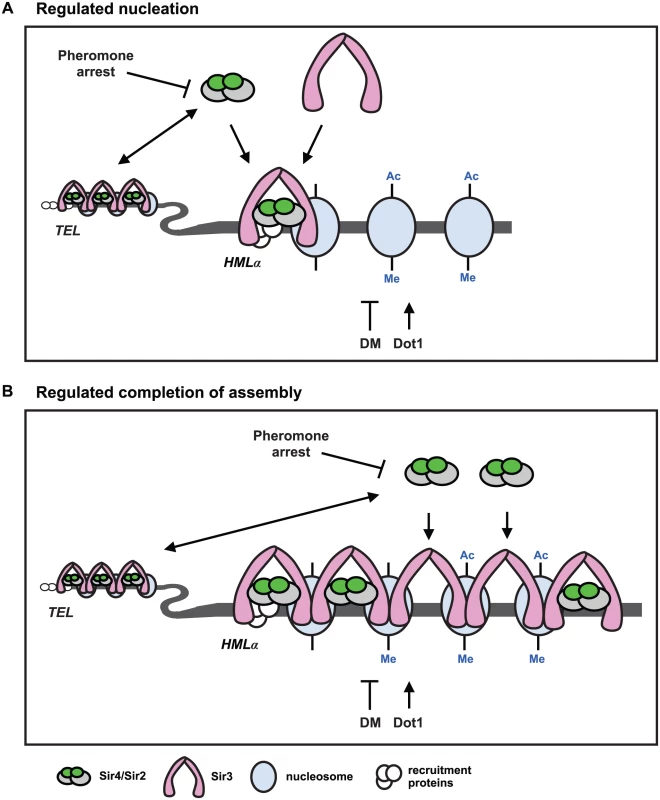

Fig. 7. Two models for de novo establishment of heterochromatin.

(A) Regulated nucleation. Changes in Sir4 availability and demethylation of histone H3 regulate nucleation of heterochromatin. The abundance and availability of Sir4 is downregulated during pheromone arrest, and telomeres and HMLα compete for the available Sir4. When Sir4 is present in extra copies, or is released from telomeres in ubp10Δ or yku70Δ mutants, nucleation occurs faster. If the available Sir4 is reduced in heterozygous SIR4/sir4Δ cells or in rif1Δ rif2Δ cells, that improve telomeric recruitment of Sir4, nucleation slows. These data suggest that recruitment of Sir4 to the HMLα silencer is rate limiting for de novo establishment of heterochromatin. Sir4/Sir2 recruitment leads to deacetylation (Ac) of proximal nucleosomes by Sir2, and promotes the recruitment of Sir3 which interacts with the deacetylated N-terminal tails of histone H4. Dot1 adds, and demethylation (DM) removes, methylation (Me) on lysine 79 of histone H3. Demethylation (DM) may occur enzymatically by an unidentified demethylase, by histone exchange, or by deposition of unmethylated histones after DNA replication. Sir3 interacts specifically with unmethylated histone H3, so removal of K79 methylation also promotes Sir3 binding to nucleosomes, and at silencer elements, both deacetylation and demethylation may be required for nucleation of heterochromatin. In dot1Δ mutants, that have no K79 methylation, de novo establishment occurs faster and suggests demethylation of K79 and subsequent recruitment of Sir3 can also be rate limiting for de novo establishment of heterochromatin. Coincident recruitment of Sir3 and Sir4, and their interaction, is required for efficient de novo establishment. (B) Regulated completion of assembly. Changes in Sir4 availability and demethylation of histone H3 regulate transcriptional repression. Kirchamaier and Rine [20] observed a rate limiting step in de novo establishment after spreading of Sir proteins at HMRa, and Katan-Khaykovich and Struhl [19] showed demethylation of K79 on histone H3 is a slow step in de novo establishment. If the abundance of Sir4 acted at a late step in establishment at HMLα, it would suggest that Sir4 occupancy and histone deacetylation may be incomplete in heterochromatin prior to demethylation of histone H3. Recruitment of Sir4 into silent chromatin would allow complete histone deacetylation and be mechanistically linked to histone demethylation and transcriptional repression. A model for de novo establishment

Our data argue that either increased Sir4 or the absence of histone H3 K79 methylation speeds de novo establishment of heterochromatin. These two events could regulate a common step in heterochromatin assembly, or function independently of each other. Because we see similar phenotypes in cells with increased Sir4 as with mutation of DOT1 and YKU70, and we don’t observe additive effects in dot1Δ yku70Δ/dot1Δ yku70Δ or dot1Δ ubp10Δ/dot1Δ ubp10Δ mutants (S7C–S7E Fig), we favour a model in which a common step in heterochromatin assembly is regulated by both Sir4 and histone H3 demethylation (Fig 7).

Past work has shown that recruitment of Sir4 to silencers and telomeres occurs independently of Sir2 and Sir3 [15–17,61] and this first step in the nucleation of silent chromatin may be slowed during periods of limiting Sir4 protein (Fig 7A, regulated nucleation). Dot1-dependent histone methylation directly antagonizes Sir3 binding to nucleosomes [62,63], so the absence of H3 K79 methylation in dot1Δ cells may also regulate heterochromatin nucleation by improving Sir3 recruitment to the HML silencer. In this model, coincident recruitment of Sir3 and Sir4, and their binding to one another, would be a slow step required for efficient nucleation (Fig 7A and [64]). Overexpression of Sir3 does not speed establishment [26], which is consistent with a model that Sir3 recruitment is determined by the extent of demethylation, not the concentration of Sir3. The extent of histone H3 K79 methylation at HML-E is similar (and low) in the presence or absence of SIR4 (S6 Fig), suggesting that histone H3 K79 demethylation at HML-E may be regulated independently of heterochromatin assembly, and that this function of demethylation is unlikely to be a regulated step in de novo establishment.

Alternatively, because histone H3 K79 methylation often correlates with active transcription [65–67] and competes with Sir3 and Sir4 for binding to nucleosomes [31,68,69], Dot1 may control Sir3 spreading, which could also function as a rate limiting step in de novo assembly (Fig 7B, regulated completion of assembly). In this model, low levels of Sir4 would be sufficient for the spreading of Sir proteins, but additional Sir4 would be necessary at a later step, arguing that the occupancy of Sir4 would change during transcriptional repression of this region (Fig 7B). The recruitment of the Sir4/Sir2 complex could be linked to the demethylation of histone H3 K79, as previous work has shown that Dot1 competes with Sir3 and Sir4/Sir2 for binding to the N-terminal tail of histone H4 [31,68,69].

Supporting this model, several studies have suggested histone H3 K79 demethylation functions at a late step in silent chromatin maturation [18–20,70] and one showed that de novo establishment at a modified HMRa occurred after SIR complex recruitment and spreading [20]. This work investigated de novo establishment at HMRa, which occurs more slowly than at HMLα [71,72], and establishment was triggered by the tethering of several Sir1 proteins, which recruit both Sir3 and Sir4 [73,74]. Both aspects of this experimental design, therefore, may alter the requirements for Sir4 and histone H3 K79 demethylation.

Although histone H3 K79 demethylation speeds establishment at strong silencers, in the context of mutant silencers (hmrΔE or hmrΔA), TELVII-L, or the deletion of the recruitment protein Sir1, the absence of this methylation causes defects in silencing (S5 Fig and [26,31–33,41,75]). We speculate that these defects are likely caused by the inability of the weak silencers to compete effectively with the recruitment of Sir3 non-specifically to other genomic loci [32,33,70].

Competition between heterochromatic sites regulates de novo establishment

Past work showing that telomeres act as reservoirs of Sir proteins [42,43,76–82] suggest a model in which the loss of subtelomeric silencing in yku70Δ and ubp10Δ cells liberates Sir4 from telomeres and increases its availability for de novo establishment at HMLα (Fig 7). In such a model the competition between telomeres and potential new sites of silencing would allow changes in Sir4 abundance to regulate the speed at which these new sites of heterochromatin can assemble.

rif1Δ and rif1Δ rif2Δ cells have been shown to antagonize silencing at weakened HM loci, likely due to increased recruitment of the SIR complex to telomeres, and like sir4Δ/SIR4 cells, rif1Δ rif2Δ/rif1Δ rif2Δ cells slow de novo establishment (Fig 6D). These mutants provide independent support of our hypothesis that telomere sequestration of Sir4 regulates de novo establishment. The phenotypes of rif1Δ rif2Δ/rif1Δ rif2Δ cells are milder than sir4Δ/SIR4 cells, which may explain why yku70Δ sir4Δ/yku70Δ SIR4 cells establish silencing slower than yku70Δ rif1Δ rif2Δ/yku70Δ rif1Δ rif2Δ cells. We observe similar differences in the phenotype of dot1Δ/dot1Δ cells when combined with sir4Δ/SIR4 or rif1Δ rif2Δ/rif1Δ rif2Δ, but in this situation we hypothesize that less Sir4 is needed for robust establishment at HMLα even though telomeric silencing is strengthened in rif1Δ rif2Δ/rif1Δ rif2Δ cells.

Competition between heterochromatic sites has also been described in fission yeast in which sequestration of Swi6 at telomeres regulates the efficiency of assembly of heterochromatin at other sites, and release of Swi6 from telomeres or increased Swi6 expression allows bypass of RNAi-dependent assembly of pericentric heterochromatin [83]. This work suggested that a function of telomeric heterochromatin is to buffer cells from changing levels of heterochromatin factors and prevent inappropriate assembly of potentially harmful heterochromatin. Our work supports this model, but also suggests that competition between telomeric heterochromatin could function to generate phenotypic diversity within a population. Sir-dependent regulation of subtelomeric genes has been shown to influence cell adhesion, cell wall remodeling and stress resistance in budding yeast, expression of cell surface antigens in Plasmodium falciparum, and colony morphologies in Candida albicans [84–89]. Some of these changes are induced by environmental factors, but variation in the expression of a heterochromatin protein, like Sir4, may also influence the competition between different subtelomeric regions to generate more subtle changes in cell identity.

How and why is Sir4 abundance regulated?

Our investigation into the role of Sir4 in de novo establishment began with the surprising observation that Sir4 abundance falls precipitously after prolonged G1 arrest (Fig 1). The re-synthesis of Sir4 after release from this arrest takes two cell cycles, which correlates with the time needed for cells to establish a new site of heterochromatin [19,21,26]. Although we are unable to monitor Sir4 protein levels during mating in individual cells, we hypothesize that the prolonged exposure to pheromone during mating also causes a drop in Sir4 protein abundance. After mating, SIR4/SIR4 zygotes would then require two cell cycles to re-synthesize Sir4 and re-establish silencing of HMLα.

The slow kinetics of Sir4 degradation may explain why this drop in abundance has not been observed previously, and suggests that the decrease in Sir4 protein levels may be induced by pheromone, and not cell cycle arrest. SIR4 transcription is unchanged during pheromone treatment [90], thus the drop in protein level is likely caused by regulated translation or degradation. Recent work has defined a pheromone-induced pathway that slows cell growth by causing inhibition of ribosome synthesis and translation [91]. The strength of this response depended on the concentration of pheromone and the extent of polarization, thus we speculate that the slow drop in Sir4 over five hours of arrest (Fig 1) may indicate that Sir4 is regulated by the same pathway.

Our finding that the abundance and availability of Sir4 can regulate de novo heterochromatin establishment suggests that changes in Sir4 abundance may be a cell cycle regulated step in de novo establishment [21,22,24,25]. However, although we have shown that modulating Sir4 abundance changes the speed of establishment in single cells (Figs 1 and 2), we have not been able to test if preventing the loss of Sir4 in pheromone arrested cells will allow for immediate re-establishment during the arrest. Identifying the mechanism that regulates Sir4 abundance will allow us to test this directly.

Chromatin fractionation revealed that both the soluble and chromatin-bound fraction of Sir4 drops during G1 arrest (S1E Fig). An explanation for this behavior is that the majority of chromatin-bound Sir4 binds to non-specific chromosomal sites and that this fraction rapidly equilibrates with soluble Sir4, such that bound and unbound bulk levels of the protein drop equally during G1 arrest. Sir4 bound at specific chromosomal sites (S1B Fig), however, may not exchange as rapidly, allowing maintenance of silencing despite low levels of Sir4.

Although the level of Sir4 protein during a pheromone arrest may be insufficient to establish new sites of silent chromatin, past work has shown that existing subtelomeric silent chromatin are more stable during a pheromone arrest [92]. The stability of existing sites would imply that two factors are at play: low levels of Sir4 prevent new sites of heterochromatin from forming, and structural or post-translational changes in Sir4 (or another silencing protein) prevent disassembly of existing sites. Recent work has shown that very low levels of Sir3, like Sir4, are also sufficient to maintain a silenced state [93]. This strategy may be useful for cells arrested in G1, where maintenance of cell identity is critical as cells make developmental choices including the decision to mate, to initiate the meiotic program, to enter the cell cycle, or to enter quiescence. In addition, low levels of Sir4 have also been shown to improve silencing within the rDNA [82], providing a mechanism for cells to maintain rDNA integrity during persistent G1 arrest. Similar developmental decisions are made in vertebrate cells in G1, and similar mechanisms may be used to protect cell identity.

Materials and Methods

Ethics statement

This study was performed in strict accordance with standards for animal care and use outlined in the Canadian Council on Animal Care Standards. The University of Ottawa is a registered research facility under the Province of Ontario's Animals for Research Act. The protocol was approved by the University of Ottawa Animal Care Committee (Permit Number: BMI-113). All surgery was performed under sodium pentobarbital anesthesia, and every effort was made to minimize suffering.

Strain and plasmid construction

Supporting information S2 Table lists the strains used in this work. All strains, except the mating testers (ADR3081 and ADR3082; gifts from Fred Winston, Harvard Medical School) are derivatives of the W303 strain background (W303-1a; Rodney Rothstein, Columbia University, New York, NY). Strains used for the single cell mating assay (JRY8828 and JRY8829) were a gift from Erin Osborne and Jasper Rine (UC, Berkeley, CA). All deletions and replacements were confirmed by immunoblotting, phenotype or PCR. The sequences of all primers used in this study are available upon request. The bacterial strains DH5α and Rosetta (EMD-Millipore) were used for amplification of DNA.

All deletions were made using cassettes amplified from pAR747 (C. albicans URA3), pFA6a-His3MX6 (S. pombe his5+), pFA6a-kanMX6 [94], pAG29 (natMX4) [95] and pYM22 (K. lactis TRP1) [96]. pAR747 was constructed by cloning the CaURA3 gene from pKT176 [97] as a BglII/XmaI fragment into pAG29 (patMX4) [95] cut with BglII/XmaI.

The TELVII-L::URA3 and adh4::URA3 strains were made by using pTEL::URA3 and pADH4::URA3, respectively (kindly provided by Dan Gottschling, Fred Hutchison Cancer Research Center) to create ADR2828 and ADR2830, respectively.

hmrΔE::TRP1 [35] strains were constructed by crossing derivatives of CCFY100 (kindly provided by Kurt W. Runge, The Lerner Research Institute, Cleveland, OH) [98] to create ADR4062 which was subsequently used to create other hmrΔE::TRP1 strains.

hmrΔA::ADE2 [35,99] strains (kindly provided by David Shore (University of Geneva, Switzerland) via Marc Gartenberg (Rutgers, NJ)) were constructed by deleting DOT1, UBP10 and YKU70 in GCY317.

The SIR4-eGFP strain was created using pKT127 [97]. his3-11,15::pGAL-SIR4-HIS3 strains were created by integrating pAR655 cut with BsiWI into the appropriate strains. pAR655 was constructed by amplifying the entire SIR4 ORF by PCR and cloning it as a ClaI/EcoR1 fragment into pAR121. pAR121 is pRS303 [100] with the GAL1-10 promoter cloned between the KpnI/XhoI sites.

leu2-3,112::pMRP7-GAL4-ER-VP16-LEU2 strains were created by integrating pAR941 cut with XcmI. pAR941 was created by cloning the pGEV cassette as a FspI fragment from pGEV-HIS3 [38] into pRS305 [100].

SIR4-CEN plasmids, pAR646 and pAR722 were created by cloning the XhoI/EcoR1 fragment that contains SIR4 from pAR465 into pRS313 (HIS3) and pRS316 (URA3) [100] respectively. pAR465 is a modified version of LSD343 (pRS314-SIR4; kindly provided by David Shore) which includes 216 nt downstream of the STOP codon followed by a XhoI site and a silent MluI site has been introduced at nt2850 (changing AAGAGT to ACGCGT). pAR450 contains the same SIR4 fragment as pAR465 (without the MluI site) cloned into pRS313 [100]. pRS313 and pRS316 [100] were used as empty CEN plasmids in pedigree experiments. The SIR4-2μ plasmid was created by cloning the XhoI/EcoR1 fragment that contains SIR4 from pAR646 into pRS423 (HIS3) [100]. pRS423 was used as the empty 2μ plasmid in pedigree experiments.

Pedigree assay

The single cell establishment pedigree assay was performed as described in Osborne et al. [26] with minor variations. Cells were grown overnight on plates of either YEP + 2% Dextrose, YEP + 2% Raffinose or synthetic selective media at 30°C, with the exception of ku70Δ dot1Δ (ADR5920 and ADR5921) and ku70Δ dot4Δ (ADR5944 and ADR5945) cells which were grown at 25°C overnight due to a slight temperature sensitivity. A small number of cells of each experimental strain were resuspended in YEP and each spotted onto a YEP +2% dextrose plate along with a thick streak of MATα (ADR22) cells. Individual cells from the two experimental strains were micro-manipulated (Nikon Eclipse 50i, 20X S Plan Fluor, NA0.45, with TDM50 micromanipulator) next to one another and allowed to mate over one to two hours. Zygotes were micro-manipulated adjacent to the streak of MATα cells and allowed to grow at 30°C. As the zygote (and subsequent daughters) divided, daughters were separated and moved in order to observe and score the behavior of the pedigree. Cells were monitored every one hour by microscopy and tracked for three divisions or until all cells in the pedigree had arrested and shmooed. Similar to Osborne et al. [26], we did not observe plate-specific or day-specific effects on the pedigree patterns, and we therefore pooled data from several plates to compile the distributions for each genotype tested.

Statistical differences between pedigree distributions were determined by likelihood ratio test as described [26]. Each distribution was compared pair-wise, and the complete dataset can be found in Supporting Information S1 Table.

Physiology and microscopy

Cell cycle arrests were performed with 10μg/mL nocodazole (Sigma-Aldrich), 1μg/mL α-factor (Biosynthesis) or 0.2M hydroxyurea (HU; Sigma) at 25°C.

To image Sir4 foci, SIR4-GFP and wild type (ADR4006) control cells were grown overnight in YEP + 2% dextrose to log phase, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 minutes, washed, sonicated and resuspended in 100mM KPO4 containing 1.2M sorbitol. Samples were imaged using a Nikon TI microscope (Nikon) with a Nikon Plan Apo 60X 1.4 NA objective and FITC filter set (Chroma) at room temperature with a Photometrics CoolsnapHQ2 camera (Photometrics). 13 fluorescent images using no ND filters and an exposure time of 2s were obtained separated by 0.5μm along the Z-axis. A single brightfield image was obtained at the central plane with an exposure time of 200ms. Example images were prepared using ImageJ software. Imaging was done in mixed populations of nocodazole (mitotic) and α-factor (G1) treated cells; the two cell types were determined by cell morphology. The same linear look-up-table was used for each example image. Fluorescence quantification was done using NIS-Elements software. For each cell three fluorescent foci were analyzed. A total of eight cells of each genotype were obtained in two separate experiments. Mean fluorescence in a 0.25um2 circular ROI was obtained for each focus. For each focus, mean fluorescence from a similar sized background ROI obtained from the same cell and focal plane was subtracted. Non-focus fluorescence measurements were obtained as described above but all images were obtained at the same Z-plane. Three measurements were obtained in each of eight cells from two separate experiments.

Silencing assays

For serial dilution assays, cells were grown for two days in YEP + 2% dextrose or synthetic selective media + 2% dextrose at 30°C, and cultures were spotted on the indicated media in 10-fold serial dilutions using a multi-prong applicator (Dan-Kar), and grown at 30°C for two to three days.

Quantitative mating was performed as described previously [61]. Tested strains and tester strains were placed on YEP + 2% glucose plates and grown overnight at 30°C. On the following morning, the cells were scraped from the plates, and heavily inoculated into YEP + 2% dextrose liquid medium and grown for two to four hours at 25°C to an OD600 of one to two for the tested strains and to an OD600 of four to six for the tester strains. Quantities of 106, 105, 104, 103, and 102 cells of the tested strain (in 100μl) were mixed with 107 to 5 X 107 cells of the tester strain (in 300μl). The mixture was plated directly on synthetic minimal + 2% dextrose plates and grown at 25°C for 3 days, and then colony counting was performed to determine the mating efficiency. A quantity of 102 cells of the tested strain was also plated on synthetic complete + 2% dextrose plates to accurately determine the number of viable cells that were mated in the experiment. Within each experiment, matings were done in duplicate, and at least three independent mating experiments were performed. Mating efficiencies are typically between 50 and 100% for wild type cells (ADR21 and ADR22). The matings in Figs 2D, 5B and 5C and 6E were performed by different individuals (S.P., C.D. and A.D.R.) and accounts for the differences in efficiencies between identical (JRY8828 X JRY8829) and similar (ADR21 and ADR22) strains.

hmrΔA::ADE2 cells were grown at 30°C overnight in liquid YEP + 2% dextrose media, 200–500 cells plated on YEP + 2% dextrose plates and grown for 3 days at 30°C. The plates were then left at 4 degrees to allow the red color to develop. Cells were scored for their ability to completely silence/express the ADE2 locus (red or white) or switch between silenced and unsilenced states (sectored colonies).

Western blots

These methods have been described previously [61,101]. Yeast extracts for Western blotting were made by bead beating (multitube bead beater; Biospec) frozen cell pellets in 1X sample buffer (2% SDS, 80mM Tris-HCl pH6.8, 10% glycerol, 10mM EDTA, bromophenol blue, 5% 2-mercaptoethanol). Samples were normalized by cell concentration before harvesting.

Standard methods were used for polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and protein transfer to nitrocellulose (Pall). Typically, samples were run on 12.5% polyacrylamide gels (120 : 1 acrylamide:bis, respectively, with no added SDS). Blots were stained with Ponceau S to confirm transfer and equal loading of samples, and then were blocked for 30 min in blocking buffer (4% nonfat dried milk (Carnation) in TBST (20mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween 20). All antibodies were incubated overnight at 4°C or for 2 h at 25°C. After washing with TBST, the blots were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit antibodies (Bio-Rad) at a 1 : 5,000 dilution in blocking buffer for 30 min at 25°C, washed again, incubated with Western Lightning reagents (Perkin-Elmer) and then exposed to X-Omat film (Kodak) or imaged on a GE Image Quant LAS4010 (GE) imaging system. Densitometry of bands was performed using ImageQuant TL (GE) software.

Affinity-purified rabbit polyclonal anti-Sir2 [102] and anti-Sir4 antibodies were used at a dilution of 1 : 2,500, and anti-Sir3 and anti-histone H4 (Millipore; 04–858) were used at a dilution of 1 : 1000, in antibody storage buffer (autoclaved 4% nonfat dried milk, TBST, 5% glycerol, 0.02% NaN3). Anti-Cdk1 antibody [101] was used at a dilution of 1 : 1000 in BSA storage buffer (sterile 2% BSA, TBST, 0.02% NaN3).

Anti-Sir3 and anti-Sir4 antibodies were generated as follows. His6-Sir3 (aa522-978) and GST-Sir4 (aa1165-1358) was expressed in bacteria from pAR1007 and pAR411, respectively (kindly provided by Danesh Moazed, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA). 1mg of each fusion protein was injected into rabbits every 4 weeks for 8 to 16 weeks (uOttawa animal facility). Rabbit serum was harvested, clarified by centrifugation and loaded on Affigel-10 (Bio-rad) columns coupled to purified His6-Sir3 (aa522-978) and malE-Sir4 (aa1165-1358), respectively. malE-Sir4 (aa1165-1358) was expressed from pAR653 in which Sir4 (aa1165-1358) was cloned as BamH1/Sal1 fragments into pMAL-c2 (NEB). Antibody was eluted from Affigel columns with either 100mM triethylamine pH 11.5 or 100mM glycine pH 2.3. The triethylamine and glycine elutions were neutralized, dialyzed in PBS + 50% glycerol and stored at -80°C.

Chromatin fractionation

Chromatin fractionation was performed as described previously [103]. 0.5 X 109 cells at ~2 X 107 cells/ml were harvested and sodium azide was added to 0.1%. Cells were washed once in pre-spheroplasting buffer (100mM PIPES (pH 9.4), 10mM DTT) and then incubated for ten minutes at room temperature in 5 ml of the same buffer. Cells were collected by centrifugation and resuspended in 1 ml of spheroplasting buffer (50mM KH2PO4/ K2HPO4 (pH 7.5), 0.6M Sorbitol, 10mM DTT) containing 50μl of 2mg/ml Lyticase (Sigma) and incubated at room temperature with end-over-end mixing for 10–20 minutes. Spheroplasting was considered complete when the OD600 of a 1 : 100 dilution of the cell suspension (in water) dropped to <10% of the value before digestion. Spheroplasts were washed with 1 ml of ice-chilled wash buffer (100mM KCl, 50mM HEPES-KOH (pH 7.5), 2.5mM MgCl2, and 0.4M Sorbitol), pelleted at 4000 rpm for 1 min in a microcentrifuge at 4°C, and resuspended in 500μl of extraction buffer (100mM KCl, 50mM HEPES-KOH (pH 7.5), 2.5mM MgCl2, 50mM NaF, 1mM NaVO3, and added fresh: 1mM PMSF, 1mM benzamidine HCl, and 10μg/ml of leupeptin, pepstatin, bestatin and chymostatin). Spheroplasts were lysed by adding Triton X-100 to 0.25% and incubating on ice for 5 min with gentle mixing. A portion of the total lysate (T) was removed and mixed with 2X sample buffer, and the remaining lysate was spun at 12,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant (S) was removed and a portion mixed with 2X sample buffer. The crude chromatin pellet (C) was washed with extraction buffer containing 0.25% Triton X-100, and spun again at 10,000 rpm for 5 min at 4°C. The pellet was resuspended in the wash buffer and then mixed with 2X sample buffer. Fractions were heated at 65°C for ten minutes and equal cell equivalent volumes were run on polyacrylamide gels (12.5% and 20%) and processed for western blotting with the indicated antibodies.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

Chromatin immunoprecipitation was performed as described previously {Rudner:2005fd}. Sir4 was precipitated with 1μl of affinity purified rabbit polyclonal anti-Sir4 antibody, histone H3 was precipitated with 1μl of rabbit anti-histone H3 antibody (Millipore; 04–928) and histone H3 methylated on K79 was precipitated with 1μl of rabbit anti histone H3-pan-methyl K79 antibody (AbCam; ab28940). PCR was performed with 0.1mCi [α-32P] dCTP (3,000 Ci/mmol; Perkin Elmer), reactions were resolved on 6% acrylamide (30 : 1 acrylamide:bis)-Tris-borate-EDTA gels, and quantified by phosphorimaging on a Typhoon Trio phosphorimager and ImageQuant software (GE Healthcare).

Relative fold enrichment values for each strain were calculated as follows: [silent locus (immunoprecipitate)/ACT1 (immunoprecipitate)]/[silent locus (input)/ACT1 (input)]. The average and standard error for three independent experiments were determined. For clarity, these values were scaled so that the average values of sir4Δ in the Sir4 ChIP was set to one; the average values were scaled so that the dot1Δ values in the histone H3 ChIP was set to one.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. Kueng S, Oppikofer M, Gasser SM. SIR Proteins and the Assembly of Silent Chromatin in Budding Yeast. Annu Rev Genet. 2013. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-021313-173730

2. Rusche LN, Kirchmaier AL, Rine J. The establishment, inheritance, and function of silenced chromatin in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Annu Rev Biochem. 2003;72 : 481–516. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161547 12676793

3. Imai S, Armstrong CM, Kaeberlein M, Guarente L. Transcriptional silencing and longevity protein Sir2 is an NAD-dependent histone deacetylase. Nature. 2000;403 : 795–800. doi: 10.1038/35001622 10693811

4. Tanny JC, Dowd GJ, Huang J, Hilz H, Moazed D. An enzymatic activity in the yeast Sir2 protein that is essential for gene silencing. Cell. 1999;99 : 735–745. 10619427

5. Tanner KG, Landry J, Sternglanz R, Denu JM. Silent information regulator 2 family of NAD - dependent histone/protein deacetylases generates a unique product, 1-O-acetyl-ADP-ribose. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97 : 14178–14182. doi: 10.1073/pnas.250422697 11106374

6. Hecht A, Laroche T, Strahl-Bolsinger S, Gasser SM, Grunstein M. Histone H3 and H4 N-termini interact with SIR3 and SIR4 proteins: a molecular model for the formation of heterochromatin in yeast. Cell. 1995;80 : 583–592. 7867066

7. Johnson A, Li G, Sikorski TW, Buratowski S, Woodcock CL, Moazed D. Reconstitution of heterochromatin-dependent transcriptional gene silencing. Mol Cell. 2009;35 : 769–781. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.07.030 19782027

8. Martino F, Kueng S, Robinson P, Tsai-Pflugfelder M, van Leeuwen F, Ziegler M, et al. Reconstitution of yeast silent chromatin: multiple contact sites and O-AADPR binding load SIR complexes onto nucleosomes in vitro. Mol Cell. 2009;33 : 323–334. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.01.009 19217406

9. Aparicio OM, Billington BL, Gottschling DE. Modifiers of position effect are shared between telomeric and silent mating-type loci in S. cerevisiae. Cell. 1991;66 : 1279–1287. 1913809

10. Klar AJ, Fogel S, Macleod K. MAR1-a Regulator of the HMa and HMalpha Loci in SACCHAROMYCES CEREVISIAE. Genetics. 1979;93 : 37–50. 17248968

11. Ivy JM, Klar AJ, Hicks JB. Cloning and characterization of four SIR genes of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1986;6 : 688–702. 3023863

12. Rine J, Herskowitz I. Four genes responsible for a position effect on expression from HML and HMR in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1987;116 : 9–22. 3297920

13. Haber JE, George JP. A mutation that permits the expression of normally silent copies of mating-type information in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1979;93 : 13–35. 16118901

14. Hopper AK, Hall BD. Mutation of a heterothallic strain to homothallism. Genetics. 1975;80 : 77–85. 1093938

15. Luo K, Vega-Palas MA, Grunstein M. Rap1-Sir4 binding independent of other Sir, yKu, or histone interactions initiates the assembly of telomeric heterochromatin in yeast. Genes Dev. 2002;16 : 1528–1539. doi: 10.1101/gad.988802 12080091

16. Rusche LN, Kirchmaier AL, Rine J. Ordered nucleation and spreading of silenced chromatin in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13 : 2207–2222. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-03-0175 12134062

17. Hoppe GJ, Tanny JC, Rudner AD, Gerber SA, Danaie S, Gygi SP, et al. Steps in assembly of silent chromatin in yeast: Sir3-independent binding of a Sir2/Sir4 complex to silencers and role for Sir2-dependent deacetylation. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22 : 4167–4180. 12024030

18. Kitada T, Kuryan BG, Tran NNH, Song C, Xue Y, Carey M, et al. Mechanism for epigenetic variegation of gene expression at yeast telomeric heterochromatin. Genes Dev. 2012;26 : 2443–2455. doi: 10.1101/gad.201095.112 23124068

19. Katan-Khaykovich Y, Struhl K. Heterochromatin formation involves changes in histone modifications over multiple cell generations. EMBO J. 2005;24 : 2138–2149. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600692 15920479

20. Kirchmaier AL, Rine J. Cell cycle requirements in assembling silent chromatin in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26 : 852–862. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.3.852-862.2006 16428441

21. Miller AM, Nasmyth KA. Role of DNA replication in the repression of silent mating type loci in yeast. Nature. 1984;312 : 247–251. 6390211

22. Lau A, Blitzblau H, Bell SP. Cell-cycle control of the establishment of mating-type silencing in S. cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 2002;16 : 2935–2945. doi: 10.1101/gad.764102 12435634

23. Fox CA, Ehrenhofer-Murray AE, Loo S, Rine J. The origin recognition complex, SIR1, and the S phase requirement for silencing. Science. 1997;276 : 1547–1551. 9171055

24. Li YC, Cheng TH, Gartenberg MR. Establishment of transcriptional silencing in the absence of DNA replication. Science. 2001;291 : 650–653. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5504.650 11158677

25. Kirchmaier AL, Rine J. DNA replication-independent silencing in S. cerevisiae. Science. 2001;291 : 646–650. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5504.646 11158676

26. Osborne EA, Dudoit S, Rine J. The establishment of gene silencing at single-cell resolution. Nat Genet. 2009;41 : 800–806. doi: 10.1038/ng.402 19543267

27. Venkatasubrahmanyam S, Hwang WW, Meneghini MD, Tong AHY, Madhani HD. Genome-wide, as opposed to local, antisilencing is mediated redundantly by the euchromatic factors Set1 and H2A.Z. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104 : 16609–16614. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700914104 17925448

28. Martins-Taylor K, Sharma U, Rozario T, Holmes SG. H2A.Z (Htz1) controls the cell-cycle-dependent establishment of transcriptional silencing at Saccharomyces cerevisiae telomeres. Genetics. 2011;187 : 89–104. doi: 10.1534/genetics.110.123844 20980239

29. Lacoste N, Utley RT, Hunter JM, Poirier GG, Côté J. Disruptor of telomeric silencing-1 is a chromatin-specific histone H3 methyltransferase. 2002;277 : 30421–30424. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200366200 12097318

30. Briggs SD, Bryk M, Strahl BD, Cheung WL, Davie JK, Dent SY, et al. Histone H3 lysine 4 methylation is mediated by Set1 and required for cell growth and rDNA silencing in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 2001;15 : 3286–3295. doi: 10.1101/gad.940201 11751634

31. Fingerman IM, Li H-C, Briggs SD. A charge-based interaction between histone H4 and Dot1 is required for H3K79 methylation and telomere silencing: identification of a new trans-histone pathway. Genes Dev. 2007;21 : 2018–2029. doi: 10.1101/gad.1560607 17675446

32. van Leeuwen F, Gafken PR, Gottschling DE. Dot1p modulates silencing in yeast by methylation of the nucleosome core. Cell. 2002;109 : 745–756. 12086673

33. Ng HH, Feng Q, Wang H, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Zhang Y, et al. Lysine methylation within the globular domain of histone H3 by Dot1 is important for telomeric silencing and Sir protein association. Genes Dev. 2002;16 : 1518–1527. doi: 10.1101/gad.1001502 12080090

34. Osborne EA, Hiraoka Y, Rine J. Symmetry, asymmetry, and kinetics of silencing establishment in Saccharomyces cerevisiae revealed by single-cell optical assays. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108 : 1209–1216. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018742108 21262833

35. Sussel L, Vannier D, Shore D. Epigenetic switching of transcriptional states: cis - and trans-acting factors affecting establishment of silencing at the HMR locus in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13 : 3919–3928. 8321199

36. Gotta M, Laroche T, Formenton A, Maillet L, Scherthan H, Gasser SM. The clustering of telomeres and colocalization with Rap1, Sir3, and Sir4 proteins in wild-type Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Biol. 1996;134 : 1349–1363. 8830766

37. Laroche T, Martin SG, Tsai-Pflugfelder M, Gasser SM. The dynamics of yeast telomeres and silencing proteins through the cell cycle. J Struct Biol. 2000;129 : 159–174. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.2000.4240 10806066

38. Gao CY, Pinkham JL. Tightly regulated, beta-estradiol dose-dependent expression system for yeast. BioTechniques. 2000;29 : 1226–1231. 11126125

39. Marshall M, Mahoney D, Rose A, Hicks JB, Broach JR. Functional domains of SIR4, a gene required for position effect regulation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7 : 4441–4452. 3325825

40. Cockell M, Palladino F, Laroche T, Kyrion G, Liu C, Lustig AJ, et al. The carboxy termini of Sir4 and Rap1 affect Sir3 localization: evidence for a multicomponent complex required for yeast telomeric silencing. J Cell Biol. 1995;129 : 909–924. 7744964

41. Singer MS, Kahana A, Wolf AJ, Meisinger LL, Peterson SE, Goggin C, et al. Identification of high-copy disruptors of telomeric silencing in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1998;150 : 613–632. 9755194

42. Marcand S, Buck SW, Moretti P, Gilson E, Shore D. Silencing of genes at nontelomeric sites in yeast is controlled by sequestration of silencing factors at telomeres by Rap 1 protein. Genes Dev. 1996;10 : 1297–1309. 8647429

43. Buck SW, Shore D. Action of a RAP1 carboxy-terminal silencing domain reveals an underlying competition between HMR and telomeres in yeast. Genes Dev. 1995;9 : 370–384. 7867933

44. Smeal T, Claus J, Kennedy B, Cole F, Guarente L. Loss of transcriptional silencing causes sterility in old mother cells of S. cerevisiae. Cell. 1996;84 : 633–642. 8598049

45. Kennedy BK, Austriaco NR, Zhang J, Guarente L. Mutation in the silencing gene SIR4 can delay aging in S. cerevisiae. Cell. 1995;80 : 485–496. 7859289

46. Gardner RG, Nelson ZW, Gottschling DE. Ubp10/Dot4p regulates the persistence of ubiquitinated histone H2B: distinct roles in telomeric silencing and general chromatin. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25 : 6123–6139. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.14.6123-6139.2005 15988024

47. Emre NCT, Ingvarsdottir K, Wyce A, Wood A, Krogan NJ, Henry KW, et al. Maintenance of low histone ubiquitylation by Ubp10 correlates with telomere-proximal Sir2 association and gene silencing. Mol Cell. 2005;17 : 585–594. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.01.007 15721261

48. Orlandi I, Bettiga M, Alberghina L, Vai M. Transcriptional profiling of ubp10 null mutant reveals altered subtelomeric gene expression and insurgence of oxidative stress response. 2004;279 : 6414–6425. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306464200

49. Boulton SJ, Jackson SP. Components of the Ku-dependent non-homologous end-joining pathway are involved in telomeric length maintenance and telomeric silencing. EMBO J. 1998;17 : 1819–1828. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.6.1819 9501103

50. Lopez CR, Ribes-Zamora A, Indiviglio SM, Williams CL, Haricharan S, Bertuch AA. Ku must load directly onto the chromosome end in order to mediate its telomeric functions. Cohen-Fix O, editor. PLoS Genet. Public Library of Science; 2011;7: e1002233. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002233

51. Gartenberg MR, Neumann FR, Laroche T, Blaszczyk M, Gasser SM. Sir-mediated repression can occur independently of chromosomal and subnuclear contexts. Cell. 2004;119 : 955–967. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.008 15620354

52. Patterson EE, Fox CA. The Ku complex in silencing the cryptic mating-type loci of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2008;180 : 771–783. doi: 10.1534/genetics.108.091710 18716325

53. Vandre CL, Kamakaka RT, Rivier DH. The DNA end-binding protein Ku regulates silencing at the internal HML and HMR loci in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2008;180 : 1407–1418. doi: 10.1534/genetics.108.094490 18791224

54. Mishra K, Shore D. Yeast Ku protein plays a direct role in telomeric silencing and counteracts inhibition by rif proteins. Curr Biol. 1999;9 : 1123–1126. 10531008

55. Wotton D, Shore D. A novel Rap1p-interacting factor, Rif2p, cooperates with Rif1p to regulate telomere length in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 1997;11 : 748–760. 9087429

56. Hardy CF, Sussel L, Shore D. A RAP1-interacting protein involved in transcriptional silencing and telomere length regulation. Genes Dev. 1992;6 : 801–814. 1577274

57. Moretti P, Freeman K, Coodly L, Shore D. Evidence that a complex of SIR proteins interacts with the silencer and telomere-binding protein RAP1. Genes Dev. 1994;8 : 2257–2269. 7958893

58. Moretti P, Shore D. Multiple interactions in Sir protein recruitment by Rap1p at silencers and telomeres in yeast. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21 : 8082–8094. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.23.8082-8094.2001 11689698

59. Liu C, Lustig AJ. Genetic analysis of Rap1p/Sir3p interactions in telomeric and HML silencing in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1996;143 : 81–93. 8722764

60. Liu C, Mao X, Lustig AJ. Mutational analysis defines a C-terminal tail domain of RAP1 essential for Telomeric silencing in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1994;138 : 1025–1040. 7896088

61. Rudner AD, Hall BE, Ellenberger T, Moazed D. A nonhistone protein-protein interaction required for assembly of the SIR complex and silent chromatin. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25 : 4514–4528. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.11.4514-4528.2005 15899856

62. Onishi M, Liou G-G, Buchberger JR, Walz T, Moazed D. Role of the conserved Sir3-BAH domain in nucleosome binding and silent chromatin assembly. Mol Cell. 2007;28 : 1015–1028. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.12.004 18158899

63. Armache K-J, Garlick JD, Canzio D, Narlikar GJ, Kingston RE. Structural basis of silencing: Sir3 BAH domain in complex with a nucleosome at 3.0 Å resolution. Science. 2011;334 : 977–982. doi: 10.1126/science.1210915 22096199

64. Moazed D. Mechanisms for the inheritance of chromatin States. Cell. 2011;146 : 510–518. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.013 21854979

65. Miao F, Natarajan R. Mapping global histone methylation patterns in the coding regions of human genes. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25 : 4650–4661. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.11.4650-4661.2005 15899867

66. Schübeler D, MacAlpine DM, Scalzo D, Wirbelauer C, Kooperberg C, van Leeuwen F, et al. The histone modification pattern of active genes revealed through genome-wide chromatin analysis of a higher eukaryote. Genes Dev. 2004;18 : 1263–1271. doi: 10.1101/gad.1198204 15175259

67. Schulze JM, Jackson J, Nakanishi S, Gardner JM, Hentrich T, Haug J, et al. Linking cell cycle to histone modifications: SBF and H2B monoubiquitination machinery and cell-cycle regulation of H3K79 dimethylation. Mol Cell. 2009;35 : 626–641. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.07.017 19682934

68. Altaf M, Utley RT, Lacoste N, Tan S, Briggs SD, Côté J. Interplay of chromatin modifiers on a short basic patch of histone H4 tail defines the boundary of telomeric heterochromatin. Mol Cell. 2007;28 : 1002–1014. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.12.002 18158898

69. Oppikofer M, Kueng S, Martino F, Soeroes S, Hancock SM, Chin JW, et al. A dual role of H4K16 acetylation in the establishment of yeast silent chromatin. EMBO J. 2011;30 : 2610–2621. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.170 21666601

70. Yang B, Britton J, Kirchmaier AL. Insights into the impact of histone acetylation and methylation on Sir protein recruitment, spreading, and silencing in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Mol Biol. 2008;381 : 826–844. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.06.059 18619469

71. Lazarus AG, Holmes SG. A cis-acting tRNA gene imposes the cell cycle progression requirement for establishing silencing at the HMR locus in yeast. Genetics. 2011;187 : 425–439. doi: 10.1534/genetics.110.124099 21135074

72. Ren J, Wang C-L, Sternglanz R. Promoter Strength Influences the S Phase Requirement for Establishment of Silencing at the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Silent Mating Type Loci. Genetics. 2010;186 : 551–U172. doi: 10.1534/genetics.110.120592 20679515

73. Triolo T, Sternglanz R. Role of interactions between the origin recognition complex and SIR1 in transcriptional silencing. Nature. 1996;381 : 251–253. doi: 10.1038/381251a0 8622770

74. Connelly JJ, Yuan P, Hsu H-C, Li Z, Xu R-M, Sternglanz R. Structure and function of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Sir3 BAH domain. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26 : 3256–3265. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.8.3256-3265.2006 16581798

75. van Welsem T, Frederiks F, Verzijlbergen KF, Faber AW, Nelson ZW, Egan DA, et al. Synthetic lethal screens identify gene silencing processes in yeast and implicate the acetylated amino terminus of Sir3 in recognition of the nucleosome core. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28 : 3861–3872. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02050-07 18391024

76. Kennedy BK, Gotta M, Sinclair DA, Mills K, McNabb DS, Murthy M, et al. Redistribution of silencing proteins from telomeres to the nucleolus is associated with extension of life span in S. cerevisiae. Cell. 1997;89 : 381–391. 9150138

77. Mills KD, Sinclair DA, Guarente L. MEC1-dependent redistribution of the Sir3 silencing protein from telomeres to DNA double-strand breaks. Cell. 1999;97 : 609–620. 10367890

78. Martin SG, Laroche T, Suka N, Grunstein M, Gasser SM. Relocalization of telomeric Ku and SIR proteins in response to DNA strand breaks in yeast. Cell. 1999;97 : 621–633. 10367891

79. McAinsh AD, Scott-Drew S, Murray JA, Jackson SP. DNA damage triggers disruption of telomeric silencing and Mec1p-dependent relocation of Sir3p. Curr Biol. 1999;9 : 963–966. 10508591

80. Maillet L, Boscheron C, Gotta M, Marcand S, Gilson E, Gasser SM. Evidence for silencing compartments within the yeast nucleus: a role for telomere proximity and Sir protein concentration in silencer-mediated repression. Genes Dev. 1996;10 : 1796–1811. 8698239

81. Taddei A, Van Houwe G, Nagai S, Erb I, van Nimwegen E, Gasser SM. The functional importance of telomere clustering: global changes in gene expression result from SIR factor dispersion. Genome Research. 2009;19 : 611–625. doi: 10.1101/gr.083881.108 19179643

82. Smith JS, Brachmann CB, Pillus L, Boeke JD. Distribution of a limited Sir2 protein pool regulates the strength of yeast rDNA silencing and is modulated by Sir4p. Genetics. 1998;149 : 1205–1219. 9649515

83. Tadeo X, Wang J, Kallgren SP, Liu J, Reddy BD, Qiao F, et al. Elimination of shelterin components bypasses RNAi for pericentric heterochromatin assembly. Genes Dev. 2013;27 : 2489–2499. doi: 10.1101/gad.226118.113 24240238

84. Ai W, Bertram PG, Tsang CK, Chan TF, Zheng XFS. Regulation of subtelomeric silencing during stress response. Mol Cell. 2002;10 : 1295–1305. 12504006