-

Články

- Časopisy

- Kurzy

- Témy

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Linking Aβ42-Induced Hyperexcitability to Neurodegeneration, Learning and Motor Deficits, and a Shorter Lifespan in an Alzheimer’s Model

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most prevalent form of dementia in the elderly population. While it is established that β-amyloid (Aβ) peptide accumulation is a primary even leading to AD, there is little known about how Aβ induces progressive neurodegeneration and decline in cognitive and motor function. Recently, over-production of Aβ has been shown to result in increased neuronal excitability, and Ca2+ “overload”, in hippocampal and cortical neurons. Increased excitability is also consistent with behavioral studies which have shown enhanced seizure activity in mouse models with increased Aβ expression, and increased risk of epilepsy in AD patients. We use a transgenic Drosophila model that expresses the secreted human Aβ42; this Aβ42-Drosophila line exhibits many of the hallmarks of AD. We show that the Aβ42-Drosophila line also displays increased neuronal excitability. We determine that the increase in excitability is due to the degradation of a specific K+ channel, Kv4. We then show that genetic restoration of Kv4 attenuates age-dependent learning and locomotor deficits, slows the onset of neurodegeneration, and partially rescues premature death seen in Aβ42-expressing animals. We conclude that Aβ42-induced hyperactivity plays a critical role in the age-dependent cognitive and motor decline of this Aβ42-Drosophila model, and possibly in AD.

Published in the journal: Linking Aβ42-Induced Hyperexcitability to Neurodegeneration, Learning and Motor Deficits, and a Shorter Lifespan in an Alzheimer’s Model. PLoS Genet 11(3): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1005025

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1005025Summary

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most prevalent form of dementia in the elderly population. While it is established that β-amyloid (Aβ) peptide accumulation is a primary even leading to AD, there is little known about how Aβ induces progressive neurodegeneration and decline in cognitive and motor function. Recently, over-production of Aβ has been shown to result in increased neuronal excitability, and Ca2+ “overload”, in hippocampal and cortical neurons. Increased excitability is also consistent with behavioral studies which have shown enhanced seizure activity in mouse models with increased Aβ expression, and increased risk of epilepsy in AD patients. We use a transgenic Drosophila model that expresses the secreted human Aβ42; this Aβ42-Drosophila line exhibits many of the hallmarks of AD. We show that the Aβ42-Drosophila line also displays increased neuronal excitability. We determine that the increase in excitability is due to the degradation of a specific K+ channel, Kv4. We then show that genetic restoration of Kv4 attenuates age-dependent learning and locomotor deficits, slows the onset of neurodegeneration, and partially rescues premature death seen in Aβ42-expressing animals. We conclude that Aβ42-induced hyperactivity plays a critical role in the age-dependent cognitive and motor decline of this Aβ42-Drosophila model, and possibly in AD.

Introduction

The accumulation of β-amyloid (Aβ) oligomers in the brain has strongly been implicated as a primary event in the progression of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [1–4]. While many studies have shown that Aβ induces excitatory synaptic depression [5,6], more recent reports suggest that Aβ expression also leads to neuronal hyperactivity in cortical and hippocampal neurons [7–13]. Interestingly, increased excitability and Ca2+ overload are correlated with neurons in the vicinity of Aβ plaques [9,10]. Much remains to be understood about how Aβ induces both hypo - and hyperactivity, and how these changes are temporally coordinated in the pathogenesis of AD. Some reports suggest that soluble and protofibrillar Aβ induce early hyperactivity that precedes neuronal silencing [7,8,12].

While increased excitability is consistent with enhanced seizure activity in Aβ expressing mouse models [7,11] and increased risk of epilepsy in AD patients [14], it is unknown whether, and to what extent, hyperactivity contributes to downstream effects associated with Aβ accumulation, such as impaired cognitive and motor function. In this study, our intent was to restore excitability to an Aβ-expressing model system and examine whether these age-associated effects would be ameliorated in vivo. To do this, it was critical to first identify key mechanism(s) by which excitability is increased by Aβ. A few reports have identified potential contributors to Aβ-induced hyperactivity. For example, neocortical pyramidal cells and dentate granule cells from mice overexpressing Aβ have been observed to have a more depolarized resting potential, resulting in lower action potential thresholds and increased bursts of firing [11]. An increase in spike afterdepolarization has been reported in CA1 pyramidal neurons from transgenic mice overexpressing Aβ [13]. More recently, a transgenic mouse line expressing high levels of human Aβ has been reported to have decreased levels of the voltage-gated Na+ channel, Nav1.1, in parvalbumin inhibitory interneurons [15].

Here, we use a transgenic Drosophila line that over-expresses a secreted form of the toxic human Aβ1–42 (Aβ42). These flies exhibit many of the pathogenic hallmarks associated with AD: extracellular amyloid deposits, age-dependent learning and locomotor defects, progressive neurodegeneration and premature death [16–18]. We first show that expression of human Aβ42 indeed induces neuronal hyperexcitability. Since fly brains do not share the same circuitry or complexity of mammalian systems, examining underlying circuit changes would not be meaningful. Intrinsic changes, however, are more likely to be conserved and easier to genetically “reverse”. In addition, while virtually all ion channel families are represented in flies, many families are distilled to a single gene in flies, making intrinsic changes more easily detectable. We characterized Aβ42-induced changes in excitability and show that these changes are explained by selective degradation of the highly conserved A-type K+ channel, Kv4. We then transgenically increased Kv4 to wild-type levels in Aβ42-expressing animals. We show that when excitability is restored, nearly all Aβ42-induced downstream effects including, neurodegeneration, locomotor and learning defects, and premature death, were attenuated, and in some cases, fully rescued.

Results

Characterizing Aβ42-Induced Hyperexcitability

In this study, we used a transgenic line expressing human Aβ42 fused to an N-terminal rat pre-proenkephalin signal peptide that has been shown by two different groups to direct expression, cleavage of the signal sequence, and extracellular secretion of Aβ42 [16,17], thereby mimicking human Aβ42 accumulation in the extracellular space around neurons. This sequence was placed under the control of an upstream activating sequence (UAS), UAS-Aβ42 [18]). Using the UAS-GAL4 system in Drosophila [19], UAS-Aβ42 expression was activated with the pan neuronal driver elav-GAL4 (elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/+). We first examined if these neurons from Aβ42-secreting cultures displayed increased excitability. We performed current-clamp recordings from primary neurons that were dissociated from late-gastrula stage embryos and grown for up to two weeks in culture. These neurons likely represent larval stage neurons and are among the best characterized neurons in Drosophila with respect to voltage-dependent channels and synaptic physiology [20–26].

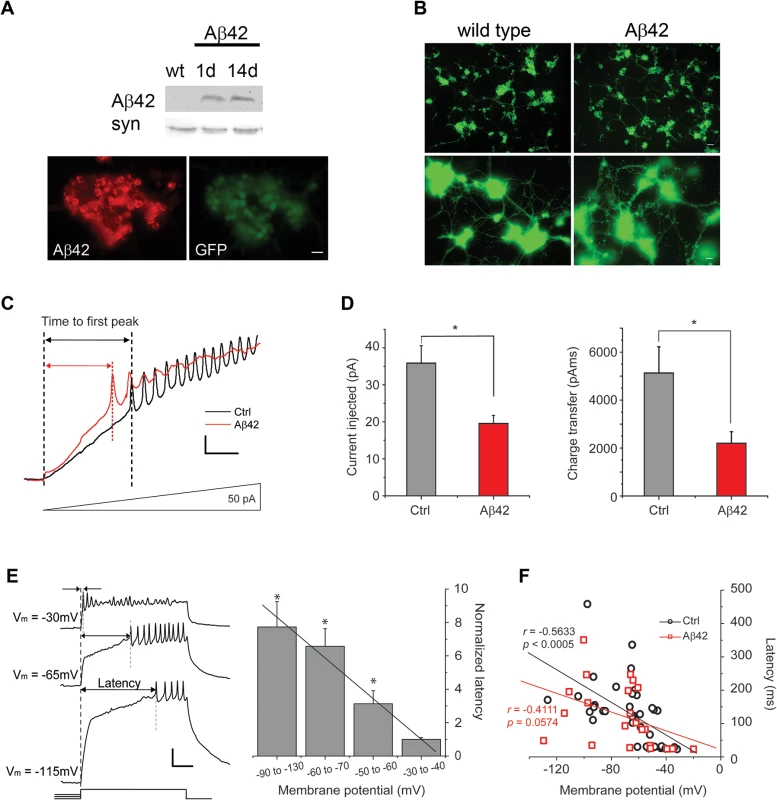

We grew cultures in 20 μL drops of media and aged them for 9 days to allow for Aβ42 expression, secretion, and accumulation; Aβ42 expression/accumulation was confirmed by immunoblot analyses (Fig. 1A) and immunostaining of cultures (Fig. 1B). No differences in neuronal growth could be seen between Aβ42-expressing cultures and control cultures (Fig. 1B). We examined action potential (AP) firing in these neurons response to an injection of current ramped from 0 to 150 pA over a 1-second period; pre-injection of current was applied to normalize membrane potentials to -50 to -60 mV (similar to the average resting potential of these cells) before ramped stimulation was applied. We found that neurons from Aβ42-expressing/secreting cultures (also referred to as Aβ42 neurons) consistently fired more readily, with less current injection, compared to neurons from a genetic background control line (Fig. 1A). AP firing in Aβ42 neurons was initiated when ramp stimulation reached only 19.5 +/ - 2.2 pA (n = 6; Fig. 1B); in contrast, control neurons fired when current injection reached 35.9 +/ - 4.7 pA (n = 13; Fig. 1B). The charge transfer required for AP firing in Aβ42 neurons was less than half of what was needed for wild-type neurons (Fig. 1B). These results suggest that neurons from Aβ42-expressing cultures indeed exhibit increased susceptibility to firing.

Fig. 1. Aβ42 induces increased neuronal excitability in cultures 9 days old.

(A) Representative immunoblots of fly heads (Top) and immunostaining of cultured neurons (Bottom) showing expression of Aβ42 in elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/+ (Aβ42) heads and elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/+;UAS-GFP neurons, respectively; absence of Aβ42 expression in wild-type (wt) is shown as a negative control. Note that immunostaining is from a large cluster of neurons identified by GFP expression. Scale bar represents 12.5 μm. (B) Shown are representative wild-type and elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/+ (Aβ42) cell cultures, both with neurons expressing GFP as a marker, at 9 days. At lower power (Top), whole cultures from a single-embryo can be seen (scale bar represents 25 μm); at higher power (Bottom), neuronal processes between clusters of neurons can be seen (scale bar represents 8 μm). No obvious differences in growth of cultured neurons between wt and Aβ42 were observed. (C) Representative current-clamp recordings from wild-type (Ctrl) and elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/+ (Aβ42) neurons, showing relative times to the first action potential (AP) firing in response to ramped current stimulation. Current injection was ramped from 0 to 150 pA over 1 sec; voltage responses to the first 336 ms (50 pA) of the ramp protocol are shown. Scale bars represent 50 ms and 10 mV. (D) Quantification of the injected current (Left) and the charge transfer (Right) required to elicit the first AP in Ctrl and Aβ42 neurons during ramp stimulation; all ramp protocols were initiated from a membrane potential of -50 to -60 mV. The average charge transfer to elicit AP firing was also significantly reduced in Aβ42 neurons (2197.4 +/- 484.46 pAms, n = 6), compared to Ctrl (5132.8 +/- 1091.32 pAms, n = 13; P < 0.05, Student’s t-test). (E) Representative traces (Left) from a wild-type neuron, showing the latency to AP firing in response to a 500 ms pulse of 20 pA current injection, following pre-injections of current that generated a membrane potential of -115, -65, or -30 mV. Latencies to AP firing was normalized to average latency at -30 to -40 mV are shown for wild-type neurons from the indicated membrane potentials (Right). Note the negative correlation between AP latency and membrane potential (* denotes a significant difference in latency compared to that at Vm = -30 to -40mV; P < 0.05, Student’s t-test). Scale bar represents 100 ms and 20 mV. (F) AP latencies, in response to 500 ms, 40 pA current pulses, from single events are plotted against membrane potential for Ctrl and Aβ42 neurons. Ctrl cells showed a significant correlation between latency and membrane potential (r = -0.5633, P < 0.0005, n = 37), while Aβ42 cells did not (r = -0.4111, P = 0.0574, n = 22); the coefficient of correlation for each genotype was calculated by the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficients (see Materials and Methods). To further characterize the hyperactivity of Aβ42 neurons, we compared AP firing in response to 500 ms current injections in neurons from background control lines and neurons from Aβ42-expressing cultures. Current pulses of 40 pA were used to examine the latency to the first AP firing; for neurons that did not fire APs, we increased current injections by 20 pA until APs were elicited. Wild-type neurons displayed a clear negative correlation between membrane potential and latency to the first AP firing (Fig. 1C-D). Interestingly, this latency to the first AP is dependent almost exclusively on Kv4 channels [26], which carry an A-type K+ current that is activated at subthreshold potentials. The number of Kv4 channels available for activation is dependent on membrane potential, such that the more depolarized the membrane potential, the smaller the number of Kv4 channels available for activation [21] and therefore, the shorter the latency to AP firing. Neurons from Aβ42-expressing cultures, in contrast to wild-type, displayed significantly reduced correlation between membrane potential and latency to AP firing (Fig. 1D). These results suggested that Kv4 channels, in particular, may be impacted by Aβ42 expression.

Kv4 Current Is Selectively Decreased by Aβ42 Expression

To test the hypothesis that Kv4 channels are affected by Aβ42 expression, we performed voltage-clamp studies to examine whether Kv4, or any other voltage-dependent K+ currents, were altered in Aβ42-expressing cultures. Fortunately, previous studies have genetically identified all of the voltage-dependent K+ currents present in these neurons: all of the A-type K+ currents (IA) present in the cell bodies of these neurons are carried by channels encoded by the single Kv4 (Shal) gene in Drosophila, while the delayed rectifier (DR) component has been shown to be encoded largely by the single Kv2 (Shab) gene, and in small part by the Kv3 (Shaw) gene [20,21]. The Kv2-Kv3 DR component was recorded using a prepulse of -45 mV to completely inactivate Kv4 channels, before stepping to a depolarized test potential; the Kv4 current was then isolated by subtracting the DR component from the whole-cell current, as performed in previous studies [20,21,25,26]. Since Aβ42 is thought to have especially detrimental effects for neurons involved in cognitive function, we focused on Kenyon cells of the mushroom bodies (MBs), which have been shown to constitute the major site of olfactory learning and memory formation in the fly brain [27–30]. To identify MB neurons, we crossed transgenic elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/+ flies to flies containing a GFP.S65T.T10 transgene, which has been shown to drive GFP expression only in MB neurons, regardless of the GAL4 driver present [30,31].

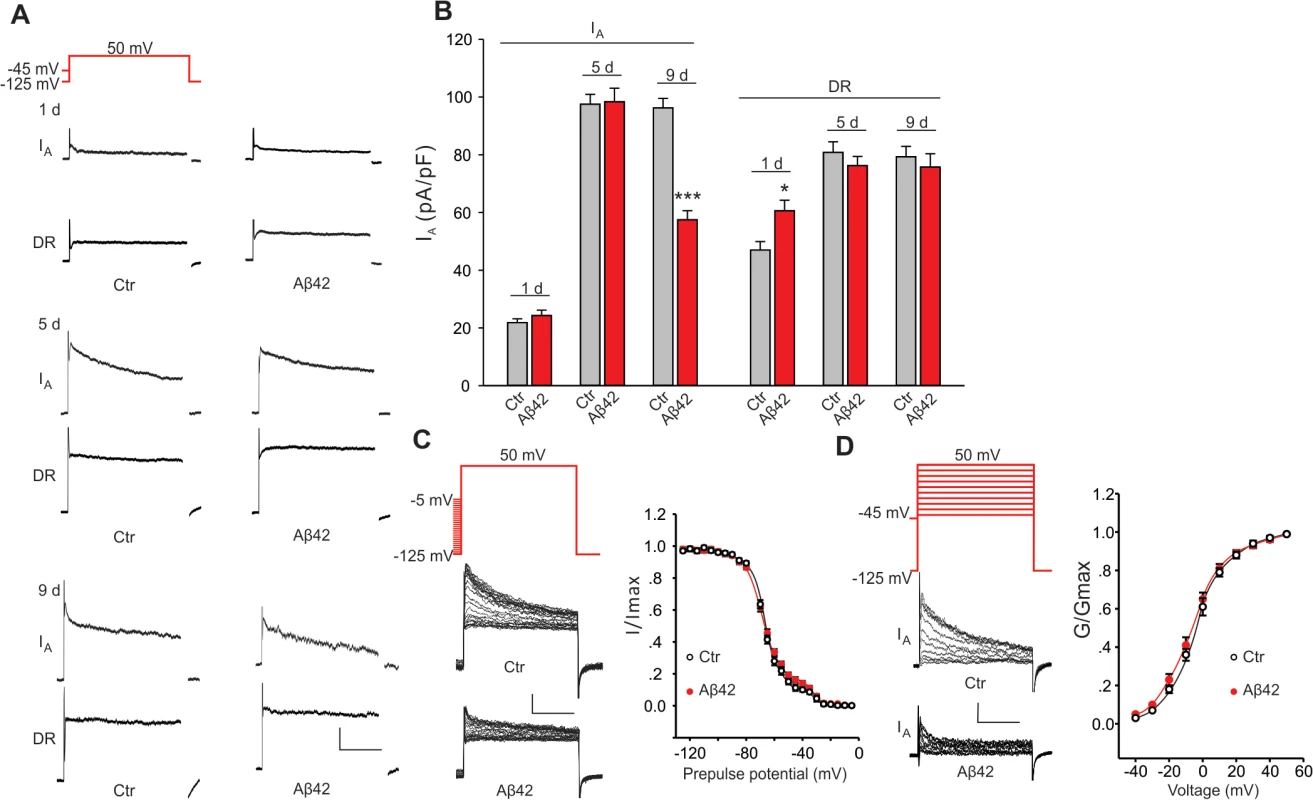

We recorded from GFP-labeled MB neurons from 20 μL drop cultures at 1, 5, and 9 days. We found that the Kv2-Kv3 DR component was increased in Aβ42 neurons at 1 day, compared to control neurons from relevant genetic background lines (UAS-Aβ42/+ or elav-GAL4); this increase, however, was not persistent after the first day (Figs. 2 and S1). More prominent was a 37% decrease in the Kv4 current density that developed in Aβ42 neurons after 9 days compared to controls (Figs. 2 and S1); no differences were seen in cell capacitance (Ctrl: 2.7 +/ - 0.2 pF, Aβ42 : 2.5 +/ - 0.1 pF), resting membrane potential (Ctrl: -55.0 +/ - 2.3 mV, Aβ42: -52.1 +/ - 2.6 mV), or input resistance (Ctrl: 2.1 +/ - 0.2 GΩ, Aβ42 : 2.2 +/ - 0.2 GΩ). The loss of Kv4 current is consistent with current-clamp recordings that show a loss of correlation between membrane potential and latency to AP firing (Fig. 1D).

Fig. 2. Aβ42-induced changes in voltage-dependent K+ currents in primary neurons.

Representative K+ current traces (A) and quantification of current amplitudes (B) from MB neuron recordings from UAS-Aβ42/+ (Ctr) and elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/+ (Aβ42) embryos cultured for 1, 5 and 9 days. The Kv2-Kv3 DR component was recorded using a prepulse of -45 mV to completely inactivate Kv4 channels, before stepping to a test potential of +50 mV; the Kv4 current was then isolated by subtracting this DR component from the total whole-cell current elicited from a prepulse of -125 mV, stepping to a test potential of +50 mV. Current density was obtained by dividing peak current amplitude by cell capacitance. Kv4 current density was significantly reduced in Aβ42 MB neurons in 9-day old cultures, while no difference in Kv2-Kv3 currents was observed. (n = 8–10 for each group, * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, Student’s t-test). Scale bars, 100 pA, 50 ms. (C-D) Steady-state inactivation and activation properties of Kv4 compared between neurons from Ctr and Aβ42 cultures. For steady-state inactivation analyses, we used a prepulse from -125 to -5 mV, in 5 mV intervals, then stepped to a test potential of +50 mV; representative current traces are shown (C, Left). For G –V analyses, we used voltage jumps from -40 to 50 mV, in 10 mV intervals, and either a prepulse of -125 mV or -45 mV for the total current or DR component, respectively; Kv4 current amplitudes were obtained by subtracting the DR component from the total current. Steady-state inactivation and activation curves were fitted with Boltzmann functions, I/Imax = 1/(1 + exp[(V – V1/2)/k]) and G/Gmax = 1/(1 + exp[(V1/2 – V)/k]), respectively. V1/2 is the half-maximal voltage, and k is the slope factor. Note that steady-state inactivation was fitted by two Boltzmann equations, and Kv4 is represented by the first Boltzmann (more negative operating range)[20,21]. There was no significant difference in half-maximal inactivation potential values (Ctr, V1/2 = -69.3 ± 2.1 mV, k = 9.1 ± 0.5; Aβ42, V1/2 = -71.2 ±3.4 mV, k = 9.7 ± 0.5). There was also no difference in the half-maximal activation potential values (Ctr, V1/2 = -5.7 ± 0.4 mV, k = 12.5 ± 0.8; Aβ42, V1/2 = -6.8 ± 0.4 mV, k = 13.6 ± 0.6). n = 10 or each group. *** P < 0.001. All neurons were from cultures 9 days old. We also examined whether the apparent loss of Kv4 current in Aβ42-expressing neurons might be due to an Aβ42-induced change in Kv4 inactivation or activation properties. We compared steady-state inactivation properties of Kv4 currents in Aβ42-expressing neurons and background controls. Whole-cell currents inactivated with more depolarized pre-pulses. As previously characterized, this inactivation was best fit with a double Boltzman equation with the component that inactivates at more hyperpolarized potentials corresponding to the Kv4 current [20,21]. No differences were observed between Aβ42-expressing and background contols (Fig. 2C). Activation properties were also not altered by Aβ42 expression (Fig. 2D). These results suggest that the Aβ42-induced decrease in Kv4 current density is not due to a change in steady-state inactivation or activation properties of the channel.

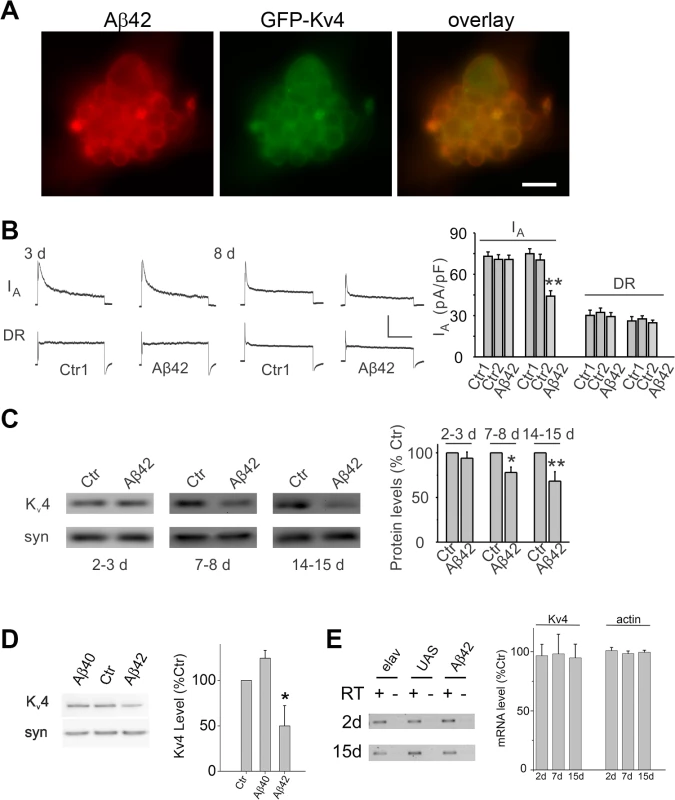

To examine if Aβ42 accumulations seen in these cultures might co-localize with Kv4 channels, we made cultures from elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/UAS-GFP-Kv4 animals and performed co-immunostaining using antibodies against Aβ42 and GFP. Interestingly, after 9 days in culture, Aβ42 seemed to accumulate especially near the membranes of neurons. Fig. 3A shows anti-Aβ42 staining overlapping with GFP-Kv4 labeling, suggesting a direct interaction.

Fig. 3. Expression of Aβ42 decreases Kv4 protein and currents in the intact brain.

(A) Representative neuronal cluster from 9 day old culture from elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/UAS-GFP-Kv4 embryos show co-localization of Aβ42 (red) and GFP-Kv4 (green) immunostaining. Scale bar represents 8.3 μm. (B) Representative Kv4 and Kv2-Kv3 traces (Left), and Kv4 current density quantification (Right) from GFP-labeled MB neurons in UAS-Aβ42/+ (Ctr) and elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/+ (Aβ42) intact brains at 3 and 8 days; Ctr1 and Ctr2 on right correspond to UAS-Aβ42/+ and elav-GAL4;+, respectively. The Kv2-Kv3 DR component was recorded using a prepulse of -45 mV to completely inactivate Kv4 channels, before stepping to a test potential of +50 mV; the Kv4 current was then isolated by subtracting this DR component from the total whole-cell current elicited from a prepulse of -125 mV, stepping to a test potential of +50 mV. Current density was obtained by dividing peak current amplitude by cell capacitance. Kv4 current density in Aβ42 neurons at 8 days were significantly reduced compared to Ctr1 and Ctr2 neurons (P < 0.05, n = 6–13 for each genotype). Scale bars represent 50 pA and 50 ms. (C) Representative immunoblots (Left) and quantitative analyses (Right) of Kv4 protein levels in UAS-Aβ42/+ (Ctr) and elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/+ (Aβ42) heads at 2–3, 7–8, and 14–15 days after eclosion. Protein levels were normalized to the loading control signal from anti-syntaxin (syn) (n = 4 for each group, * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, Student’s t-test). (D) Representative immunoblots (Left) and quantitative analyses (Right) of Kv4 protein from elav (Ctr), elav;;UAS-Aβ40/+ (Aβ40), and elav;UAS-Aβ42/+ heads at 14–15 days AE. (n = 3–4 for each group, * P < 0.05, Student’s t-test indicates significant difference between Aβ40 and Aβ42) (E) Representative blots (Left) and quantitative results (Right) from RT-PCR analyses for Kv4 and actin RNA levels from elav (Ctr), UAS-Aβ42 (UAS), and elav;UAS-Aβ42/+ (Aβ42) flies aged 2, 7, and 15 days AE. Quantitation was performed from RT-PCR results from three independent RNA extractions; RT minus controls were always performed in parallel with RT plus reactions as indicated. No significant differences were seen across the three genotypes. We next examined whether a reduction in the Kv4 current would also be observed in the intact adult brain. Background control lines and transgenic elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/+ flies were aged for 3 or 8 days after eclosion (AE); whole brains were acutely dissected; MB neurons were GFP labeled as described above. No difference in K+ current density was observed at 3 days. At 8 days, however, we found that Kv4 current density was significantly reduced in MB neurons from Aβ42-expressing brains (Fig. 3B). No differences in cell capacitance (Ctrl: 1.9 +/-0.1 pF, Aβ42 : 1.8 +/ - 0.1 pF), resting membrane potential (Ctrl: -52.8 +/ - 2.3 mV, Aβ42: -49.1 +/ - 1.7 mV), or input resistance (Ctrl: 2.5 +/ - 0.1 GΩ, Aβ42 : 2.4 +/ - 0.2 GΩ) were observed between control and Aβ42 neurons. Our results in primary cultures and the intact brain both indicate that the Kv4 current, and not the Kv2-Kv3 DR current, is affected by Aβ42 with age.

Aβ42 Induces Degradation of Kv4 Protein via a Pathway Dependent on Both the Proteasome and Lysosome

To determine if the reduction in Kv4 current is due to a decrease in channel protein, we performed immunoblot analyses on heads from an elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/+ flies compared to background control lines. Steady-state levels of Kv4 protein were not significantly different at 2–3 days AE. At 7–8 days, however, heads from elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/+ flies displayed a decrease in Kv4 protein, compared to controls; this decrease continued to persist for at least 14–15 days AE (Figs. 3C and S2). To test whether the decrease in Kv4 was specific to the expression of Aβ42, we also examined a similar transgenic line generated to over-express a secreted human Aβ40 peptide [16]. We found that steady-state Kv4 protein levels in elav-GAL4;;UAS-Aβ40/+ fly heads were not significantly different from background control lines at 14–15 days AE, in contrast to elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/+ heads (Fig. 3D). These results suggest that Aβ42, but not Aβ40, induces an age-dependent loss of Kv4.

To investigate the mechanism by which Kv4 protein loss occurs in elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/+ flies, we first examined whether mRNA levels of Kv4 were altered by Aβ42 expression. We isolated RNA from elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/+ and background controls, elav;+ and UAS-Aβ42/+, then performed RT-PCR using primers for Kv4. These experiments were performed using flies that were aged 2 days, 7 days, and 15 days AE; RNA extractions from three different pools of aged flies were used. We found no significant difference in Kv4 mRNA levels from 2 to 15 days (Fig. 3E), suggesting that the reduction in Kv4 is not likely to be due to a change in transcript level.

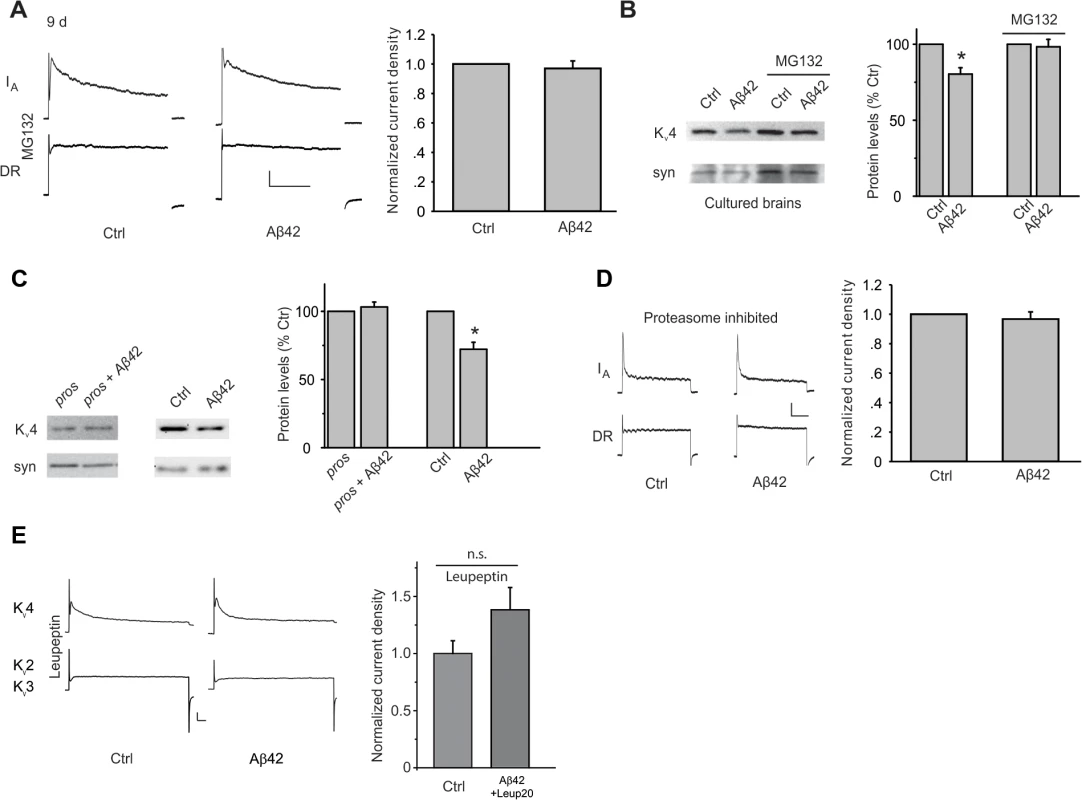

We next tested the hypothesis that Aβ42 induces an increase in Kv4 protein degradation. Since major degradation pathways include the proteasome and/or lysosome, we examined whether Aβ42-induced loss of Kv4 required function of either. To test the possible involvement of the proteasome, neurons dissociated from elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/+ and UAS-Aβ42/+ lines were cultured for 9 days in the presence or absence of MG132, which is known to block proteasome function. We found that MG132 completely blocked the Aβ42-induced decrease in IA (Fig. 4A), suggesting that Aβ42 induces degradation of Kv4 channels via a proteasome-dependent pathway. To test the proteasome’s involvement in situ, we dissected brains at 2 days AE, then maintained them in culture for an additional 4–5 days, as previously performed [25]. Dissected elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/+ and UAS-Aβ42/+ brains were mock and MG132-treated for 4 days. Immunoblot analyses showed that Aβ42 still induced a 22% decrease in Kv4 protein in cultured brains (Fig. 4B). The decrease, however, was completely blocked in the presence of MG132 (Fig. 4B). We also tested the involvement of the proteasome in vivo, using transgenic lines that over-express Pros261 and Prosβ2, dominant-negative mutant forms of the 20S proteasome subunits β6 and β2, respectively [32]. Flies expressing Pros261 and/or Prosβ2 alleles have been shown to exhibit normal proteasome function at 18°C, but severely impaired function when shifted to 29°C [33,34]. We raised elav-GAL4;UAS-Pros261/UAS-Aβ42;UAS-Prosβ2/+ and elav-GAL4;UAS-Pros261/+;UAS-Prosβ2/+ flies at 18°C during development, then shifted newly-eclosed adult flies to 29°C for 7–8 days. We found that when proteasome activity was inhibited, Aβ42 did not induce a decrease in Kv4 protein, as assayed by immunoblot analyses, or a decrease in the Kv4 current, as recorded from MB neurons in the intact brain (Fig. 4C-D). To ensure that an Aβ42-induced decrease in Kv4 could still be expected with the temperature-shift protocol used, we performed similar experiments with elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/+ and UAS-Aβ42/+. Aβ42 expression still induced a decrease of Kv4 protein after a temperature shift to 29°C (Fig. 4C). Together, these results strongly suggest that Aβ42 induces a loss of Kv4 protein by way of a proteasome-dependent pathway.

Fig. 4. Aβ42-induced down-regulation of Kv4 protein is mediated by a proteasome and lysosome-dependent pathway.

(A) Representative traces of separated Kv4 and Kv2-Kv3 currents recorded from MB neurons from UAS-Aβ42/+ (Ctr) and elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/+ (Aβ42) cultures at 9 days, after incubation with MG132 (10 μM). The Kv2-Kv3 DR component was recorded using a prepulse of -45 mV to completely inactivate Kv4 channels, before stepping to a test potential of +50 mV; the Kv4 current was then isolated by subtracting this DR component from the total whole-cell current elicited from a prepulse of -125 mV, stepping to a test potential of +50 mV. Current density was obtained by dividing peak current amplitude by cell capacitance. Quantitative analyses of Kv4 current density shows that MG132 blocked the Aβ42-induced down-regulation of Kv4 (Right; n = 8–9 for each group, ** P < 0.01, Student’s t-test). Scale bars represent 100 pA and 50 ms. (B) Representative immunoblots and quantitative analyses of Kv4 protein levels in cultured brains. The Aβ42-induced decrease in Kv4 is blocked when brains were incubated with MG132 for 4 days. Kv4 levels were normalized to the loading control signal from anti-syntaxin (syn) (n = 3 for each group, * P < 0.05, Student’s t-test). (C) Down-regulation of Kv4 protein by Aβ42 is absent when proteasome activity was inhibited by expression of the dominant temperature-sensitive UAS-Pros261 and UASProsβ2 transgenes. elav-GAL4;UAS-pros261/+;UAS-prosβ2/+ flies (pros), elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/UAS-pros261;UAS-prosβ2/+ flies (pros + Aβ42), UAS-Aβ42/+ (Ctr), and elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/+ (Aβ42) were all raised at 18°C during development, then shifted to 29°C for 7–8 days after adult eclosion. Immunoblot analyses were performed for Kv4, and normalized to syn (Left). For quantitative analyses (Right), n = 4 for each condition, * P < 0.05, Student’s t-test. (D) Aβ42-induced decrease in Kv4 current is also absent by the genetic inhibition of the proteasome described in (C) (right). elav-GAL4;UAS-Pros261/UAS-Aβ42;UAS-Prosβ2/+ and elav-GAL4;UAS-Pros261/+;UAS-Prosβ2/+ flies were raised at 18°C during development, then shifted as newly-eclosed adult flies to 29°C for 7–8 days (n = 4 for immunoblots, and n = 8 for each current recordings). Scale bars represent 25 pA and 50 ms. (E) Representative Kv4 and Kv2–3 currents in Ctrl and elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42 (Aβ42) neurons from cultures treated with 20 μM leupeptin for 8 days. 20 μM leupeptin blocked the Aβ42-induced decrease in Kv4 current density seen in Ctrl neurons. Since turnover of other ion channels and receptors have been shown to be dependent on both the proteasome and lysosome[35–38], we also tested for the possible involvement of the lysosome. We used leupeptin, which is known to block lysosomal function, in wild-type and Aβ42-expressing neuronal cultures. One day after cell cultures were established, leupeptin was added, and cultures were maintained for another 8 days before recording Kv4 currents. We found that leupeptin, at 20 μM, blocked the decrease in Kv4 current in Aβ42-expressing neurons (Fig. 4E). With 10 μM leupeptin, however, Kv4 currents were still decreased in Aβ42-neurons (Fig. 4E), indicating a concentration dependent block of the decrease in Kv4 current seen in Aβ42-neurons. These results suggest that the lysosome, in addition to the proteasome, is involved in Aβ42-induced Kv4 degradation.

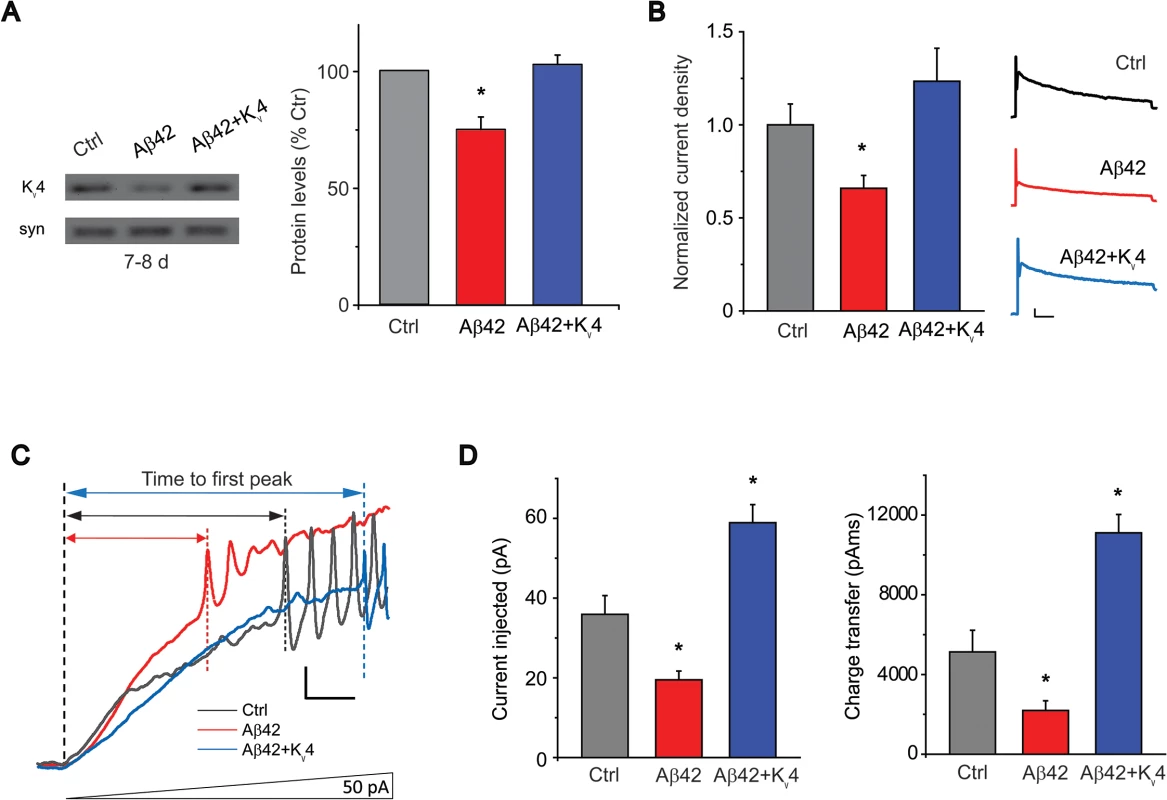

Transgenic Restoration of Kv4 Rescues Hyperexcitability

To test whether we could restore Aβ42-induced hyperexcitability, we generated transgenic lines over-expressing UAS-Kv4 in Aβ42-expressing animals. More than 10 UAS-Kv4 lines were isolated with different insertion sites of the transgene; each line was crossed to an elav-GAL4 driver and expression levels were tested by immunoblot analysis. We selected lines that raised Kv4 protein levels and Kv4 current amplitudes in Aβ42-expressing heads to near wild-type levels (Fig. 5A-B); we refer to these as Aβ42+Kv4 neurons (elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/UAS-Kv4). We then performed current-clamp recordings to determine if restoration of Kv4 reduced excitability in ramp stimulation protocols, as performed in Fig. 1A. We found that in Aβ42+Kv4 neurons, the average current (and charge transfer) required to induce AP firing was significantly increased, compared to neurons from cultures expressing Aβ42 alone, and was quite similar to background control neurons (Fig. 5C-D). These results suggest that the decreased threshold for AP firing observed in Aβ42 neurons is indeed due to the loss of Kv4 channels. We then used these Aβ42+Kv4 lines to test whether downstream cognitive and motor dysfunction would be attenuated.

Fig. 5. Transgenic over-expression of Kv4 in Aβ42-expressing flies restores Kv4 protein levels and normal excitability to neurons.

(A) Immunoblot analyses of UAS-Aβ42/+ (Ctrl), elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/+ (Aβ42), and elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/UAS-Kv4 (Aβ42 + Kv4) fly heads at 7–8 days are shown. Transgenic expression of UAS-Kv4 restores Kv4 protein levels to wild type levels. (n = 3 for each group, * P < 0.05, Student’s t test). (B) Representative Kv4 currents isolated in voltage-clamp mode from primary neurons, from cultures 9 days old, from Ctrl, Aβ42 and elav-GAL4;UASAβ42/UAS-Kv4 (Aβ42+Kv4) flies are shown (Right). The Kv2-Kv3 DR component was recorded using a prepulse of -45 mV to completely inactivate Kv4 channels, before stepping to a test potential of +50 mV; the Kv4 current was then isolated by subtracting this DR component from the total whole-cell current elicited from a prepulse of -125 mV, stepping to a test potential of +50 mV. Current density was obtained by dividing peak current amplitude by cell capacitance. Quantitative analyses (Left) show that Kv4 current density from Aβ42 neurons (194.3 +/- 23.68 pA, n = 9) were significantly smaller than from Ctrl neurons (320.2 +/- 33.52 pA, n = 25). Kv4 current density in Aβ42+Kv4 neurons showed a near complete restoration (334.3 ± 48.97 pA, n = 18). * P < 0.05, Student’s t-test. Scale bars represent 100 pA and 20 ms. (C) Representative current-clamp recordings from Aβ42 and the Aβ42+Kv4 neurons in response to ramped stimulation protocol described in Fig. 1A, show that the time to first peak was significantly prolonged by the restoration of Kv4 to Aβ42-expressing neurons. Scale bar represents 10 mV and 50 ms. (D) Quantification of the average current injected and charge transfer required to elicit the first AP are shown. Both were significantly increased with transgenic restoration of Kv4: 58.9 +/- 4.54 pA, n = 9 (Left), and 11,108.0 +/- 920.49 pAms, n = 9 (Right); note that quantification for Ctrl and Aβ42 values represent the same data set shown in Fig. 1B. * P < 0.05, Student’s t-test. Loss of Kv4 Plays a Critical Role in Aβ42-Induced Learning Defects

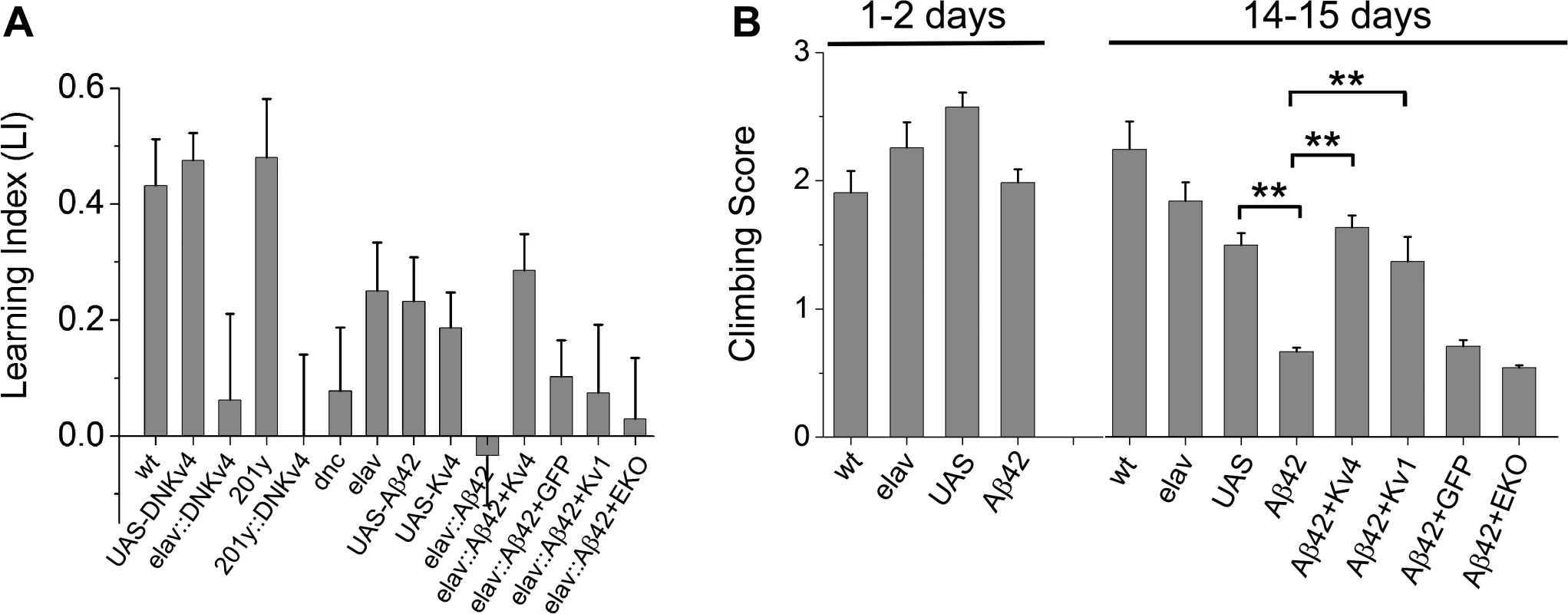

We first investigated whether Aβ42-induced loss of Kv4 would be predicted to affect learning in this fly model. We reasoned that the Aβ42-induced changes observed in our aged late-embryonic cultures were likely to be relevant at larval stages. So, to examine learning, we used an odor-association learning assay with third instar larvae, similar to previously published studies [39]. Larvae were trained to associate a neutral odor (amyl acetate (AM), or 1-octanol (OCT)) with fructose, a natural appetitive attractant. In AM+/OCT - training, larvae were trained to associate AM with fructose, while in AM-/OCT+ training, larvae were trained to associate OCT with fructose (see Materials and Methods). After training, larvae were placed on a test plate with an AM source on one side, and an OCT source on the other side; after 20 minutes, the number of larvae on each half of the plate were counted. Standard preference scores (Pref) for AM and OCT were used to calculate a learning index (LI) for each independent pair of groups that had undergone AM+/OCT - and AM/OCT+ training (see Materials and Methods). We performed two sets of studies: first, to examine whether the loss of Kv4 function alone could lead to learning impairment, and second, to examine the effect of Aβ42 on learning, and to determine if defects would be attenuated by Kv4 expression. Prior to these studies, we first confirmed that all genotypes showed a naïve preference for fructose (S3A Fig.), no preference for AM or OCT (S3B Fig.), and normal chemotaxis towards known attractants (S3C Fig.).

In the first set of studies, we tested whether the loss of Kv4 function alone would affect learning. To do this, we used a transgenic Kv4 dominant-negative line, elav-GAL4;;UAS-DNKv4, that completely eliminates Kv4 function [26]. We found that wild-type and the UAS-DNKv4 background stock performed similarly, showing a learned preference for the odor associated with fructose during training, with a LI of 0.43 +/ - 0.08 and 0.48 +/ - 0.05, respectively (Fig. 6A). In contrast, elav-GAL4;;UAS-DNKv4 larvae showed no preference for either odor after training (LI = 0.06 +/ - 0.15), similar to the known learning mutant dunce (dnc; LI = 0.08 +/ - 0.11) (Fig. 6A). We further tested whether loss of Kv4 function in MBs alone affected learning/memory function. We used the MB driver 201y-GAL4 and found that in 201y-GAL4;UAS-DNKv4 larvae, learning was also impaired (LI = 0.0 +/ - 0.14; Fig. 6A), suggesting that Kv4 function in MBs is especially important for learning.

Fig. 6. Larval olfactory associative learning and locomotion is defective in Aβ42-expressing larvae, and rescued by Kv4.

(A) The following genotypes were trained and tested for learning function: wild-type (wt), UAS-DNKv4 (UAS-DNKv4), elav-GAL4;;UAS-DNKv4 (elav-GAL4::DNKv4), elav-GAL4 (elav), UAS-Aβ42/+ (UAS-Aβ42), UAS-Kv4 (UAS-Kv4), elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/+ (elav::Aβ42), elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/UAS-Kv4 (elav::Aβ42+Kv4), elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/UAS-Kv1 (elav::Aβ42+Kv1), elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/+;UAS-CD8-GFP (elav::Aβ42+GFP), elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/+;UAS-EKO/+ (elav::Aβ42+EKO), dnc1 (dnc), 201y-GAL4 (201y), and 201y-GAL4;UAS-DNKv4 (201y::DNKv4). Learning was tested by training larvae to associate AM or OCT with fructose in the AM+/OCT- or AM-/OCT+ paradigms described in the text and Materials and Methods. After training, larvae were placed on a plain agarose test plate, with AM and OCT sources at opposite sides; after 20 minutes, larvae on each half of the plate were counted. Preference scores and a learning index (LI) were calculated, as described in Materials and Methods (n = 4–15 pairs of groups for each genotype, with one pair consisting of one group for AM+/OCT- training and one group for AM-/OCT+ training; 5 larvae per individual group). elav-GAL4;UAS-DNKv4, 201y-GAL4;UAS-DNKv4, and dnc all showed significantly reduced learning indices, compared to wild-type and background controls. elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/+ also had a significantly reduced LI compared to background controls, which was rescued in elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/UAS-Kv4, but not in elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/+;UAS-CD8-GFP/+, elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/UAS-Kv1, or elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/+;UAS-EKO/+. (B) Locomotor activity was tested in a standard climbing assay on wild-type (wt), elav-GAL4 (elav), UAS-Aβ42/+ (UAS), elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/+ (Aβ42), elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/UAS-Kv4 (Aβ42+Kv4), elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/UAS-Kv1 (Aβ42+Kv1), elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/+;UAS-CD8-GFP/+ (Aβ42+GFP), and elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/+;UAS-EKO/+ (Aβ42+EKO) at 1–2 days and 14–15 days after eclosion, as described in text; each fly was given one point for every two tubes they climbed out of. The mean score of flies from each group (30–35 flies) was calculated; this was then repeated for 5–15 groups for each genotype with averages shown. elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/+ flies showed a significant impairment at 14–15 days, compared with UAS-Aβ42/+ background controls. Co-expression of UAS-Kv4 or UAS-Kv1 rescues this impairment, while expression of UAS-EKO did not. * denotes P < 0.05, Student’s t-test. We next tested whether Aβ42-expressing larvae display learning defects. We compared elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/+ larvae with background control larvae containing either the elav-GAL4 driver or the UAS-Aβ42 transgene alone. Larvae were trained, tested and scored as described above. We found that Aβ42-expressing larvae exhibited a severely impaired LI, compared with background controls (LI = -0.03 +/ - 0.09 for elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/+, LI = 0.23 +/ - 0.08 for UAS-Aβ42/+, P < 0.05; Fig. 6A). We then examined elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/UAS-Kv4 larvae. We found that over-expression of Kv4 rescued learning defects in Aβ42-expressing animals, restoring the LI to 0.29 +/ - 0.06 (p < 0.05; Fig. 6A). Since all genotypes showed a similar naïve preference for fructose, no naïve preference for AM or OCT, and chemotaxis towards known attractants (S3 Fig.), no defects were likely due to impaired sensory transduction.

To test the specificity of the rescue of Aβ42-induced learning defects by Kv4, we also expressed UAS-Kv1, UAS-EKO, or UAS-CD8-GFP, in Aβ42-expressing flies. Kv1 (Shaker) is another A-type K+ channel in Drosophila that represents a multigene subfamily in mammals. EKO is a genetically modified Drosophila Kv1 channel. EKO channels have been altered so that their activation threshold is more hyperpolarized, near EK, and their N-terminal inactivation mechanism has been disabled [40]; expression of EKO has been successfully used as a general suppressor of neuronal activity [40]. We found that the LI of elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/+ larvae (LI = 0.03 +/ - 0.09) was not improved in elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/Kv1 or elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/+;UAS-EKO/+ larvae (LI = 0.075 +/ - 0.12 and 0.03 +/ - 0.10, respectively; Fig. 6A). Expression of UAS-CD8-GFP, a non-channel transmembrane protein, also showed no rescue of Aβ42-induced learning defects (Fig. 6A). Thus, the rescue of Aβ42-induced learning defects by Kv4 appears to be specific, as it could not be replicated with Kv1 or EKO expression. In addition, these results show that expression of another UAS construct (UAS-Kv1, UAS-EKO, UAS-CD8-GFP) did not dilute the effect of UAS-Aβ42 on learning. Altogether, these studies suggest that Aβ42-induced loss of Kv4 is likely to be a critical contributor to downstream learning defects.

Restoration of Kv4 Levels Rescues Locomotor Defects

Aβ42 expression has previously been shown to result in age-dependent climbing defects [16,18]. Interestingly, we have previously shown that loss of Kv4 function in elav;;UAS-DNKv4 flies results in over-excitation of neurons, loss of reliable repetitive firing, and impaired repetitive behaviors, such as climbing [26]. One possibility is that the Aβ42-induced decrease in Kv4 contributes to the age-dependent locomotor deficit of Aβ42-expressing flies. So, we examined whether transgenic restoration of Kv4 was able to rescue the impaired locomotor function seen in Aβ42-expressing flies. Flies were collected over a 2 day period, then aged either 1 or 14 additional days. We used a standard assay that examines the ability of flies to climb against gravity [41,42]; flies’ performance was scored as described (Materials and Methods). At 1–2 days AE, elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/+ flies scored similarly (1.98 +/ - 0.11, n = 10) to background controls (2.25 +/ - 0.20 for elav-GAL4, 2.57 +/ - 0.11 for UAS-Aβ42/+, n = 10; Fig. 6B). In contrast, at 14–15 days AE, elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/+ flies scored significantly lower (0.66 +/ - 0.04, n = 10) than background control lines (1.84 +/ - 0.15 for elav-GAL4, 1.49 +/ - 0.09 for UAS-Aβ42/+, n = 10; Fig. 6B), as expected. We then examined elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/UAS-Kv4 flies at 14–15 days. We found that over-expression of Kv4 increased climbing scores to near wild-type levels (1.63 +/ - 0.09, n = 10, P < 0.01; Fig. 6B). In contrast, expression of EKO channels or CD8-GFP did not significantly improve climbing scores (0.54 +/ - 0.02, n = 10 or 0.71 +/ - 0.05, n = 10, respectively; Fig. 6B). These results suggest that the Aβ42-induced loss of Kv4 channels underlies downstream locomotor defects. Interestingly, over-expression of Kv1 also rescued the Aβ42-induced climbing score (1.37 +/ - 0.60, n = 10; Fig. 6B), suggesting that the A-type channel properties of Kv1 may be able to substitute for Kv4 function in locomotor activity.

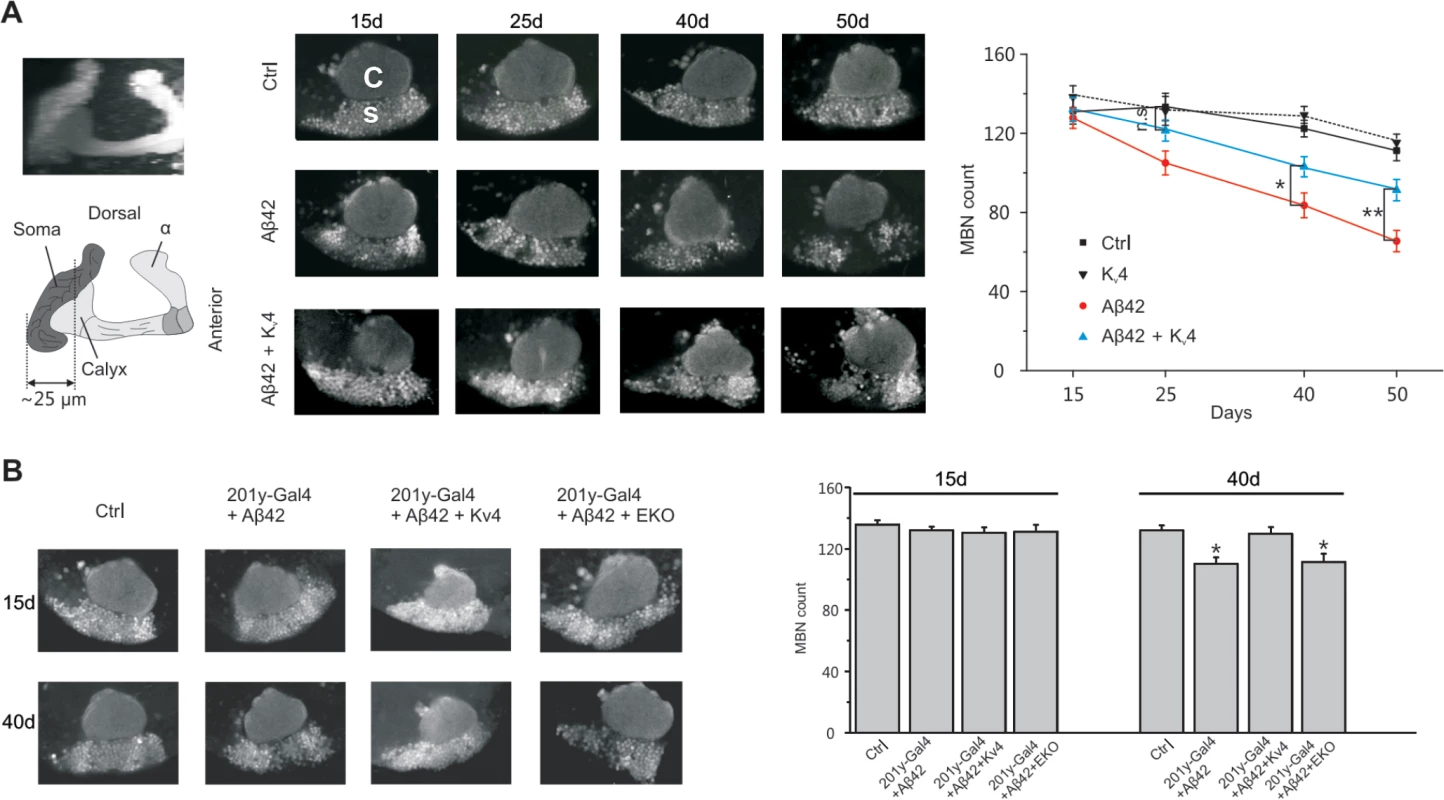

Restoration of Kv4 Slows Aβ42-Induced Neurodegeneration

We next investigated whether raising Kv4 levels in Aβ42 neurons to near wild-type levels, as described above, would attenuate the age-dependent neuronal loss that has been reported to begin at 25 days AE[16]. While secreted Aβ42, and Kv4, were over-expressed pan-neuronally, we assayed for cell loss specifically in the MBs, using the GFP.S65T.T10 transgene. We counted GFP-labeled MB neurons from: 1) a background control line (elav-GAL4), 2) the Aβ42-expressing line (elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/+), and 3) an Aβ42+Kv4 line (elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/UAS-Kv4). GFP-labeled MB neurons in the intact brain were imaged by confocal microscopy, and cell bodies were counted from images taken at a fixed position (see Fig. 1A) at 15, 25 40, and 50 days AE (aged at 22–23°C). As expected, cell numbers progressively decreased from 25 to 50 days in flies expressing Aβ42 (Fig. 7A). In the Aβ42+Kv4 line, however, the onset of cell loss was delayed, with no significant degeneration at 25 days (Fig. 7A); at 50 days, cell loss was attenuated by 58% (Fig. 7A). Expression of Kv4 in a wild-type background (elav-GAL4;UAS-Kv4/+) did not increase cell survival (Fig. 7A), suggesting that amelioration of neurodegeneration in Aβ42+Kv4 brains was indeed due to the restoration of Kv4.

Fig. 7. Restoration of excitability in Aβ42-expressing flies ameliorates age-dependent neuronal loss in MBs.

(A) Converged confocal z-stack images of a typical mushroom body from the transgenic line, elav-GAL4;;GFP.S65T.T10/+ (Left, Top), and a corresponding diagram with regions containing cell bodies, dendrites (in calyx), and axons shown (Left, bottom); MB neurons were GFP labeled by the GFP.S65T.T10 transgene (regardless of GAL4 driver present, see text) and counted from single images taken 25 μm from the posterior-most edge of MB, as depicted by the dotted line shown. Representative confocal images used for counting neurons are shown from elav-GAL4;;GFP.S65T.T10/+ (Ctr), elav-GAL4;UAS-Kv4/+;GFP.S65T.T10/+ (Kv4), elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/+;GFP.S65T.T10/+ (Aβ42), and elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/UAS-Kv4;GFP.S65T.T10/+ (Aβ42 + Kv4) flies at indicated ages: 15, 25, 40 and 50 days AE (Middle); in confocal images, the calyx (C) is seen above the region containing MB cell somas (s). Quantitative analyses show that restoration of normal excitability by transgenic UAS-Kv4 expression significantly increases neuronal survival at 40 and 50 days, delaying the onset of neurodegeneration (no significant (n.s,) difference between Ctr and Aβ42 + Kv4 at 25 d) (Right). (n = 6–7 for each group, * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, Student’s t-test). (B) Local expression of UAS-Aβ42 was induced using the MB driver 201y-GAL4. Representative confocal images and quantification, as described in (A), are shown from 201y-GAL4;GFP.S65T.T10/+ (Ctr), 201y-GAL4/UAS-Aβ42/+;GFP.S65T.T10/+ (201y-Gal4+Aβ42), 201y-GAL4/UAS-Aβ42; GFP.S65T.T10/UAS-Kv4 (201y-Gal4+Aβ42+Kv4), and 201y-GAL4/UAS-Aβ42;UAS-EKO/GFP.S65T.T10 (201y-Gal4+Aβ42+EKO) heads at 15 and 40 days after eclosion. Local expression of Aβ42 results in a significant reduction in MBNs at 40 days (110.30 +/- 4.03), compared to Ctr (132.10 +/- 3.17), which is rescued by Kv4 expression (129.40 +/- 4.18), but not expression of EKO (111.30 +/- 4.76); n = 8–9 brains for each condition, *P < 0.05, Student’s t-test. We also tested whether expression of Aβ42 exclusively in MB neurons would induce local degeneration, and if so, whether this degeneration was also due to hyperactivity generated by the loss of Kv4. We used the MB GAL4 transgene, 201y-GAL4, to drive expression of UAS-Aβ42, with and without UAS-Kv4. In brains from 40 day old flies, we found that the number of MB neurons was reduced by ∼17%, compared to brains from a background control line (Fig. 7B). When UAS-Kv4 was co-expressed with UAS-Aβ42, however, the number of MB cells were similar to controls (Fig. 7B). We also tested if expression of UAS-EKO would attenuate Aβ42-induced MB degeneration. The 201y-GAL4 transgene was used to drive MB expression of UAS-Aβ42, with and without UAS-EKO; flies were aged for 15 and 40 days, then GFP-labeled MB neurons were counted. We found that EKO did not slow Aβ42-induced MB degeneration (Fig. 7B), suggesting that the loss of Kv4 function, in particular, plays a role in this neuronal degeneration.

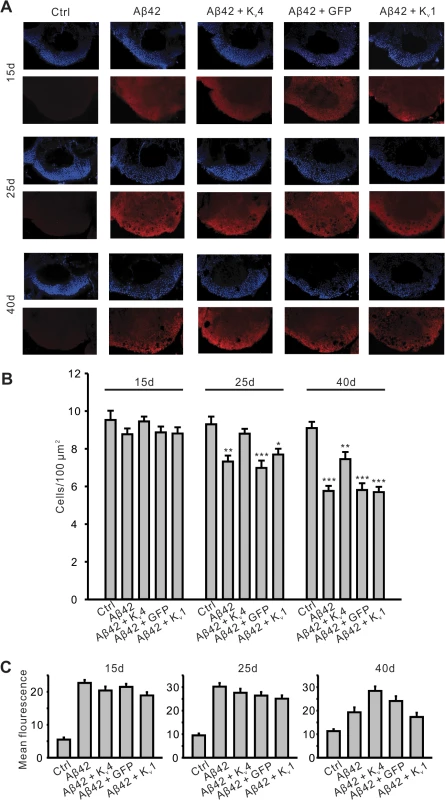

To further examine the specificity of the role of Kv4 in Aβ42-induced MB degeneration, we investigated the effect of expressing a general UAS construct, UAS-GFP, or the other A-type K+ channel in Drosophila, UAS-Kv1. In addition, we used another method for quantifying MB neurons and co-labeled for Aβ42 expression. We dissected brains from elav;UAS-Aβ42/+ flies with and without UAS-Kv4, UAS-GFP, or UAS-Kv1 transgenes at 15, 25, and 40 days AE. Brains were co-labeled with DAPI to count cell bodies, and an anti-Aβ42 antibody to compare levels of Aβ42. Brains were imaged by confocal microscopy, as described above, and DAPI-positive cell density was quantified in the MB (Fig. 8A). No cell loss was seen at 15 days AE. Similar to our results quantifying GFP-positive MB cells, we detected a significant loss of DAPI-positive MB cells first at 25 days AE (P <. 01), then continuing at 40 days AE (P < 0.001, Fig. 8B). Over-expression of Kv4 delayed the onset, and slowed, the ensuing degeneration (Fig. 8B). Since expression of UAS-GFP did not attenuate or slow the Aβ42-induced degeneration at 25 or 40 day AE (Fig. 8B), it is unlikely that inclusion of an additional UAS target site alone leads to decreased expression of Aβ42 and apparent rescue of neurodegeneration. Indeed, quantification of Aβ42 revealed no loss of Aβ42 expression in Aβ42+Kv4 MBs (Fig. 8C).

Fig. 8. Pan-neuronal expression of Kv4 slows the onset and severity of Aβ42-induced neurodegeneration.

(A) Representative confocal images, from MB position described in Fig. 7, show nuclear (DAPI) staining (upper panels, blue) from five genotypes, including UAS- Aβ42/+ (Ctr), elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/+ (Aβ42), elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/UAS-Kv4 (Aβ42+Kv4), elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/UAS-GFP (Aβ42+GFP) and elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/UAS-Kv1 (Aβ42+Kv1). Co-immunolabeling for Aβ42 is shown (lower panels, red) from these genotypes. Brains were dissected and labeled from flies aged 15 days (15d), 25 days (25d) and 40 days (40d) AE. Note that Aβ42 immunostaining is clearly seen in all the genotypes except Ctr. (B) Quantification of cell density (DAPI-positive) from confocal images described in (A). Note that there is significant cell loss in Aβ42, Aβ42+GFP, and Aβ42+Kv1 flies at 25d, but not in Aβ42+Kv4. n = 6–8 for each genotype, * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001, Student’s t-test. (C) Relative anti-Aβ42 signal was quantified in the same aged genotypes described in (A); background fluorescence is reflected in Ctr samples. Note that no significant difference in Aβ42 signal was seen in Aβ42+Kv4 brains, compared to Aβ42 at 15 and 25 days AE; at 40d AE, Aβ42+Kv4 brains show an increase in Aβ42 signal; quantification, however, was difficult due to the number of degenerative “holes” seen in confocal sections at this age. n = 6–8 for each genotype. All data are expressed as means ± SEM. Interestingly, expression of UAS-Kv1 resulted in increased cell survival in Aβ42-expressing animals at 25 days AE, but not at 40 days AE (Fig. 8B). These results suggest that A-type K+ channel function from Kv1 can help decrease the severity of initial degeneration, perhaps by ameliorating hyperexcitation. Also interestingly, we found that loss of Kv4 function alone did not induce neurodegeneration, as observed by DAPI-positive MB cell density in elav;;UAS-DNKv4 compared to a background control line at 25 and 40 days AE (Fig. 9). Altogether our results suggest that while the loss of Kv4 channels, and ensuing hyperexcitability, are key factors that exacerbate neurodegeneration, the Aβ42-induced reduction of Kv4 channels is not sufficient to trigger degeneration.

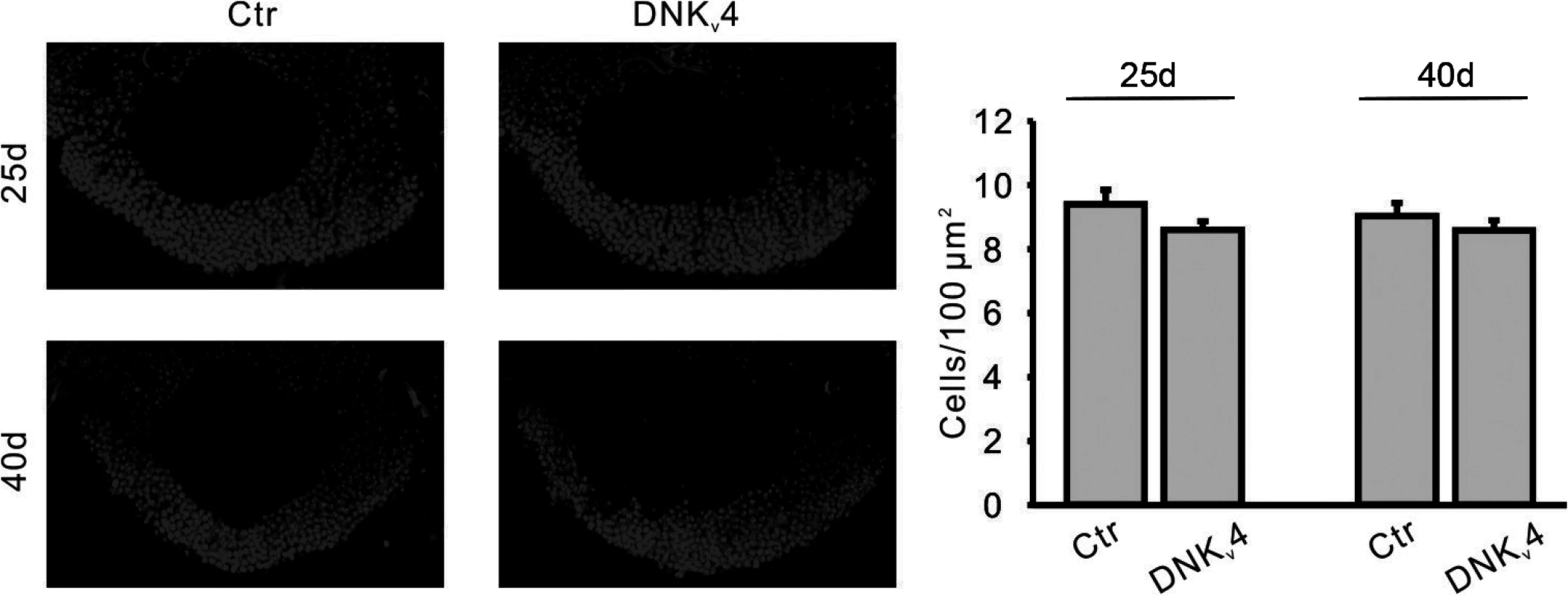

Fig. 9. No significant MB cell loss is found in the DNKv4 transgenic line.

Representative images (Left) and quantification (Right) of nuclear (DAPI) staining in MBs of UAS-DNKv4 (Ctr) and elav-GAL4;UAS-DNKv4 (DNKv4) at 25 and 40 days AE. MB orientation and position of confocal image as described in Fig. 7. No significant difference in cell density was seen in DNKv4 brains compared to controls. n = 6 for each genotype. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. Aβ42-Induced Loss of Kv4 Contributes to Premature Death

Since elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/+ flies have been shown to exhibit a shortened lifespan [16–18], we examined whether hyperactivity, generated by the loss of Kv4, might also contribute to this phenotype. We first examined whether loss of Kv4 function alone would affect lifespan. We compared two different insertions of UAS-DNKv4 (#14 and #20), and found that elav-GAL4;;UAS-DNKv4 survivorship was significantly decreased, with a median age of 31 and 47 days, compared to 67 and 82 for respective controls (P < 0.0001 by log-rank analyses; Fig. 10A). We then restricted expression of UAS-DNKv4 to the adult to eliminate effects from loss of Kv4 function during development. To do this, we used the UAS-GAL4-GAL80ts system [43] to induce expression of UAS-Aβ42 in the nervous system only after adult eclosion. In this system, the GAL80 protein inhibits GAL4 function and therefore Aβ42 expression. We used the tub-GAL80ts transgene, which expresses a temperature-sensitive GAL80ts protein under the control of the tubulin promoter; at 18°C, the GAL80ts protein is functional, while a shift to 30°C renders the GAL80ts protein non-functional. Flies containing elav-GAL4, tub-GAL80ts, and UAS-DNKv4 transgenes (elav-GAL4;tub-GAL80ts;UAS-DNKv4) were raised at 18°C to prevent expression of UAS-DNKv4, then shifted to 30°C to induce expression of DNKv4 for the lifespan of the adults. Longevity of elav-GAL4;tub-GAL80ts;UAS-DNKv4 flies was significantly shorter (median age of 32 days; p < 0.0001) than wild-type (median age of 39 days) and background control (median age of 37 days) lines under similar conditions (Fig. 10B). These results suggest that Kv4 function in the adult is likely to play a role in longevity.

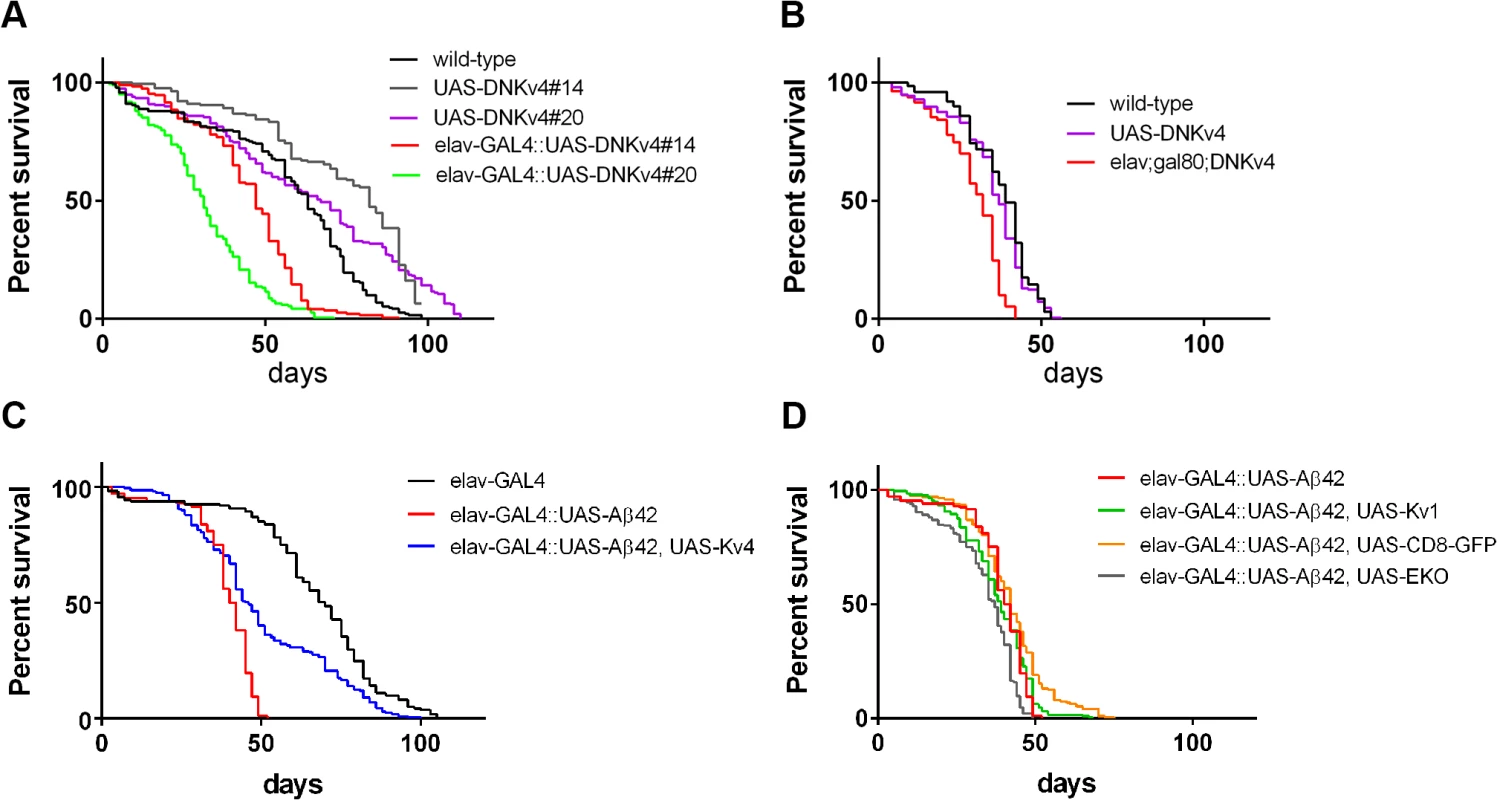

Fig. 10. Premature death is partially rescued by expression of Kv4 in Aβ42-expressing flies.

(A-D) Longevity assays, using populations of ∼200 male flies, for indicated genotypes (see Materials and Methods). (A) Survival plots for wild-type, two different transgenic insertions of UAS-DNKv4 (#14 and #20), and elav-GAL4;;UAS-DNKv4 (elav-GAL4::UAS-DNKv4) lines are shown. Neuronal expression of UAS-DNKv4 leads to a significantly reduced (P < 0.0001 by log-rank analyses) lifespan at 25°C compared to UAS background controls. (B) Longevity assays performed for flies raised at 18°C during development, then shifted to 30°C for the entirety of the adult lifespan. Induced expression of DNKv4 resulted in a significantly reduced lifespan (elav-GAL4;tub-GAL80ts;UAS-DNKv4; median age of 32 days), compared to wild-type (median age of 39 days) and UAS-DNKv4 (median age of 37 days); significance of P < 0.0001 by log-rank analyses. (C-D) Survival plots for elav-GAL4;+ (elav-GAL4), elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/+ (elav-GAL4::UASAβ42), elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/UAS-Kv4 (elav-GAL4::UASAβ42,UAS-Kv4), elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/UAS-Kv1 (elav-GAL4::UASAβ42,UAS-Kv1), elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/+;UAS-CD8-GFP/+ (elav-GAL4::UASAβ42,UAS-CD8GFP), and elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/+;UAS-EKO/+ (elav-GAL4::UASAβ42,UAS-EKO); all of these assays were performed at 25°C. elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/+ flies show a severely reduced lifespan (median age of 41 days) at 25°C, compared with the UAS-Aβ42/+ background control (median age of 70 days; significance of P < 0.0001 by log-rank analyses). elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/UAS-Kv4 flies showed a partial rescue of lifespan (median age of 46 days; P < 0.0001 by log-rank and Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon analyses), while elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/+;UAS-EKO/+, elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/Kv1, and elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/+;UAS-CD8-GFP/+ flies did not show a significant improvement in lifespan from elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/+ flies. We next compared the longevity of elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/+ flies with background control lines. We found that elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/+ flies have a greatly shortened lifespan (median age of 41 days) compared to the control line (median age of 70 days, p < 0.0001; Fig. 10C). We then tested elav-GAL4;UAS-Aβ42/UAS-Kv4 flies to see if restoration of normal excitability would attenuate premature death induced by Aβ42. Over-expression of Kv4 in Aβ42-expressing flies resulted in a small, but significant, increase in lifespan (median age of 46 days, p < 0.05; Fig. 10C). Over-expression of Kv1, EKO, or CD8-GFP, however, did not significantly increase the lifespan of Aβ42-expressing flies (median ages of 37, 39, and 42 days, respectively; Fig. 10D). These results further support the partial, yet specific, rescue of premature death by Kv4 expression.

Discussion

Aβ-induced hyperexcitability is indeed intriguing, with interesting implications especially for seizure-like activity and epilepsy, which are potentially associated with AD [11,15,44,45]. Little, however, has been done previously to determine whether Aβ-induced hyperactivity contributes to downstream behavioral pathologies. Recent studies, however, have suggested that neuronal hyperactivity may precede neurological dysfunction [46] and may be improved by pharmacologically reducing activity [44]. In this study, we show, in cultured neurons and in the intact brain, that Kv4 channels are specifically down-regulated by Aβ42 expression, while other K+ currents (eg. Kv2 and Kv3) remain unaltered. The resulting increase in neuronal excitability was present in the adult brain at an age (8 days AE) before the appearance of locomotor (14–15 days AE) and learning defects (14 days AE; ref), and before the onset of neurodegeneration (25 days AE), supporting the hypothesis that hyperactivity precedes and contributes to these downstream pathologies. We then show that increasing Kv4 channel levels in Aβ-expressing animals restores normal excitability to neurons, and as a result, completely rescues learning and locomotor defects, slows neurodegeneration, and slightly increases lifespan. It is significant to note that the expression of a UAS-GFP or UAS-CD8-GFP transgene did not rescue any of these pathologies, suggesting that any rescue effects by UAS-Kv4 were not simply due to the introduction of another UAS target for GAL4 that would dilute the expression of Aβ42; indeed, quantification of Aβ42 was not any lower in Aβ42+Kv4 flies. In future studies, it will be interesting to examine the temporal requirement for reducing excitability with Kv4 expression; for example, is early hyperexcitability more “toxic” to the system than later stage hyperexcitability?

Although specificity of rescue by Kv4 varied from one pathology to another, the genetically engineered EKO channel that acts as a general activity inhibitor did not ameliorate any of the cognitive, motor, or survival deficits tested. This suggests that general dampening of excitability was not sufficient to replace Kv4 loss. Kv1, the other A-type K+ channel present in Drosophila, however, was able to rescue Aβ42-induced locomotor dysfunction, but, interestingly, not learning or premature death. These results are consistent with the fact that Kv1 and Kv4 share some, but certainly not all, biophysical properties. For example, Kv4 channels have a much more hyperpolarized voltage-operating range than Kv1 channels, making them much more likely to play roles at subthreshold potentials [20,21]. Also, while both Kv4 and Kv1 channels display fast inactivation, the inactivation rate is voltage-independent for Kv4 channels and voltage-dependent for Kv1 channels[20,21]. Finally, the subcellular localization of Kv4 and Kv1 channels are thought to be distinct, with Kv4 channels restricted to dendrites and cell bodies, and Kv1 channels localized in axons and nerve terminals.

We also examined whether the loss of Kv4 function alone was sufficient to lead to cognitive and motor pathologies. Previously, we had shown that expression of a dominant-negative Kv4 subunit, DNKv4, results in the elimination of the Kv4 current[26]. Loss of Kv4 function led to increased excitability and locomotor deficits[26,47,48]. In the present study, we found that expression of DNKv4 also induced learning defects and a shortened lifespan, consistent with a key role for the Aβ42-induced reduction in Kv4 in these downstream pathologies. In mammalian systems, Kv4.2 has been shown to play a role in the induction of long-term potentiation (LTP) [49], and hippocampal dependent learning/memory defects [50]. Loss of Kv4 function alone, however, did not induce any significant neurodegeneration, suggesting that while Aβ42-induced loss of Kv4 exacerbates degeneration, it is not sufficient to trigger neurodegenerative pathway(s).

Previous reports over the years have shown different effects of Aβ on A-type K+ currents in vitro, with some identifying decreases in IA [51,52] and others reporting increases in IA [4,53–57]. Differences between these studies are likely to be due to a variety of factors including the species of Aβ tested (eg. Aβ1–40, Aβ1–42, Aβ25–35; some studies finding clear differences with different Aβ species [56], the cell type examined (eg. HEK cells, hippocampal neurons, or cortical neurons), and the time course of the effect (eg. from seconds to days in different studies). For example, the Aβ species applied, the concentration used, and time incubated with cells all affect the assembly state of Aβ, which has also been proposed to have differential downstream effects on K+ currents [4,51] and excitability/activity [8,12]. In the future, it will be interesting to see how effects on Kv4 develop, and possibly change, throughout the assembly of Aβ42 from monomers to oligomers, protofibrils, and mature fibrils in vivo.

Much remains to be understood about the mechanism by which Kv4 channels are lost in response to Aβ42 expression. In this study, pharmacological and genetic approaches suggest a degradation pathway for Kv4 that depends on both the proteasome and lysosome, similar to the EGF receptor [35,36]. This scenario is likely to be complicated since previous studies have shown that Aβ directly inhibits the proteasome [58], and that clearance of Aβ depends on the proteasome [59–62]. Further study is needed to understand how Kv4 channels are targeted for turnover by Aβ42, and what other component(s) are involved.

Further study is also needed to unravel specific mechanisms by which Kv4 channels function in downstream Aβ42 pathologies. For example, how does the loss of Kv4 exacerbate neurodegeneration? One possibility is that cell death is induced by an “excitotoxic” pathway due to excess Ca2+ entry, and ultimately, necrosis. Interestingly, previous studies have shown that Aβ42 induces an increase in various K+ currents that are linked to cell death in vitro [63–65], consistent with evidence that efflux of K+ is required as an early step in apoptosis [66]. While it is not clear how to reconcile these findings with ours, it does seem that proper K+ homeostasis is critical for neuronal survival. The role of Kv4 in lifespan, however, is complex, given that neurodegeneration, learning/memory formation, and locomotor activity all contribute to survival. The partial to full rescue of multiple Aβ42-induced pathologies by Kv4, however, underscores the importance of the loss of Kv4 in vivo and suggests that Kv4 is a critical target of Aβ42 in this model, and perhaps in AD.

Materials and Methods

Fly Stocks

We used previously generated transgenic lines: UAS-GFP-Kv4 [67,68], UAS-Aβ40 and UAS-Aβ42/CyO [16–18], GFP.S65T.T10 [30,31], UAS-Pros261;UAS-Prosβ2 [32], and UAS-EKO [40]. For UAS-Kv4, the wild-type Shal2 isoform was subcloned into the pENTR1A vector (Gateway pENTR vectors, Invitrogen), then recombined in vitro using lambda integrase into the pTW destination vector (Drosophila Gateway Vector Collection, available through the Drosophila Genomics Resource Center), generating the pUAST-Shal2 transformation vector. Microinjection with transposase into w1118 embryos to generate transgenic lines was performed by Rainbow Transgenics (Camarillo, CA), then mapped and balanced by standard procedures. For behavioral studies, fly lines were successively outcrossed at least five times before use.

Whole-Brain and Embryonic Neuronal Cultures

For whole-brain cultures, flies (2 days after eclosion) were anaesthetized, and the brains were quickly dissected, as reported previously [25]. We incubated the cultures in a humidified chamber at room temperature and refreshed the culture medium (18% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin in Schneider’s Drosophila culture medium) every 12 hours. 10 brains were sonicated for each immunoblot sample. For embryonic neuronal cultures, single embryos aged 5–6 hours (at room temperature) were dissociated in 20 μL drops of culture medium, as previously described [20,21,25].

Electrophysiology

Whole-cell recordings were performed in perforated patch-clamp configuration by adding 400–800 μg/ml Amphotericin-B (Sigma-Aldrich) in the pipette, as reported previously [25,26]. For current-clamp recordings, we used external solution (in mM):NaCl, 140; KCl, 2; HEPES, 5; CaCl2, 1.5; MgCl2, 6, with pH 7.2. For K+ current recordings in cultured MB neurons, we used external solution (in mM): Choline-Cl, 140; KCl, 2; MgCl2, 6; HEPES, 5, with pH 7.2. For K+ current recordings from GFP-labeled MB neurons in the intact brain, we exchanged culture medium to the external solution (in mM): NaCl, 110; KCl, 2; MgCl2, 6; glucose, 5; NaHCO3, 20; NaH2PO4. Solution was continuously bubbled with carbogen (5% oxygen and 95% carbon dioxide) throughout recording; pH was set at 7.2. TTX (1 μM) and nifedipine (10 μM) were added to the external solution to block Na+ and Ca2+ currents. Electrodes were filled with internal solution (in mM): K-gluconate, 120; KCl, 20; HEPEs, 10; EGTA, 1.1; MgCl2, 2; CaCl2, 0.1, with pH 7.2. We performed all recordings at room temperature. Electrode resistances for all recordings were 5–10 MΩ. Gigaohm seals were obtained for whole-cell recordings.

For analyses shown in Fig. 1D, the correlation coefficient (CC) between the membrane potential and the latency to the first AP was examined. Calculation of this CC was performed as a Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient. The CC is defined by CC = SXY /σXσY, where σX and σY are the standard deviations (SDs) of the samples, and SXY is the sample covariance of X and Y. Here, X and Y represent the membrane potential and AP latency. The CC for membrane potential and AP latency in wild-type and Aβ42 neurons were quantified, similar to a previous study [69].

Imaging and Immunoblot Analyses

For fly brain imaging, adult brains were dissected in phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.2), and fixed for 20 min in 4% paraformaldehyde, as previously described [67]. The isolated brains were washed in phosphate buffer for 5 min, 4 times. We either mounted the brains on the coverslips and captured the images on the same day (for pan-neuronal expression of Aβ42), or blocked in 5% goat serum for 1 hour and immunolabeled with anti-GFP (1 : 1000) or Anti-Aβ42 (Anti-β-Amyloid (1–42) Rabbit pAb, Calbiochem) in PBST at 4°C overnight (for experiments using the 201y-GAL4 driver). Brains were washed in PBST (5 min, 4 times) and then incubated with secondary antibody for 1 hour at room temperature; brains were washed (5 min, 4 times), then mounted (with DAPI) and imaged. Images were obtained using a Zeiss LSM 510 confocal microscope; images were processed and analyzed using Photoshop CS2 and Volocity v.6 software (Perkin Elmer).

Neuronal and Aβ42 quantification. The number of GFP-labeled MB cells and DAPI-labeled cells at MB area were blindly counted by three independent investigators. To quantitate cell density, we chose regions of interest (ROIs) in the area of MB cell bodies of ∼400 μm2, and used 3 ROIs from each confocal image. For Aβ42 quantification, grey values of labelled anti-Aβ42 were determined after subtracting the background values, which were taken from non-immunostained brain images. Commonly, the MB area (cell bodies) 1200 μm2 in a single section (one from half brain, and two from the whole brain) were picked up for data collection and all data were pooled from around 6–8 brains for each genotype.

For immunoblot analyses, we used primary antibodies at the indicated concentrations, overnight at 21–23°C: anti-Kv4 (1 : 100;[68], anti-syntaxin (1 : 100; 8C3 from Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, University of Iowa).

RT-PCR

Flies were collected, aged at 25°C, and stored at -80°C until ready to extract total RNA. TRIZOL RNA isolation procedure (Invitrogen/Life Science) was used to extract total RNA following homogenization of liquid nitrogen chilled flies in 1.5 ml RNase/DNase–free Eppendorf tubes with 1.5 ml RNase/DNase – free pestle (KONTES-Kimble Chase LLC). The quantity and quality of total RNA was analyzed by NanoDrop, and agarose gel electrophoresis. To eliminate genomic DNA, RNA samples were treated with DNase I. DNase I treated RNA (1 μg) was used as a template to synthesize first-strand cDNA by Superscript II RT (Invitrogen/ Life Science). Kv4 specific primers were used for standard PCR. Sense primer: AGA ACG GGG ATC AGA ATC TGC A, anti-sense primer: CGG TGG CAA AGA TGA TAA TGG. The quantity of cDNA was measured by Image J following agarose gel electrophoresis. Quantification was averaged over three different total RNA extracts.

Learning/Memory Assays

Larvae were trained in groups of 5. In each training cycle, larvae were: 1) transferred to an “association plate” in which one of the odors is paired with an agarose-fructose (FRU) substrate for one minute, 2) moved to an agarose-only rest plate one minute, 3) moved to an agarose-only plate with the second odor, and 4) moved to an agarose-only rest plate; 10 such training cycles were performed. After training, larvae were placed on an agarose-only test plate with an AM source on one side, and an OCT source on the other side; after 20 minutes, the number of larvae on each half of the plate were counted. 5–15 groups were assayed for each genotype. Standard preference scores and learning indices were calculated as described in [39]. As an example, the preference score for AM (PREFAM), and the learning index (LI) were calculated as shown:

PREFAM = (number of larvaeAM – number of larvaeOCT)/number of larvaeTOTAL

LI = (PREFAM+/OCT- – PREFAM-/OCT+)/2

Given: number of larvaeAM or larvaeOCT indicates the number of larvae on the AM or OCT, half or the test plate, respectively; PREFAM+/OCT- or PREFAM-/OCT+ indicates the preference scores after either AM+/OCT - or AM-/OCT+ training, respectively.

Locomotion Assays

30–35 males in a 12.4 cm tall tube were allowed to climb upwards for 30 seconds into a second tube inverted on top of the first. The flies that successfully climbed into the second tube were given 30 seconds to climb from the bottom of the tube into a third tube. This process was continued through ten successive tubes and measured by a countercurrent distribution [41]; each fly was given a score of 0.5 for each tube that it climbed out of, similar to [42]. 5–15 assays, with ∼30–35 naïve flies, were performed for each genotype tested.

Lifespan Analyses

For each genotype, a total population of 200 newly-eclosed male flies were collected and housed in food vials (10 flies/vial) at the indicated temperatures. Food vials were changed every 2–3 days and the number of dead/surviving flies was counted during each change. Log-rank statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 6 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA).

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. Glenner GG, Wong CW (1984) Alzheimer's disease: initial report of the purification and characterization of a novel cerebrovascular amyloid protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 120 : 885–890. 6375662

2. Tanzi RE, Bertram L (2005) Twenty years of the Alzheimer's disease amyloid hypothesis: a genetic perspective. Cell 120 : 545–555. 15734686

3. Walsh DM, Selkoe DJ (2004) Deciphering the molecular basis of memory failure in Alzheimer's disease. Neuron 44 : 181–193. 15450169

4. Ramsden M, Plant LD, Webster NJ, Vaughan PF, Henderson Z, et al. (2001) Differential effects of unaggregated and aggregated amyloid beta protein (1–40) on K(+) channel currents in primary cultures of rat cerebellar granule and cortical neurones. J Neurochem 79 : 699–712. 11701773

5. Hsieh H, Boehm J, Sato C, Iwatsubo T, Tomita T, et al. (2006) AMPAR removal underlies Abeta-induced synaptic depression and dendritic spine loss. Neuron 52 : 831–843. 17145504

6. Kamenetz F, Tomita T, Hsieh H, Seabrook G, Borchelt D, et al. (2003) APP processing and synaptic function. Neuron 37 : 925–937. 12670422

7. Palop JJ, Chin J, Roberson ED, Wang J, Thwin MT, et al. (2007) Aberrant excitatory neuronal activity and compensatory remodeling of inhibitory hippocampal circuits in mouse models of Alzheimer's disease. Neuron 55 : 697–711. 17785178

8. Busche MA, Chen X, Henning HA, Reichwald J, Staufenbiel M, et al. (2012) Critical role of soluble amyloid-beta for early hippocampal hyperactivity in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109 : 8740–8745. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206171109 22592800

9. Busche MA, Eichhoff G, Adelsberger H, Abramowski D, Wiederhold KH, et al. (2008) Clusters of hyperactive neurons near amyloid plaques in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Science 321 : 1686–1689. doi: 10.1126/science.1162844 18802001

10. Kuchibhotla KV, Goldman ST, Lattarulo CR, Wu HY, Hyman BT, et al. (2008) Abeta plaques lead to aberrant regulation of calcium homeostasis in vivo resulting in structural and functional disruption of neuronal networks. Neuron 59 : 214–225. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.06.008 18667150

11. Minkeviciene R, Rheims S, Dobszay MB, Zilberter M, Hartikainen J, et al. (2009) Amyloid beta-induced neuronal hyperexcitability triggers progressive epilepsy. J Neurosci 29 : 3453–3462. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5215-08.2009 19295151

12. Hartley DM, Walsh DM, Ye CP, Diehl T, Vasquez S, et al. (1999) Protofibrillar intermediates of amyloid beta-protein induce acute electrophysiological changes and progressive neurotoxicity in cortical neurons. J Neurosci 19 : 8876–8884. 10516307

13. Brown JT, Chin J, Leiser SC, Pangalos MN, Randall AD (2011) Altered intrinsic neuronal excitability and reduced Na+ currents in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging 32 : 2109 e2101–2114.

14. Palop JJ, Mucke L (2009) Epilepsy and cognitive impairments in Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol 66 : 435–440. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.15 19204149

15. Verret L, Mann EO, Hang GB, Barth AM, Cobos I, et al. (2012) Inhibitory interneuron deficit links altered network activity and cognitive dysfunction in Alzheimer model. Cell 149 : 708–721. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.046 22541439

16. Iijima K, Liu HP, Chiang AS, Hearn SA, Konsolaki M, et al. (2004) Dissecting the pathological effects of human Abeta40 and Abeta42 in Drosophila: a potential model for Alzheimer's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101 : 6623–6628. 15069204

17. Finelli A, Kelkar A, Song HJ, Yang H, Konsolaki M (2004) A model for studying Alzheimer's Abeta42-induced toxicity in Drosophila melanogaster. Mol Cell Neurosci 26 : 365–375. 15234342

18. Iijima K, Chiang HC, Hearn SA, Hakker I, Gatt A, et al. (2008) Abeta42 mutants with different aggregation profiles induce distinct pathologies in Drosophila. PLoS One 3: e1703. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001703 18301778

19. Brand A, Perrimon N (1993) Targeted gene expression as a means of altering cell fates and generating dominant phenotypes. Development 118 : 401–415. 8223268

20. Tsunoda S, Salkoff L (1995b) The major delayed rectifier in both Drosophila neurons and muscle is encoded by Shab. Journal of Neuroscience 15 : 5209–5221. 7623146

21. Tsunoda S, Salkoff L (1995a) Genetic analysis of Drosophila neurons: Shal, Shaw, and Shab encode most embryonic potassium currents. Journal of Neuroscience 15 : 1741–1754. 7891132

22. Lee D, O'Dowd DK (2000) cAMP-dependent plasticity at excitatory cholinergic synapses in Drosophila neurons: alterations in the memory mutant dunce. J Neurosci 20 : 2104–2111. 10704484

23. Lee D, O'Dowd DK (1999) Fast excitatory synaptic transmission mediated by nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in Drosophila neurons. J Neurosci 19 : 5311–5321. 10377342

24. Leung HT, Branton WD, Phillips HS, Jan L, Byerly L (1989) Spider toxins selectively block calcium currents in Drosophila. Neuron 3 : 767–772. 2642017

25. Ping Y, Tsunoda S (2011) Inactivity-induced increase in nAChRs upregulates Shal K(+) channels to stabilize synaptic potentials. Nat Neurosci 15 : 90–97. doi: 10.1038/nn.2969 22081160

26. Ping Y, Waro G, Licursi A, Smith S, Vo-Ba DA, et al. (2011) Shal/K(v)4 channels are required for maintaining excitability during repetitive firing and normal locomotion in Drosophila. PLoS One 6: e16043. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016043 21264215

27. Heisenberg M, Borst A, Wagner S, Byers D (1985) Drosophila mushroom body mutants are deficient in olfactory learning. J Neurogenet 2 : 1–30. 4020527

28. McGuire SE, Le PT, Davis RL (2001) The role of Drosophila mushroom body signaling in olfactory memory. Science 293 : 1330–1333. 11397912

29. van Swinderen B (2009) Fly memory: a mushroom body story in parts. Curr Biol 19: R855–857. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.07.064 19788880

30. Tanaka NK, Tanimoto H, Ito K (2008) Neuronal assemblies of the Drosophila mushroom body. J Comp Neurol 508 : 711–755. doi: 10.1002/cne.21692 18395827

31. Tanaka NK, Awasaki T, Shimada T, Ito K (2004) Integration of chemosensory pathways in the Drosophila second-order olfactory centers. Curr Biol 14 : 449–457. 15043809

32. Belote JM, Fortier E (2002) Targeted expression of dominant negative proteasome mutants in Drosophila melanogaster. Genesis 34 : 80–82. 12324954

33. Saville KJ, Belote JM (1993) Identification of an essential gene, l(3)73Ai, with a dominant temperature-sensitive lethal allele, encoding a Drosophila proteasome subunit. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 90 : 8842–8846. 8415617

34. Smyth KA, Belote JM (1999) The dominant temperature-sensitive lethal DTS7 of Drosophila melanogaster encodes an altered 20S proteasome beta-type subunit. Genetics 151 : 211–220. 9872961

35. Madshus IH, Stang E (2009) Internalization and intracellular sorting of the EGF receptor: a model for understanding the mechanisms of receptor trafficking. J Cell Sci 122 : 3433–3439. doi: 10.1242/jcs.050260 19759283

36. Longva KE, Blystad FD, Stang E, Larsen AM, Johannessen LE, et al. (2002) Ubiquitination and proteasomal activity is required for transport of the EGF receptor to inner membranes of multivesicular bodies. J Cell Biol 156 : 843–854. 11864992

37. Balut CM, Gao Y, Murray SA, Thibodeau PH, Devor DC (2010) ESCRT-dependent targeting of plasma membrane localized KCa3.1 to the lysosomes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 299: C1015–1027. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00120.2010 20720181

38. Balut CM, Loch CM, Devor DC (2011) Role of ubiquitylation and USP8-dependent deubiquitylation in the endocytosis and lysosomal targeting of plasma membrane KCa3.1. FASEB J 25 : 3938–3948. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-187005 21828287

39. Hendel T, Michels B, Neuser K, Schipanski A, Kaun K, et al. (2005) The carrot, not the stick: appetitive rather than aversive gustatory stimuli support associative olfactory learning in individually assayed Drosophila larvae. J Comp Physiol A Neuroethol Sens Neural Behav Physiol 191 : 265–279. 15657743

40. White BH, Osterwalder TP, Yoon KS, Joiner WJ, Whim MD, et al. (2001) Targeted attenuation of electrical activity in Drosophila using a genetically modified K(+) channel. Neuron 31 : 699–711. 11567611

41. Benzer S (1967) Behavioral mutants of Drosophila isolated by countercurrent distribution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 58 : 1112–1119. 16578662

42. Xu Y, Condell M, Plesken H, Edelman-Novemsky I, Ma J, et al. (2006) A Drosophila model of Barth syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103 : 11584–11588. 16855048

43. Elliott DA, Brand AH (2008) The GAL4 system: a versatile system for the expression of genes. Methods Mol Biol 420 : 79–95. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-583-1_5 18641942

44. Bakker A, Krauss GL, Albert MS, Speck CL, Jones LR, et al. (2012) Reduction of hippocampal hyperactivity improves cognition in amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Neuron 74 : 467–474. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.03.023 22578498